Executive Summary

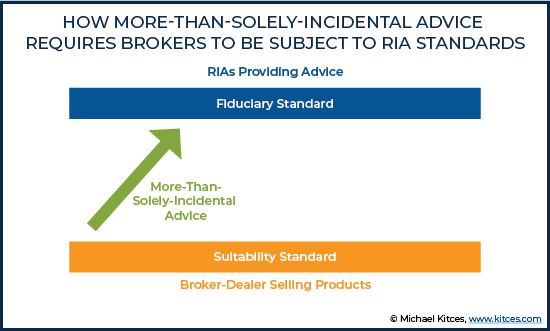

Since the beginning of the modern era of financial services regulation in the aftermath of the crash of 1929 and the Great Depression, Congress has recognized a fundamental difference between the activities of broker-dealers and registered investment advisers. Broker-dealers were in the business of literally brokering (effecting securities transactions for their customers) and dealing (effecting securities transactions for their own accounts) as a part of the capital formation process and operation of publicly traded investment markets. While registered investment advisers were in the business of providing advice itself. And accordingly, the two were assigned different regulatory standards, with a Suitability standard for sales-based, transactional brokerage activity, and a Fiduciary standard for advice.

Yet in recent decades, the rise of technology has made various brokerage services increasingly accessible to consumers directly (through the discount brokerage movement and then the emergence of online brokers), coupled with the emergence of the independent broker-dealer model (independent of the investment banks that used to own broker-dealers to facilitate the sale and distribution of public offerings they underwrote), has increasingly led broker-dealers in the direction of providing advice to supplement (or validate entirely) their value proposition to their customers. Leading to a blurring of the lines between broker-dealers and investment advisers, and leading Congress in enacting the 2010 Dodd-Frank legislation to direct the SEC to lift the standard of conduct for brokers to be at least as stringent as the standard for RIAs, recognizing the advice that broker-dealers now deliver.

However, in issuing the new Regulation Best Interest rules, the SEC declined to equalize the standard of care for broker-dealer-delivered versus RIA-delivered advice as mandated by Dodd-Frank, and instead expanded the broker-dealer exemption that would allow broker-dealers to even more easily provide comprehensive financial planning advice without being subject to a fiduciary standard for that advice, nor for the implementation of that advice, and without requiring such advisors to register as investment advisers either… which creates, literally, a double-standard for the delivery of financial planning advice.

Accordingly, last week XY Planning Network filed suit against the SEC to challenge Regulation Best Interest, recognizing that the SEC both failed to follow the provisions of Dodd-Frank to apply an advice standard for brokers at least as stringent as the RIA standard, and that the SEC has exceeded its authority by impermissibly trying to re-write the registration requirements to become an investment adviser to stipulate that investment advisers are only engaged in such fiduciary activity when they manage investment accounts and not with respect to the entire advisor-client relationship (even contradicting SEC’s own prior and concurrent guidance). Particularly when it comes to the delivery of comprehensive financial planning, which the SEC itself recognized in 2005 as being too comprehensive by its nature to be considered “solely incidental” to the sale of brokerage products, and instead would have required all financial planning to be delivered under the aegis of an RIA (before the 2005 rule itself was vacated in FPA vs SEC).

Ultimately, though, the purpose of the XYPN lawsuit against the SEC is not to undermine the ability of broker-dealers to engage as such; instead, the issue is simply that Congress has repeatedly prescribed that the delivery of financial advice must be delivered under a fiduciary standard of care, either by lifting the standards for brokers when providing such advice, or by requiring such advice to be delivered as a registered investment adviser in the first place. In other words, the point is not to challenge the broker-dealer model, but simply to separate brokerage sales from investment advice – as Congress mandated nearly 80 years ago – and instead let financial advisors be (fiduciary) advisors, and let brokers be brokers (who market and communicate their services as such to the public). Especially when delivering comprehensive financial planning, which by its very nature, is too holistic of an advice process to ever be solely incidental to the sale of brokerage products, and must instead be regulated the way all advice has ever been regulated: as fiduciary advice.

Why Broker-Dealers Have A Different (Lower) Standard Than RIAs

The marketplace of publicly traded stocks and bonds is a major driver of the capital formation process for businesses. When a large company wants to raise debt or equity capital – more than what they can raise from private investors they have direct connections with – access to the public markets makes it feasible to execute by taking on very small investments from a large number of public investors. Thus, for instance, a company that wants to raise $1B in capital doesn’t have to find one or several private investors or funds willing to invest $1B; instead, it can sell shares of its equity for $20 each, and if 100,000 investors each buy 500 shares, the company has raised $1B of capital.

The caveat, however, is that most companies don’t know 100,000 individual investors to whom they can solicit capital in exchange for their shares of equity. Instead, companies rely on investment banks to facilitate the process of underwriting that Initial Public Offering of shares. Which may then try to find investors to purchase those shares directly, or employ their subsidiary Dealers to buy most or all of the 50M shares and then attempt to re-sell them to investors to get them into the hands of the public.

Of course, the caveat is that investors don’t necessarily want to buy those shares, if they can’t re-sell them to harvest the value of that investment. Accordingly, investors also rely on Brokers, whose job is to facilitate (i.e., to “broker”) trades of existing securities for their customers.

In other words, a broker-dealer – which effects securities trades both on behalf of its customers (as a Broker), and also for its own account (as a Dealer) – is an essential component of publicly traded markets and the capital formation process, as recognized and formalized under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 that established the ‘modern’ regulatory structure for broker-dealers.

And notably, the business of broker-dealers is a fundamentally sales-oriented transactional business, as the job of broker-dealers, and the stockbrokers they employ, is literally to facilitate the purchase and sale of investments (for themselves or their customers), for which they are paid a commission or mark-up for effecting the transaction. Accordingly, broker-dealers are subjected to a “suitability” standard – that in the process of selling securities to and on behalf of their customers, they only make recommendations that are not unsuitable for that customer.

By contrast, the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 defines a Registered Investment Adviser (RIA) as “any person who, for compensation, engages in the business of advising others”. And under Section 206 of the Act have a stringent requirement not to engage in “any device, scheme, or artifice to defraud any client or prospective client”, which in the case of SEC vs Capital Gains Research Bureau was recognized as necessitating a full-fledged fiduciary duty to RIA’s clients, given the relationship of “trust and confidence” that exists between a client and his/her advisor.

Which means broker-dealers and RIAs have historically had different regulatory standards, because they were engaged in fundamentally different lines of business. Broker-dealers sold stocks and bonds to their customers (either as a broker or as a dealer) and in subsequent decades mutual funds as well, for which they were paid a commission for effecting those transactions, while investment advisers were in the business of providing advice, for which they were paid a fee for that advice.

The caveat, of course, in that ‘touting’ investments that they have for sale, a broker-dealer may unwittingly “recommend” an investment pursuant to the sales process – an implicit form of advice – for which Congress provided an exception that broker-dealers would not be deemed to be giving advice if their advice was “solely incidental to the conduct of his business as a broker or dealer and who receives no special compensation therefor” under Section 202(a)(11)(C) of the Investment Advisers Act.

In other words, Congress in the Investment Advisers Act effectively stated that brokering and dealers can retain its sales-based suitability standard when engaging in the business of being a broker-dealer, but if brokers give advice – anything that is more than “solely incidental” to the product sale – the broker must lift up to register as an investment adviser, and be subject to the investment adviser (fiduciary) standard.

The key question, then, is what arises to the level of advice that is more than “solely incidental”, such that a broker is no longer in the business of being a broker but instead is acting as an advisor. And more generally, about where the dividing line is between sales and advice.

Accordingly, the financial product manufacturing and distribution industry (annuity companies, asset managers, and broker-dealers) prevailed against the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule largely by convincing the courts that brokers and insurance agents weren’t actually in the business of advice, stating variously that “an agent who receives a commission on the sale of a product is not paid for render[ing] investment advice… She is paid for effecting the sale” and that the Department of Labor “failed to identify substantial evidence that sales of these [annuity] products actually take place in such [trusted advice] relationships.” In other words, the product industry successfully made the case that its brokers and insurance/annuity agents aren’t actually financial advisors.

In fact, arguably the entire crux of various fiduciary rules that have been proposed, implemented, and challenged in court over the past two decades, including the SEC’s 2005 broker-dealer exemption for offering fee-based wrap accounts without registering as an investment advisor (vacated in FPA vs SEC in 2007), and the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule requiring brokers to adhere to a fiduciary duty (vacated in Chamber of Commerce, FSI, and SIFMA vs Department of Labor in 2018) all revolved around where to set the line between brokerage sales and investment advice.

Which isn’t entirely surprising, as the “Great Convergence” of broker-dealers and RIAs, driven by technology making securities products increasingly available to consumers directly through technology and driving the human brokers themselves to add value through financial advice, has reached the point today where a consumer may pay 1%/year for ongoing financial advice, and hardly makes a distinction between whether it’s a 1%/year advisory fee, a 1%/year fee-based wrap account, or a 1%/year C-share mutual fund trail. Despite the fact those broker-dealer-based 1%/year commissions were never intended to be for advice in the first place!

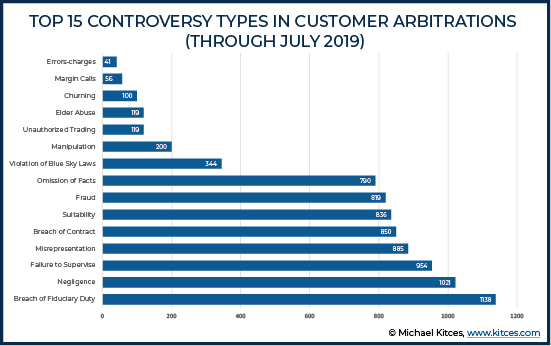

Consequently, in the modern marketplace, the line between fiduciary advice RIAs and sales-based brokers has so blurred that a review by the Consumer Federation of America of 25 leading broker-dealers and insurance companies found all of them to be holding out to the public as being in the business of advice (and not product sales as they stipulated in the Department of Labor court case), and despite the fact that brokers are supposed to be in the business of product sales and not fiduciary advice, the #1 arbitration claim against brokers is a “breach of fiduciary duty” against the advice that brokerage firms claim they’re not giving in the first place.

How Regulation Best Interest Violates Congress’ RIA Registration Requirements For Financial Planning

The increasingly heavy overlap between broker-dealers and investment advisers in the delivery of advice – what is in essence a lax enforcement by the SEC of the “solely incidental” standard that determines when brokers have to switch over to becoming investment advisers – has led to a rising volume of fiduciary regulation over the past decade, all driven around the idea that at a minimum, if broker-dealers are going to provide advice similar to RIAs, they should be held to a similar standard.

Accordingly, when Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in 2010, it stated in Section 913(g) that the SEC would have authority to promulgate rules that when broker-dealers “provide personalized investment advice about securities to a retail customer… the standard of conduct for such broker or dealer with respect to such customer shall be the same as the standard of conduct applicable to an investment adviser…” (emphasis mine) In other words, if brokers are going to give RIA-like advice, and not become registered as investment advisers in the first place, then Congress stated that they should become subject to RIA-like standards of conduct anyway.

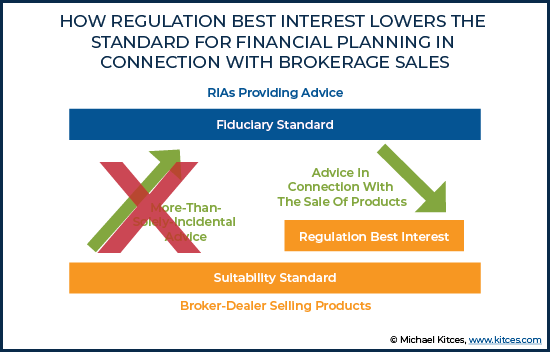

Yet in practice, when the SEC finalized Regulation Best Interest, it chose not to enact the full Dodd-Frank Section 913(g) ‘at least as stringent’ standard for brokers providing advice. And at the same time, chose to re-define the dividing line for what constitutes “solely incidental” advice to be formally defined as advice that is “in connection with and reasonably related to” a broker’s sale of products… which in reality, is in contradiction to the plain language of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 itself.

For instance, consider Jenny, who is new to the financial services industry, has obtained her CFP certification, and has decided that she would like to create and deliver comprehensive financial plans to her clients for a fee. In order to hold out as providing financial planning services – which on a comprehensive basis will clearly include at least some investment advice for which she will be compensated – Jenny must register as an investment adviser, and be subject to a fiduciary duty with respect to her financial planning advice and recommendations.

By contrast, consider Andrew, who has also obtained his CFP certification, wants to create and deliver financial plans to his clients, but chooses instead to be compensated via the implementation of his financial planning recommendations (i.e., commissions on the sale of products to implement the plan), and consequently joins a broker-dealer. Andrew is still in the business of providing comprehensive financial planning advice for compensation, but because his advice recommendations will be implemented “in connection with” the sale of brokerage products, he is not required to register as an investment adviser, and instead is eligible for the lower Regulation Best Interest standard instead. And even if Andrew were dual-registered, the SEC’s Regulation Best Interest stipulates that his investment adviser registration (and thus his fiduciary duty) would apply only to any managed account for which he receives an advisory fee, but not to the act of creating and delivering a comprehensive financial plan (and all the advice it entails) itself and being compensated for that financial planning advice.

In other words, Jenny and Andrew can provide a literally identical comprehensive financial plan to the client, provide the same comprehensive financial planning advice to their clients, and be compensated for it… for which Jenny must register as a fiduciary investment adviser, but because Andrew works for and delivers his financial planning advice in connection with a broker-dealer, he is eligible for the lower Regulation Best Interest standard.

Which means that while the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 requires that brokers who deliver more-than-solely-incidental advice to register as investment advisers and be elevated to the higher standard, Regulation Best Interest instead permits any otherwise-RIA-required advice connected to the sale of brokerage products to be brought down to the lower standard instead. Directly contradicting the purpose and clear language of the Investment Advisers Act itself!

In addition, the SEC also effectively positions RIAs in Regulation Best Interest as providing ongoing advice and investment management services, implying that more “transactional” advice is the domain of broker-dealers. In fact, in the original version of Regulation Best Interest, the SEC repeatedly referred to broker-dealers as the deliverers of “episodic” or “transactional” advice.

Yet in practice, the simplest and most straightforward version of “transactional” advice – financial advice delivered for an hourly fee – unequivocally requires investment adviser registration as being in the business of delivering advice for compensation.

Of course, it is a part of the broker-dealer exemption that to avoid RIA registration for broker-dealers, the advice must be “solely incidental” to the sale of brokerage services, and the broker must receive “no special compensation”, which the SEC has defined as a fee or other compensation that is not traditional broker-dealer compensation (e.g., commissions or markups).

Yet ultimately, the SEC has effectively re-defined the broker-dealer exemption that advice for a fee (i.e., special compensation) is an RIA activity, but transactional advice from a broker that is compensated by commissions is not an RIA activity… ignoring that the Investment Advisers Act actually states that the exemption only applies if there is no special compensation and the advice is no more than solely incidental. In other words, receiving a fee is only one way to trigger investment adviser registration, and the other trigger is simply providing more-than-solely-incidental advice, while the SEC’s Regulation Best Interest treats it as the only trigger, and that advice compensated by not-special-compensation brokerage commissions is exempt… when the plain language of the broker-dealer exemption clearly shows that it should be RIA (fiduciary) advice, even when only episodic!

How Regulation Best Interest’s Title Reform For Dual-Registered Financial Planners Condones Confusing Hat-Switching

In determining when or whether to apply a fiduciary standard to financial advice (i.e., require registration as an investment adviser, or lift the standard for brokers up to that of investment advisers), ultimately there are two fundamental issues to consider.

The first issue is whether the individual is in the business of providing such financial advice for compensation – which would require investment adviser registration and apply a fiduciary duty. And the second is whether the individual holds out as and markets as a financial advisor, and creating the expectation that the recommendations they provide are such financial advice in the first place.

Notably, though, the investment adviser registration provisions of Section 202(a)(11) of the ’40 Act don’t automatically trigger investment adviser registration merely by the act of holding out and marketing as a “financial advisor” or similar title. RIA status is based on being in the business of advice (for compensation), not solely by virtue of marketing as such.

However, both broker-dealers under FINRA Rule 2210 and registered investment advisers under Rule 206 have an obligation not to engage in any form of misleading advertising about the nature of the services they provide. Which, arguably, should include the titles that are used when they hold out, because of what those titles imply about the scope of services they will or will not provide to consumers.

Accordingly, in its discussion of title reform – and whether the titles that advisors use should be further regulated – the SEC declined to enact a requirement that using a “financial advisor” or similar title alone should trigger investment adviser registration, as technically the mere holding out as a financial advisor doesn’t necessarily mean more-than-solely-incidental advice is actually being provided. And instead, the SEC declared under Regulation Best Interest that brokers who are operating solely under a broker-dealer will not be permitted to use the title in the first place, as doing so would fundamentally violate their Disclosure obligation to accurately describe the capacity in which they are serving.

However, in the case of dual-registrants – who maintain both a broker-dealer and an RIA license – the SEC declined to limit the use of the “financial advisor” title, as the broker might be acting as an advisor at the time of implementation… even though it’s also just as possible that the dual-registrant may be engaged as a non-advisor broker instead. Instead, the dual-registrant is expected to disclose that they may act in multiple different capacities – as an investment adviser or under a broker-dealer – and that in practice some recommendations may be implemented as an investment adviser (in the form of a managed account), and some as a broker (where any advice provided was solely incidental).

Except in the case of a financial planner delivering a comprehensive financial plan, and especially one who holds out as providing such comprehensive financial plans in the first place, arguably the entire engagement itself is an advice relationship in the first place. Such that any subsequent recommendation can no longer be solely incidental advice – when financial planning advice was the purpose of the engagement in the first place – and that marketing as providing comprehensive financial planning advice and then implementing such advice can never convert such advice, after the fact, to be solely incidental to the sale of a brokerage product. As the very marketing of such comprehensive financial planning advice creates an expectation of a holistic advice relationship in the first place.

In fact, when considering a broker-dealer exemption for fee-based brokerage accounts in 2005, the SEC explicitly recognized then that the very nature of comprehensive financial planning advice is too broad to ever be solely incidental, stating at the time that:

When a broker-dealer provides advice as part of a financial plan or in connection with providing planning services, a broker-dealer provides advice that is not solely incidental if it: (i) holds itself out to the public as a financial planner or as providing financial planning services; or (ii) delivers to its customer a financial plan; or (iii) represents to the customer that the advice is provided as part of a financial plan or financial planning services.

Which is notable both because the SEC chose at the time specifically to treat both the delivery of financial planning, or holding out as a financial planner, or representing to a client that its recommendations were made pursuant to a financial plan, all as requiring investment adviser registration. And because, bizarrely, the SEC contradicted itself in Regulation Best Interest by stating that “We recognize that, in adopting the fee-based brokerage rule in 2005, we declined to place any limitations on how a broker-dealer may hold itself out or the titles it may employ.” When in reality the SEC specifically created a limitation in the 2005 rule to do just that – place limitations on how broker-dealers hold themselves out when it comes to financial planning – that limitation on financial planning not being solely incidental that was ignored in Regulation Best Interest. Instead, the SEC permits the dual-registrant to hold out as a comprehensive financial planner – an RIA advice activity – but then only holds the dual-registrant accountable as an RIA when the management of an investment account (and not the comprehensive advice he/she marketed themselves as delivering).

Or stated more simply, when a financial advisor holds out with a title as such, and promises to deliver comprehensive financial planning, and actually delivers the plan, and then implements recommendations pursuant to the advice provided in the plan… it is inherently misleading to subsequently implement those recommendations subject to a lower Regulation Best Interest standard, when the title used and services offered clearly implied a holistic advice offering (not an advice relationship that is in connection with brokerage services that haven’t even yet been engaged!)!

The Broad Scope Of Financial Planning Is Incompatible With Narrow Regulation Best Interest

In the end, the fundamental problem is that the broad and comprehensive scope of financial planning advice is simply incompatible with Regulation Best Interest’s narrow (and contradictory to the ’40 Act) view of what constitutes being in the business of investment advice.

Holding out as a financial planner, and delivering a comprehensive financial plan, is a fundamentally advisory activity by its nature – so much so that providing such services unequivocally requires investment adviser registration – and as such, goes far beyond anything that could possibly be deemed as “solely incidental” to the sale of brokerage products. Especially when the financial planner begins the relationship with a(n advice-centric) financial plan, and only subsequently introduces their brokerage services (which can’t modify the nature and scope of the relationship after the fact!).

And again, this challenge in the conflict of holding out as a financial planner and then subsequently converting the relationship to brokerage later was something the SEC itself recognized when it issued a modification to the solely incidental exemption in 2005 (that all financial planning advice, or holding out as such, cannot be solely incidental to the sale of brokerage services)… a definition of solely incidental that disappeared when the entire rule permitting a broker-dealer exemption for fee-based accounts was struck down in FPA vs SEC (because when the courts vacated the rule, they vacated the entire rule, including the recognition that financial planning cannot be solely incidental advice).

Yet in its final version of Regulation Best Interest, the SEC not only declined to re-institute its 2005 acknowledgement that financial planning and holding out as a financial planner cannot be solely incidental to the sale of brokerage products, it inexplicably denied that it ever did so in 2005, and instead further expanded the breadth of solely incidental by turning any financial plan that would normally require investment adviser registration into one that is subject to the lower Regulation Best Interest standard merely because it is delivered in connection with the sale of brokerage products. And similarly declined to either attach an RIA registration requirement to holding out as a financial planner – as the SEC did in 2005 – or deem it misleading to market using financial planner titles and offering financial planning services while wearing the “RIA hat” even when the subsequent implementation of that plan will no longer be in an advisory capacity. Even as the SEC itself stated in its interpretation of an RIA’s fiduciary obligations as a part of Regulation Best Interest that “the Investment Adviser’s fiduciary relationship is broad and applies to the entire advisor-client relationship”.

Which is why XY Planning Network has filed a lawsuit against the SEC over Regulation Best Interest. Because it’s not appropriate for the SEC to put brokers marketing themselves as financial planners and delivering a comprehensive financial plan to a different and lower regulatory standard than what applies to anyone else (who must register as an investment adviser and be subject to RIA standards), solely because the brokers are delivering the plan in connection with the sale of brokerage products. Which effectively allows brokers who choose a more conflicted model of financial planning to have a lower standard, for the privilege of delivering that comprehensive planning advice in connection with the sale of brokerage products! If anything, the fact that brokers are using a financial plan to sell products should subject the financial plan advice and recommendations to a higher standard due to the conflict of interest, not a lower standard! Which is exactly what Dodd-Frank Section 913(g) would have required (if the SEC didn’t simply require such financial planning to trigger RIA registration in the first place, as it did with its 2005 broker-dealer exemption).

Where The XYPN Vs. SEC Lawsuit May Go From Here

So what happens next, now that XYPN has filed suit against the SEC?

The primary hope is simply that XYPN can prevail on the challenge against Regulation Best Interest, and ultimately have the rule vacated, either because the SEC failed to enact a standard for broker advice that was at least as stringent as the Investment Advisers Act (as required by Dodd-Frank), or alternatively that the SEC exceeded its Congressional authority by trying to overwrite and supersede the RIA registration requirements of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 and the solely incidental exemption for broker-dealers when it comes to the increasingly common and popular practice of providing financial planning in a broker-dealer (or in dual-registered status). In essence, Dodd-Frank required broker advice standards to rise to the level of RIAs, and the Investment Advisers Act requires advice to be delivered under an RIA’s standards in the first place… and the SEC chose not to follow neither of those laws in its promulgation of Regulation Best Interest.

If Reg BI is vacated, it takes the SEC back to the drawing board to try again in either instituting a new rule consistent with the Dodd-Frank requirements – that any new standard for brokers be at least as stringent as the fiduciary standard for RIAs – or alternatively, to just (begin to) better enforce the RIA registration requirements and the broker-dealer exemption as written, which requires the separation of sales from advice and would shift all financial planning advice to be under the RIA fiduciary umbrella (including the implementation of that financial planning advice).

Instead, the SEC might choose to amend Regulation Best Interest further – akin to how it amended the original 1999 fee-based exemption for broker-dealers in 2005 with respect to financial planning – to (re-)include the provisions of the 2005 rule that require holding out as a financial planner, delivering a financial plan, or representing that advice recommendations are being delivered pursuant to a financial plan, as not being solely incidental and requiring investment adviser registration (and the fiduciary duty that attaches thereof). Which would allow Reg BI to remain for the recommendations that are still being delivered by brokers, but shift financial planning advice out from under the purview of FINRA and Regulation Best Interest, and under the RIA umbrella where all advice is supposed to be delivered anyway… ameliorating XYPN’s concerns about the (literal) double-standard that applies for financial planning advice, to the point that it would no longer have a need to challenge Regulation Best Interest.

Notably, though, the point of XYPN’s lawsuit is not to impair the broker-dealer model itself – which, as noted earlier, is essential for capital formation and the operation of secondary markets. Instead, we simply believe that brokerage firms should be allowed to remain brokerage firms… and that in fact, it’s better for brokerage firms to not be held to a fiduciary standard that would make it difficult to fulfill their fundamental business purpose as broker-dealers (which is an inherently sales-based activity). The purpose of the lawsuit is merely to recognize that financial planning is a fundamentally advice-based activity, and that the SEC’s Regulation Best Interest fails to consider that reality in light of what the Investment Advisers Act already states. (And if broker-dealers continue to provide financial planning advice, they should be held to a fiduciary standard, as Dodd-Frank 913(g) would have required.)

Or stated more simply… for nearly 80 years, Congress has mandated a separation of sales activity (the natural business of a broker-dealer) from the delivery of financial advice (the natural business of an RIA), but the technology-driven convergence of the RIA and broker-dealer channels, coupled with the rise of financial planning and CFP certification, has led to the point where broker-dealers are marketing and holding out as providing financial planning advice, and actually delivering such plans, while relying on the standards that apply to brokerage sales activity and not the standards for the advice they’re actually marketing and delivering.

Which means ultimately, the SEC must either follow Dodd-Frank 913(g) and apply an equal standard for equal advice… or follow what the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 has required all along, which is that advice must be delivered as a registered investment adviser subject to a fiduciary standard, and simply let brokers be brokers (who represent themselves as such to the public when marketing their services).

Disclosure: Michael Kitces is a co-founder of XY Planning Network, which was mentioned in this article.

A bit of trivia: Justice Kavanaugh was the deciding vote in the 2-1 FPA v SEC Court of Appeals decision. Merrick Garland wrote the dissenting opinion.

Huh! I knew that Justice Kavanaugh was the deciding vote. I didn’t realize Garland wrote the dissent. Small world!? 🙂

– Michael

I nearly cried reading this. Well done.

WOW! This is a fantastic write up and just increased my respect of the XY Network. For fun you can read the eight attorney generals lawsuit as well, the article linked below has a download. Is there any indication that the FPA or the CFP Board is going to challenge Reg BI as well?

https://www.pionline.com/courts/eight-attorneys-general-sue-sec-over-reg-bi-concerns

Jason,

Thanks for the kind words.

I wouldn’t expect the CFP Board to challenge the rule, as they likely wouldn’t be able to demonstrate standing.

The FPA would have been a natural contender to challenge the rule – they’re literally the ones who challenged, and won, the last version of this in 2005 – but the FPA has been silent on the issue, and at this point the deadline to file a lawsuit to challenge the rule has already passed. (That’s why all the lawsuits flew last week – it was the final deadline.)

– MIchael

Thanks Michael!

This article I feel makes them obvious parties to join this lawsuit next

It’s too late for the FPA to join. The deadline passed last week. 🙁

– Michael

I think that will take us to a place where just the use of the CFP marks may not be allowed for those only registered as an RR and not an IAR.

Leo,

Arguably that’s already a potential outcome for those who are solely registered reps, given that even the current Regulation Best Interest doesn’t allow such individuals to use the “financial advisor” title (and almost certainly wouldn’t allow “Certified Financial Planner Professional” for the same reason?).

– Michael

WOW! My utmost respect and admiration to Kitces and XYPN for standing up to the SEC. Very few people/organizations have this level of courage (and even fewer live to tell about it). GOOD LUCK!

Be sure to share your kickstarter link to help fund this lawsuit.

Well, umm… I do hope we at least live to tell about it. 🙂

Thanks Matt!

– Michael

No doubt! Kudos XYPN

Good explanation and excellent job for XYPN to take this on.

One additional point, probably not part of the lawsuit but important to remember, is that the dual licence people have their clients sign FINRA mandatory arbitration. So even when acting as an IAR/RIA and giving advice as a fiduciary, when it come to legally holding FINRA registered advisor to the fiduciary standard, it does not happen. They are held to the FINRA suitability standard. Even if the person is holding themselves out as a CFP, promoting financial planning, taking a fee for a financial plan, once that arbitration agreement is signed, which is build into the brokerage agreement, the FINRA arbitration is final.

This then begs the question. Should one be allowed to hold oneself out as a CFP, who is a fiduciary, if one can not be legally held to the fiduciary standard? It is clear with the new CFP rules, that every CFP is always a fiduciary. Will the CFP BOS step up and actually revoke the CFP designation from all the advisors who are licensed as an RIA only? It is only the RIA, without any FINRA affiliation, who can be legally held to the fiduciary standard at all times with all clients.