Executive Summary

Many financial planning clients have spent much of their adult lives saving. Self-discipline and restraint may be key traits in building wealth, but when clients enter a phase of life where spending is more appropriate, they can hit a roadblock. Even when their plans support discretionary spending and they express a desire for it, they may find themselves unable to act. For advisors, this can be perplexing – and even frustrating! – when the numbers say "yes" but the client still says "no." However, underspending is rarely a purely financial issue. Instead, it's often shaped by deeply rooted values, personal identities, and psychological barriers. Understanding the reasons behind why clients underspend is essential not only for preserving client trust but also for supporting a more holistic, values-aligned use of wealth.

In this article, Meghaan Lurtz, behavioral finance expert and partner at Shaping Wealth, describes the psychological barriers that hold clients back and how advisors can gently help them experiment with spending more. By framing expenditures as low-stakes trials, advisors can help clients discover which expenditures truly add value – and which do not.

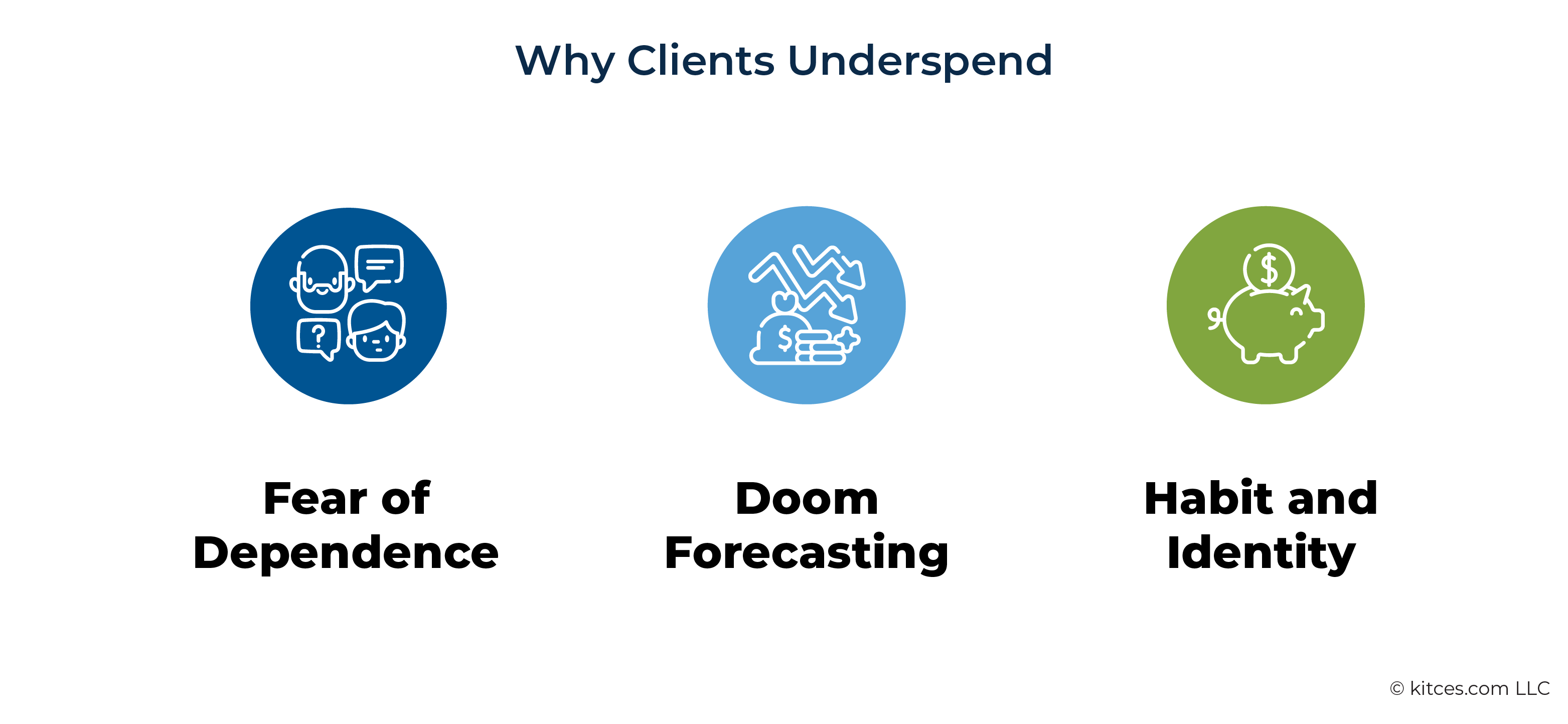

Common barriers include fear of future dependence ("What if I need this money later?"), doom forecasting (catastrophizing about worst-case scenarios), and a fixed saver identity that makes spending feel like betrayal. These patterns are reinforced by behavioral biases such as loss aversion and poor emotional forecasting. Even joyful experiences, like a family vacation, may be overshadowed by the psychological 'cost' of seeing account balances drop, making it challenging for clients to spend even when they logically know that they can.

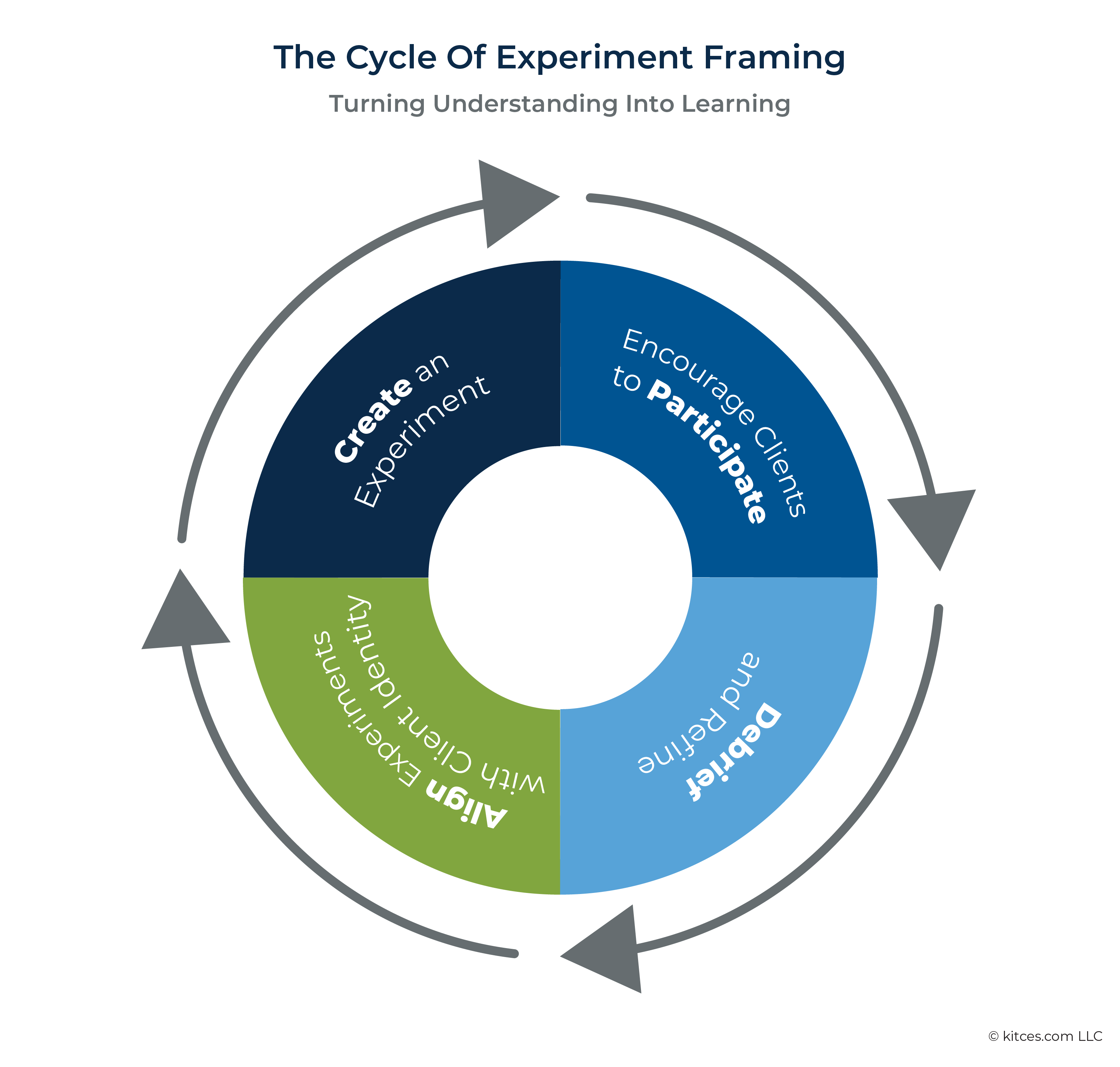

To address these barriers without undermining client agency or triggering defensive reactions, advisors can reframe spending as an experiment. These experiments are low-stakes, time-bound, and designed to generate feedback. This shifts the focus from identity ("I'm a spender now") to curiosity ("Let's see how this feels"). For instance, rather than recommending a wholesale shift to luxury travel, an advisor might suggest trying business class once on a meaningful trip. Clients gather 'emotional data' from the experience, which can then guide future decisions. Advisors support the process by designing the experiment, encouraging participation, facilitating a thoughtful debrief to separate value from extravagance, and aligning the results with the client's self-image as a responsible steward of wealth.

This iterative, feedback-driven process can be transformative. Experiments give clients permission to try new behaviors while preserving their sense of responsibility around money. Over time, these conversations shift spending from a moral referendum to a learning opportunity, helping clients clarify what truly brings joy and meaning. As clients build confidence in their ability to use money in ways that reflect their values and enhance their lives, they often become more open to further experiments, deepening both their financial well-being and their relationship with their advisor.

Ultimately, underspending isn't solved by pushing clients to spend more. It's about helping them align their money with the life they want – whether that means spending, giving, or simply feeling free to explore what's possible. By framing spending as experimentation, advisors can offer clients a safe, low-stakes way to test new behaviors, learn from the results, and ultimately unlock greater satisfaction and purpose. The shift from static planning to dynamic experimentation empowers clients to confidently align their wealth with what matters most!

Why Clients Underspend

For many financial advisors, one of the most surprising challenges isn't convincing clients to save more or cut spending, but helping them spend enough. Clients may reach retirement or receive a windfall with substantial wealth, yet continue living far below their means. On paper, their plan shows decades of financial security. In practice, though, they resist spending – even on purchases or experiences that align with values they've already discussed.

This hesitance can be perplexing and sometimes even distressing for advisors. If the plan demonstrates affordability, why the reluctance? As with many financial behaviors, underspending rarely comes down to the numbers alone. Instead, it reflects a complex mix of values, identity, habit, and fear. Understanding these roots is the first step – because while underspending can reflect genuine values-based contentment, at other times, it conceals barriers that keep clients from aligning their financial resources with the lives they want to live.

When Modest Living Is Values-Based

When underspending stems from values rather than barriers, it's not always a problem clients need – or want – to solve. For some, a modest lifestyle is an intentional expression of values and identity. They find meaning and satisfaction in frugality, simplicity, or generosity to others. These clients aren't denying themselves; they're aligning their spending (or lack of it) with who they want to be and who they believe they are.

For instance, a widow who grew up in a Depression-era household may take deep pride in 'never wasting a dollar'. Even if she could easily afford more, she finds comfort and identity in her consistency. Her underspending is not a sign of deprivation; it's one of congruence.

In these cases, the advisor's role is to affirm the client's alignment and ensure their plan continues to support it – not to push for more spending. Advisors don't need to change anyone's mind or persuade clients to do more just because they can. The key is discernment: Is this underspending a reflection of genuine contentment, or is it masking hesitation around unfulfilled desires?

Advisor Guilt Vs Client Reality

This discernment can be complicated by the advisor's own emotions. In our podcast series, "Relevant & Relational", Ashley Quamme and I recently discussed how advisors can have conversations with clients who could spend more, and how the discomfort with underspending can sometimes come less from the client and more from the advisor. Watching a client accumulate wealth but live 'too small' can create tension for the professional.

Advisors may think, If I had this much, I'd be traveling the world, buying a yacht, or spoiling the grandkids. Or they may wonder, Does my client think I am doing enough for them? Should I be encouraging them to have more fun? Am I earning my fee if they don't enjoy more of this money?

These projections – whether subtle or intense – can fuel guilt or frustration: They could be having more fun. Why won't they?

But that's advisor-centered, not client-centered. The first step is to pause and clarify: Whose discomfort are we addressing? Is the client genuinely expressing a longing ("I've always wanted to see Europe") or a repeated hesitation ("I'd love to give more to charity, but…")? Or is the advisor injecting their own desires, needs, or story?

This distinction between advisor-centered projections and client-centered needs matters. Pushing clients to spend when they feel satisfied risks undermining trust. Conversely, ignoring unfulfilled longings because we misinterpret them as contentment leaves clients stuck. The most effective conversations happen when advisors slow down to make this distinction explicit.

Client Barriers To Spending More

When underspending is indeed a barrier rather than a values-aligned choice, three recurring patterns often emerge.

Fear Of Future Dependence

Many clients voice some version of, "I don't want my kids to take care of me." Even in well-capitalized portfolios, the underlying fear is less about actual probability and more about dignity and independence. Clients worry that one wrong move today could jeopardize their future autonomy. Advisors usually recognize this fear, but that doesn't make it any easier to talk through. It's completely normal for clients and advisors to feel awkward talking about a future when independence may be lost. According to 2022 AARP research, many older adults fear incapacity even more than death. And if it's too uncomfortable to talk about, it gets really hard to plan for, too.

Doom Forecasting

Humans are notoriously poor forecasters of the future, and when it comes to money, we often default to catastrophe. Clients may think, If I spend now, something terrible will happen – markets will crash, I'll get sick, I'll run out. Psychologists call this "catastrophizing", a tendency to leap to the worst-case scenario. From a planning perspective, advisors tend to see the opposite: resilience in the form of a well-diversified portfolio, insurance coverage, and decades of buffer. But for the client, the imagined doom feels more real than any Monte Carlo projection.

Habit And Identity

Perhaps the most stubborn barrier is habit. A lifetime of saving builds identity: I'm a responsible saver, not a spender. Even when circumstances change – retirement achieved, children launched, goals funded – the saver identity persists. And it's not easy to move from being a 'saver' to a 'spender', even when there's stuff we really want to spend on. Spending can feel foreign, even irresponsible. Behavioral economics helps explain why: Losses hurt more than gains of the same magnitude feel good. For example, watching a portfolio drop by $30,000 after taking the family on a cruise may feel worse than the joy that was brought on by the cruise – darn Homo economicus brains!

But there's hope. Advisors who understand why clients underspend – whether it's values-based, guilt-driven, or rooted in fear and identity – are better positioned to meet clients where they are. With the right framing, they can apply the principles of behavioral finance to help clients slowly make changes. One simple approach: treat spending (or giving) not as a permanent change, but as a short-term experiment.

The Power Of Experiment Framing

Once an advisor has clarified whether the reason for underspending is values-driven contentment or a barrier to fulfillment, the next question becomes: How can clients be encouraged to act on their desires without feeling overwhelmed? This is a perfect place to reframe spending as an experiment.

By definition, an experiment is temporary, bounded, and designed to generate information. This framing reduces the stakes, lowers resistance, and allows clients to separate 'different' from 'wrong'. As Dr. Joy Lere, my colleague at Shaping Wealth, emphasizes, just because something feels different doesn't mean it's wrong. The more space we can put between "this feels different" and "different is wrong", the better.

Experimental language helps clients and advisors do exactly that. Rather than committing to a lifestyle shift, clients are simply trying something once to see how it feels. The results – positive or negative – become 'emotional data' that guide future decisions. And this matters, because research from Dr. Dan Gilbert shows that humans are poor at predicting how future experiences will make them feel; experiments generate real feedback, not guesswork.

Experiments Lower Resistance

A major fear of clients who underspend can be described as a "slippery slope". If they book one business-class flight, will that normalize luxury travel? If they upgrade the kitchen, will that spiral into constant remodeling? They worry that one splurge will lead to many more, so they avoid starting at all, fearing they won't be able to stop.

Experiment framing interrupts that fear. Instead of "You can make changes to your entire lifestyle," the conversation shifts to, "Let's try business class once. If you hate it or decide it isn't worth the money, we won't do it again."

This reframing makes the spending event finite and reversible. Clients don't have to grapple with a wholesale identity change from saver to spender; they're simply running a short-term trial. Experimental language and mindset allow judgement to be suspended until the data can be assessed.

In the conversation-framing example below, the two statements are similar in content, but tend to have a different effect on how we experience the questions in our bodies.

- Non-Experimental: "You could spend a little more on this trip. You should start flying business class – you've earned it, and you can afford it."

- Experimental: "What if we tried business class just for your next Europe trip? We can bake it into a onetime budget. If you don't enjoy it, you never have to do it again."

The second approach keeps the decision small, approachable, and free from permanence. It also generates data, which becomes invaluable for making better future decisions.

Nerd Note:

Ashley Quamme and I discuss using experimental language when talking to clients about underspending in our "Relevant & Relational" podcast mentioned earlier in this article. You can find the episode on my Substack page, (Less) Loney Money, and more conversations like it on Ashley's podcast, Planning & Beyond.

Future Self As Guide

Even when clients agree to an experiment, they often struggle to imagine enjoying the outcome. Human beings are poor 'future affect forecasters': We tend to overestimate negative outcomes and underestimate how quickly we'll adapt to positive change.

Here, advisors can invite clients to project themselves forward:

Imagine you took the trip, upgraded the seats, stayed at the Ritz for two nights, and had a wonderful time. Now, with your next trip on the horizon, would you go back to the old way?

This guided reflection helps clients bypass their forecasting bias. It gently asks whether joy, comfort, or connection is really something they'd want to undo. Most clients, when imagining a future in which they've already had the experience, realize: I probably wouldn't go back.

This reframing softens resistance and builds openness – openness that can be revisited after the fact, which makes the experimental language even more powerful.

Debrief Builds Confidence

The true power of experiment language comes after the spending trial. A follow-up meeting soon after the event allows the advisor to capture impressions while they're still fresh and unfiltered.

Questions might include:

- "What surprised you most?"

- "Which parts felt worth it; which didn't?"

- "Did anything feel uncomfortable – and if so, was that discomfort about your values or about trying something new?"

This debrief provides a structured way for clients to sort through their experience. Maybe the business-class flight felt wonderful, but the luxury hotel felt wasteful – or maybe the opposite. Either way, the conversation separates extravagance from value.

Importantly, the advisor normalizes discomfort: new spending often feels wrong simply because it's different. As Dr. Joy Lere reminds us, "different doesn't mean wrong." By helping clients articulate what they enjoyed versus what they'd skip next time, advisors equip them with confidence for future choices.

Here's an example of how an advisor can frame that debrief conversation:

Advisor: I'm curious – what did you enjoy most about that trip, and what didn't feel worth it?

Client: The nicer seats made a huge difference. But the fancy hotel… European beds are still not my bed.

Advisor: That's great data. It tells us travel upgrades may add value, while fancy hotels might not.

Rather than aiming to 'get it right' the first time, the emphasis is on building a feedback loop where clients learn, in real time, what brings joy and what feels superfluous. Over time, the cycle of trying, reflecting, and refining helps clients trust themselves – and their ability to use wealth meaningfully.

Experiment framing, in the end, reframes spending from a moral referendum into a low-stakes test. It validates fear, bypasses forecasting errors, and generates emotional data. Most importantly, it helps clients build spending confidence gradually, without feeling like they've abandoned their identity as responsible savers.

How To Implement Experiment Language In Practice

Understanding why clients underspend – and why experiment framing works – is only part of the solution. The real impact comes when advisors apply this tool intentionally within planning conversations.

Fortunately, experiment language is highly adaptable. It can be used for travel upgrades, lifestyle enhancements, charitable giving, or simply testing higher levels of everyday spending. The goal isn't to push clients toward extravagance; it's to help them gather real-world "emotional data" about what does and doesn't bring value.

Advisors can start with the four practical steps – creating, encouraging participation, debriefing, and building identity alignment – discussed below to bring experiment framing into their work.

Step 1: Create A Spending Experiment

Start by identifying a meaningful but bounded experiment, such as:

- Vacation upgrade: flying business class for one trip, staying at a nicer hotel for two nights, or booking a guided excursion.

- Lifestyle splurge: renovating the kitchen, upgrading cars sooner, or increasing discretionary cash flow for a short period.

- Charitable gift: making a onetime donation at a higher-than-usual level.

- Monthly cash-flow test: instead of spending $7,000/month, increasing spending to $20,000/month for three months and then debriefing to assess how the extra spending felt, what was fun about it, and what wasn't fun about it.

The crucial element is framing: This is just a trial. We'll try it once and then reflect. Nothing about this locks you into a new pattern.

After outlining the experiment, the advisor can reinforce it by framing it in the client's own context. For example:

You've mentioned wanting to try business class. What if we just run an experiment for your next trip—one time, no commitments beyond that—and then we'll talk afterward about how it felt?

Step 2: Encourage Full Participation

When clients agree to an experiment, they may still want to hold back – booking business class but refusing to spend more on the rest of the trip, or neglecting to spend the full budget. This temptation to hedge will only limit what they can learn.

Advisors can encourage full participation by normalizing the full range of emotions that will come up – joy, regret, or discomfort – as just data points. They aren't good or bad; they're information to use in the next decision.

I'd like you to spend the full amount we set aside for this experiment. If some of it feels uncomfortable, that's useful to know. If some of it feels joyful, that's useful too. Either way, we'll learn more than we know today.

The goal is to reinforce that any short-term pain or gain is part of the process. The real objective is to observe emotions as they arise – not to label them as right or wrong – and use them as insight into what the client likes or doesn't like.

Step 3: Debrief And Refine

The real value of the experiment comes during this stage – the debrief. Meet with clients soon after the experiment so impressions are fresh and unfiltered.

Assess their experience by asking questions like:

- "Looking back, what part of this experience would you most want to repeat?"

- "Did anything feel easier or more enjoyable than you expected?"

- "At what point did it begin to feel superfluous or hard to spend, and why do you think that happened?"

- "What do you want to do again, and what do you want to try differently next time?"

The whole goal of the debrief is to let clients share and verbalize what they've learned. The insights can shape future trips, ongoing discretionary spending, or even potential permanent changes – while keeping their overall plan in view. Because the advisor and client both have the data, any changes are easily tested in the financial plan.

Step 4: Build Identity Alignment

For many underspending clients, the challenge goes beyond fear of running out – it's rooted in identity. They see themselves as "responsible savers", and spending can feel like betrayal. If advisors ignore this, clients may nod politely but never act.

Instead, experiment language can be tied directly to identity:

Responsible people don't blindly spend; they test, reflect, and adjust. By running experiments, you're being both responsible and joyful.

Framing spending in this way allows clients to maintain continuity with their self-image while opening space for new experiences. The goal isn't for clients to replace the identity of "saver" with "spender" – but to expand it into "responsible steward who also enjoys life".

By guiding clients through these four steps of experiment language – create, participate, debrief, and align – advisors can transform underspending from a static problem to a dynamic process that helps clients explore what's possible in a safe, structured way. Each experiment lowers resistance, generates useful feedback, and reframes discomfort as a learning experience rather than a failure.

Over time, clients discover that spending can align with their values and identity without compromising their financial goals. And when advisors facilitate this process with empathy and curiosity, they don't just help clients spend more – they help them spend with confidence, purpose, and joy.

Ultimately, underspending isn't resolved with spreadsheets alone. It's addressed through empathy, curiosity, and the willingness to experiment. And by using experiment language, advisors give clients a low-risk way to test new behaviors, learn from their experiences, and build lasting confidence in aligning wealth with the values that matter most to them!

Leave a Reply