Executive Summary

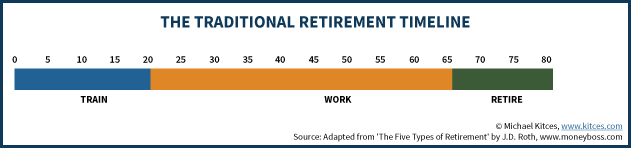

The 'traditional' approach to retirement is relatively straightforward: save and invest as much as you can, for as long as you can, starting as early as you can, to accumulate enough retirement savings that you no longer need to work, and instead can enjoy a life of leisure. For those who struggle to save, Social Security provides some retirement safety net, and for everyone else, the more and faster you save, the earlier you can retire and the more leisure time there may be.

The problem, however, is that a growing base of retirement research finds that fewer and fewer people actually want a retirement of all leisure and no work. Thanks in large part to our “hedonic adaptation” abilities – where we quickly adjust to our new circumstances – retirement is actually boring for many! Barely half of today’s retirees state that they never intend to work again, and barely 1/3 of pre-retirees have an intention to make retirement a period of not working indefinitely. Instead, whether it’s part-time work, entrepreneurialism, an encore career, or some other path, “retirement” is less and less about not working at all, and more and more about finding a different kind of engagement (which may still involve a non-trivial amount of employment income).

The significance of these changes is that if an intense period of work followed by an extended period of leisure turns out not to be the ideal approach retirement – and that instead, better alternatives might be an extended period of “semi-retirement” (with part-time work) or a series of “temporary retirements” (interspersed with sabbaticals and then new careers) – that the traditional retirement savings approach might not make sense either.

Because the reality is that if retirement is really more about doing different and perhaps more fulfilling (but not necessarily zero-income) work, then it really might not take nearly as much to “retire” as commonly assumed. And “retirement” portfolios themselves might look very different, if their primary purpose is to be a buffer for retirement transitions and perhaps scaled-back work, rather than a period of earning nothing at all. Some actually necessitate more savings, but have a smaller average balance (as it's built up and spent), while other types of retirement would actually allow for less ongoing savings and smaller retirement account balances (supplemented by partial work in "semi-retirement" that could last for years or decades).

In turn, a future with different types of retirement could also increase demand for disability insurance (as a greater reliance on the ability to work and earn income puts us at even greater risk if that goes away), and increase the need for emergency savings (for more extended mid-career transitions). Though from the financial advisor’s perspective, perhaps the greatest potential disruption of different types of retirement is that for most of the alternatives to the “traditional” approach, retirees will never accumulate as large of a retirement portfolio in the first place, which could substantially impair the feasibility of the AUM-based retirement planning approach!

Traditional Retirement – From Unworkable Time To Leisure Time

For most of human history, “work” was something we did for survival, as long as we were physically capable. In the “modern” era, we at least instituted a process of schooling when we were young – if only to train for more sophisticated work to do, for the rest of our lives. Of course, the caveat is that the longer we live (thanks in part to improving health and medicine), the more likely it is we’ll reach a phase in our lives where we physically (or mentally) can’t work anymore. Thus, in 1889, Germany instituted the first “old age social insurance program” – a predecessor for our Social Security program in the US – to provide a means of taking care of those who no longer could work to provide for themselves. Of course, back then, few were expected to actually rely on the program; the initial retirement pension began at age 70, when the life expectancy of a Prussian was only 45!

Yet continued medical advances over the past century have fundamentally shifted retirement, from a period of “worker’s obsolescence” (where forced retirement was a way to get older, less productive workers out of the way for younger, newer ones) into a world where retirement itself lasts so long that it’s actually a “phase of life” – a post-work period of planned leisure, the culmination of a lifetime of working and saving.

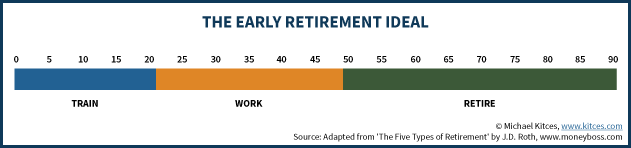

As retirement shifted from a period of obsolescence to one of leisure, it is not surprising that many wanted to maximize the leisure time – which to some extent elongated naturally with continued health improvements, but also has driven a focus on trying to retire “early” in order to have more leisure years to enjoy. Of course, the caveat is that retiring earlier means it’s necessary to save more in order to retire (since there are more retirement years to pay for), which in turn may entail trade-offs of spending less today (for current workers). Accordingly, the reigning paradigm became “save as much as you can, for as long as you can, and you’ll be able to retire as early as possible (and enjoy as long of a retirement as you can!)!”

The Hedonic Treadmill Of Leisure Time

For those who are working – particularly in a job they don’t enjoy – the idea of an extended retirement of leisure sounds like a highly appealing goal to reach. The problem, however, is that not everyone seems to enjoy it once they arrive.

The problem is that human beings are remarkably adaptable to their circumstances, and our happiness tends to revert to a relatively stable level, even after major changes and life events. The phenomenon, known as “hedonic adaptation”, means that while we’re working, a life of leisure sounds great… but once we actually retire into that life of leisure, it often becomes boring and routine and no longer as enjoyable. In other words, we may continue walking towards a goal that we perceive will bring us happiness, but like being on a (hedonic) treadmill, no matter how long we walk, we never actually make much progress forward.

As a result, a growing number of retirees are seeking ways to stay active even after retirement – developing, in the words of Mitch Anthony, a “New Retirementality” about what retirement really means, that goes beyond just living an “active leisure” lifestyle. From the rise of “Encore Careers”, to growing entrepreneurialism amongst “seniors” over age 65, a recent Age Wave study found that in reality only about half of retirees actually plan to “not work” in retirement! And the trend is accelerating – the same study found that amongst pre-retirees, only 28% actually plan to “never work for pay again” in retirement (and amongst those, some will likely simply “work” as a volunteer instead)!

In other words, the transition to “retirement” might at least mean retiring away from a current job or career – particularly if it’s not a very enjoyable one – but doesn’t necessarily mean retiring from work altogether. Which is important, from the perspective of the modern focus on saving (early and aggressively) for retirement!

3 Different Types Of “Retirement”?

If you assume, for a moment, that reaching the moment of “retirement” doesn’t actually mean the end of work, but merely the end of a current job or career – opening the door to a new type of work instead (and, potentially, one where it matters less how much you make) – what you end up with what J.D. Roth calls several different “types” of retirement.

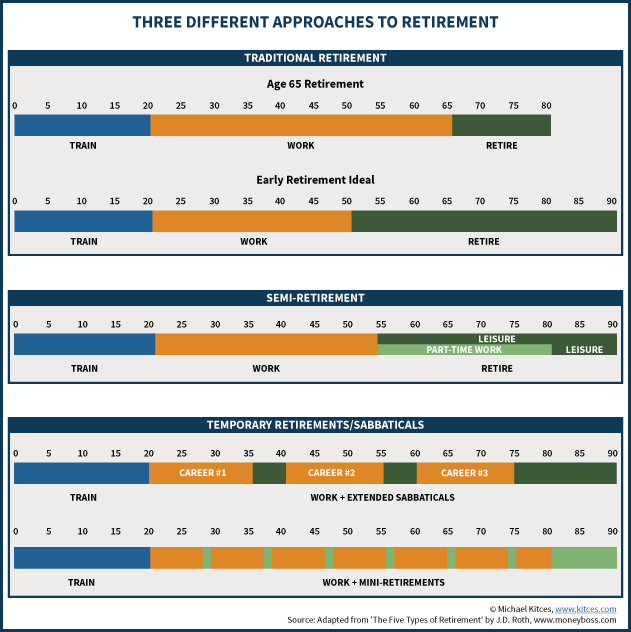

The “traditional” type of retirement is the one that we’re all most familiar with – save early and often, invest prudently for growth, and retire as soon as you’re financially able. If you can grow your retirement portfolio fast enough, you can retire early. If not, you’ll at least have the opportunity to retire in your 60s when Social Security becomes available. The time in retirement is filled with leisure, or perhaps engagement through volunteer “work” (but without any financial remuneration).

One alternative, though, is a form of “semi-retirement”, where work is scaled back, but not eliminated. This might entail starting a business, pursuing a new career, or engaging in consulting or part-time work in a prior career. In essence, semi-retirement in this context means retirement from the current full-time job/work, but not necessarily from any work. In fact, some level of ongoing – and paid – work would be anticipated, which helps both personal fulfillment and wellbeing, and provides substantial ongoing financial assistance (which in turn means it may be able to happen earlier than traditional retirement)!

The third type of retirement is engaging in a series of “temporary retirement(s)” – in essence, sabbatical breaks that occur, with some planned regularity/periodicity, for a limited period of time, after which the individual returns to the working world (albeit in a potentially new job or career track). In this approach to “retirement”, the act of retiring – withdrawing from the working world – is not something that comes at the end, but instead is dispersed more regularly throughout the individual’s productive years, perhaps as transitions between extended careers. Depending on the individual’s inclination (or type of work, or chosen profession), the pace of sabbaticals could be less frequent but for longer periods of time, or for shorter periods that occur more often. The phase of retirement at the end would be shortened though, as those retirement years are intentionally “redistributed” into earlier phases of life.

Saving For Different Types Of Retirement?

The reason why these different types of retirement are so important is that the “standard” saving for retirement approach is really only effective for one type: the traditional one (either at ‘normal’ retirement age, or earlier retirement). Because in most other forms of retirement, that won’t have such an extended period of “no work” (and no income), it’s simply not as necessary to generate a huge pile of retirement dollars in the first place!

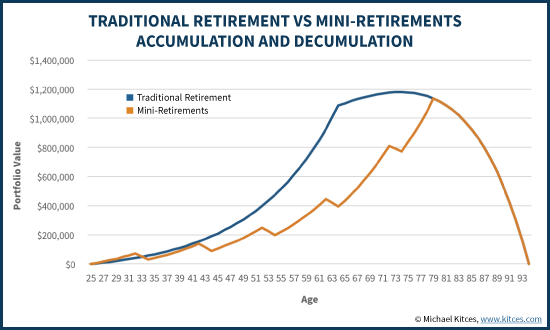

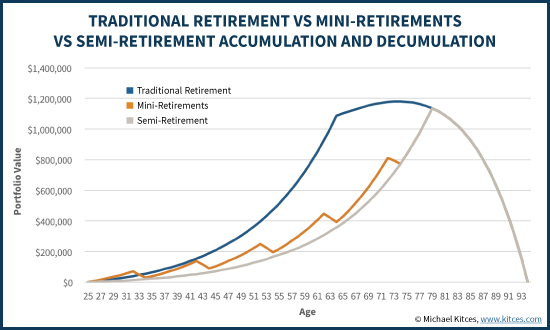

For instance, if leisure periods are going to be shorter and temporary, followed by a return to work (which continues to a later age), then the reality is that for most of your life, you never need as much in retirement savings, as it only peaks at the very end to cover the last decade when some sort of work is no longer feasible!

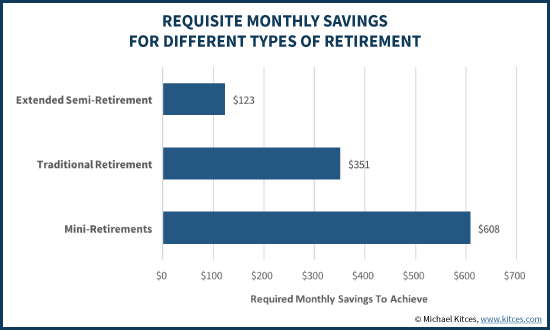

As shown above, with a series of ongoing temporary retirements (or sabbaticals), the retirement savings account never quite accumulates as high, and doesn't need to be accumulated nearly as rapidly, because the retirement phases just aren’t that long! On the other hand, it’s notable that with shorter ramp-ups and faster spend-downs, the portfolio never has as much time to grow and compound, nor will it be invested as aggressively (given the shorter time horizons), which means the prospective (ongoing-temporary) retiree will need to spend less and save more to make the balance work. In this case, the retiree had to increase savings for $350/month to about $600/month to maintain the same standard of living. Yet ultimately, that’s simply a trade-off decision to consider when choosing the ideal type of retirement.

Similarly, someone who chooses to engage in semi-retirement – and continues to partially work while being financially independent – also drastically reduces the required savings to “retire” for most of their lifetime. Because human capital – the present value of future earnings from continued work – is actually worth a lot as a “retirement” asset!

After all, at a 4% safe withdrawal rate, generating $40,000/year of income for several decades of leisure requires $1,000,000 of retirement savings. Which means someone who’s willing to continue doing at least some work in retirement could substantially defray the required savings. Every $10,000/year of work in a state of “semi-retirement” financial independence reduces retirement savings needed by $250,000! “Just” earning $20,000/year to supplement a $40,000/year withdrawal goal cuts the required retirement savings by half a million dollars.

Notably, in the semi-retirement scenario above (where it is assumed that the retiree works part-time to cover household expenses from age 55 to 80), there may still ultimately be a final period without any work at all, but again, it tends to be much shorter in duration and occurs later; in this context, retirement savings is less about a period of "leisure" and more about just covering the final decade when work fully stops! But the fact that the portfolio itself has longer to grow also drastically reduces the required retirement savings; in the semi-retirement scenario, "success" requires only about $120/month of savings, or nearly 2/3rds less than the traditional retirement!

And notably, the key point here is not merely that these alternative paths to retirement may entail different retirement savings strategies, but specifically that alternative forms of retirement may require far more in ongoing monthly retirement savings, or far less, depending on the type of retirement – and either way, most will have a much smaller retirement account balance for most of their lifetimes. In the context of today's prospective retirees in particular, for those who may be able to engage in "semi-retirement" and still partially work, the results suggest that many may be unnecessarily stressing about their ability to save for a “retirement” that won’t actually necessitate nearly as much in retirement savings!

Disability Insurance And The Risks To Human Capital

One of the key risks to consider in these alternative types of retirement is that when retirement savings never accumulates as high (or at least, not until much later), and are more reliant on earned income and “human capital”, the individual doesn’t have as much of a buffer against truly unexpected retirement – e.g., due to disability. Social Security provides at least some safety net, but may be far below the standard of living he/she is accustomed to.

Arguably, this makes disability insurance even more important than it already is, in the future of retirement. An important consideration, given that in practice today, disability insurance still isn’t actually utilized very much (with only a 33% participation rate for group long-term disability insurance in today’s work environment, and relatively little private disability insurance adoption). And even then, it typically only goes until age 65 and provides a bridge to relying on Social Security in “traditional” retirement.

The good news, at least, is that as medical advances proceed, and we continue to “square the curve” on longevity, we may be less likely to be disabled in the first place. Nonetheless, though, this implies at a minimum that having an even larger emergency savings to help navigate the transitions becomes more important.

The bottom line, though, is simply to recognize that alternative types of retirement have the potential to substantially change traditional retirement advice. With planned semi-retirement or sequential temporary retirements, retirement savings will not be invested nearly as long term (which demands a different portfolio composition), and will never accumulate as high (since there isn’t nearly as long of a non-work period). In turn, emergency savings and disability insurance become even more important, as do other key human-capital-related elements of financial advice, from guidance on career advice to job retraining to help navigate each ‘re-entry’ after a transition phase, or to find an appropriate semi-retirement role.

As noted earlier, though, with the latest Age Wave study already showing that the majority of today’s pre-retirees don’t actually intend to engage in the “traditional” retirement approach, it’s time to consider whether retirement advice itself needs to shift from being less retirement-portfolio-centric. Which could actually be a substantial transition – and substantial challenge – to today’s financial advisors, as our business models are increasingly focused on an assets-under-management approach that has a natural bias towards just one of the three types of retirement (and our financial planning software is not well built to model alternative types of retirement strategies). Which in turn raises the question of whether as financial advisors, we ourselves are fully prepared – from our advice and value proposition, to our business models and software tools – for the alternative types of retirement that the future may hold!?

So what do you think? Will most people find traditional retirement fulfilling? Do you see more clients engaging in alternative forms of retirement? Do we need new strategies to address saving and risk management for different types of retirement? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

If you think the final bill will have noticeable tax increases for an entire bracket section of the population you’re dreaming. No way it would get out of 2 GOP Ways and Means committees.

It would be profoundly foolish to try to accelerate income into 2016.

It’ll either be the same or fall on the income bracket side. If someones individual(not capital gains) tax rates do rise it’d likely be the result of a less visual change such as removal of head of household brackets or removal of child exemptions (the latter of which I also find unlikely to make it out of committee), not an entire segment of income that is now at a higher marginal rate.

The donor advised fund suggestion is a good 1 on 2 levels. Possibility of deduction cap and also the most likely benefit in getting a deduction at a higher tax bracket today than there will be in the future.

On the capital gains side I could possibly see a rise in either the 0% bracket or possibly some smooth over rate that is a little higher, but I still wouldn’t count on that.

Bear in mind there’s a BIG difference between marginal tax rates, and effective tax rates.

The House GOP will try to equalize the EFFECTIVE tax rates, as that’s what ensures that the total tax burden does not rise for particular segments of households.

That doesn’t mean, though, that a significant slice of MARGINAL income couldn’t face a higher marginal tax rate next year.

In the logical extreme, I could take a $100,000 taxpayer and give them a 90% tax rate and a $90,000 standard deduction; their marginal tax rate is higher (at 90%), but the effective tax rate is a mere 9%… still, that person would have still been even BETTER off by accelerating $10,000 into this year at 25% (instead of 90%), and then letting the remainder of their income be taxed next year (at 0%, offset by the standard deduction).

There are many, many similar permutations where marginal tax rates are higher for a slice of income, even if total tax burden is similar or lower.

– Michael

If there was a chance they were setting things up that way, I would agree with everything you said and the ensuing analysis, but there really isn’t a chance things will play out like that.

1) The GOP claims they want to cut deductions into their lower brackets, not increase them into higher brackets.

2) GOP wants the PR value of lower brackets pretty much across the board because the population doesn’t think in terms of effective rates. They see the published marginal rates.

3) Practically speaking 5% (33-28%) marginal rate on $200K of taxable income isn’t going to be made up by any exemption or standard deduction amount that

Certainly a worthwhile point, but realize that a big piece of GOP’s desire to “simplify the tax code” is so they can get the PR value from their base on how low tax rates are. The population doesn’t think about effective tax rates, instead they tend fixate on %’s associated with the brackets.

So while the GOP may not care about a slight increase in the 10% bracket as long as its offset by an exemption/standard deduction, they’re not going to let a large swath of the 28% marginal rate get consumed by a new 33% marginal rate. Won’t happen, nor could a larger standard deduction touch that 5% of ~$200K.

Disregard the repetition in the last 2 paragraphs

“Practically speaking 5% (33-28%) marginal rate on $200K of taxable income isn’t going to be made up by any exemption or standard deduction amount that”

Anonymous, the step up from 28% to 33% only applies to income of $6,450K (income between $225,000 and $231,450). That equates to about $322 in additional income tax.

It’s a trivial amount and could easily be made up by a larger standard deduction amount from that which exists today.

Separately, what the GOP wants and what is passable in terms of tax reform might not be the same thing (i.e,, compromises will likely need to be made). I’d be hesitant speaking with such certainty (isn’t a chance… or not going to happen…) when dealing with any potential future legislation in our country.

Mike,

I think Anonymous was talking about the step-up for individuals, not married couples, which is a much wider range.

Although the irony is that if the GOP wants to “fix” the marriage penalty, this is the way it “has to” be done. Unless they align it so the 33% bracket for INDIVIDUALS lines up with 33% under the old system, but that would dramatically expand the 25% bracket for married couples, resulting in a gargantuan tax cut for upper-middle income couples that probably won’t score well from a budget perspective…

– Michael

Well that is true (much bigger disparity for inviduals). Have not filed as individual in 30 years so my eyes tend to gravitate toward the chart that applies to me 🙂

Coverage I’ve seen on deduction changes doesn’t discuss proposed changes to income adjustments (see https://apps.irs.gov/app/vita/content/globalmedia/teacher/form_1040_adjustments_4012.pdf for current list). Any available info on possible changes there, and/or whether prepayment of some of these (i.e. alimony, student loan interest) is advisable before January 1?

Not knowing exactly what the future plan might be, it is hard to be absolutely pricise about the impact of changes. Having said that, you have done as good as job as could possibly be done of distilling this down into a concise and understandable summary. Nicely done!

Thanks Mike!

I gave my crystal ball of taxes extra an shake today! 🙂

– Michael

Michael,

Great article. I believe we will see more people engaging in alternative forms of “retirement”. My wife and I are setting ourselves up for exactly this situation. I am 39 and my wife is 33. I can retire from my current career in a few years at the age of 43 with an immediate $46K net (today’s dollars) inflation adjusted pension. We live below our means and have some retirement savings in 401K, IRAs and a rental property. If my wife and I didn’t work another day after that we could still live a reasonably comfortable life. My wife is finishing her Masters Family Nurse Practitioner Degree and plans to work full-time for at least a couple of decades. However, her profession is also great for someone who wishes to scale back and work part-time in the future and it’s possible to find suitable and diverse employment in all but extreme cases of disability. I personally can’t imagine not working when I retire from this career and thus I’m currently completing my Master’s in Family Financial Planning from the University of Alabama with an interest in working in the field. For me “retirement is really more about doing different and perhaps more

fulfilling (but not necessarily zero-income) work”…as you put it. Increasingly, I am finding that many people are approaching retirement with this same mindset.

With need for health insurance (group-insurance, or ACA/Obamacare) prior to Medicare/Medicaid eligibility age., some income (and health-coverage — either thru employer or thru ACA) actually helps to achieve this goal !! Also – the most important hedge against future un-known costs — is maintaining/performing some current/relevant skill to get/stay employed (even though in limited capacity/hours).

If you look at cost of ‘high-end’ smart-phone with a fruit logo — they’ve increased substantially over the years. Obviously, you can be lot more productive, or have more fun with those smart-phones – but they do cost real and ever-increasingly-more monies !! How you buy or gift one of those without decent income (besides limited SS and/or limited pension/401K withdrawals)

Great points! Fortunately my Health Insurance for the entire family will only cost me $600 (today’s dollars) in premiums per year with an Individual Annual Deductible of $150 and $300 total for the Family, Catastrophic Cap 3K and very minimal cost for Labs, Inpatient, Outpatient, Ambulance etc. I agree about the importance of maintaining/performing a relevant skill to get/stay employed. There is no doubt things like smart-phones have become very expensive. They are so expensive that I chose to get rid of mine almost 3 years ago and I haven’t owned one since. I miss some of the functions a lot but don’t find the total value to be worth what is charged.

Curious: what career lets you retire so early with such a good pension?

Stevie it’s a military retirement. It has a 20 year cliff vesting period. Most people who start in the service don’t stay in long enough to get it…I think it’s something like 15%. I have also been very fortunate in that I reached the maximum pay grade in the enlisted force. In my case it will be E-9/24 years of service. If I served for 30 years/until I was 49 years old I would receive $60K per year (today’s dollars) payable immediately. It would be around $70K (future dollars) by the time I would retire with 30 years (2026). By that time my 24 year retirement will have grown to $50K and continue to adjust with inflation each year. Considering the $20K gap between 24 and 30 years it’s a really hard decision. It’s highly unlikely I will get out and earn the 150-160K per year (or more) I’d need to replace my income and produce an extremely low risk $20K inflation adjusted stream of completely passive annual income during that 6 year period. If I were ever going to make up the difference it would have to be on the back end. That being said, if I do decide to retire at 24 years I’ll be perfectly fine should I never make up the difference. Another benefit of this pension is that it’s not taxed by some states that generally tax pensions. I’ll definitely choose to live in a zero income tax state or a state that chooses not to tax the pension. I may also receive a service connected disability rating when I retire that could result in further payments and potentially no taxes on any of it (fortunately up to this point I’m healthy and plan to remain healthy so I’m hoping not to partake in those benefits.)

I figured it was a military or public safety (police, fire, etc) type pension. That 20 year cliff vesting is a bummer, but earning more credits does sound tempting. During my career, I encountered several ex-military that retired around the 20 year mark and transited right into the private sector.

Interesting theory, one I have seen before. However, what people say they will do vs. what they actually do is more instructive. The average age of retirement in the US is 62 and about one third of those who retire do so involuntarily. Our clients are skewed older and wealthier but even they have health problems and lose the ability to work constructively. Thirty years of experience tells me it is more likely than not that our clients will be forced to retire for reasons of health, theirs or a loved one’s, much earlier than projected by these alternative models.

Exactly. Stats I’ve seen indicate folks retire about 7 years earlier than anticipated, about half due to health or career issues. And where are all these full/part time jobs going to come from? With corporations eagerly tossing age 50+ workers and refuse to rehire? Part time or temporary work may be career dependent. In areas like tech, part time work is almost unheard of, stepping away even for a short while makes you unemployable. And the idea everyone can become consultants or self-employed strikes me as sketchy at best.

Interesting to square this with the reality that work, in general, is being made obsolete by automation, robots and artificial intelligence. One wonders what disability insurance policies will look like in that world.

Michael, I shared this article with several of my co-workers and it served as a catalyst for a very interesting discussion. The younger ones (under 35) were more interested in the mini retirement scenario, while others (35-50 range) wanted to learn more about the extended sabbatical scenario. Our conversations also led to a discussion of an alternate scenario: part-time jobs during sabbaticals from the career job. This would provide the opportunity to explore other interests while still generating income and enjoying more leisure time. This was definitely an interesting read – thank you!

Thanks for this, Michael! One of the questions that comes up for me is how to best go about saving then? Traditional retirement savings vehicles penalize for taking money out before 59.5, but provide a tax deduction (if you qualify) and tax deferred growth. Standard brokerage accounts don’t limit your access by age, but are taxable throughout. I am aware of the strategy to maximize and HSA, then pay health expenses out-of-pocket and save receipts to claim at any point in time. Any other ideas or strategies that you can think of to help balance timing and taxes? Thanks so much! -Kate

A few ideas:

Rental real estate generates recurring revenue (with some risks involved, as we’ve seen). I know a lot of people who are regularly using savings to buy real estate for this purpose. You can get some really interesting tax efficiency by holding your real estate in an S Corp.

Dividend-paying assets also deserve some consideration. It takes a lot of money to build a retirement income stream based on dividends, but they are tax-efficient (qualified dividends are taxed at capital gains rates) and can yield more than 4%, particularly in the closed-end fund space.

401(k) and 403(b) plans can be accessed after age 55 if separated from service, which gives folks with those accounts a head start on retirement if they want to access those funds penalty-free.

Roth IRAs are FIFO, so contributions can be tapped prior to 59.5 without penalty. Along these lines, if you knew you were planning for an early retirement and had at least 5 years to work with, you could convert a portion of an IRA to a Roth and after 5 years access the converted funds without penalty. You’d need to pay the taxes out of pocket tho.

Last thing I can think of without getting into insurance products: people can do capital gains harvesting to maximize the basis in their taxable accounts. You sell and immediately rebuy your stocks/funds on a regular interval. This spreads the capital gains hit out over many years and resets the taxpayer’s basis in the account. It’s like a Roth conversion for a taxable account in a way.

On the insurance front: IRAs can be accessed prior to age 59.5 via an annuity, the income stream from which qualifies for 72(T) treatment. Not necessarily ideal, or what most people are looking for, but it gets around the early distribution penalties. If you know how much income you need and when, you could roll an IRA into an annuity with an income rider to cover a portion of the income need. Not tax-efficient though, unless the IRA in question is a Roth.

Whole life insurance cash accumulations can be accessed tax-free via loans. VERY little literature on this other than what insurance companies and agents churn out. I don’t know of any studies showing evidence of life insurance loans in retirement being a long term viable income stream, but they are certainly positioned this way by the carriers. Loans are not taxable, the death benefit pays the loan off, overloan provisions prevent the policy owner from taking too much out, and you don’t have to take the loans out every year (unlike an annuity which will pay out the income stream regardless of whether or not you need it in a given year). It takes YEARS to build up a significant cash accumulation, though, so this is a non-starter for a lot of folks.

Hope this helps!

Michael Kites:

In the old days – say 1889 Prussia or in the USA or UK, etc., – many, many folks lived well beyond the age of 45.

The reason that the “average” life span in those days was 45 years of age was due almost entirely to the very high infant/child/early adolescent mortality rate due to diseases (mostly all eliminated today) which affected mostly infants and other young folks. (Average 75 years of age and 5 years of age and you obtain 40 years of age). Also, many just born children in the old days died within a few days of birth.

For those who made it past , say, 20 /25 years of age, on average they lived just about as long as we do today.

How do we know this? Data is likely sparse….

There is data on this, and John is correct:

https://priceonomics.com/why-life-expectancy-is-misleading/

Yaval Noah Harari talks about something similar in Sapiens: namely that fossil records indicate that life expectancy for ancient hunter gathers was similar to life expectancy today, if you correct for infant and child mortality between the ages of 0-5.

https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007%2F978-3-319-16999-6_2352-1

I think the point being missed here, and forgive me if I just overlooked it, but in the alternative retirement savings scenarios the person, or couple, is screwed if, for health reasons, he/she cannot work past a certain age. The other factor is whether you can move in and out of the job field and still have the same earning potential. The first you could insure against, at a high cost; the second cannot happen in a lot of career choices.

Had never equated and compared the $40,000 per year earned on $1,000,000 @ 4%, against what I would have coming in monthly from pensions, Social Security, and savings, etc. At that rate I would have $1.25 million banked for retirement (before taxes)! Woo-hoo! Who’s your Daddy?