Executive Summary

As financial advisors, we see the positive impact of our work with clients. From helping them accomplish their life goals, to keeping them from the behavioral mistakes that could derail their plan, we are often in the best position to see the value of what we do. But with the rise of financial planning academics, there has also been an attempt to scientifically quantify the true impact that financial advisors have on client outcomes. Which as it turns out, is remarkably difficult to measure.

In this guest post, Derek Tharp – our Research Associate at Kitces.com, and a Ph.D. candidate in the financial planning program at Kansas State University – explores some of the research available on the use and benefits of financial advisors, and why advisors should still apply a healthy degree of skepticism when evaluating such research.

Broadly speaking, there are two branches of research on the use and benefits of financial advisors. The first includes studies like Morningstar’s Gamma and Vanguard’s Advisor Alpha which have aimed to quantify how much value advisors truly provide to their clients, which helps to both substantiate the advisor’s value to clients, and helps advisors justify how their benefits can exceed their costs. The second branch of research on the use of advisors stems from studies done within universities, often utilizing large national-survey datasets to examine questions such as who uses financial advisors, what impact advisors seem to have, and how public policy may be able to improve outcomes for consumers.

However, as it turns out, each branch of research is not without its own limitations. While industry studies have done an admirable job trying to estimate and quantify the value advisors provide, the reality is that this exercise is much harder to do than it may seem at first glance. In some cases, the “best” advice may require sacrificing financial gains for other ends (e.g., psychological comfort), which means the “best” advice could be wealth-reducing! And in any case, it is difficult to identify the appropriate benchmark that it is best to compare against in the first place (since we don’t necessarily know how the client would have acted in the absence of an advisor). Further, in some cases, such as the value that is assumed to be provided by advisors recommending low-cost investments, the reality is that not all advisors actually advise clients consistent with the assumptions of the models.

From the academic perspective, researchers often have to rely on either large data sets which may have less than ideal questions (at least to address their particular research questions). Yet in a unique study in the Financial Services Review, Heckman et al. (2017) evaluate how well questions about whether someone has used a financial planner actually measure “financial planning” as its defined by CFP Practice Standards. Unfortunately, the researchers conclude that all of the commonly used datasets have significant limitations. And while the alternative for academic researchers, which is to gather their own primary data, can help ensure that the ideal questions are utilized… these methods end up constrained to smaller-than-ideal (and potentially not representative) sample sizes.

Ultimately, the point isn’t that advisors shouldn’t follow the studies on the use and benefits of financial planning, but simply that it’s still necessary to apply a healthy degree of skepticism when reviewing and applying research. Although with the ongoing rise of financial planning academics, more and better opportunities are coming for advisors and academics to collaborate, bringing together best practices in research from academia with the practitioner’s real-world understanding of financial planning and how it is delivered to clients!

The Increasing Amount Of Research On The Use And Benefits Of Financial Advisors

An increasing amount of research is being conducted on the use financial advisors and the benefits of doing so.

For obvious reasons, this research is of interest to many. Consumers want to understand how and when it makes sense to work with a financial advisor; regulators and public policymakers are interested in the role that financial advisors play in helping consumers achieve financial wellbeing; and, of course, financial advisors themselves are highly interested in knowing both how they can deliver value to their clients and how they can tangibly convey that value to clients and prospective clients.

Given the rise of financial planning academics, more and more researchers are increasingly available to investigate such questions. As a result, advisors should expect to see more studies evaluating the use of financial advisors in the future.

But this also raises an interesting question: How much trust should we place in these studies in the first place?

The Two Tracks Of Research On The Use Of Financial Advisors

Quantifying The Value Of Advice

There are at least two broad tracks of research on the use of financial planners. The first is a series of studies which have tried to quantify the actual value of advice that a financial advisor provides. These have included white papers and analyses typically conducted by firms within the industry.

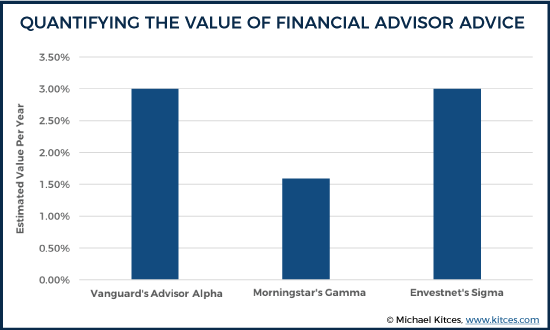

The most well-known articles in this area include Morningstar’s Alpha, Beta, and now…Gamma (Blanchett & Kaplan, 2013), Vanguard’s Advisor’s Alpha (Kinniry Jr., Jaconetti, DiJoseph, Zilbering, & Bennyhoff, 2016), and Envestnet’s Capital Sigma (Envestnet | PMC’s Quantitative Research Group, 2016) – all of which have previously been reviewed in The 2015 Volume 3 of The Kitces Report.

In short, these papers have concluded that financial advisors can deliver significant value to consumers, ranging from 1.59% per year for retirees (Morningstar) to 3.0% per year or more (Vanguard and Envestnet), through the use of strategies such as rebalancing, asset location, retirement withdrawal sequencing, and behavioral coaching.

Consumer Behavior, Decision-Making, and Wellbeing

The second track of research has been more academically-oriented, typically analyzing both the use of financial advisors and their impact, and is usually in the form of studies done by scholars who typically publish in peer-reviewed journals. While it is harder to generalize this body of research, these studies could be broadly said to investigate how the use of a financial advisor relates to consumer behavior, decision-making, and/or a consumer’s (hopefully improved) wellbeing.

Most financial advisors will be less familiar with this body of research, as occasionally such articles are seen in more practitioner-oriented publications such as the Journal of Financial Planning, but more often they are released in academically-oriented publications such as the Journal of Financial Therapy, Journal of Personal Finance, and Financial Services Review.

Typically, these academic studies are either based on clinical experiments or secondary analyses of large, nationally-representative datasets.

Healthy Skepticism Of Financial Planning Research

The increasing prevalence of academic research (and hopefully engagement between academics and practitioners!) warrants a general word of caution that we should always view research with a healthy degree of skepticism.

Do note the qualifier here – healthy – as it is easy to wind up too far on either side of the skepticism spectrum. The radical skeptic who distrusts all research is bound to miss insights that could have helped them build a better business or provide more value to their clients. By contrast, the stark anti-skeptic will inevitably be led astray by their undoubting trust in research – making a poor decision due to placing too much faith in underpowered, ungeneralizable, or sometimes outright biased studies.

As an example of just how hard finding the right balance can be, consider Daniel Kahneman’s 2017 response to a blog post criticizing some of his chapter on priming in “Thinking, Fast and Slow”. In his response, Kahneman did something we almost never see researchers do (and certainly not researchers of Nobel laurate stature) – he made a difficult though intellectually admirable confession:

What the blog gets absolutely right is that I placed too much faith in underpowered studies. As pointed out in the blog, and earlier by Andrew Gelman, there is a special irony in my mistake because the first paper that Amos Tversky and I published was about the belief in the “law of small numbers,” which allows researchers to trust the results of underpowered studies with unreasonably small samples.

If one of the world’s most well-respected social scientists can fail to apply a healthy degree of skepticism towards research, it is likely that most of us can err in this way too.

Can We Trust The Research On Quantifying The Value Of Advice?

In the spirit of applying a healthy degree of skepticism, it is worth noting a few things about the different types of research related to the use of financial advisors.

As was covered extensively in The 2015 Volume 3 of The Kitces Report, there are several complications with trying to quantify the value of advice that advisors provide. First, it is often very difficult to measure the value that a strategy provides. Consider the following example:

Example 1. Suppose Strategies A and B both provide a nearly certain probability of success, but Strategy A maximizes wealth, whereas Strategy B actually sacrifices some wealth for the sake of maximizing psychological comfort.

As soon as we allow financial advisors to give advice aimed towards any objective other than maximizing wealth (as we should, because a client’s goal may not be to maximize wealth!), the difficulties inherent to quantifying the value of advice become apparent. We can’t merely use wealth to define which strategy is best, because, given a client’s goals and preferences, the “best” strategy may actually require reducing wealth (in pursuit of psychological or other trade-offs).

So how do we value non-financial psychological wellbeing (what economists often refer to as ‘psychic income’)? What’s the price of peace of mind?

In reality, financial planning requires a balancing of both the financial and non-financial considerations. It’s not all about money to the exclusion of all else, but you can’t eat happy thoughts, either. But once we acknowledge that both financial and non-financial considerations matter, it’s a whole lot messier to try and quantify the value of advice.

To their credit, the authors of each of the previously referenced articles seem aware of such limitations. Each does carefully consider how “value” should be measured: Vanguard focuses on absolute wealth, Envestnet looks at risk-adjusted return improvements, and Morningstar examines improvements in economic utility of an outcome. But the reality remains – no matter which framework we use, we can never perfectly capture everything. And the mere fact that each study uses a different way of measuring the value of financial advice just emphasizes the challenge further!

Another difficulty is what has been referred to as the “compared to what” problem. When we try to determine whether an advisor’s advice actually improved an outcome, we need to have a benchmark to compare against – what would have happened if the advisor had not delivered the advice that was given? Yet while we can make some educated guesses to try and figure this out, we can never actually know what would have happened.

Of course, we know that inertia is powerful and that many people fail to take action, and thus might assume the client would have done what they were doing before and made no changes. But we can’t be certain of this. Perhaps the psychological discomfort that led the client to seek out a financial advisor would have eventually spurred him/her into action anyway? Perhaps he/she would have read a John Bogle book (or similar wisdom), and the previously poor saver would have become the avid saver – maybe even better than they would have become with the help of a financial advisor? Or perhaps not. But that’s the difficulty. We can never know.

Advisor Cost-Saving Fallacy: Do Advisors Really Reduce Investing Costs For (All) Clients?

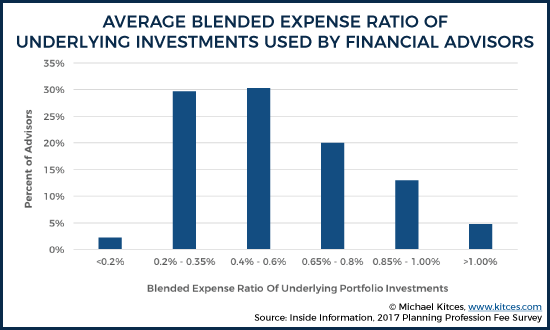

An example of one of the easier “compared to what” problems with the existing studies is the assumption regarding advisor use of lower cost investments. In Vanguard’s analysis, an investor with an all-stock portfolio is assumed to pay an “average” expense ratio of roughly 0.55% versus the low-cost ETF portfolio an advisor is assumed to recommend at 0.15%. These savings alone generate roughly 40 basis points of “Advisor Alpha”, which amounts to over 13% of the total Advisor Alpha found in Vanguard’s study (Envestnet used similar assumptions to attribute 82bps of value to the advisor).

Of course, these assumptions don’t actually hold in all circumstances. What if the investor already had a low-cost portfolio, such that this cost saving was a moot point? Or alternatively, based on data from Bob Veres’ recent survey of all-in financial advisor costs, only 2% of financial advisors actually recommend portfolios with expense ratios of the underlying investments coming in at <0.2%. The median blended fee of underlying investments actually reported by financial advisors was 0.50%, with 38% reporting fees above 0.65%. In other words, Vanguard and Envestnet’s assumed advisor recommendations – that directly generate value attributed to an advisor – look nothing like what most advisors actually recommend! Thus, while Vanguard reports 40bps of Advisor Alpha derived from reducing the expense ratios of a roughly 55bps portfolio, survey data on advisor-recommended investments suggests the actual cost is close to 55bps, implying that median advisor is actually generating virtually no cost-savings Advisor Alpha… and close to one-half of advisors are generating negative cost-savings Advisor Alpha (using Vanguard’s research approach)!

In turn, though, this conclusion also ignores the possibility that the investments being recommended by those advisors themselves add value, and presumably at least some of those advisors genuinely believe that the added costs provide some additional value to the client. Which means cost alone may not tell the whole story… but, again, that makes it very difficult to figure out what the true Advisor Alpha really is.

Nonetheless, the key point remains: the Advisor Alpha determined by the Vanguard study is predicated on recommendations that don’t appear to bear much resemblance to what most advisors actually recommend. (And other studies that purport to measure the value of financial advisors face similar problems.)

And these distinctions matter, because in the aggregate they can actually undermine much of the existing value currently attributed to financial advisors! For instance, suppose a prospect comes to an advisor with a well-diversified ETF portfolio with a blended expense ratio of 0.10%. Additionally, assume the advisor recommends a portfolio with an expense of 0.75%. If the client is hesitant to pay the advisor's fee, it really isn’t accurate for the advisor to point to the Vanguard paper and claim that advisors provide 3.00% of value. Whereas the Vanguard paper assumes an advisor’s portfolio recommendations would generate 0.40% of Advisor Alpha, the actual underlying facts suggest the investment selection portion of Advisor Alpha, according to Vanguard’s methodology, would be -0.20%. This one difference single-handedly swings the advisor value from 3.00% to 2.40%, which is a meaningful difference given that Vanguard’s assessment was before an advisor’s fees and the true value that a client receives would need to be reduced even further.

Fortunately for advisors, as was discussed previously, there is a lot of non-financial benefit that is either not being quantified in these types of analyses, or may actually be wealth diminishing (but desirable for the client anyway). In the end, such benefits, combined with the financially measurable ones, may well be large enough that the advisors are easily delivering more value than their cost. But it is still important to note that studies of the value of financial advisors do have considerable limitations. Namely, advisors should be careful assuming that the assumptions of the study necessarily apply to themselves or to a given prospect. Quantifying the true value that an advisor adds must actually be based on a valid comparison, and often these are nearly impossible to come by because we can never know what actually would have happened in the future.

Consumer Behavior, Decision Making, and Wellbeing

From an advisor’s perspective, it is also important to carefully consider the application of more academically-oriented research on the use of financial advisors and how it impacts consumer behavior, decision-making, and financial wellbeing.

Within this branch of research, there are two more subcategories, each with their own unique limitations.

Clinical Research On The Use Of Financial Advisors

The first is clinical research. As has been noted previously on this blog, this is the type of research that will drive the financial planning industry forward, by actually testing which types of financial advisor interventions really improve client outcomes (rather than just assuming the client’s situation, the advisor’s recommendations, and how the latter will impact the former).

A good example of a clinical study like this is the 2016 study in the Journal of Financial Therapy titled “Promoting Savings at Tax Time through a Video-Based Solution-Focused Brief Coaching Intervention”. In this study, Palmer, Pichot, and Kunovskaya investigated the impact of a video-based solution-focused brief coaching intervention provided to 212 individuals receiving tax preparation services at a Volunteer Income Tax Assistance location. The researchers found that the coaching provided was successful in increasing both the frequency and the amount of self-reported savings at tax time.

Yet a practical limitation of such studies is that the sample sizes are often very small. Which makes Kahneman’s self-criticism for putting too much faith in small sample studies is especially germane. As while small sample studies play a crucial role in the development of scientific knowledge – often they are an important first step to larger scale projects investigating the same phenomena – they do have considerable limitations.

First, the small sample nature of these studies simply means that there is an increased chance the findings were the result of random chance. This is why researchers prefer larger samples, all else being equal, as it reduces the risk that random chance materially impacts the outcomes.

Another concern is what is known as the ‘publication bias’ or the ‘file drawer effect’. This refers to the fact that many of the incentives in academia and journal publishing more generally lead researchers to never publish studies which find no statistically significant or interesting findings. As a result, a disproportionate number of studies with spurious findings or questionable research methods end up getting published (just because their results were statistically significant), while studies which rigorously test an intervention and find it to not be significant just remain unpublished in the file drawers of academics.

Additionally, small sample studies have the problem of usually being non-generalizable. In other words, the sample size could be so small and unique, that what worked in the study might not actually work for the broader advisor-client population. This is the reason researchers love nationally representative studies, as the findings from such studies can subsequently be generalized to a very large population. But this is almost never the case for small studies unless the advisor’s clientele really does match the particular type of subjects that were tested in the study.

For instance, suppose a new study from a financial planning academic at a university is released which finds some very intriguing results about the design of a financial advisor’s office and client satisfaction. Further suppose that the study was conducted entirely with students from a college campus (a common pool of participants for this type of research, for obvious reasons). If you specialize in working with high-net-worth doctors, would you want to run out and redesign your office immediately based on this research? What if your typical client was a blue-collar worker making a pension rollover decision? Perhaps not, because it is not clear whether the findings would generalize from the sample population (college students) to your particular target clientele (high-net-worth doctors, or blue-collar workers preparing for retirement). Fortunately, not all research is so narrow that it faces such constraints, but the point remains that it's necessary to be careful taking small sample findings and putting them into practice.

Of course, as entrepreneurs, there’s nothing wrong with experimenting, and those who put innovative methods into practice first can actually reap the rewards of doing so. Entrepreneurs don’t operate in the highly exacting world of academia. They’re out in the thick of the real world, trying to learn from trial and error. So the point here is certainly not to suggest that it’s never worthwhile to follow and engage in this emerging research literature, but instead, to simply acknowledge that you shouldn’t go too far in the other direction and treat research as gospel.

Secondary Analyses Of Large Datasets

The second strand of academic research that advisors want to carefully draw conclusions from are quantitative analyses based on large datasets, where a survey has already been distributed to a large group of people, and the researchers try to come up with research questions that might be tested and evaluated using the available data.

For instance, studies have investigated topics such as the characteristics of those who seek financial advice and the predisposition of women to use the services of a financial planner for saving and investing. In the former, Alyousif and Kalenkoski analyzed data from the 2012 National Financial Capability Survey (NFCS) and found that financial fragility and low subjective financial knowledge were associated with lower likelihood of seeking financial advice. In the latter, Evans analyzed data from the 2004 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) and found that households where the financially most knowledgeable spouse was female were more likely to use a financial planner for assistance with saving and investment decisions.

Unlike the small sample size problems of clinical research, studies based on nationally-representative data present much lower risk that findings will simply be due to random noise. These studies have much more statistical power, but they still have their own set of limitations.

Unlike clinical studies, which often develop their own research questions and can be very precise in how they aim to measure their variables of interest, researchers conducting secondary data analysis are relying on survey questions written by someone else and then delivered to a large number of individuals. This type of research can present considerable concern related to the reliability (the degree to which a measure will produce stable results) and validity (the degree to which a measure is actually measuring what we want to measure) of research findings.

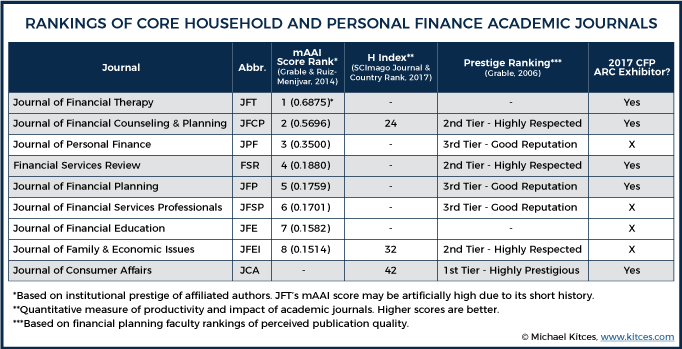

Specifically related to the analysis of the use of financial advisors, Heckman, Seay, Kim, and Letkiewicz (2016) recently published a paper in the Financial Services Review examining the measurement of the use of financial advisors amongst different datasets commonly used within financial planning research.

Heckman et al. identify seven different national datasets that have been used to investigate questions related to the use of a financial planner. These datasets include the: Asset and Health Dynamics among the Oldest Old (AHEAD), American Life Panel (ALP), Health and Retirement Study (HRS), National Financial Capability Survey (NFCS), National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79), National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 (NLSY97), and Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF).

Using the CFP Practice Standards to provide a definition of financial planning, the researchers assessed the degree to which questions about the use of a financial planner within these surveys actually provide valid and reliable measures of financial planner use. Specifically, the authors identify that a valid measure of financial planner use should:

- Provide a clear identification of the professional involved (i.e., broker, banker, etc.)

- Determine whether the actual financial planning process is being followed

- Determine whether planners assess life goals in the process

- Address the management of one’s resources

- Cover multiple financial planning topic areas

- Identify specific financial planning areas covered

- Assess the client’s intent to engage a financial planner

- Assess the thoroughness of data gathering

- Assess the depth and breadth of recommendations

Unfortunately, using these criteria to determine whether financial planning is actually being measured, the researchers find that there are considerable concerns about validity amongst most measures.

For instance, the National Financial Capability Study (NFCS), conducted by the FINRA Investor Education Foundation, is a survey widely used by researchers because it includes a large number of participants (~500 from each state and D.C.) and has many useful financial measures. However, when assessing how well the study actually measures financial planner use, the researchers determined that the NFCS falls short.

The NFCS asks respondents:

“In the last 5 years, have you asked for any advice from a financial professional about any of the following?”

Respondents then answer “Yes”, “No”, “Don’t know”, or “Prefer not to say” to each of the following categories:

- Debt counseling

- Savings or investments

- Taking out a mortgage or a loan

- Insurance of any type

- Tax planning

Accordingly, researchers then analyze what the impact is of “having a financial advisor” by looking at the differences in other factors (e.g., wealth, income, life satisfaction, and other metrics) between those who answered “Yes” (i.e., “uses a financial professional”) versus those who answer “No” (i.e., “don’t use a financial professional”).

Except utilizing the criteria the researchers developed from CFP Board Standards, we can take a look at how well these questions actually address whether someone used a financial planner. In assessing these particular questions, the researchers determined:

- Does the measure provide a clear identification of the professional involved (i.e., broker, banker, etc.)? No

- Does the measure assess whether the actual financial planning process is being followed? No

- Does the measure determine whether planners assess life goals in the process? No

- Does the measure address the management of one’s resources? No

- Does the measure cover multiple financial planning topic areas? Yes

- Does the measure identify specific financial planning areas covered? Yes (debt counseling, savings/investments, mortgages, insurance, or tax planning)

- Does the measure assess the client’s intent to engage a financial planner? No

- Does the measure assess the thoroughness of data gathering? No

- Does the measure assess the depth and breadth of recommendations? No

So, out of the nine criteria identified by the researchers, they found that the NFCS measure only fulfilled two. In other words, it’s not really clear how many people who say “Yes” to the question are really using a true financial planner, receiving a comprehensive financial plan, or are actually going through a formal financial planning process.

Similarly, when this process is repeated for all of the data sets mentioned previously (see Table 2), the researchers found that, at best, the commonly used measures to assess the benefits of “using a financial advisor” only fulfill 4 to 5 criteria of whether the consumer is actually engaging a financial advisor. And even then, some of those have to be implied.

Now, this probably shouldn’t be too surprising of a finding to most practitioners. Imagine you meet with 100 prospects and ask them if they currently work with a financial planner/advisor? Do you suppose their answers would generally yield the type of responses that support high-quality research about the use of financial planners? How many will say “Yes, I have a financial advisor” based on the insurance agent who once sold them life insurance years ago, or a mortgage broker who helped them buy their house, or a retail representative at a local bank branch who recently helped them roll over a 401(k) (but provided no further advice)?

The researchers ultimately conclude that studies based on the SCF and NLSY79 have the most promising measures, but even those have significant limitations – namely, that we often don’t know specifically what type of advisor somebody met with or how frequently they met with that individual. In other words, whether there was actually an ongoing financial planning relationship, or whether someone just happened to meet with a financial advisor once?

Broadly speaking, the datasets that Heckman et al. identified are very good datasets, but the concern is that the measures related to the use of financial advisors may not be. So, we want to be careful not to accept findings that merely appear “scientific”, if the underlying measures don’t actually evaluate the use of financial advisors in a manner that is really valid.

Fortunately, there’s good reason to be optimistic about the future of secondary analysis related to the use of financial advisors. Just like psychologists develop better-and-better measures over time which eventually get integrated into national datasets, financial planning researchers are in the process of doing that now. Our field is much younger and smaller than psychology, so it will take some time, but the growing number of researchers means that we are moving in the right direction!

How Should A Practicing Financial Advisor Evaluate Research?

So how should a practicing financial advisor who wants to engage in the research literature do so?

There are several key takeaways for practitioners. First, apply a healthy degree of skepticism to any findings you come across. This doesn’t mean to ignore the research, but don’t accept it uncritically either. Does the research actually apply to your practice? Is what the researchers are trying to measure actually what is useful to you? Were the individuals studied actually the types of clients you work with?

Your own gut check as a professional can be important here. Of course, sometimes research findings are completely counterintuitive and our gut will mislead us, but often financial planning professionals who engage with clients on a daily basis are actually equally if not better equipped to assess the ‘face validity’ (i.e., whether a measure is actually capturing what the researchers intend for it to capture) of various research constructs.

One of the healthiest effects of the continued comingling of researchers and academics is the ways that each side can learn from one another. For instance, at a conference last year there was an academic addressing an audience of professionals and reflecting on how, through an in-class assignment, the instructor (and the students) learned how difficult data gathering was. To an academic who hasn’t practiced professionally and has generally had all of the pertinent financial planning facts handed to them upfront within a case study, it’s reasonable to understand how this can get overlooked. As a result, it’s not hard to imagine how a well-intentioned researcher could develop a research question which misses some key aspect of data gathering in practice.

Thus, the professional, steeped in the difficulties and real-world limitations of trying to get data from clients, may have some important insights regarding the relevance of research. So, if your gut is telling you something is off with a study, don’t ignore it.

But, at the same time, be open to challenging your preconceived notions. Don’t assume that there isn’t more to be learned, or that conventional wisdom can’t be widely misled. Try your best to adopt insights from research prudently. Update your views in light of the weight of the evidence in question. Be skeptical, but find balance in developing a healthy degree of skepticism. Then, in your role as an entrepreneur, take ideas out in the market and test them. And, as you learn, don’t be afraid to communicate with academics. In the end, a healthy flow of information is what both researchers and practitioners need to thrive.

So what do you think? Can advisors trust the research on the use of financial planners? How do you quantify the value of advice? How do you decide when to incorporate research findings into your own practice? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Great review of the literature and studies available, Derek. From a building the literature perspective, the closer researchers can get to lab-type (clinical) studies related to the use of advisors, the better. Field studies in large organizations might serve as a great source of testing out some of these research questions, even if they’re not controlled as much as we would like in a lab setting. For example, researchers could examine key financial outcomes of employees working with advisors as part of an overall financial wellness program versus employees in a financial wellness programs without advisor help. The type of advice, frequency of contact, specific recommendations, etc. could be controlled to some extent. And, of course, there’s lots to control from an individual differences perspective (motivation, desire to work with an advisor, financial acumen, etc.), but it’s another way to examine advisor value. Thanks for this great review.

Great article! Just wondering if there’s a typo? …don’t have the white papers in front of me but by memory I thought vanguard put forward the 3% value and morningstar was the 1.59% (getting down to the hundredth is a remarkable feat!)

Good catch, Chris! The post has been updated. Thank you for pointing that out.

The article is spelled out logically; makes sense. The first thing that comes to my mind is, no matter the study or type of approach, what is being measured is the middle of advisor effectiveness. In each study, it assumes that all advisors behave the same. Which is not true.

There is a wide range of competency in this business. So, a range of outcomes for these studies might be a better way to capture the inner 80%.

For example, someone with significant stock options will likely be better served with a stock option/planning specialist than an advisor in the middle. A business owner exiting their business will likely get better results, quantitatively or qualitatively, with someone who specializes (by quality of work, not just designation) in business exit planning.

In our world where we specialize in an asset class that is highly concentrated and directly-held, a simple shift in strategy can create millions of dollars of positive change. Whereas many other advisors may walk by this asset type.

Something to think about. something i would not know how to quantify.

Hi Derek and Michael

Great review.

It is also a great thing that the profession is moving toward testing the efficacy of personal financial planning and the value of financial planning.

My definition of a fair fee is one that is willingly paid and accepted with neither party losing gratitude. Since the planning process is pro-spective and preventive, measuring the success (value) will have some intangibles (peace of mind).

Other areas of value can be finding error in tax returns (when reviewing) and getting the client a refund. Or the multiyear tax savings created through deflecting income to lower tax brackets and investing the tax savings over 20 to 30 year period of time.

Other “value” could be getting clients to buy disability insurance (lifetime benefit) and 20 years later the client is disabled and now enjoys replacement income along with medical issues. Of course, not everyone gets to be disabled and collect benefits.

Likewise the benefit of planning and sustaining the plans sometimes reveal the value many years later (a case in point might be asset protection).

Curious whether existing practitioners could be surveyed to discover the many ways their clients have expressed appreciation or recognition that without the planning process they would have not been able to “?”.

Or show other client situations where the value for planning (not just investing) was delivered. Curious too, if client surveys and self-report could provide statistically significant data.

Thanks for publishing this very important conversation.

Neal

What a great topic. My opinion is the following: The best client relationships start with shared values. This is the most critical factor.

Most all financial planners are compensated by AUM and or commissions. These would be classified as the hard side of the relationship. Metrics on this side of the fence are not what sustains a longtime relationship. The soft side of the relationship addresses family council, governance, family mission, personal goals, leadership as well as many other matters that can be summed up as 5 critical areas. They are family preservation, asset protection, family celebration, family legacy, and educating future successors,

matters of this importance are learned over a long period of time. This is where for the adviser wisdom is learned and applied.

Those clients that stick with the relationship more than likely share the same values with the adviser. Hence producing a long-term relationship. This is the side of the fence that drives the relationship successfully. Can you measure it? Maybe. In the end an adviser relationship with a client depends on much more than stock market returns. Market returns are and always will be volatile. A shared value relationship is not. Once an adviser has achieved a reasonable level of life transition experience and has applied that wisdom to their client base when appropriate will serve as the anchor for a long successful relationship.

In the end, we are dealing with people. Real human emotion is what every adviser needs to experience and learn from in order to be successful in this business.

I like to compare a mother bear that stands behind her cubs and every now and then she lets them know that the path they are taking is the wrong one. It is more than likely in a way that the cubs think they figured it out. This is where the wisdom comes in. It’s all about how you say it, when you say it and then demonstrating to the client that they would have figured it out on their own.

Tough to measure the value of this for sure. Yet, these behaviors are what wins the day. One thing I do know is that you will not be successful with hard side issues unless the soft side issues are addressed first.

The very best advisers I know are very adept at these skill sets that I have mentioned.