Executive Summary

Financial advisors have many ways to add value to clients’ investment portfolios, from selecting an appropriate asset allocation to rebalancing when appropriate. However, because the investor ultimately only gets to spend what they can keep after taxes, another important way advisors can add value to a portfolio is to improve its tax efficiency; after all, if the same returns can be generated in a more tax-efficient manner, in the end, investors will generate more spendable wealth (a form of ‘tax alpha’). And when it comes to individual investors and their typical mix of investment accounts and retirement accounts, one of the best ways to enhance portfolio tax efficiency is through strategic asset location, where the advisor places assets into taxable or tax-advantaged accounts depending on the assets’ specific characteristics.

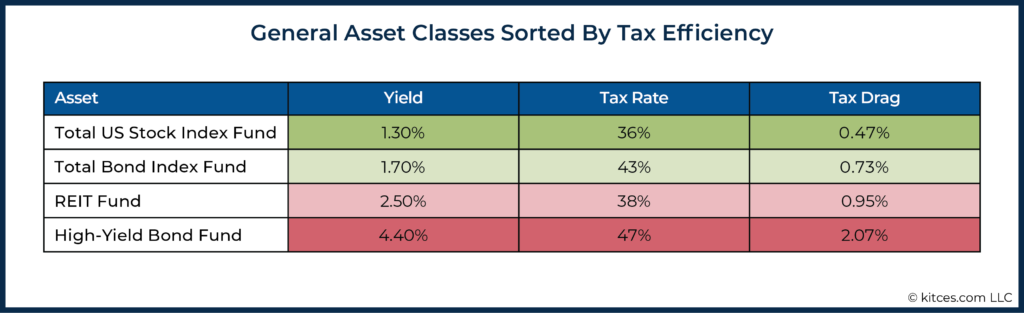

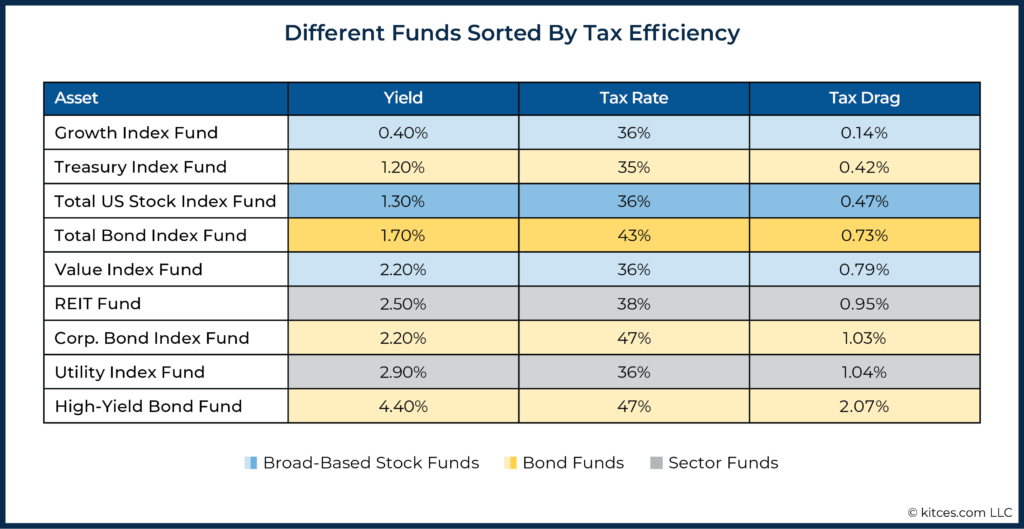

Implementing an asset location strategy begins with identifying the yield, tax rate, and potential tax drag of each investment in an individual’s portfolio. The investments are then sorted into an asset location priority list based largely on tax efficiency, which can be used to help identify where to house each type of investment, with the least tax-efficient holdings being placed into the most tax-advantaged account. Which means a stock fund with a low yield (and low tax drag) might be placed in a taxable account, whereas a high-yield bond fund (with high tax drag) might be placed in a tax-deferred account, thereby reducing the amount of taxable investment income in the current year.

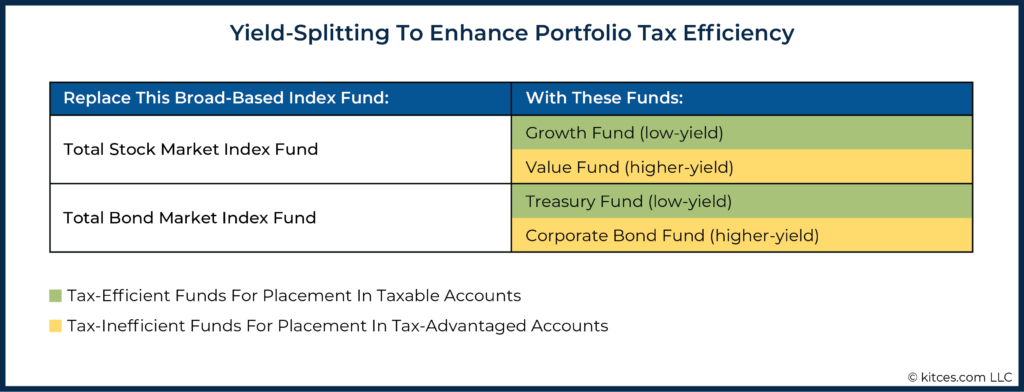

In addition to using asset location to strategically place investments, advisors can further enhance tax efficiency by replacing the use of broad-based index funds with a corresponding pair of funds – one low-yield tax-efficient fund and another higher-yield, tax-inefficient fund. This process, called “yield splitting”, emulates broad-based index funds in such a way that allows for their component (low- and high-yielding) parts to be invested into separate accounts by tax efficiency.

For example, with a yield-split asset location strategy, rather than investing in a single total-stock-market index fund, an advisor would instead invest in both a low-yield growth index fund and a higher-yield value index fund. The intent would be to maintain a similar return overall, but also to allow the advisor to invest the funds separately, placing the higher-yield value fund in a tax-advantaged account and the low-yield growth fund into a taxable account. Similarly, replacing a total-bond-market fund with a high-yield corporate bond fund invested in a tax-deferred or tax-exempt account and a lower-yielding Treasury bond fund invested in a taxable account would potentially reduce the tax drag while maintaining comparable expected returns.

Over time, asset location can reduce the ongoing tax drag of the portfolio by nearly 10 basis points per year (of hard-dollar tax savings!), and layering the yield split methodology on top can double the asset location tax alpha by another 10 basis points (to a total of 20 bps). Cumulatively, this can add up to a 6% increase in long-term wealth accumulation over an investor’s multi-decade time horizon, simply by restructuring (i.e., yield-splitting) their core index holdings into the component parts for better asset location.

Ultimately, the key point is that while asset location is already a beneficial strategy to create tax alpha, the tax efficiency of a portfolio can be further improved upon with a yield-splitting approach to allow for even more-finely-tuned asset location implementation… all while maintaining a substantively identical overall risk/return profile for the portfolio as a whole. This not only leads to potentially significant tax savings for clients – particularly those who have the capacity for both tax-advantaged and taxable account holdings, and who pay a high Federal tax rate (and/or who live in states with high tax rates) – but also provides a tangible way for the advisor to demonstrate their own value!

Tax-Efficient Asset Location Of Funds Can Increase The Tax Efficiency Of Investment Portfolios

One of the most impactful ways an advisor can add value to a client’s portfolio is by increasing its tax efficiency. In the end, investors only get to use the returns that they keep on an after-tax basis, which means two portfolios with the same investment returns may have different financial outcomes based solely on their tax efficiency. This, in turn, creates the potential for a form of ‘tax alpha’ – lifting wealth not by getting better risk-adjusted returns, but through better tax-adjusted returns.

One key component of improving the tax efficiency of an investment portfolio relies on asset location, which refers to the specific account types – taxable, tax-deferred, or tax-exempt – used to hold assets. By creating an asset location strategy that designates the best investments to be held in each of these three account types, advisors can aim to minimize the overall tax drag on the portfolio over a client’s lifetime, potentially capturing significant tax savings without necessarily changing the portfolio’s risk and return characteristics.

And while tax efficiency of portfolio holdings may not be relevant for all investors (as some ultra-high-net-worth individuals may have so little tax-advantaged space that tax-efficient fund placement doesn’t matter, and others may have overall taxable income and tax rates too low for portfolio tax efficiency to be a significant concern), for many, asset location can be critically important and a significant tax-alpha opportunity.

Prioritizing Assets By Tax Efficiency Offers A Framework For Choosing The Right Asset Location

Implementing a tax-efficient fund placement strategy starts by identifying the yield, tax rate, and potential tax drag of each type of investment in an individual’s portfolio. Then, the investments are sorted into an asset location priority list based largely on tax efficiency, which can be used to help identify where to house each type of investment, with the least tax-efficient holdings being placed into the most tax-advantaged account (especially if they otherwise have a strong return potential).

For example, the asset location priority list for an investor with 4 funds is shown below and is based on the investor’s particular tax rate and the yield of each fund. The tax drag assumes that the investor pays 12% state tax, 35% Federal tax with the 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT) on income, and 23.8% Federal tax with NIIT on dividends. Further, it assumes that all dividends are qualified, and that a 20% QBI tax deduction can be taken on REIT distributions. Lastly, 40% of the investor’s portfolio is taxable, the rest is tax exempt. The tables are sorted from top to bottom by tax efficiency.

Nerd Note:

The data tables used throughout this article are for demonstration purposes only, but all data for index funds reflect late-2021 SEC yields from Vanguard and iShares ETFs. They also assume that Treasury bonds and the Treasury-bond portion of total bond funds (roughly a third of interest) are exempt from state tax.

For the investor with the portfolio above, the less tax-efficient funds would be allocated to a tax-advantaged account from the bottom up, until the tax-advantaged space is full. Note that tax efficiency and tax drag are investor-specific, since different investors will have different tax rates (even when they otherwise have the same investment holdings).

While nothing in the tax-efficient-fund-placement discussion above is novel, it is interesting to refresh the data on tax efficiency for different funds. Even with the relatively low yields of late 2021, a high-yield bond fund with a yield of 4.4% has nearly 5 times the tax drag of a stock index fund yielding 1.30%. In addition, asset-location priority lists can – and do! – shift over time and geography. For example, an investor who holds primarily European sovereign bonds and European stocks would almost certainly hold the bonds in a taxable account (since they have yields very near 0%, much lower than stocks with yields closer to 2%).

How A Yield-Split Approach Can Enhance The Tax Efficiency Of Asset Location

Some investors choose to allocate a substantial portion of assets in broad-based index funds as part of a core-plus-satellite strategy, three-fund portfolio, or another model strategy. For these investors, using a strategy that replaces single broad-based index funds by using a pair of funds – one low-yield (tax-efficient) and another high-yield (tax-inefficient) – allows for the tax-inefficient portion to be placed in a tax-advantaged account, while the tax-efficient portion remains in a taxable account. This results in better after-tax performance through increased tax efficiency, without changing the fundamental composition of the portfolio itself.

Specifically, a total-stock-market index fund would be replaced with a value fund and a growth fund, and a total-bond-market index fund with a Treasury fund and a corporate bond fund. This ‘yield-split’ strategy is consistent with existing advice on tax-efficient fund placement, but it also gives advisors more flexibility in which funds to allocate to which account.

In practice, by splitting broad-based index funds into the underlying components, the resulting portfolio building blocks will have some funds with an even-lower yield than the broad-based index, and others will have a much-higher yield. The blended rate would still produce a similar return to the original total-market index, but by owning the individual components, it’s feasible to asset-locate more efficiently.

To illustrate how a yield-split strategy can offer substantial savings in annual tax drag, consider the following example for a hypothetical investor with a portfolio solely consisting of a total-stock-market index fund.

Example 1: Alice is an investor with a $1 million portfolio, of which $500,000 is in a tax-advantaged account, and the other $500,000 is in a taxable account.

Her tax rates are as follows:

- 32% Federal tax on income

- 20% Federal tax on qualified dividends

- 12% state tax on dividends and interest.

- 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT)

Alice’s portfolio is fully allocated to a total stock market index. With no tax-efficient fund placement, she holds this same total-stock-market index fund in both taxable and tax-advantaged accounts.

In October 2021, the total stock market index was yielding about 1.3%. Thus, Alice’s annual taxes are $500,000 (taxable account balance) × 1.3% (yield on the total stock market index) × 35.8% (combined Federal and State tax on dividend income, and NIIT) = $2,327 in annual taxes.

However, Alice’s financial advisor, Mel, suggests using a yield-split strategy to improve the tax efficiency of Alice’s portfolio. Accordingly, Mel advised Alice to hold $500,000 in a growth index fund (yielding 0.4%) placed in her taxable account, and $500,000 in a value index fund (yielding 2.20%) placed in her tax-advantaged account.

By implementing this strategy, Alice’s annual tax bill dropped to $500,000 (taxable account balance) × 0.4% (yield on the growth index fund) × 35.8% (tax rate) = $716, a more-than-two-thirds reduction in annual tax liability, despite having a portfolio with the same risk and expected return characteristics!

Another example illustrates how using a yield-split strategy can benefit a portfolio fully allocated to a bond market index. While bond interest is generally taxed as normal income, Treasury bond interest is exempt from state tax. Which means that, for investors in a high state-income-tax bracket, it’s especially advantageous to have Treasury bonds in a taxable account relative to corporate bonds.

Example 2: Like Alice in Example 1, above, Bob is an investor with a $1 million portfolio, in which $500,000 is in a tax-advantaged account, and the other $500,000 in a taxable account.

Bob’s tax rates are as follows:

- 32% Federal tax on income

- 20% Federal tax on qualified dividends

- 12% state tax on dividends and interest

- 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT)

Bob’s portfolio is fully allocated to a total bond market index. With no tax-efficient fund placement, he holds this total-bond-market index fund in both taxable and tax-advantaged accounts.

In late 2021, the total bond market index was yielding about 1.7%. Assuming that roughly 1/3 of the income from the total bond fund is from government obligations exempt from state tax, we can estimate that the approximate tax drag of the portfolio is $500,000 (taxable account balance) × 1.7% (bond market index yield) × [ ⅓ × 35.8% (Fed income tax + NIIT) + ⅔ × 47.8% (Fed and state tax + NIIT)] = $3,723.

Bob sees Mel, the same financial advisor as Alice, and as with Alice, Mel suggests using a yield-split strategy to improve the tax efficiency of Bob’s portfolio. Accordingly, Mel advises Bob to hold $500,000 in a Treasury bond index fund (with a yield of about 1.2%) placed in his taxable account, and $500,000 in a corporate bond index fund (with a yield of about 2.2%) placed in his tax-advantaged account.

By implementing this strategy, Bob’s annual tax bill dropped to $500,000 (taxable account balance) × 1.2% (yield on the Treasury bond fund) × 35.8% (state-tax exempt tax rate) = $2,148, a 42% reduction in annual tax drag, despite having a portfolio with similar risk and expected return characteristics!

While few advisors’ clients would be invested in a single fund, as in these examples, the scenarios above simply serve to generalize the idea well. Now let’s consider the following example, which offers a more realistic scenario showing the benefits of tax-efficient fund placement with, and without, the yield split strategy.

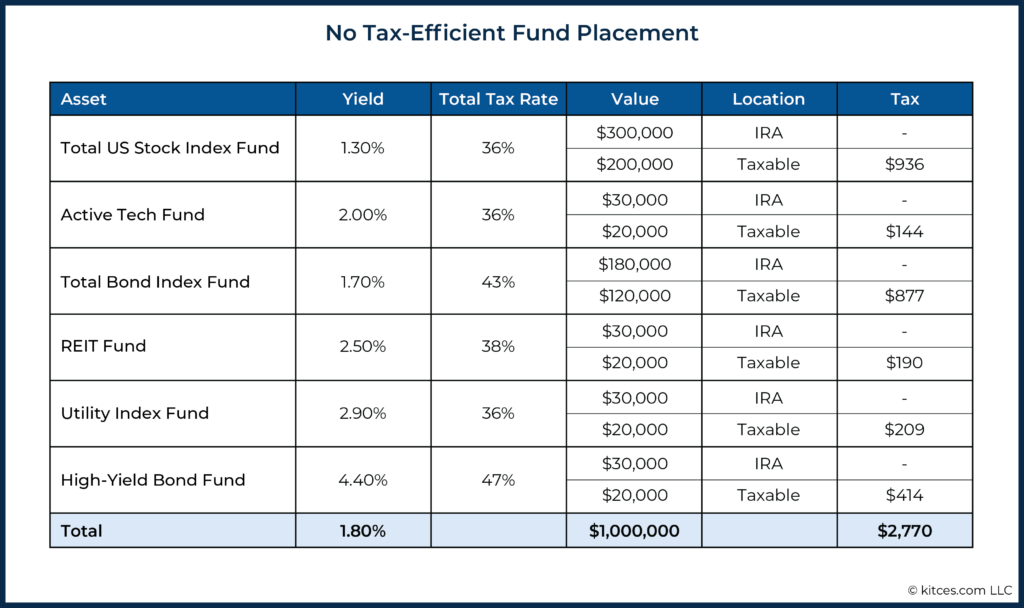

In the examples below, the investor has a more complex portfolio constructed using a core-satellite investing strategy, with the ‘core’ portion of the portfolio invested in the US stock and total bond markets, and the ‘satellite’ portion consisting of some sector funds and other actively managed investments.

Example 3: Charlotte is an investor with a core-satellite portfolio, with 40% invested in a taxable brokerage account and 60% invested in a tax-advantaged account.

Her investments consist of the following:

- 80% core allocation: total US stock market and total bond market

- 20% satellite allocation: REITs, high-yield bonds, utilities, and a low-turnover active growth fund

With this allocation, her annual tax drag will be $2,770 on her $1M portfolio, or roughly 28 basis points.

The example above illustrates Charlotte’s portfolio with no consideration given to asset location. But by manipulating the placement of her existing funds with the aim of increasing tax efficiency, Charlotte can reduce her tax drag considerably.

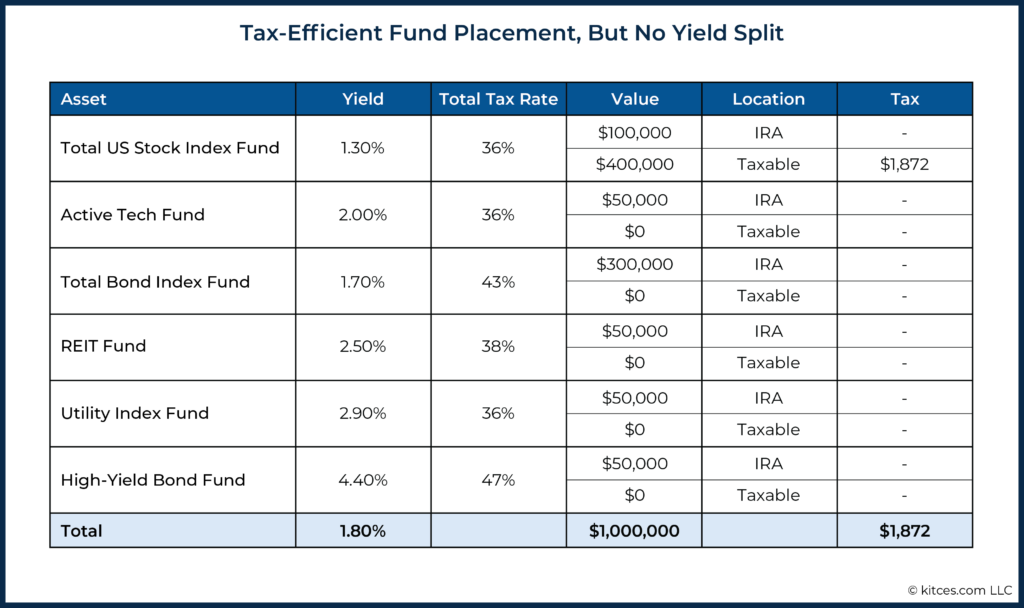

Example 4: Reviewing the original data from her portfolio (see Example 3), Charlotte thinks she can do better with some simple asset location adjustments. She adjusts her portfolio so that 80% of her Total US Stock Index (which makes up half of her total holdings) is the only asset in her taxable account. The remainder of her assets are located into her Traditional IRA.

This way, her taxable account still comprises 40% of her total allocation, but now holds only her most tax-efficient holding. By doing this, the total tax drag of the portfolio results from the portion of Total US Stock Index held in the taxable account; which means that the total tax drag of the portfolio is $1,872, or roughly 1.3% (yield) × 36% (tax rate) × 40% (taxable account allocation) =19 basis points on her $1M portfolio.

The example above shows how asset location alone, with no modification of the actual portfolio assets, can impact the overall tax drag by relocating the most tax-efficient funds into taxable accounts, and the less tax-efficient funds into tax-advantaged accounts.

However, using a yield-split strategy lets the investor further refine how assets can be prioritized by tax efficiency, without changing the overall nature of the underlying investments.

Example 5: After designing a new asset location strategy for her portfolio, Charlotte decides to review her proposed portfolio adjustments with Wilbur, her financial advisor.

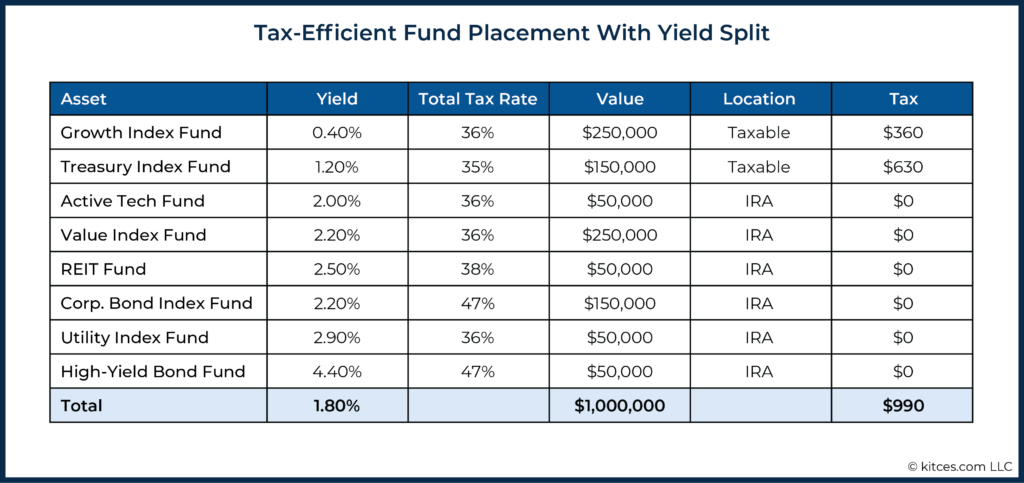

Wilbur reviews Charlotte’s proposed changes and thinks that she can do even better if she were to use a yield-split strategy. Accordingly, he suggests that Charlotte make the following changes:

- Replace the Total US Stock Index with value and growth funds

- Replace the Total Bond Index with corporate and treasury funds.

After prioritizing her new portfolio holdings by tax efficiency and placing funds into accounts using the yield-split strategy recommended by Wilbur, and illustrated in the chart below, Charlotte now realizes a tax drag of only $990, or roughly 10 basis points!

Nerd Note:

While a total bond market index fund also has mortgage-backed securities, these are ignored for the sake of simplicity in this example. The risk-return characteristics of a portfolio of half treasuries and half corporate bonds are very close to a total-bond index fund.

In the example above, Charlotte used a yield-split strategy to achieve tax savings of roughly 20 basis points annually for an investor paying a high, but not maximal, tax rate. Roughly 10 basis points of this savings come from standard tax-efficient fund placement, as illustrated in Example 4, and another 10 bps comes from using the yield-split strategy as shown in Example 5: replacing the stock index fund with value and growth, and bond index fund with treasuries and corporates.

The idea of yield-splitting follows the same tax-efficient advice of asset location, but by splitting up broad-based index funds into component parts of varying levels of tax efficiency, we have more flexibility in placing only the most tax-efficient assets in our limited taxable space.

How Much Does Tax-Efficient Fund Placement Matter?

To give the impact of yield-splitting some long-term context, consider a portfolio that is compounded for 35 years. A 20-basis-point drag would cost about 6% in terminal portfolio value, so ‘finding’ 20 basis points of annual savings over 35 years would be roughly equivalent to adding around 6% to the portfolio’s long-term cumulative value.

Even for investors who are deferring taxes (e.g., via a Traditional IRA) rather than eliminating them (e.g., through a Roth IRA), the yield-split strategy will often reduce regular annual taxes during their working years and instead give rise to unrealized capital gains during their retirement years. These gains can be realized at a time of the advisor’s choosing (tactically harvesting capital gains at lower or even 0% tax rates), and can also potentially be eliminated altogether for assets passed to heirs at death.

In general, tax efficiency can matter a lot, especially for those investors who have a rough balance between tax-advantaged and taxable space, who pay a high tax rate, and for investors in states with high tax rates.

What happens if the level of yields changes? The data for this article was taken in late 2021, and in the span of a few months since then, yields have risen dramatically, which increases the overall amount of tax drag that can benefit from good asset location. With respect to the yield split strategy in particular, though, the tax savings that can be achieved are primarily related to the difference in yields between funds, not the absolute level of yields. So even if yields change substantially throughout an investor’s lifetime, tax-efficient fund placement (and yield-split of broad-based indices) will continue to be important.

Implementation Of The Yield-Split Strategy

The explosive growth of index funds and ETFs over the last few decades has given advisors the tools to access increasingly finely sliced segments of the markets for an extremely low cost. This expansion in the breadth of available funds is especially helpful to implement the yield-split strategy, as it is the ability to build portfolios from the components of broad-based market indices that allows for improvements in tax-efficient fund placement by replacing a single broad-based fund with two (or even more) constituent funds with different levels of tax efficiency.

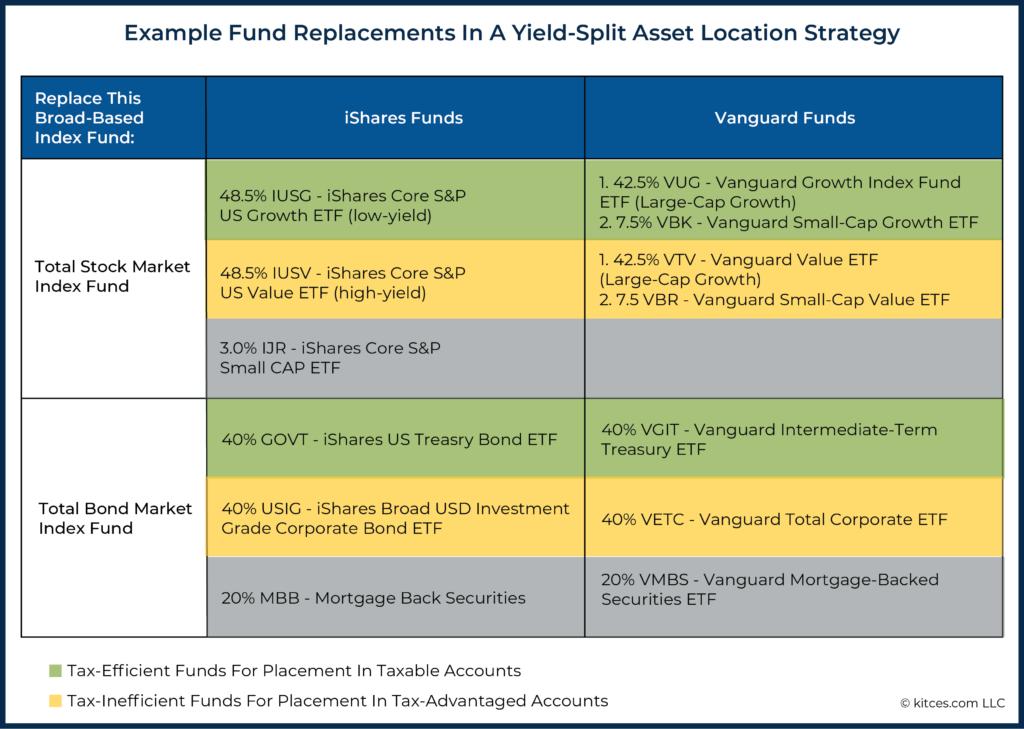

When it comes to potential fund choices to implement the yield-split strategy, advisors have many options. While most stock fund families are typically structured such that there isn’t often a single pair of value/growth funds that perfectly replicates the total market, the most straightforward example of replacing a total stock market index fund would involve iShares ETFs, replacing a total market ETF with 50% IUSV (iShares Core S&P US Value ETF) and 50% IUSG (iShares Core S&P US Growth ETF).

These two value/growth ETFs have large- and mid-cap stocks, but not small-cap, so if we wanted to be a bit more precise, we’d replace the total market with 48.5% IUSV, 48.5% IUSG, and the remaining 3% IJR (iShares Core US S&P Small Cap ETF). Because the position in the small-cap ETF is so small, whether it’s in a taxable or tax-advantaged account doesn’t have a substantial impact (as the tax drag on ‘just’ a 3% total allocation is very small relative to the overall portfolio). With or without the small-cap ETF addition, both portfolios have a correlation to the US total market that rounds to 1.00, and very similar performance.

With Vanguard, precise replication of the total market fund is possible, but requires 4 different ETFs covering small- and large-cap value and growth as indicated in the table below. An advantage of the Vanguard fund family is that it allows a yield-split strategy within a market-cap segment.

For example, if an advisor has a portion of a client’s assets allocation specifically to Vanguard’s large-cap fund, that can be replaced in a yield-split strategy with large-cap value (VTV) and large-cap growth (VUG).

For bonds, a yield-split strategy can be implemented by replacing a total bond market fund with a corporate bond fund (for tax-advantaged accounts) and a Treasury fund (for taxable accounts). A simple example would be to use a 50% USIG (iShares Broad USD Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF) and 50% GOVT (iShares US Treasury Bond ETF) allocation to approximate the total bond market. If we wanted to be more precise, we could reduce USIG and GOVT to 40% and add 20% MBB (Mortgage-backed securities), which are in most total bond market indices.

Unlike with stocks, there is a fair bit of variability over what’s included in the total bond market index… performance differences among three of the larger total bond market ETFs (Vanguard’s BND, iShares IUSB, and Schwab’s SCHZ) are far larger than among total stock ETFs (Vanguard VTI, iShares ITOT, and Schwab’s SCHB). So with bonds, identifying the ‘correct’ basket to track will be more specific to the particular total market bond fund (or underlying bond index) the advisor uses, though given the limited variability of bonds overall, half treasuries and half corporates remains a remarkably close (and thus appealing) simplification.

Ultimately, the key point is that tax-efficient asset location continues to be important even in today’s lower-yielding environment, especially for investors in high-tax states. Advisors can turbocharge their clients’ tax savings by splitting a single broad-based index fund into two (or even more) component index funds with different levels of tax efficiency, specifically to be able to locate the less-tax-efficient component in a tax-advantaged account.

Implementing these strategies can save investors in high-tax states 15 basis points or more in annual tax drag, without changing the risk/return composition of their portfolios, which, over a 35-year horizon, can lead to a final portfolio value that is 6% higher than if yield-splitting were not implemented!

The information on Vanguard’s ETFs is wrong. Vanguard’s large and small complement each other to mirror the total market. Vanguard’s large is then divided into mega-cap and mid-cap components. To my knowledge, Vanguard is the only provider for whom mid-cap is not a necessary element between large and small. This information is evident from the CRSP index methodology paper and used to be included in a helpful graphic on Vanguard’s website.

Further, it would seem Vanguard’s large value and growth ETFs would be better candidates for this strategy since the SEC yield on the Vanguard growth fund is .46% while the iShares S&P 900 growth fund’s SEC yield is 0.7%.

Thanks for the feedback…we’ll take a look at the CRSP methodology and holdings data of the vanguard ETFs and update to remove mid-cap if appropriate.

I agree that the yield spread between vanguard large-cap value and growth makes those two ETFs very attractive candidates. Late last year when I was first looking at this, there were time when the growth ETF yield was below 0.4%!

Please correct me if I am missing something… While this strategy makes sense, I see several potential issues with implementing it:

1) In a rising market how do you shift asset allocation across taxable accounts without incurring significant capital gains?

2) Different stages of life often bring different needs for income and different tax consequences. An allocation at 30 may no longer be effective at 65 and beyond if/when IRMAA, RMDs, QCDs, and other factors kick in.

3) Yield curves may change over time which can lead to trade-offs in which types and duration of bonds are favored – corporate, municipal, etc.

4) Other life changes – getting married, losing a job, etc. also impact income needs and allocation.

In these situations it may be difficult to shift asset locations without incurring significant capital gains in taxable accounts. Many of these situations are unpredictable and not under the control of the investor.

How do you factor in the cost of shifting asset locations (e.g. capital gains) as conditions change?

You raised a very good point about rebalances and changing asset allocations. I think it’s relevant for any investor with a tax-aware asset location strategy: not just the yield split. The simplest example: an investor with stocks in taxable and bonds in an IRA may have to rebalance and trigger sale of an appreciated asset. I put a few thoughts below about avoiding the realization of taxable gains, with the yield split or any tax-aware asset location strategy, which are relevant to your points 1, 3, and 4:

1. Investing dividends received and new contributions in the under-weight fund can help limit the need to sell appreciated assets. Even without a yield split strategy, this can help investors deal with rebalances and appreciated assets in taxable accounts.

2. Any asset location strategy doesn’t have to be applied to 100% of the portfolio. Again, take the simple example of the investor for whom it’s best to have stocks in a taxable account and bonds in tax-deferred. Instead, this investor could be 80/20 stocks/bonds in taxable, 20/80 stocks/bonds in tax deferred, and use the tax-deferred account to sell appreciated stocks if a rebalance is triggered in a year with a large market move. This, in combination with re-directing dividends/contributions to the under-weight asset should limit the need to realize taxable gains.

3. The bond side of the yield split, preferring treasury bonds in a taxable account, generally won’t trigger large capital gains relative to annual income, and also takes advantage of the state-tax exemption of treasury bonds.

None of the above guarantee you’ll never have to realize a taxable gain, but they help minimize it.

Your point about managing the duration and composition of an investor’s bond allocation (#3) is interesting and quite relevant with rising rates. Re-adjusting a bond allocation could lead to taxable gains, though likely far far smaller gains than with stocks. As above, this challenge of avoiding realized gains in bonds occurs any time you hold bonds in a taxable account, and isn’t limited to a yield-split type strategy.

One possibility is to further divide the bond universe by duration (long/medium/short) as well as issues type (treasury/corporate), and prefer shorter and medium-term treasury funds in taxable, and longer-term treasuries and corporate funds in tax advantaged. The shorter-term funds will be even lower yield and have negligible gains. This would be a more advanced version of using multiple constituents gives an advisor more flexibility in tax optimization.

Thanks Chris for sharing this valuable information to us.

I’m sorry, but I got lost right from the start. By the word ‘yield’ are you really ignoring capital gains completely? But the benefits from tax-sheltering compound over time at the asset’s total rate of return (including cap gains). Even when it is assumed cap gains are 0% taxed (as in the example shown in this image where stocks earn 8%, taxed at 3.75% (15% tax on 2% dividends; 0% taxed capital gain), and bonds earn 3% and are taxed at 25%, it is the total return that determines the slope of the accumulating tax-sheltering benefits. You can check the math creating that chart at https://www.retailinvestor.org/ods/USspreadsheets.xlsx on Tab (f)

https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/220e8ab055a842ee3ba7d06782a552e6ca688440e7b86198acc0be29002fe9b8.png

And there is your starting point using ‘tax efficiency’ metrics. Those are also calculated on the spreadsheet linked, for any input assumptions. You can see they show that ‘tax efficiency’ conclusions are only valid for 1 year time spans. While the article you linked does recognize that rates of return will change the location advice, it was already established at that time (https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2317970) that it is the Time factor that determines the Location conclusion. And the tax efficiency metric has no variable for Time.

Thank you for your feedback. The idea here isn’t to identify a new method for asset location strategies…there’s already been a lot of work on that (see the notes below). Rather, the idea is you can take an existing set of funds, and by splitting broad-based funds into components, you get more choices in your asset location decision. The two simple examples presented (value vs. growth stocks and treasury vs. corporate bonds) were intended to be instances where the ‘split’ components have similar long-term growth rates, meaning the one-period effect dominates. When making decisions between funds with massively different long-term growth rates, link bonds vs. stocks, I 100% agree that the difference in growth rates becomes important.

Prior Work:

I’m interested in reading the article you referenced, but the link you posted doesn’t work for me…it goes to a 404.

This article cites Kitces prior work, which is linked below

https://www.kitces.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Kitces-Report-January-February-2014-Exploring-The-Benefits-Of-Asset-Location.pdf

Again, to summarize, the idea isn’t to throw out existing work on asset location…rather, it’s to point out that splitting up single broad-based funds into smaller components gives you more options when making asset location decisions using your existing framework, and the simpler examples

presented are intended to be among assets with similar growth rates.

Interesting piece. Thanks for sharing. I have a couple quick questions…

1. Is the 8% NIIT in the examples a typo? Should that be 3.8%?

2. Do you have (or does anyone have) a general % of annual tax drag that can be assigned to a “typical” investment portfolio? I realize each will generate their own unique amount of taxes but just wondering if there is a general range or approximated midpoint.

3. Why not simply utilize an insurance wrapper for the taxable portion? For ~70 bps per year, both dividend/interest and cap gains taxes can be eliminated. Recent IRC 7702 regs lower charges and making wrappers less expensive.

Hi James!

Regarding the first point – that indeed was a typo. We corrected it – great catch!

Thanks for the feedback James. For point 2, average tax drag, it’s a good question…I haven’t seen any previous work on this, but I’ll look around on this over the next few days. This probably would vary with market yields. For point 3, this sounds very interesting…do you have any more details on this? I’ll take a look and get back to you.

Generally speaking, the tax drag on a S&P 500 ETF will only be around 25-50 bps, but it varies. For example, with a yield around 1.2% at a QDLTCG rate of .15 plus an average state income tax rate of .04, you get an annual drag of 22.8 bps. With a yield around 1.2% at a QDLTCG rate of .20 plus NIIT of .038 and state income tax rate of .093, the drag would be 39.72 bps. Figuring out the tax drag for a bond allocation is more complex since there are more safety valves like municipal bonds and putting the bond allocation in a traditional IRA. Nevertheless, for a total bond fund yielding 2.2% in a taxable account with a marginal rate of .22 and a state income tax rate of .04, the drag would be 57 bps. It’s starting at a much worse level than the stock asset.

I have no problems with an insurance wrapper of some kind for the bond allocation. But it’s more problematic for the stock assets because it will transform the ultimate QDLTCG treatment of returns into ordinary income. Further, it will be more difficult to hold the policy until death in a cost-efficient manner due to higher COI drag in the later years. Last, it’s not clear that the potential savings are very much except in really corner situations like California residents in the highest tax brackets.