Executive Summary

Having a mortgage is often framed as a way for an inflation hedge. As the conventional wisdom goes, with a mortgage your monthly payment is locked in (assuming it’s not an Adjustable-Rate Mortgage [ARM]), even if inflation goes up and interest rates rise. In fact, rising inflation would just devalue the mortgage in nominal (future) dollars.

Yet the reality is that ultimately, a mortgage may be paid off with inflation-adjusted wages, free up funds to be invested into inflation-hedging vehicles (from TIPS to equities), used to create a reserve for investing in bonds at higher rates in the future (a form of call option on interest rates), or be deployed to purchase a residence that provides a hedge against rising rents. In all of these scenarios, though, it is actually how the mortgage-related funds are deployed, or the income sources used to fund it, that are the actual inflation hedges… not the mortgage itself!

Ultimately, this doesn’t mean that a mortgage can’t indirect lead to beneficial outcomes if inflation (and interest rates) rise. But in the end, the benefits will not actually come from the use of the mortgage itself as an inflation hedge, but the other inflation-adjusted assets and income an individual has to support the mortgage instead! Of course, the caveat is that the use of leverage to hedge inflation can cut both ways, and magnify the unfavorable outcomes in non-inflation scenarios as well!

Why A Mortgage Is Not An Inflation Hedge

While a mortgage is often viewed as an inflation hedge, due to its fixed (at least with a conventional mortgage) payments that don’t change even if inflation arises, the reality is that a mortgage alone isn’t really a hedge that benefits from inflation. It’s not necessarily harmed by inflation, but it’s not a benefit, either.

To understand why, imagine for a moment that someone has a $500,000 house, and decides to take out a $400,000 30-year (fixed) mortgage at 4%. To avoid getting into a future cash crunch, the individual then takes the $400,000 in proceeds, and uses them to buy a series of laddered bonds that have a comparable yield to secure each mortgage payment as needed. This “perfect” asset-liability matching effectively immunizes against any risk that a change in interest rates could adversely impact the situation (assuming there are no bond defaults).

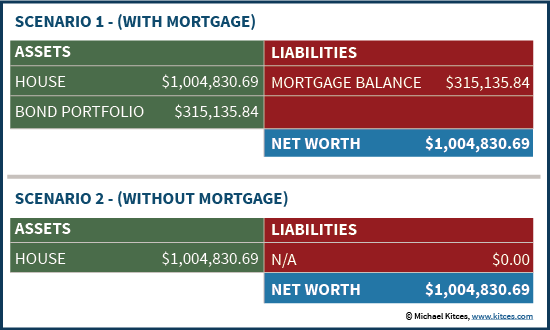

Now imagine that after engaging in this strategy, inflation really does spike higher. Suddenly, inflation is running at 7%. Intermediate-term interest rates jump close to 10%. Within the span of a decade, the value of the house itself has doubled to $1,000,000 (just keeping pace with inflation). Given this “surprise” inflation event, the chart below shows the individual’s current financial situation, comparing the scenario with a mortgage (which would have amortized down to a remaining balance of about $315k) versus the alternative scenario without ever bothering to get the mortgage.

As the results reveal, the final (after-inflation) net worth in the two scenarios is the same! The presence of the mortgage itself, with the mortgage payment obligations managed by a bond portfolio at a similar interest rate to cover the requisite payments, is not worth anything more than the scenario that eschews the mortgage and just keeps the property itself! Either way, the net worth is exactly the same.

And notably, it doesn’t matter whether inflation rises or falls, as long as the bond portfolio generates the sufficient/same yield to cover the obligations of the mortgage payments, the outcomes continue to always be identical (at least on a pre-tax basis, but generally on an after-tax basis as well, assuming bond interest is taxable and mortgage interest is deductible).

It’s Not How Much You Borrow, But What You Buy “On Mortgage” That Counts

Of course, the caveat to the scenario above is that the proceeds of the mortgage were used to acquire a portfolio of bonds that would immunize the mortgage payment obligation - for instance, a series of laddered bond portfolios that are not sensitive to changes in interest rates. On the other hand, if the funds were used for a different kind of investment, the outcome can be quite different as well.

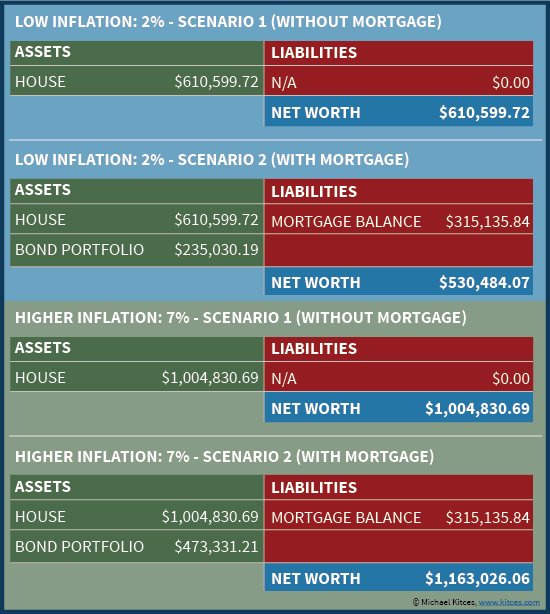

For instance, imagine instead that the proceeds were used to invest in a portfolio of TIPS bonds, with what (at the time of this writing) would be a real yield close to 0%. If inflation is only 2% (which means the TIPS pay a nominal yield of 2%), the bond portfolio is actually undermined by the 4% mortgage interest rate overtime, as the debt effectively “compounds” at 4% while the bonds only yield 2% (or in practice, the individual would have to liquidate an increasing quantity of TIPS bonds to cover the mortgage payments since the interest alone is insufficient).

However, if inflation again spikes to 7% instead, suddenly the outcomes are quite different. The TIPS bonds would now be producing a 7% return, providing more than enough nominal total return to cover the mortgage payments (or technically, TIPS principal would be increasing by enough that fewer and fewer TIPS bonds must be sold). Either way, the real estate itself is assumed to grow at the rate of inflation - which means its value will be the same with or without the mortgage.

The end result of these differing inflation scenarios after a 10-year period of time – now there is a significant difference in final wealth between holding a mortgage or not, depending on whether the individual goes through the high- or low-inflation scenario. If inflation is high, such that the (TIPS) bond portfolio outperforms the mortgage borrowing rate, the use of the mortgage results in the superior financial outcome. If inflation (and interest rates) stay low, though, the use of the mortgage actually results in less wealth.

As these scenarios reveal, while the presence of the mortgage itself doesn’t matter (as noted earlier), how the proceeds from the mortgage are allocated does matter. In fact, ultimately the outcomes were not actually dictated by the presence of the mortgage itself at all, but the decision to use (fixed rate) financing to purchase an investment that itself generates a lower or higher (nominal) rate of return based on inflation (the TIPS portfolio). In other words, the outcomes are not actually driven by the mortgage itself as an inflation hedge, but using the mortgage proceeds to buy an inflation hedge like TIPS “on mortgage”. And the strategy only works if the inflation hedge really does outperform the borrowing cost.

Likewise, if the portfolio was used to buy equities (which also function at least indirectly as an inflation hedge as rising inflation ultimately lifts nominal earnings and stock prices), the high-inflation scenarios may perform better than the low-inflation scenarios, but still not because the mortgage itself was an inflation hedge, but because a loan was used to purchase an actual inflation hedge (hopefully with enough expected return to justify the mortgage-leverage risk!). Or more generally, any time funds are borrowed to buy equities and the return on the investment is higher than its borrowing cost, a positive result occurs; that's simply the impact of investing with leverage and getting a favorable return - the only difference is that instead of funding the borrowing with a margin loan, it's being funded with a mortgage instead!

Similarly, if the mortgage is acquired with the hopes of leaving funds liquid to be reinvested in bonds in the future at higher rates (e.g., if rates rise fast enough, soon enough, the mortgage proceeds could be used to invest into future bonds that pay more than a current mortgage rate at a similar level of risk), the scenario is still one that will succeed – or not – by the returns that can ultimately be obtained by the portfolio. In essence, in this scenario the use of the mortgage to invest into bonds that may yield more in the future becomes a form of call option that will be “in the money” if rates rise enough to exceed the borrowing rate. The outcome may be better in high-inflation scenarios, but only because it causes the option “investment” to pay off - as higher inflation will generally result in higher interest rates, which means the portfolio return will exceed the borrowing cost - not as a function of the mortgage itself. On the other hand, if inflation (and rates) do not rise, this “interest rate call option” approach can become highly unfavorable as well, as the mortgage carries an interest rate of 4% and the investor earns 0% year after year, "waiting" for rates to rise!

Ultimately, as with most forms of leverage, using a mortgage to finance an investment into an inflation hedge (or other investment vehicle) can magnify the positive outcomes if the inflation hedge pays off, but it it magnify the negative outcomes if inflation does not come, too!

A Personal Residence As A Hedge Against (Rent) Inflation

In some situations, the reality is that there is no portfolio to match to the mortgage at all; the loan was necessary just to purchase the real estate in the first place. In other words, the scenario is not one of "own a house with no mortgage, versus having a mortgage and a [side] portfolio invested as an inflation hedge"; instead, it's "own a house with a mortgage, or rent because there's otherwise no way to afford the house at all."

Notably, though, even these situations where there's no portfolio to invest as an inflation hedge, the personal residence is not merely a “dormant” asset (given that it doesn’t provide an ongoing cash flow or income yield), it is actually still functioning as an inflation hedge. Not merely because the price of the real estate itself will tend to move in line with inflation, but because owning a personal residence actually does have an implied cash flow yield – in the form of the rental payments that are not being paid from cash flow.

Thus, for instance, if rents rise unexpectedly (or begin to inflate rapidly), owning real estate insulates the owner from any direct exposure to a higher rent obligation – which is especially valuable in situations where rental increases outpace wage growth. Or viewed another way, the residence pays a “yield” in the form of covering the equivalent of rental living expenses, and that yield is automatically implicitly indexed to inflation; if/when/as inflation lifts up, the amount of rent replaced by ownership of the residence automatically has risen as well. In other words, owning (and using a mortgage to do it) versus renting is a means of hedging against rent inflation.

Even in these scenarios, though, the reality is that the “benefit” of owning a residence to hedge against the impact of inflation on rents is actually a function of owning the residence, not a function of having a mortgage. Owning a personal residence rather than renting provides the hedge against rent inflation, whether the residence is financed with a mortgage or not! Of course, for those who do have the financial wherewithal, the choice of whether to finance the residence with a mortgage or not can be a secondary inflation hedge, but as shown earlier, for those who can afford the choice of having a mortgage or not the benefit is still about how the proceeds are invested and not the mortgage itself! For those who can't otherwise afford to own a residence as a hedge against rent inflation, though, the availability to use a mortgage is important because - once again - it buys access to an inflation hedge (in this case, the "rent-free" personal residence)!

Wages As An Inflation Hedge

It’s also notable that in situations where there is no separate portfolio or (material) assets and the mortgage is necessary to purchase a residence in the first place, the reality is that the mortgage will only eventually be paid off by (future) wages. In other words, the ability to pay off the mortgage (or not) will be driven almost entirely by what happens to future earnings. In turn, this means that to the extent inflation rears up, and wages benefit from the associated cost-of-living adjustments, the mortgage will become increasingly easier to pay "thanks to" inflation.

Even in this scenario, though, the key factor is still not that the mortgage is an “inflation” hedge, but that wages and the ability to work are an inflation hedge. If inflation does rise up, the mortgage may get “cheaper” relative to income and easier to pay, but not literally because the mortgage depreciated in value; instead, as noted earlier, the real driver is that wages will (tend to) rise in line with inflation, and it’s the wages-as-inflation-hedge that improve the outcome. After all, if someone is unemployed and has no other source of income, it’s pretty easy to see that inflation or not, it’s difficult to pay the (nominal) mortgage payments at all. Inflation doesn’t make the mortgage any cheaper in future dollars if there are no inflation-adjusting future dollars coming in to pay with in the first place; the mortgage still goes into default if there's no cash flow to make the payments, inflation-devalued or not! And if there are cash flows coming in to make the mortgage payments, then once again the benefit is the inflation-adjusting income source, not the mortgage itself!

The bottom line, though, is this: despite often being celebrated as an inflation hedge, having a mortgage itself does not actually function as such. A mortgage may free up assets to invest into an inflation hedge, or can be used to purchase a residence that functions as an inflation hedge, or be paid for with wages that are themselves inflation-hedged. But in the end, those outcomes are dictated by the inflation-hedging benefits of how the mortgage or its proceeds are used, or how it will be paid for… not by the mortgage itself! And as with any leverage, the outcomes can cut both ways, with mortgage leverage magnifying both the positive and negative scenarios!

So what do you think? Do you consider a mortgage to be an inflation hedge, or is it actually about how the mortgage funds are used? Have you ever recommended the use of a mortgage as an "inflation" hedge? Should more focus be given to how mortgages are used to gain access to inflation hedges?