Executive Summary

Disagreements over money are commonly cited as the number one reason couples divorce, and financial advisors often find themselves in the middle (or as the target!) of client fights. Yet while fighting and conflict are often thought of as negative activities that should be avoided (or simply ignored) as much as possible, the reality is that client conflicts are difficult to avoid and not easy to resolve, especially when they involve money, and in practice, not all client conflicts are negative. In fact, they can actually provide advisors with opportunities to better understand their clients and strengthen relationships – not only between the feuding clients but between the advisor and client as well!

Accordingly, advisors can leverage conflicts amongst clients with basic communication skills and mediation strategies to strengthen the relationship and, in some instances, even their bottom line. In one study that surveyed roughly 1,300 financial planners, researchers found that most (74%) of the respondents had very often worked with emotionally distraught clients, and that nearly half had mediated arguments between married couples. Furthermore, a majority of advisors in the same study indicated that by discussing sensitive, personal, non-financial issues with clients, they improved communication between family members, and seemed to promote better alignment of clients with their core values. And for 39% of the advisors, these discussions even helped to increase their business!

When helping clients through conflict, financial advisors may recognize the “four horsemen of the apocalypse” that include the types of unproductive fighting styles that can damage a relationship, such as criticism, contempt, defensiveness, and stonewalling. Of these ‘four horsemen’, stonewalling is the most dangerous as it can be an indicator that the fighting individuals have essentially given up on the relationship, accepting that there is no resolution to be found. By avoiding or reframing these communication styles, though, fighting can be a productive exercise in helping individuals better understand each other and brainstorm new ideas for collaboration, compromise, and agreement.

Important strategies for financial advisors who are interested in deepening their skills to help clients experiencing conflict include simple de-escalation techniques (e.g., using calm behavior, politely paraphrasing what the client says, and taking a short break from the situation). The goal of these techniques is to offer the agitated client a chance to cool off, to allow the advisor to empathetically connect with the client, and for everyone involved to catch their breath and remain objective.

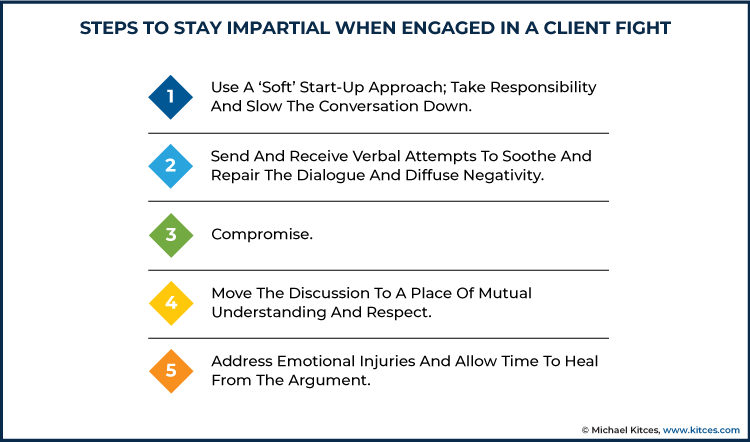

And when client fights involve the advisor as the target of anger or hostility, it is important for advisors to remain calm and impartial for the relationship with the client to continue developing over time. Some steps the advisor can use to maintain a healthy dialogue with their client include 1) using a ‘soft’ start-up approach by taking responsibility and slowing the conversation down, 2) sending and receiving verbal attempts to soothe and repair the dialogue and diffuse negativity, 3) being willing to compromise, 4) moving the conversation to a place of mutual understanding and respect, and 5) addressing emotional injuries as appropriate, allowing time for both parties to heal from the argument.

The key point is that advisors can ultimately benefit when helping their clients through difficult conflicts, even when they themselves are participants in these conflicts. And by learning when to use certain communication skills and mediation techniques to deal with client fights, advisors can better understand their clients, help them communicate more effectively with other family members, and develop deeper trust and long-lasting relationships with them.

Client Fights (Including Fights With The Financial Advisor) Are A Natural Hazard Of An Advisor’s Job… And Many Advisors Find That Good Can Come From Them!

It is not a surprise that people often fight about money. What may be surprising, however, is that fights about money can be extremely valuable, as they say a lot about a person’s attitudes toward money and personal wealth, not to mention their propensity for conflict. Accordingly, financial advisors who work with clients having fights about money (either in conflict with a family member(s) or with the advisor themselves) have an opportunity to learn about these important values, and perhaps even when to expect future conflicts to arise and what to do about them.

For instance, Research by Dr. Sarah Asebedo and Emily Purdon, published in the Journal of Financial Planning in 2018, uses conflict theory as a way to organize how people think about money and behaviors that surround it. Conflict theory offers a framework to view and understand relationships by examining the reasons why arguments arise in those relationships.

As such, organizing money concepts by conflict theory shows money as an obvious source of arguments because it is scarce (we fight when there isn’t enough to go around), it affects the actual and/or perceived distribution of power (we fight when someone with more money uses it as leverage or control), it (can) promote competition (we fight to have the most money), it is fundamental to preservation (we are willing to fight if our ability to take care of ourselves is threatened), and it is intertwined with personal values/beliefs (we fight if people don’t believe the same things we do about money).

Moreover, the lens of conflict theory makes it is easy to understand and even expect money as a source of conflict, as that is what theories often help us to do – to actually predict expected outcomes. As such, conflict theory may also help advisors predict when and why fights involving money are going to happen with their own clients.

For example, the distribution of power created by money is an obvious area of potential contention that can exist between married clients.

Example 1: Jack and Jill, a married couple, are expecting! They set a meeting with Penny, their financial planner, to discuss options for their growing family.

After accepting the meeting, as happy as Penny is for them, she is also feeling apprehensive and nervous about the meeting. Penny knows from prior work and meetings with the couple that Jill makes more than Jack and has always wanted Jack to stay at home with the baby. Yet, Jack loves his job, even though he makes a little less than Jill.

Penny recognizes that the distribution of power between Jack and Jill sets the stage for a major conflict between the couple. How does she prepare to referee this client-to-client fight?

Preservation is another area where the scarcity of (or fear of losing) money can lead to anxiety and disagreement that the advisor might experience with clients, and might even result in the advisor being identified by the client as the cause of their anxiety and fear, perhaps because the client may view the advisor as responsible for the growth (or lack thereof) of their assets.

Example 2: Penny also works with her long-time clients, Toni and Tim. Toni and Tim have always been nervous about the markets. Because of the recent turbulence caused by the Coronavirus, they have decided they want to come in to discuss their options.

During their call to set their meeting with Penny, Penny off-handedly says she looks forward to talking with them, but that the best thing for them to do is to ride it out.

At this point, Toni starts to get frustrated and actually yells at Penny over the phone, “You just never understand; you know how much we went through in 2008-2010, and if all you are ever going to tell us is to ride it out, then we are going to find a new financial advisor!”

How does Penny respond and prepare to de-escalate what is likely going to be her own client-to-advisor fight?

Client Fights Will Often Recur Throughout The Relationship And How Advisors Can Help Them Be More Productive

Notably, conflicts over money are likely NOT going to be ‘one-and-done’ ordeals. Instead, because these conflicts involve complex emotions and often hinge around unpredictable factors such as changing income levels and volatile economic conditions, they may never fully be resolved and will often be long-lasting, recurring arguments.

But this does not suggest that advisors should avoid trying to align the financial planning goals of couples. On the contrary, advisors can continue to harmonize client goals and can even use the opportunities to work through conflict as a means to deepen the relationship!

Dr. John Gottman, the famous couples’ researcher, praised for his work with couples, has found that 69% of issues that couples have are unsolvable, never-ending issues. The fact that conflict over money comes up, again and again, doesn’t need to be considered as a negative sign, though.

While advisors may become frustrated by going through the same motions and having the same discussions over and over again, they can instead trust that recurring conflicts about money are totally normal and simply an aspect of working with couples. They can even be an indicator of a healthy relationship in which individuals are willing to communicate their values and beliefs with each other.

Furthermore, because couples are going to have these fights – again and again – financial advisors will have ongoing opportunities to help these clients work through their difficulties. Even though things may never get fully resolved, research shows that resolution isn’t really the main point – Dr. Gottman, along with other mental health practitioners specializing in couples, says the end goal isn’t to avoid fighting – instead, the goal is to fight better and more productively (more on this later in the article); that is absolutely where financial advisors can help.

Similarly, Asebedo and Purdon also find that money fights often go unresolved and actually tend to escalate, and that money arguments and divorce are highly related. To help advisors recognize the hallmarks of ‘good’ fighting gone ‘bad’, we can again turn to the research from Dr. Gottman. In his years of studying couples and how they fight (literally inviting couples to live in an apartment full of video cameras), he has been able to organize four unproductive fighting styles into what he calls the “four horsemen of the apocalypse”, which financial advisors have likely encountered in client meetings.

Criticism: Makes negative judgments about the other’s character.

Example: You never want to think about how our financial situation impacts me. You’re just selfish.

Contempt: Attacks character and puts one member of the couple in the role of moral superior.

Example: You think that because you are the bread-winner, you can just do what you want when you come home. You do not care about me or the kids, in fact, you just make more mess for me…just like having another kid. Pathetic.

Defensiveness: Responds with a heightened sense of self-preservation at any comment.

Example: Wife to Husband (innocently): Did you remember to bring the paperwork for the new account?

Husband to Wife (feeling attacked): No, you know how busy I am! How could I possibly remember that? I barely made it to the meeting on time! In fact, you knew how busy I was today and scheduled this meeting anyway, why didn’t you remember to bring the paperwork.

Stonewalling: Shuts down completely; one or both members of the couple stop responding altogether.

According to the research, stonewalling is generally the worst of the “four horsemen” because silence can indicate that the couple has given up on communication and that, essentially, they no longer feel they have a relationship worth fighting for and that no resolution can be found. Moreover, if the silent treatment is the worst, then despite the fact that fighting can be uncomfortable, the fact that fighting is even taking place can suggest that there is still hope for a resolution to be found.

However, as often seen in therapy and suggested by fight research, fighting does not necessarily have to escalate to stonewalling or even to divorce if clients are able to use their inevitable fighting for good and, instead of seeing conflict as simply a ‘fight’, to view their conflict as a brainstorming exercise.

For instance, if Penny, our financial advisor in the examples above, uses her meeting with her clients as an opportunity to brainstorm for new ideas, her thought process with Jack and Jill might look something like this:

Example 3: Penny decides to think ahead and actually plans an exercise for Jack and Jill to get them brainstorming through many different scenarios, instead of only focusing on the scenario with the most tension: Jack staying home.

For instance, Penny knows that power is an ongoing issue for Jack and Jill, but they have been able to resolve other financially motivated power-struggles in the past. Therefore, one of the exercises Penny plans is to actually get Jack and Jill to discuss another financial power-struggle that they overcame.

Penny accepts that she is once again tasked to help Jack and Jill align their goals and that this probably won’t be the last time.

The same can go for dealing with conflicts that arise between advisors and their clients, which can follow a similar pattern of continuing again and again.

For instance, in Example 2, our financial advisor Penny has experienced conflict with her clients, Toni and Tim. The fear and pain that the client associates with market turbulence have brought them in to see Penny many times in the past. For instance, Penny went around and around with Toni and Tim trying to talk them out of going to cash and ultimately had to yield to their wishes to keep the relationship.

Penny believes that simply firing them, or holding her ground and forcing their hand to fire her, would have only made things worse for the client. She doesn’t like fighting with them, but she believes a little push-back from her is better than letting them fare on their own. Unsurprisingly, Toni’s fear from 2008-2010 remains unresolved, which is likely why, in today’s meeting, her fear has escalated and is coming out as anger.

Example 4: Penny, a bit stunned at first by Toni’s threat to find a new financial advisor (Penny thought they were past that), does remember how hard 2008-2010 was for Toni and Tim (and their past threats).

Thankfully Penny also knows from reading the Nerd’s Eye View blog that clients experiencing stress respond well to ‘to-do’ lists.

As such, Penny re-vamps her typical turbulence speech and tells Toni that they will spend time during their meeting to formulate a to-do list for them to work on together.

For example, Penny knows from the last tough market cycle that Tim and Toni really like the idea of selling. As such, at least one action item on the to-do list involves helping Tim and Toni choose what to sell that would be the least damaging to the overall portfolio, but that would also help them to maintain a sense of control.

It is important to remember that while financial advisors are usually very comfortable talking about money, it can be a difficult topic of discussion for many others – not just because having conversations with others about money can be stressful and uncomfortable, but also because many people have difficulty understanding their own complex relationships with money. Thus, it is not uncommon for problems/issues to go undiscussed or unresolved between clients, and then, once in the advisor’s office, the clients erupt into a fight over a long undiscussed and unresolved issue.

We can again turn to the conflict theory work by Asebedo and Purdon and the research by Dr. Gottman for more insight about why this happens. According to their research, couples have ongoing fights that never truly end because each member of the couple brings their own individuality to the relationship.

A couple is, by definition, a union of two different individuals who have agreed to come together and share their life today, but who have unique lives and lessons that were likely different as they each grew up. In some cases, the experiences of each individual in a couple can be radically different and can still have a significant impact on their lives today.

And these differences, compounded by the likelihood that each individual may dislike (or have difficulty with) discussing money, may be brought to the surface in financial planning meetings.

Or stated more simply: an in-depth financial planning process can actually increase the likelihood that money conflict issues between couples come to light (and potentially as a fight)!

Financial Advisors Can Connect With Clients In Conflict With Good Communication Skills And The Ability To Mediate

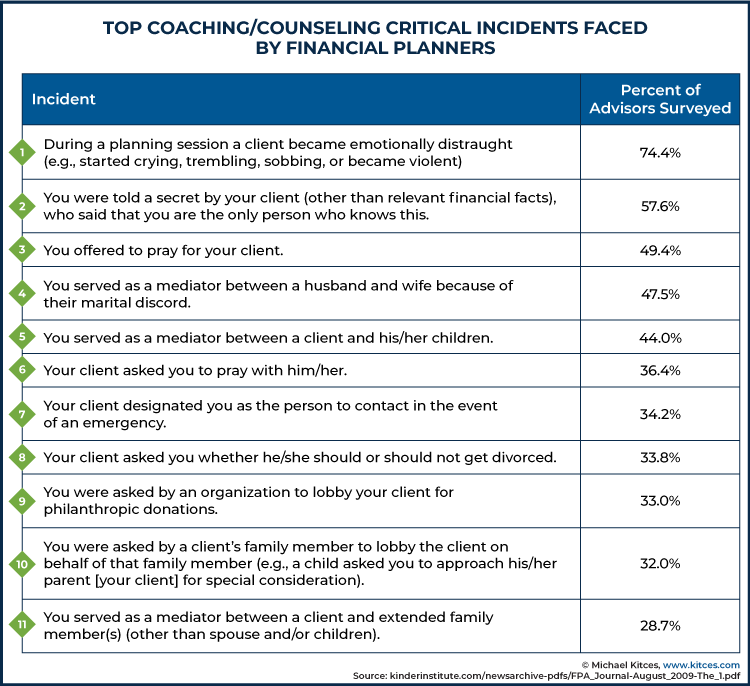

The impact of client conflict on financial advisors is emphasized by research done by Dubofsky and Sussman in 2009. In their work, they interviewed 1,374 financial planners about the job tasks that fall outside of the traditional seven areas of financial planning (i.e., investments, insurance, retirement, cash flow management, estate planning, and education planning) and found that financial planners rank communication and mediation training as important skills because of their extra job duties identified in the study.

Dubofsky and Sussman found that nearly half of the financial planners interviewed served as mediators in client-to-client fights (such as in Example 1 with Jack and Jill). Furthermore, 47.5% of advisors reported that they were mediators between a husband and wife during marital discord, 44% served as a mediator between the client and the client’s children, and 28.7% were asked to serve as a mediator between the client and the client’s extended family.

Financial planners also indicated that they very often worked with emotionally distraught clients, like those of Toni and Tim in Example 2. In fact, 74.4% of advisors agreed with the statement, “During a planning session, a client became emotionally distraught (e.g., started crying, trembling, sobbing…).

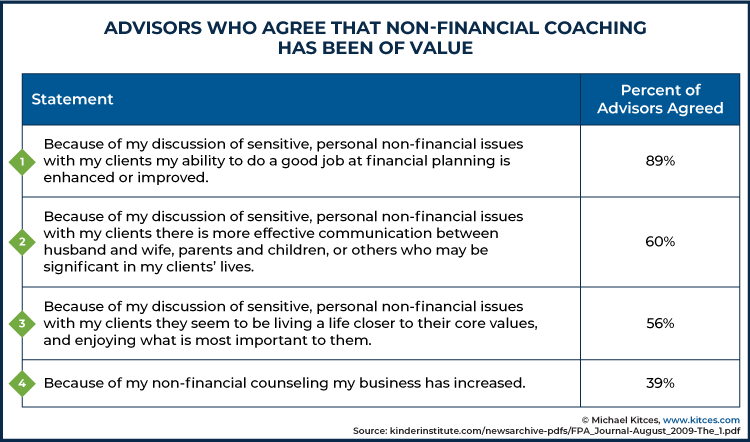

Furthermore, an important question that often arises is whether financial advisors should even involve themselves in mediating arguments. Many advisors who do involve themselves in these ‘extra’ job duties tend to agree that being able to work in these areas helps their clients.

For example, 60% of advisors agreed with the statement, “Because of my discussion of sensitive, personal non-financial issues with my clients there is more effective communication between husband and wife, parents and child, or others who may be significant in my client’s lives.” And 56% of advisors agreed with the statement, “Because of my discussion of sensitive, personal non-financial issues with my clients, they seem to be living a life closer to their core values and enjoying what is most important to them.”

Additionally, financial advisors in Dubofsky and Sussman’s study reported that while getting involved in a client argument may be scary, it ultimately improved their ability to do financial planning. 89% of advisors agreed with the statement, “Because of my discussion of sensitive, personal non-financial issues with my clients, my ability to do a good job at financial planning is enhanced and improved.”

Research from financial therapy would also align with what these practitioners are communicating. Basically, when clients fight, they will stay stuck until they can come to a resolution. If advisors can help get clients over or through the fight and help them get un-stuck, then they can go back to doing financial planning.

And if that isn’t enough, just to be able to do one’s job and be less stifled by conflict that advisors know they will face, Dubofsky and Sussman also found that some financial planners even thought their ability to help clients through disagreements increased their business – apparently, an ‘argument’ niche could be a thing!

In the study, 39% of advisors agreed with the statement, “Because of my non-financial counseling, my business has increased.” And they are not the only ones; our own Kitces Research Study on marketing found that advisors with niches (although not specifically asking about a ‘fight’ niche) tended to spend less on marketing, perhaps because their marketing could be more direct, and niche marketing was also found to be more enjoyable.

How Advisors Can Help Clients Proactively Handle Future Fights

It is extremely important to recognize that fights are inevitable, and being aware of and prepared for them can be a useful practice consideration for financial advisors. So even for those who don’t want to specialize in conflict resolution, it is still good to know how to de-escalate situations when conflicts do arise: Be calm, politely paraphrase, and take a walk.

Techniques For Advisors To De-Escalate Conflict Situations

In the context of client conflict resolution, in particular, there are two primary benefits to being calm and polite.

Speaking calmly, gently, and slowly will keep the advisor’s heart rate in check, ensuring that the advisor stays calm in a potentially heated situation. Speaking calmly, gently, and slowly, also calms the upset person.

As it pertains to being polite, this can be as simple as asking permission and saying please (which in the heat of the moment is easier said than done). For instance, advisors may calmly and politely ask the client to please sit down or to refrain from yelling, or they may also ask permission to make a suggestion if the client takes a moment to pause during their tirade.

Financial advisors can also politely, as part of the suggestion, repeat back to the client what they have just heard the client say to them or to their partner. Summarizing or repeating back to the person what was just heard establishes empathy. The advisor may want to establish empathy with the client themselves when working through a client-client fight.

While empathy is key to calming the agitated party and ensuring that they are heard, it also allows the advisor to remain on an objective playing field with both parties, as the advisor isn’t required to take sides with either party when expressing empathy with one or the other.

Example 5: Penny is 30 minutes into her meeting with her clients, Jack and Jill.

Jack says to Jill, “You are not listening; in fact, you never listen. My work is more than a job; it is my passion. All you care about is your job. You are being selfish”.

Jill snaps back, “I’m selfish?!? You are the selfish one! I am trying to figure out how to do what is best for our baby and, at the same time, support our family, and all you seem to care about is yourself and ‘following your passion’!”

Penny recognizes two of the apocalyptic horsemen, criticism and contempt, and knows that she must redirect while avoiding taking sides.

Penny responds calmly and with empathy, “Please, may I interject? I believe there is good dialog going on here. I want to step back a moment, and thank you for both being willing to talk through these ideas today. This is tough stuff. Jack, based on your comment, I hear you saying your work offers an important outlet. Jill, I hear you saying you are concerned about the changing family dynamic and schedules. Am I hearing you both correctly?”

Jack and Jill agree that Penny has correctly articulated their individual needs.

Penny then says, “Great, let’s re-start our brainstorming session there. Jack, tell me some other ways in which you can access your passion? Jill, describe for me your perfect future schedule? We will likely not land on a perfect compromise, but I believe we can find ways to proactively address your individual needs and work toward the same goal, together”.

Last but not least, taking a walk (or some type of break, be it to get a drink of water or simply to stretch) is a very useful technique to simply de-escalate the situation, and the best part about it may be that there is really little to no talking required.

Why take a walk if there is yelling or silence? The answer is that when clients are in shut-down or fight mode, their subconscious, emotional bodies are flooded with stress-related hormones. And when clients’ bodies are gearing up for fight or freeze mode, they need to take a moment so that their autonomic nervous system (the regulatory mechanism that controls various bodily functions, including our ‘fight-or-flight’ response) can recover and once again feel safe. Taking a walk, getting a drink of water, or taking a break provides time for the body to come out of its fight-or-flight response.

Furthermore, while the take-a-walk-technique can be deployed to de-escalate a situation and may be easier to do than to talk through a fight, it is not necessarily easy; in fact, it might even be tricky to recognize when to effectively use it. Generally, the take-a-walk method is probably best at the extremes – when there is yelling or if there is silence.

In the examples with Jack and Jill, above, the financial advisor, Penny, is employing some pretty advanced communication skills, which are not easy to do in the heat of the moment without practice (so if you do want to be like Penny, visit the Financial Therapy Association and check out their education programs, which include training on communication techniques seen above).

Example 6: Penny is not 15 minutes into her virtual meeting (social distancing at work) with her clients Toni and Tim, who had already expressed concern about not sitting still through another 2008-2010 bear market when Toni starts to raise her voice.

Toni says to Penny, “Penny, I have already told you! I will not go through this again! I am not just going to go quietly and sit idly! I am already having nightmares. I am already feeling the impact of the Coronavirus, and we do not even know if we have yet seen the worst of it! No, no, no, Penny, doing ‘nothing’ is not an answer!”

Penny takes a deep breath and thinks, “What!! I am doing the best that I can here! I cannot control the dang markets!”

Yet, Penny knows this is defensiveness and that it wouldn’t be a helpful retort. She also recognizes that she is just staring blankly, silently into the computer screen as Toni and Tim stare back at her in silence.

Thankfully, Penny has the wherewithal to recognize that she is very rapidly becoming emotionally flooded and moving from defensiveness to stonewalling. And Penny also understands that Toni and Tim are in fight mode. It is time for a break.

Penny takes a second deep breath and says to Toni and Tim, “Forgive my pause and thank you for sharing with me what you are going through, this is an incredibly unsettling time, and it helps me to understand your perspective. Before continuing, though, would you mind if I took a 5-minute break to make a cup of tea? I think better with a cup of tea, and I want to give you my best as we reconvene and discuss some potential to-dos.”

In the above example, Penny and the client are fighting, so it is important for Penny to separate from the client in order to let both parties cool down. Penny has carried the burden of breaking up the meeting and requested that she separate herself, essentially without positioning the break as a punishment for bad behavior (for example, Penny did not say, “You are angry, so let’s break to cool down. Yelling is not productive, so let’s take five.”).

What is more, if, for example, it had been Jack and Jill fighting with each other, Penny might still suggest a walk or a break and invite Jack or Jill to a different room to grab tea, water, a beverage of any kind, or simply suggest a bathroom break.

The suggestion to break should be made calmly, avoid “you”/blame language, and function to separate the feuding parties.

Mediation Techniques Can Be Used To Leverage Conflict As A Good Source Of Brainstorming Ideas

Financial advisors who want to work through client conflicts and truly turn fights into brainstorming sessions should understand that, similar to de-escalation techniques, separation is still a key strategy. By starting out with separating the people from the problem (e.g., by setting the problem aside and focusing on the clients’ interests, instead), the advisor can avoid taking a position on a particular side. This sets the stage for brainstorming by encouraging ideas and ownership of action related to moving those ideas forward.

Research by Dr. Gottman supports the idea that when financial advisors notice that their clients criticize and use contempt toward each other, this is where they can be most helpful by separating the person from the problem.

Example 7: If a client says to their spouse, “You never want to think about how your spending impacts me. You’re just selfish”.

The financial planner restates this to separate the person from the problem and says, “I hear you saying that a review of the budget to get insight into where money is being spent would be a worthwhile exercise”.

When financial planners recognize that the fights may be stemming from differences at an individual level and that those fights are not likely ‘solvable’ issues, the financial advisor can help redirect the discussion to a larger problem that both clients can agree to attack.

The advisor can even help to foster and support generating options for mutual gain between the conflicting clients by putting the goals of the relationship before the goals of an individual, as well as help to establish objective criteria for how these goals will be carried out.

Basically, in order to work toward something together, it is often helpful that the other member of the couple knows, recognizes, and sees what that other member has said they will do.

Example 8: The clients who just went through the deep-dive of their budget were both surprised by their own spending habits, as well as the spending habits of their partner.

The advisor suggests, as a next step, instead of focusing on any one person’s ‘bad behavior’, they instead set a new goal as a couple and brainstorm how each individual can demonstrate ‘good behavior’ toward that goal.

Recognizing that the clients are starting to feel good about their commitment to ‘good behavior’ goals, the advisor helps facilitates a brainstorming session where the clients come up with ideas for a nice vacation as a reward for themselves. Excited about their new goal, the clients commit to putting money into an account to save up for their vacation.

The advisor also works together with the couple, helping each person come up with ways they can participate to meet their savings goals, encouraging them to acknowledge and appreciate each other’s commitments throughout the process. One member agrees to give up their daily Starbucks run; the other member agrees to prepare meals on Sundays and take their lunch to work 3 times a week.

Methods For Advisors To Remain Impartial When They Themselves Are In A Fight With A Client

Last but certainly not least, financial advisors should recognize that although this work is important and very often rewarding, it can also be difficult and potentially fight-inducing. As mentioned a few times before, when working with couples, it is important not to take sides, but that is much easier said than done. And it is totally possible that clients – like Penny’s clients, Toni and Tim, in Examples 2 and 4 and 6 – will be angry with the advisors.

More than just being able to help clients navigate their own fights, financial advisors in this arena also need to be aware that they themselves should know how to respond to a fight, as a participant of the fight, and move forward.

In order to create relationships with clients that will last and grow, advisors can work to nurture these relationships such that they don’t simply mediate fights, but actually grow together through them. Accordingly, even though it might be weird to think of responding to fights with clients similar to the ways that you might respond to a fight with a friend or your own family, the suggestions here are supported by couples’ counseling practices and also by the work done by couples’ researcher Dr. Gottman.

The first exercise is to practice using “I” statements and to create reminders to use them often so that in the heat of a fight, it will be easy for the advisor to frame the argument without succumbing to any of the ‘four horsemen of the apocalypse’. Essentially, unlike watching two clients fight, who may insult each other, advisors obviously won’t be trading insults with the client and will instead need to express themselves in a more productive and professional way.

Advisors can do this by first starting with reflective listening/paraphrasing. Let the client know they are being heard. And even with this dialogue, paraphrasing can be offered in an “I” statement form; for example, “Thank you for sharing X, I hear you saying X”. Then, if needed, advisors can also use an “I” statement to voice their own concerns.

Example 9: Penny has just started working with a new coupled-client, Bob and Barb. Bob and Barb decided in the wake of COVID-19 that they should really talk to someone and have reached out for professional financial advice for the first time.

During their third meeting together, Penny reviews recommendations in Bob and Barb’s newly created financial plan. At every turn, she feels as if Bob is competing with her, contradicting the advice, and even undermining the plan and recommendations.

Penny, sensing her own growing frustration and Bob’s overt disapproval, decides to take a breath and says, “Bob, thank you for providing so much feedback. I hear you letting me know that this is an area you have really thought a lot about. However, I’m also feeling that I am not hitting the mark for you. Let’s stop the recommendation for a moment and talk more about your goals.”

Now, if you are thinking, “I could not be Penny. There is no way an ‘I’ statement would make it past my lips!” you are completely normal. Furthermore, research by Dr. Gottman actually speaks to the fact that when we are ones being fought with, it is really hard to remember to use mediation techniques. For this reason, Gottman developed his own suggestions for how to navigate an argument.

First, use a soft start-up, resist the urge to criticize, and avoid contempt. In order to do this, the advisor can take blame or responsibility, and can then slow the conversation down and simply describe what is happening. The advisor should focus on remaining polite and hopefully grateful that the client, although angry, has not yet decided to stonewall and simply fire them, giving up on the relationship.

Next, sending and receiving verbal attempts to soothe and repair can diffuse negativity and keep the argument from escalating. In a married/committed relationship, this is done through speaking the other person’s ‘love language’. However, for a professional relationship in a work environment, this can be done by asking the client what they need in order to feel whole and how they would like to see the issue fixed.

Example 9 (continued): Penny is thinking in her head, “Sheesh…they came to me for advice, and I am just being put out at every turn. Why are they even here? Bob is just being a jerk”.

Yet, Penny knows to avoid criticizing and so she decides to start by just describing what is happening. She says, “Bob, you have a lot of ideas and opinions about the plan recommendations”.

Bob responds, “Yes, I have been doing our financial planning for years. I don’t really need this all explained to me – I am only here because Barb begged me.”

Penny, “Well, I apologize for perhaps taking too basic of an approach, is there an area where I can elaborate in greater detail; tell me how I can help and make this meeting worthwhile to you”.

The next phase of healthy arguing is compromise. While it might sound a bit weird to compromise with a client – after all, they are the customer, and customers are always right (right?) – compromise is less about the financial plan and more about how the advisor and the client can work together productively.

Furthermore, it is important to point out that this stage may actually take some time. True compromise can only come when one has a full understanding of each side’s needs – and discussing what those needs are will not necessarily be a short discussion.

The fourth step is to move away from apologizing or accepting blame, and instead to move with the client to a place of mutual understanding and respect.

Example 9 (continued): Bob is positively triggered by Penny’s comment. He had subconsciously been wanting Penny to ask, “Tell me how I can help”.

Bob explains that while he does want Penny’s input, he also wants full autonomy and oversight when it comes to portfolio changes and decisions. He has used an active investment approach for years and fully intends to continue that pattern.

Penny tells Bob that she hears him and is not trying to reduce his autonomy. She also lets him know that she is thankful to have a client who wants to actively engage in portfolio decisions. However, her firm takes a Modern Portfolio Theory approach and does not actively trade.

After a back and forth about why Bob wants to have this control, it comes out that he simply enjoys finding and investing in “the next big thing”. Penny suggests that she manage 80% of the portfolio, a calculation they ran together to ensure retirement needs can be met, and that she will stay out of Bob’s way to wheel and deal in his 20%.

Last but not least, fifth is addressing emotional injury and allowing time to heal from the argument. In the above example, Bob and Penny have managed to come to terms; however, this is not going to be the last time Penny has a dust-up with the client. Bob and Barb may still fight over power with Penny.

Similarly, Toni and Tim may still come to a meeting swinging, fighting for their self-preservation. And Jack and Jill will inevitably reach a new stalemate over their distribution of power that they will want Penny to help them sort out.

And future scenarios might not end as nicely as Penny’s and Bob’s just did. In fact, although on the surface it didn’t end in a bigger argument, Penny and Bob were able to come to a compromise, this is still very new for Bob and may feel like a fresh wound. Remember, he did not really want help from a financial planner, and it may take a long time for Bob to feel that he can trust Penny.

The key point to healing an emotional injury is to give it time and to apologize when an apology is due. Penny and Bob will continue to feel each other out, and Penny may find that she will need to apologize to Bob if his feelings are hurt over not being included. In these scenarios, the focus is on continually revising the plan to work together without offending, hurting, or frustrating the other party.

Ultimately, this is tough stuff. Yet, again, advisors who are learning to actively help their clients work through their fights find the experience rewarding.

Even those who do not want to focus on conflict resolution and mediation as the main aspect of their day-to-day job will still benefit from understanding the basics of why money arguments happen and how to de-escalate them.

THIS IS THE EMAIL OF THE MAN THAT RESTORED MY TWO YEARS BROKEN RELATIONSHIP, I LOST MY MAN TO ANOTHER LADY BUT NOW I HAVE MY MAN BACK FULLY TO MY SELF FOREVER, THIS IS AMAZING AND I AM SO GRATEFUL THAT EVERYTHING TURNED AROUND FOR GOOD, OUR LOVE IS STRONGER THAN BEFORE, HE SAID HE WILL NEVER LEAVE ME AGAIN..CONTACT IF YOU NEED HELP TO RESTORE YOUR RELATIONSHIP OR MARRIAGE. HE IS THE BEST, HE CAN ALSO CURE HERPES VIRUS EMAIL: [[ robinson.buckler [at] y a h o o .com ]]..!!!……[[ www. robinbuckler .c om ]]…………??

I AM FROM UNITED STATES….