Executive Summary

After five years of policy shifts, paused payments, and temporary relief measures, the Federal student loan system is entering a new phase – one that's more stable, but also less generous and far more limited in its options. Before COVID, the system was complex but relatively stable. Then came years of borrower-friendly interventions, from suspended loan payments and interest freezes to sweeping (if temporary) forgiveness initiatives. Now, with the passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), a new framework is taking shape – significantly narrowing borrowing options and increasing repayment obligations, particularly for parents and graduate students.

For financial advisors, the OBBBA represents a meaningful structural shift – especially in how much students and parents can borrow. While the past several years focused on temporary relief and evolving repayment plans for existing borrowers, the new borrowing limits will directly affect college funding strategies going forward.

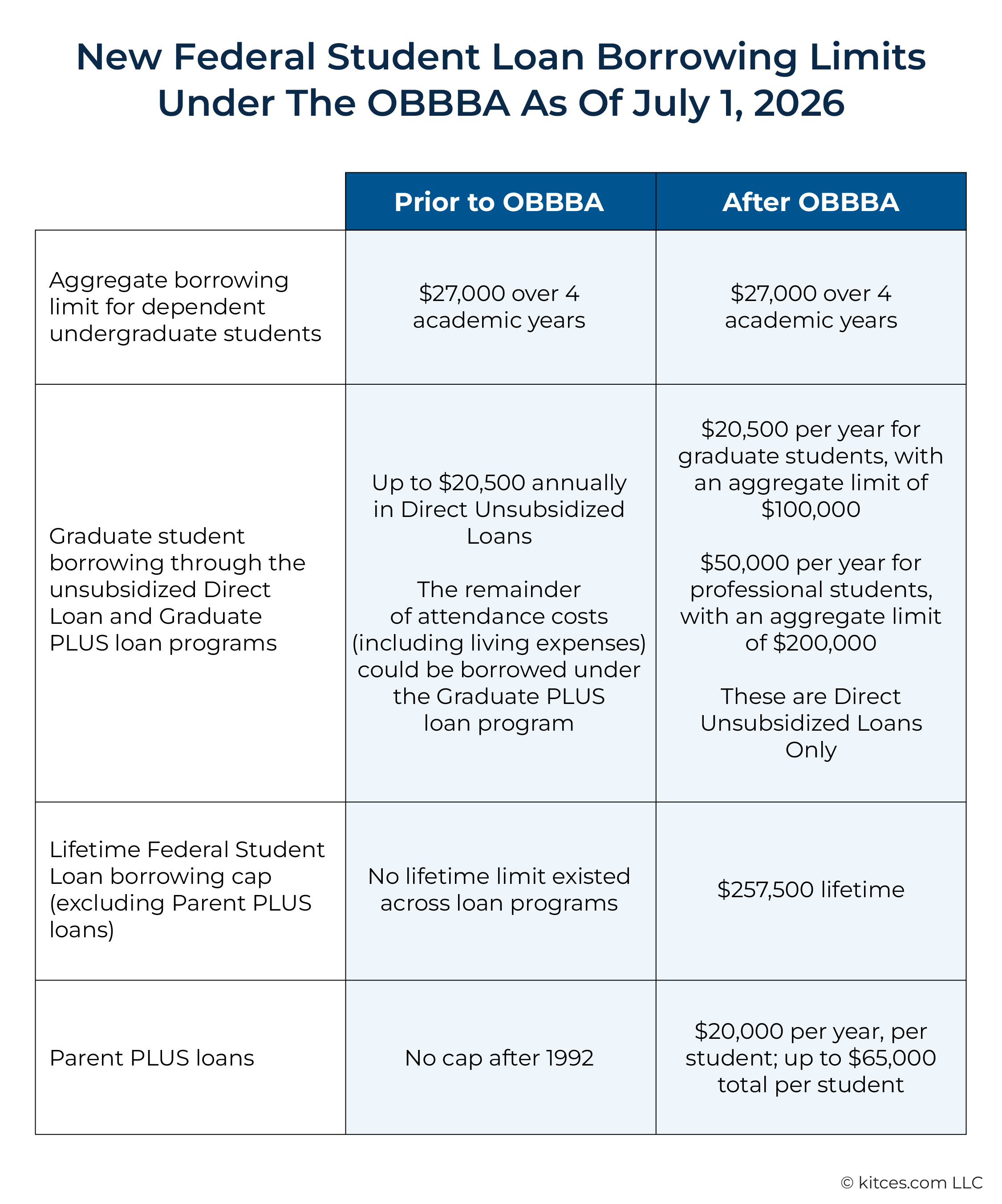

Specifically, undergraduate borrowing limits remain unchanged, with a Federal loan cap of $27,000 over four years (or $31,000 for students taking longer to complete their degree). But for the first time in decades, OBBBA sets firm caps on other loan types: Parent PLUS loans will now be capped at $20,000 per child, with a $65,000 lifetime cap per student. Graduate PLUS loans will be eliminated entirely, leaving the Direct Unsubsidized Loan program as the sole source of Federal borrowing for graduate students – with pre-existing annual caps of $20,500 ($50,000 for professional degrees) and aggregate limits of $100,000 ($200,000 for professional students). The legislation also introduces a new combined lifetime borrowing cap of $257,600 across all Federal loan programs (excluding Parent PLUS loans).

In addition to new borrowing limits, the OBBBA brings major changes to student loan repayment plans. These include a balance-based Standard Repayment plan that will tie repayment terms to loan size, and a new Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plan – the Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP) – that will become the default for many borrowers. RAP calculates monthly payments based on a progressive formula tied to Adjusted Gross Income, fully subsidizes unpaid interest (eliminating negative amortization), and offers forgiveness after 30 years of repayment. All legacy IDR plans will be phased out by July 2028.

Notably, the next few years will present an opportunity for financial advisors to provide critical student loan advice to clients transitioning between repayment plans – particularly for those whose monthly payments will change significantly under different plan options or for those who are pursuing Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF). Advisors may also need to revisit college savings strategies with families as Parent PLUS loans become more restricted, which could mean exploring private lending or other alternatives where appropriate.

Ultimately, the key point is that while student loans may be entering a period of more stability, that stability comes with new complexity. Advisors who stay current on the evolving repayment rules, deadlines, legislative changes, and planning implications will be well-positioned to offer tremendous value – both to borrowers navigating repayment and to families rethinking how they'll pay for college!

Over the last several years, the student loan landscape has undergone a massive transformation – policy shifts, legal battles, and economic disruptions have left many borrowers uncertain about the future. For financial advisors, this changing environment presents both challenges and opportunities – helping clients understand where things stand now, and how to navigate what's next.

After five years of upheaval regarding all aspects of student loan repayment, the system seems to be stabilizing. Before COVID, the student loan system could be described as complex but stable. Since the Trump administration froze loan repayment and interest in March 2020, the system could be described as unstable but borrower-friendly, thanks to broad forbearance, paused interest, and sweeping forgiveness initiatives. And, in the wake of the passage of the "One Big Beautiful Bill Act" (OBBBA), the student loan system appears to be entering a new phase: one that has fewer options and is more stable, but also far less generous to borrowers.

Historic Backdrop – Complexity, Relief, And Confusion

To better understand how the current rules came to be – and why many clients may be confused or faced with urgent decisions – it's worth revisiting the recent history of the student loan system. From the proliferation of repayment plans prior to the pandemic to the sweeping but temporary relief measures that followed, this backdrop reveals the deeper patterns that continue to shape planning conversations today.

Pre-COVID: Stability Without Confidence

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the student loan system had grown increasingly complex – and increasingly difficult for borrowers to navigate. At the start of 2020, 43.1 million Americans held a total of $1.54 trillion in outstanding student loan debt – most of it owed to the Federal government. That figure had grown by 90% over the prior decade, reflecting both the increasing costs of post-secondary education and the lack of progress in repayment for many borrowers.

By that point, the Department of Education had introduced a wide variety of repayment plans, including several options for time-based repayment plans (standard, extended, graduated, and graduated extended) and a growing list of Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plans. IDR plans calculate monthly payments based on income and family size, and offer loan forgiveness after 20 or 25 years of qualifying payments, depending on the plan. The first IDR plan, Income-Contingent Repayment (ICR), launched in 1994 as part of the Student Loan Reform Act of 1993. This was followed by Income-Based Repayment (IBR) in 2009, Pay As You Earn (PAYE) in 2012, a revised version of IBR (New IBR) in 2014, and Revised Pay As You Earn (REPAYE) in 2015.

Each successive plan included slightly more generous provisions, such as caps on monthly payments, limits on interest capitalization, and the option for married couples to exclude spousal income by filing taxes separately. Despite their potential to reduce monthly payments, adoption was uneven. By 2017, only 27% of Federal student loan borrowers were enrolled in an IDR plan, though those borrowers held 45% of total loan balances. And many of those enrolled in these plans were stuck in a pattern of negative amortization, making low monthly payments that didn't cover the monthly interest accrual, leading to growing loan balances over time.

Prior to 2020, forgiveness under IDR and Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) was also rare. This was largely attributed to how new these programs still were. But it also stemmed from confusing and inflexible program rules, low initial enrollment, and, in some cases, misleading information provided by loan servicers – all of which undermined borrowers' ability to qualify.

COVID-Era Changes: Opportunity And Confusion

In March 2020, the Federal government announced emergency relief for student loan borrowers. The Trump administration initially paused interest accrual and suspended required payments for Federal student loans for at least 60 days. This freeze was extended to September 30, 2020, with the passage of the CARES Act, which also clarified that suspended payments would count toward PSLF and IDR forgiveness. Ultimately, the freeze would be extended eight times – twice under President Trump and six more times under President Biden – before finally expiring in October 2023.

During these three years, the Biden administration implemented several reforms aimed at restoring borrower confidence in the PSLF and IDR programs. In October 2021, the Department of Education announced the PSLF limited waiver, allowing borrowers to receive credit toward PSLF for prior repayment periods while working for a qualified employer, regardless of repayment plan or loan type, and for certain periods of deferment or forbearance to count as well. The waiver benefited more than one million borrowers, with $74 billion in debt forgiven as of October 2024.

Building on this momentum, the Department of Education launched a similar initiative for IDR borrowers in April 2022. This adjustment gave credit for certain prior repayment periods and applied to borrowers who had consolidated Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) balances into Direct Loans. At the time, the Department of Education estimated that the initiative would lead to immediate forgiveness for thousands of borrowers and significantly accelerate progress toward forgiveness for 3.6 million more.

Later in 2022, the Biden administration attempted to implement a one-time debt cancellation program, offering up to $20,000 in relief to borrowers earning under $125,000 as individuals ($250,000 for joint filers). The plan would have canceled entire balances for an estimated 20 million borrowers and reduced debt for 43 million overall. But in the following summer of 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the policy exceeded executive authority under the HEROES Act, blocking implementation.

Soon after that ruling, the Department of Education launched a new repayment plan – technically a revision of REPAYE – known as the Saving on a Valuable Education (SAVE) plan. SAVE featured $0 monthly payments for single borrowers earning less than $35,000, full interest subsidies to prevent negative amortization, and shorter forgiveness timelines for borrowers with small balances.

Nearly 8 million borrowers enrolled in SAVE, but in July 2024, the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals issued an injunction that blocked full implementation of the plan. Borrowers were placed in administrative forbearance with no interest accrual. However, any payments made during this period have not counted toward PSLF or IDR forgiveness. In the months that followed, borrowers who attempted to switch out of SAVE faced long processing delays, meaning they were not making progress toward forgiveness and also could not do much of anything about that reality.

For financial advisors, the policy back-and-forth of this period left many clients unsure how to proceed, with significant implications for those relying on forgiveness strategies or locked into the SAVE plan, with critical details paused or under review by the courts.

Student Loan Changes In The OBBBA Law

For financial advisors, the changes introduced under OBBBA represent a meaningful shift in the structure of the Federal student loan system – especially when it comes to how much students and parents can borrow. While much of the past few years focused on temporary relief and evolving repayment plans for existing borrowers, these new limits bring changes that will directly affect college funding strategies going forward.

New And Changed Limits On Borrowing

While the availability of repayment plans has evolved steadily over the past few decades, the underlying structure of the Federal student loan system has remained largely unchanged since the transition to Federal Direct Loans in 2006. However, under the OBBBA, major changes are coming for new student loan borrowers that will reshape the availability of Federal student loans under the Parent PLUS, Graduate PLUS, and Graduate Unsubsidized Direct Loan programs.

For dependent undergraduate students taking on their own debt, borrowing limits remain unchanged. The aggregate Federal loan cap continues to be $27,000 over four academic years (up to $31,000 when taken over more than four years), split between subsidized and unsubsidized Direct Loans. However, for graduate and parent borrowers, the law sets firm borrowing caps for the first time in decades.

When Parent PLUS loans were first created in 1980, they carried an annual cap of $3,000 per year. That cap was eliminated in 1992, and as of the second quarter of 2025, more than 3.6 million families collectively held $114.3 billion in outstanding Parent PLUS loans. Under the new law, annual borrowing will be capped at $20,000 per child, with a total lifetime cap of $65,000 per student. Parents borrowing for a student already enrolled in an undergraduate program may continue borrowing at their prior levels for up to three more academic years.

The Graduate PLUS loan program, established under the Higher Education Reconciliation Act of 2006, allowed students in graduate and professional degree programs to borrow up to the full cost of attendance not already covered by unsubsidized Direct Loans – including tuition, fees, and living expenses. As of the second quarter of 2025, 1.8 million borrowers had $117.2 billion outstanding in these loans. However, the OBBBA eliminates the Graduate PLUS program entirely, leaving the Direct Unsubsidized Loan program as the sole source of Federal borrowing for graduate students, with a pre-existing annual cap of $20,500. This cap is increased to $50,000 per year for students in professional degree programs. An aggregate loan limit is $100,000 for graduate students and $200,000 for professional students. Additionally, the law establishes a combined lifetime borrowing cap of $257,500 across all Federal student loan programs (excluding Parent PLUS loans), where no such cumulative cap previously existed.

Similar to the Parent PLUS changes, the law includes an interim exception for graduate students who, as of July 1, 2026, were already enrolled in a qualified program of study and had already received a Federal loan for that program. These students may continue borrowing under the prior limits for the lesser of three academic years or the remaining length of their current program.

Changes To Standard Repayment Plans

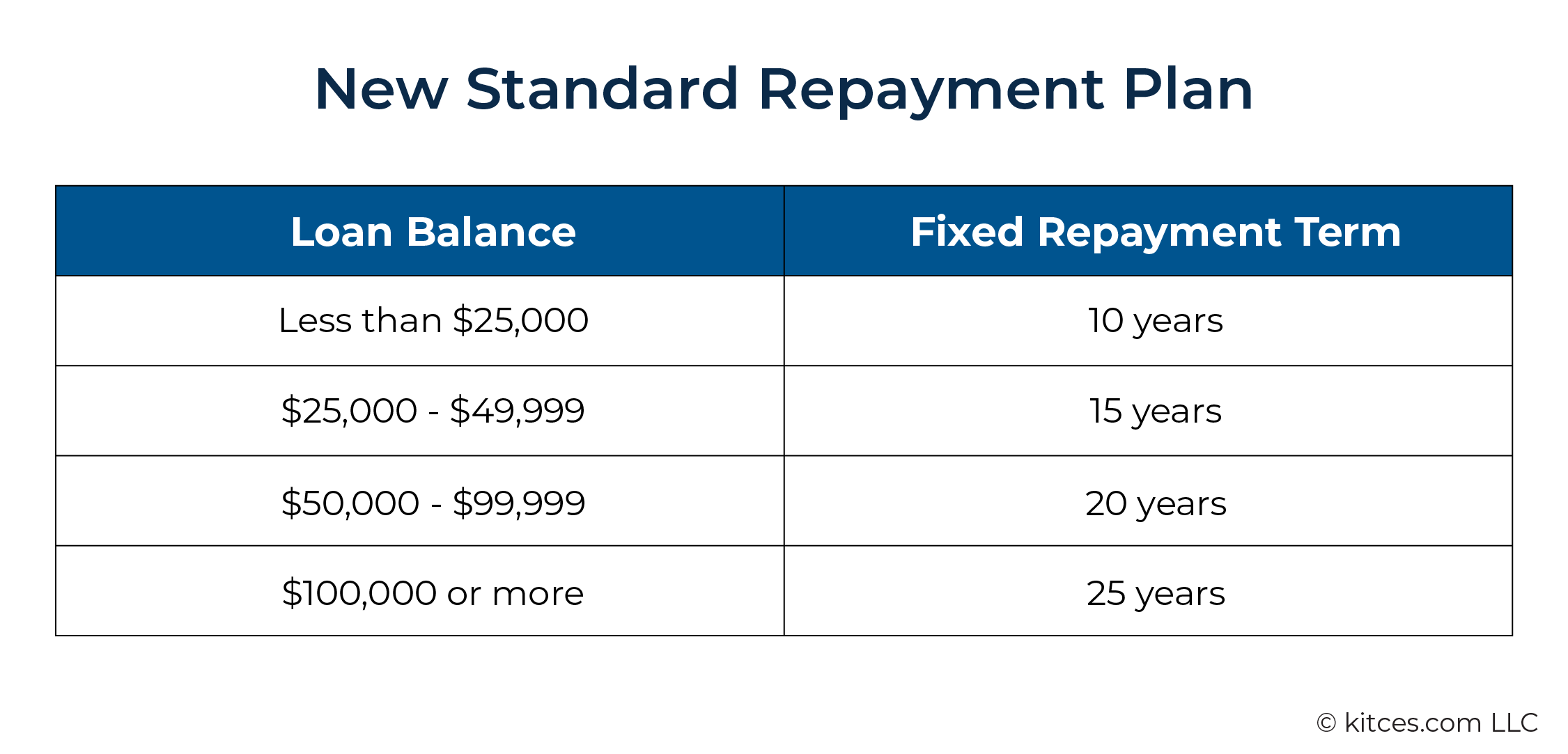

Prior to the OBBBA, borrowers would get a six-month grace period after finishing school and would then be placed onto the standard repayment plan. This was the default for any borrower who did not take action. The standard plan worked just like any other installment loan, with a level 10-year repayment period that would result in a $0 balance at the end of the 10 years.

Now, for all borrowers entering repayment on or after July 1, 2026, the default will shift to a balance-based standard repayment plan, with repayment terms that range from 10 to 25 years, depending on how much is owed. The term of the loan is determined by the balance; borrowers with smaller balances will remain on a 10-year schedule, while those with larger balances will be placed on progressively longer repayment terms.

While this change may reduce monthly payments for borrowers with higher balances, it introduces an important need for action: By statute, only 10-year standard repayment plans are eligible for Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF). Borrowers automatically placed on plans with longer repayment terms will not earn PSLF credit unless they proactively switch to an eligible IDR plan.

OBBBA also eliminates the option to enroll in the extended and graduated repayment plans for any borrower entering repayment after July 1, 2026. These plans had been used less frequently and were typically only optimal in very specific circumstances.

The Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP)

With the proliferation of Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plans over the past 25 years, student loan borrowers were faced with many similar options, each with slight differences that could be advantageous to specific borrowers. The OBBBA dramatically reduces the options for student loan repayment tied to income – by July 1, 2028, the ICR, PAYE, and SAVE (formerly REPAYE) plans will be eliminated for all borrowers.

Going forward, borrowers will have only two income-driven repayment options:

- Income-Based Repayment (both the Old and New IDR plans)

- Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP)

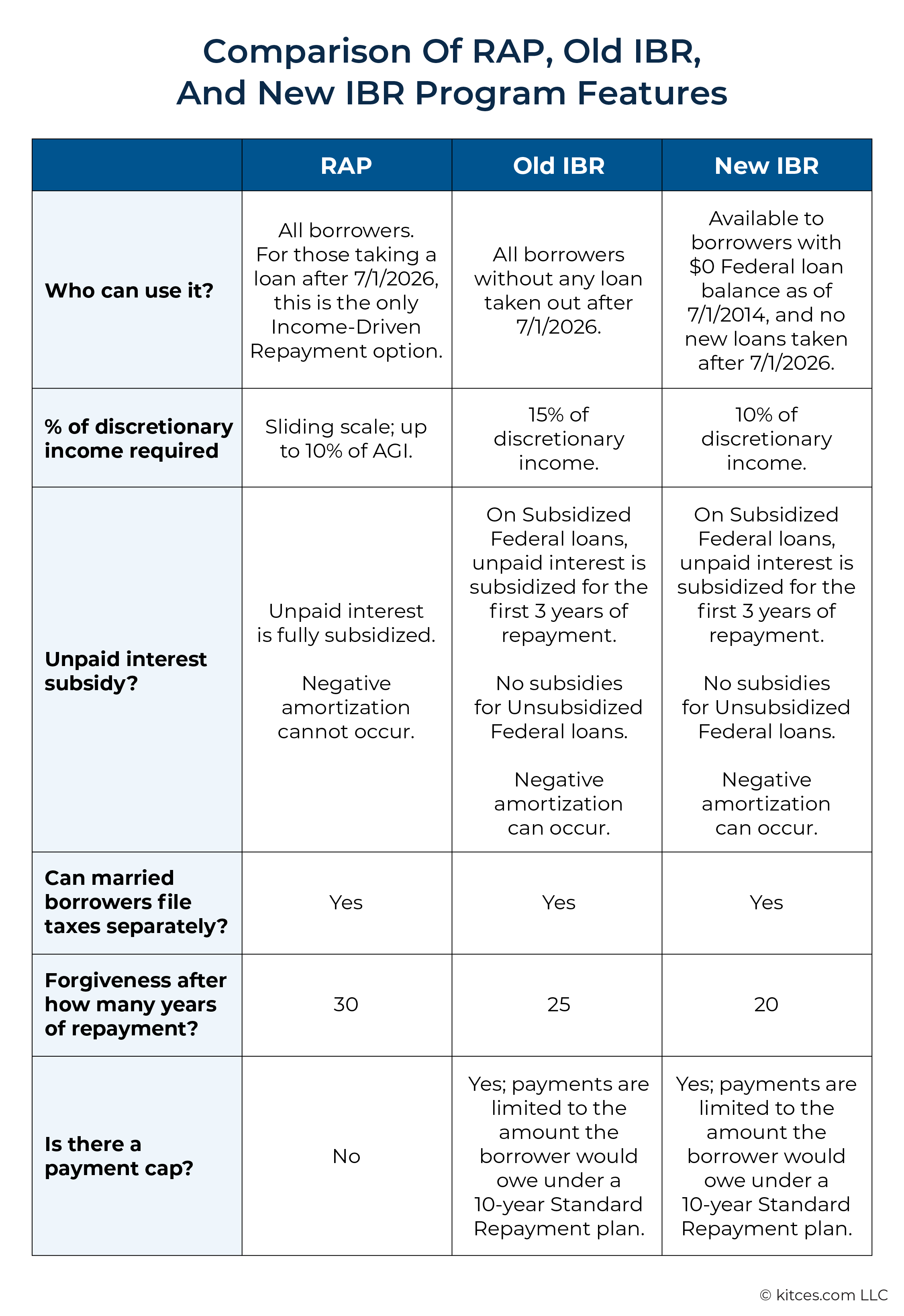

Both versions of Income-Based Repayment (IBR) remain available for all borrowers with loans taken out prior to July 1, 2026. But for anyone who takes out any Federal student loans after that date (including currently enrolled student borrowers), their only option for an income-driven plan will be RAP.

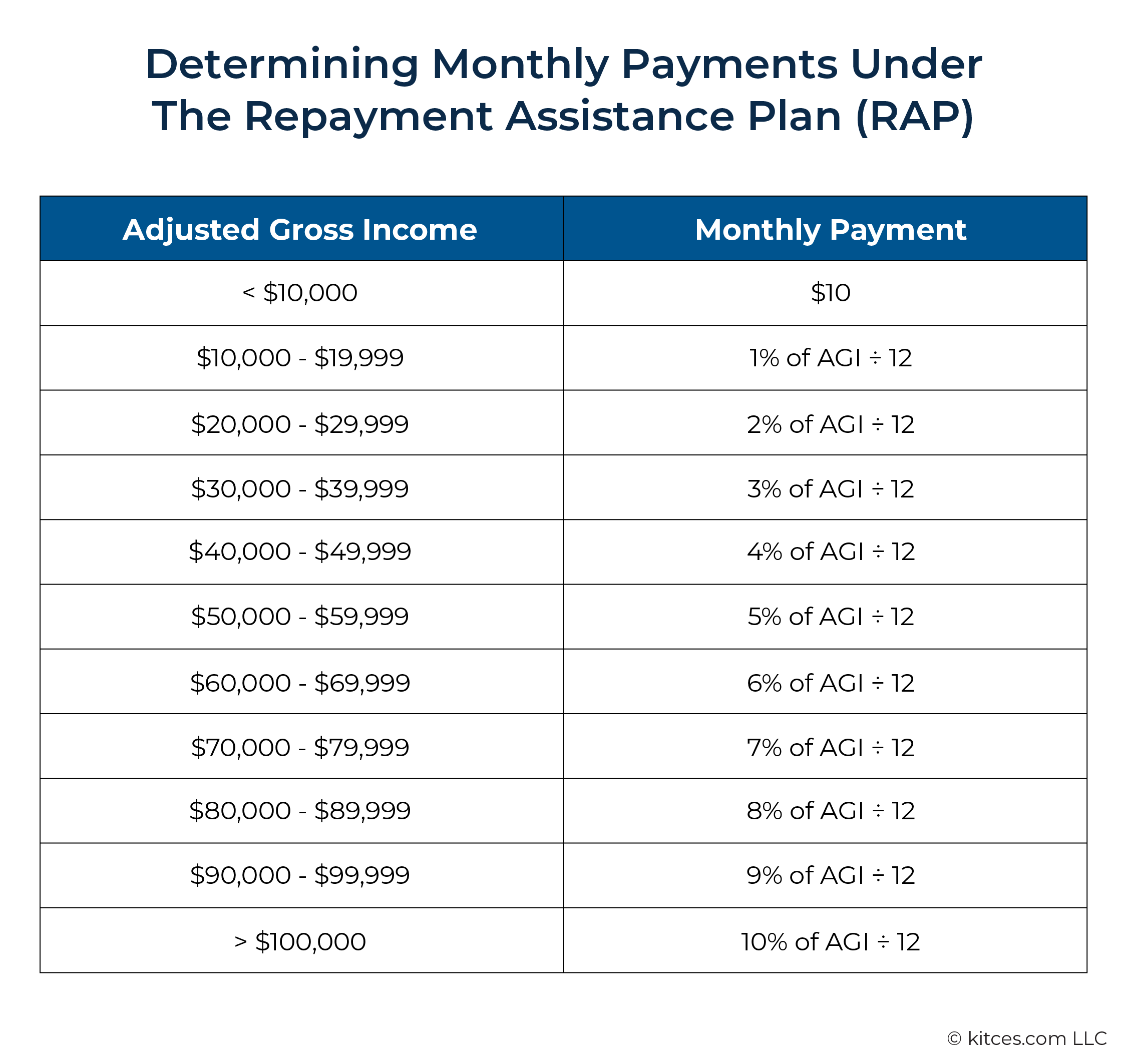

The Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP) calculates monthly payments based on a progressive formula tied to Adjusted Gross Income (AGI). As income rises, the monthly payment is calculated as an increasing percentage of AGI, with a flat $10 minimum for very low-income borrowers.

The table below outlines how monthly payments are determined under RAP, based on AGI. Additionally, a very simple online calculator to determine RAP student loan payments can be found here.

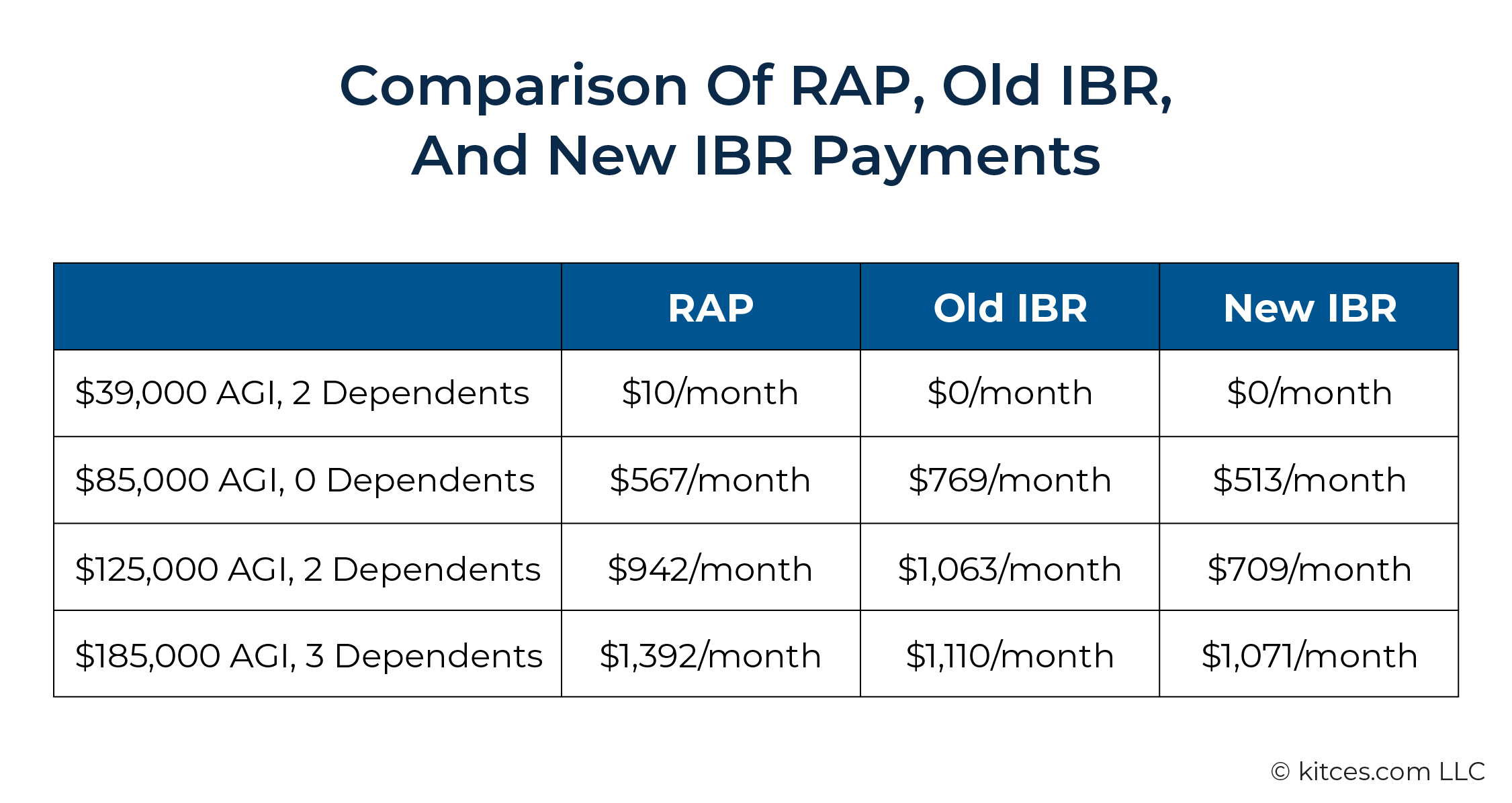

In addition to the AGI-based formula, borrowers receive a $50/month reduction in their required payment for each dependent claimed on their tax return. Although required repayment amounts under RAP will generally be higher than they would have been under the now-paused SAVE plan, they will often be lower than payments required under IBR – especially for borrowers with dependents or modest incomes.

The table below summarizes how RAP compares to Old IBR and New IBR across several key features, including how interest is treated, whether married filing separately is allowed, and how long borrowers must remain in repayment before forgiveness.

A major provision of RAP is its treatment of interest. Unlike under prior IDR plans – which often resulted in negative amortization when monthly payments don't cover interest – RAP fully subsidizes any unpaid interest after each month's payment, which means that unpaid interest is not added to the loan balance at any point. Additionally, RAP guarantees that loan balances will drop by a minimum of $50 each month, even if the borrower's required payment does not fully cover the monthly interest amount.

Example: A borrower has a required $400 monthly payment, and their monthly interest accrual is $700/month.

The $300 interest gap will be fully subsidized and the loan balance will still drop by $50 per month.

Borrowers on RAP for 30 years will be eligible for loan forgiveness – though the forgiven balance will be considered taxable income under current law. This forgiveness period is longer than the 20- to 25-year periods under prior IDR plans.

RAP also preserves the option to file taxes as married filing separately, allowing married borrowers to exclude spousal income when calculating student loan payments.

The chart below illustrates how RAP payments compare to Old and New IBR in several common income and household scenarios.

IBR No Longer Requires Partial Financial Hardship

The IBR plan has historically required borrowers to demonstrate a Partial Financial Hardship (PFH) in order to enroll. A PFH was defined as a situation in which a borrower's loan payments on a standard 10-year repayment plan exceeded 15% of the difference between the borrower's AGI and 150% of the poverty line. In practical terms, this meant the plan was not useful for those with a high income relative to loan debt, so IBR was not an option to use while in pursuit of PSLF.

The OBBBA removes this requirement, making IBR available to any borrower, regardless of income level or debt-to-income ratio.

This change is especially meaningful for high-income borrowers pursuing PSLF. With the planned elimination of PAYE and ICR, many borrowers with higher incomes but older loans would have had no PSLF-eligible repayment option before RAP becomes available – effectively creating a two-year gap in PSLF eligibility due to the SAVE forbearance. However, by removing the PFH requirement, these borrowers may access IBR immediately and continue earning PSLF credits in the coming 12 months that they otherwise would have had no route to get credit for.

From a planning perspective, it's important for advisors to run the numbers for clients, as RAP generally results in lower payments than Old IBR – except for those with higher incomes who benefit from IBR's payment cap, which limits payments to the 10-year standard amount. For those borrowers, Old IBR remains more favorable than RAP. On the other hand, RAP nearly always results in higher payments than New IBR (unless a borrower can benefit from a capped payment), and generally leads to higher payments than borrowers on the old PAYE, REPAYE, and SAVE plans (all of which have been – or will be – eliminated by July 1, 2026).

Public Service Loan Forgiveness: Unchanged For Now, But Changes Loom

While several proposals to limit access to the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program have been floated by GOP leaders under the second Trump administration, only one provision was introduced in the original House and Senate versions of the OBBBA. That provision would have excluded loan payments made during medical or dental internships and residencies from counting toward PSLF, a key part of the loan forgiveness strategy for borrowers in those professions. However, the provision was ultimately removed during the Senate's reconciliation process, which limits what can be included in budget-related legislation.

Since then, the Trump administration has continued to pursue changes to PSLF through the regulatory process. In March 2025, the President signed an executive order directing the Department of Education to revise PSLF eligibility criteria. The proposed rules would exclude borrowers working at certain nonprofit organizations from qualifying for forgiveness – specifically, organizations that support immigrants or transgender youth, advocate for civil rights or Middle East peace efforts, or are otherwise identified by the administration as inconsistent with its policy priorities.

In response, the Department of Education announced a negotiated rule-making process to carry out the executive order. Early proposed language would allow the Secretary of Education to unilaterally designate certain organizations as having a "substantial illegal purpose" – a designation that could disqualify them from PSLF eligibility. While the full impact of these proposals remains uncertain, the politicization of PSLF has further undermined borrower confidence in a program that already suffers from trust issues, despite having discharged $74 billion in loans for over a million borrowers as of October 2024. Any changes made here would likely result in lawsuits, as borrowers have signed promissory notes that reference the existing rules of PSLF, which include no clauses redefining public service beyond working at any 501(c)(3) nonprofit.

For now, though, the fundamental structure of PSLF remains unchanged. Borrowers must make 120 qualifying payments while working for a public or 501(c)3 employer to receive complete, tax-free loan forgiveness. The new RAP plan counts as a qualifying repayment plan under the current rules, but with recent staffing cuts at the Department of Education, processing delays have become more common – particularly for borrowers submitting PSLF employment certification forms or waiting for final loan discharge.

Parent PLUS Borrowers: Severely Impacted

Parent PLUS borrowers – typically parents of undergraduate students – have always been subject to more restrictive repayment options than other Federal loan borrowers. Historically, they have been excluded from the most generous income-driven repayment plans, with Income-Contingent Repayment (ICR) serving as their only IDR option.

Over time, many borrowers circumvented these restrictions through a double-consolidation process. By consolidating their loans twice in a specific sequence, they could reclassify their loans to become eligible for plans like IBR, PAYE, or REPAYE.

The Biden administration closed this loophole, but a final opportunity still remains. Parent PLUS borrowers who are not yet in an income-driven plan may still consolidate once into a Direct Consolidation Loan and enroll in ICR. These borrowers are expected to be transitioned to IBR sometime in the coming year. However, this opportunity ends on July 1, 2026. After that date:

- No new enrollments into income-driven plans will be allowed for Parent PLUS borrowers.

- Any new Parent PLUS loans (which are now subject to annual and lifetime borrowing limits) will only be eligible for standard repayment.

As a result, these borrowers will lose access to both IDR-based forgiveness and PSLF, making this a critical planning deadline for any families still relying on Parent PLUS loans.

Timeline of Key Changes

The implementation timeline for the OBBBA's changes spans multiple years, and as with past Department of Education efforts, some dates could shift due to operational delays. Additionally, the Trump Administration has previously expressed interest in eliminating the Department of Education altogether, which raises some uncertainty around the long-term oversight and administration of Federal student loan programs. If such a policy were pursued, student loan responsibilities could potentially be transferred to another agency, such as the Treasury Department.

Still, several major transitions are already underway or scheduled. For advisors, the following dates are especially important for planning around client eligibility and timing.

- August 1, 2025: Interest accrual restarted for those covered by the SAVE forbearance. (This is the result of executive action and was not a provision in OBBBA.)

- July 1, 2026:

- RAP Plan opens for enrollment. Any borrower with loans taken after this date will not be eligible for IBR.

- Deadline to consolidate Parent PLUS Loans for ICR/IBR Eligibility

- Borrowers on legacy IDR plans (ICR, PAYE, REPAYE/SAVE) begin being forcibly transitioned to IBR or RAP.

- July 1, 2028: Full phaseout of legacy IDR plans.

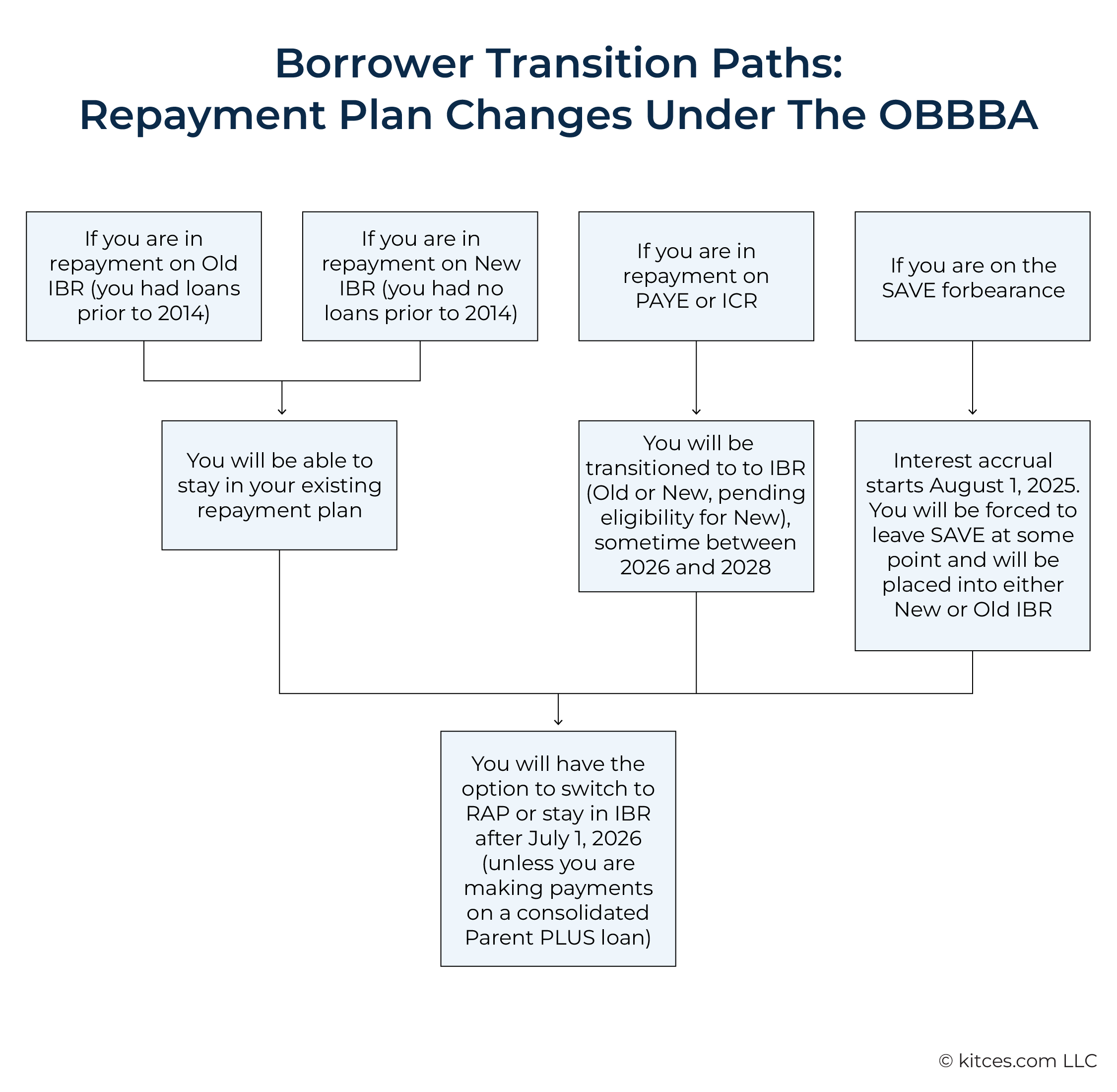

The implementation of these changes will affect borrowers differently depending on which repayment plan they're currently using and when their loans were originally taken out. The flowchart below summarizes how borrowers on various plans will be impacted, and when transitions to new repayment options are expected to occur.

How Advisors Can Think About The New Student Loan Landscape

After several years of shifting policies, legal uncertainty, and paused repayment obligations, advisors finally have enough clarity to give clear long-term student loan advice again. While the OBBBA substantially reduces student loan complexity for existing borrowers, the next few years will present an opportunity to provide critical student loan advice to many clients who are navigating transitions between repayment plans.

The first question for student loan planning remains the same: Should the client aim to repay their loans in full, or pursue loan forgiveness through either PSLF or on an IDR plan? But under the new framework, how that question gets answered may be different – especially for borrowers who will be limited to RAP as their route to PSLF.

For example, borrowers previously pursuing PSLF through PAYE, REPAYE, or New IBR may now face higher monthly payments under RAP, which could reduce the net value of pursuing forgiveness. Similarly, borrowers who were on track for long-term forgiveness after 20 or 25 years of IDR payments will now face a 30-year repayment timeline under RAP, potentially shifting the calculus toward full repayment.

It's also important to note that IDR-based forgiveness via income-driven repayment plans (but not PSLF) will once again be considered taxable income beginning January 1, 2026. Exclusion of forgiven loan amounts from taxable income had been granted under the American Rescue Plan in 2021, but the clause is scheduled to expire on December 31, 2025. Advisors modeling forgiveness-based repayment strategies should ensure any potential tax liability is factored into long-term projections.

How Financial Advisors Can Support Clients Through Student Loan Repayment Transitions

Borrowers who enrolled in the SAVE plan were often trying to minimize their monthly loan payments – many with the intention of pursuing forgiveness, either via PSLF or after 25 years of repayment. For nearly all of these borrowers, now is the time to consider switching to an Income-Based Repayment (IBR) plan. While IBR will result in a significantly higher monthly payment than SAVE would have, it will once again allow borrowers to earn credit toward loan forgiveness.

Some borrowers may remain on IBR until they qualify for forgiveness. Others might benefit from switching to RAP once it becomes available. Because RAP typically requires a lower monthly payment than IBR, it may be a better option for those pursuing PSLF. However, it extends the forgiveness window from 25 to 30 years, which may make it less attractive for borrowers pursuing long-term forgiveness, due to the increased total cost of repayment.

Nerd Note:

Both authors of this piece have experienced cases of student loan servicers incorrectly processing borrower requests to leave the SAVE plan. In July, each of us advised a client to switch to IBR. In both cases, the servicers (Mohela for one client, Nelnet for the other) initially confirmed the request – then later placed our clients back on SAVE. The reasons for these reversals are unclear, and it's not yet known how widespread the issue may be.

For advisors, this highlights the reality that these kinds of inconsistencies can happen regularly and stresses the importance of following up proactively with clients after plan change requests are submitted, reviewing servicer correspondence closely, and encouraging clients to document all communications in writing.

With these changes in mind, it becomes especially important to match each client's repayment approach to their long-term goals – whether they're pursuing PSLF, managing Parent PLUS loans, or preparing for future education expenses.

Strategies For Clients Pursuing Forgiveness (IDR Or PSLF)

Clients already pursuing PSLF generally have a relatively straightforward path under the new legislation.

Anyone currently making payments under ICR or PAYE who is eligible for New IBR should switch to that plan before July 1, 2026. The ideal timing depends on their current payment versus what their recalculated payment would be under IBR based on their most recent tax return (or alternate income documentation). If their current payment is lower, it may be worth waiting as long as possible before switching plans. In some cases, it may be beneficial to file an extension for the 2025 tax year in order to enroll using 2024's return in order to reduce a client's payment amount. Clients limited to Old IBR should consider staying on their current payment plan or switching to PAYE (if they are eligible) until they transition to Old IBR, depending on their current and future payment amounts.

Borrowers – especially those on Old IBR – should also evaluate whether switching to RAP makes sense once it becomes available. While we believe existing borrowers will be able to switch back and forth between RAP and IBR, it remains unclear whether any unpaid interest would be added back to the loan when switching, or how often a change could be made.

Regardless of repayment plan, borrowers working toward PSLF should continue submitting employer certification forms at least annually to document their qualifying employment and track eligible payments.

For clients pursuing long-term forgiveness under IDR, more evaluation will be required. RAP eliminates negative amortization by fully subsidizing unpaid interest each month, while interest continues to accrue under both Old and New IBR. Because the American Rescue Plan's provision making IDR forgiveness tax-free expires in 2025, forgiveness under IDR plans will once again be included in taxable income in the year forgiveness is achieved. That means a borrower's forgiven balance will trigger a potential tax bomb unless future legislation changes this rule. While RAP's interest subsidy helps reduce long-term balances, it requires repayment for 30 years – compared to 25 years under Old IBR and 20 years under New IBR – which can affect the overall cost of the forgiveness strategy.

It's also worth reminding clients pursuing either PSLF or IDR forgiveness to take regular screenshots of their progress. The Department of Education's forgiveness tracking tools are currently unavailable due to a lapse in the contract with the vendor that managed them. For now, loan servicers are the only ones tracking payment counts – and given past issues with tracking accuracy, it's wise for borrowers to maintain their own documentation to preserve proof of progress in case any disputes arise in the future.

The case studies below show how these principles apply to different client profiles.

Case Study #1: Mid-Career Public Service Professional With Family Obligations

This scenario introduces Chris, a married borrower in a public service role who is working toward PSLF. With a growing loan balance and household responsibilities to manage, his advisor will need to carefully weigh repayment trade-offs while keeping the family's broader financial picture in view.

- Chris is 37 years old, married, with two children.

- He owes $180,000 in law school loans. He had borrowed only $150,000, but negative amortization has increased the balance.

- His loans were taken out prior to July 1, 2014, making him eligible only for Old IBR, with payments of 15% of discretionary income.

- His AGI is $75,000 per year, and his spouse's is $150,000 per year. They filed taxes separately in 2024 in anticipation of student loan payments resuming after the SAVE plan was paused.

- Chris had accumulated 80 PSLF credits as of July 2024, when the SAVE plan was paused.

- He has not made any payments in the 11 months since.

Recommended Action:

Chris should switch to Old IBR as soon as possible to begin accruing PSLF credits again. His SAVE plan monthly payments would have been $140, but under Old IBR, he will now need to pay $453 per month for the coming year. Once RAP becomes available, switching could lower his monthly payment to $337.

As he approaches 120 qualifying payments, Chris should explore the PSLF Buyback program – if it is still available. This program, introduced in late 2023, allows borrowers to retroactively receive PSLF credit for missed months (such as those during the SAVE pause) by making a lump-sum payment equal to what they would have owed during that time. While this option is currently available, it is subject to regulatory change, and there is significant risk that the program could be discontinued in the near future.

If the buyback program is eliminated, Chris would need to make additional payments in order to make up for the additional months required.

Planning Considerations:

Because Chris and his spouse file taxes separately, his IBR payments would be based solely on his own income, rather than his combined household income. While this strategy can reduce their monthly student loan payments, filing separately can result in a higher overall household tax bill – an important trade-off to evaluate annually as income or tax law changes.

Case Study #2: A Young Private Practice Veterinarian Pursuing IDR Forgiveness

Juniper is an early-career borrower with a high student loan balance relative to her income. She's not eligible for PSLF, so her primary goal is long-term forgiveness under an income-driven plan. Her advisor will need to help her weigh the implications of staying on IBR versus switching to RAP, with close attention to loan growth, forgiveness timelines, and the impact of expected increases in income.

- Juniper is 27 and works as a veterinarian. She is single with no children.

- She has $230,000 in Federal student loans, with the first loan taken out in 2015. This qualifies her for New IBR, with payments at 10% of discretionary income and forgiveness after 20 years of payments.

- She graduated in 2023 and enrolled in SAVE after her initial grace period ended, but made only a few payments before the plan was paused.

- Her salary is $120,000 at a private practice veterinary clinic.

Recommended Action:

Juniper should enroll in New IBR, which would result in a monthly payment of $804. Once RAP allows enrollees, she'll need to choose between staying on New IBR or switching to RAP. New IBR offers a shorter timeline to forgiveness (20 years versus 30 years under RAP), and despite negative amortization, the additional 10 years of required payments under RAP would likely outweigh the benefit of a slightly lower balance.

Planning Considerations:

Although RAP would slightly reduce her loan balance (by at least $50 per month), this interest subsidy wouldn't justify the extra decade of payments. However, if Juniper expects a significant and rapid increase in income, RAP may actually be more advantageous due to its interest subsidy – especially if she ultimately plans to pay off her loan in full by eventually switching to the standard repayment plan once her income allows her to make those higher payments.

This scenario won't apply to most borrowers, but it highlights the importance of regularly reevaluating repayment strategy based on income changes.

Case Study #3: High-Income Borrower Optimizing PSLF Strategy

Rowan is a high-earning physician whose income now far exceeds his original loan balance. Because he qualifies only for Old IBR and RAP, his advisor's focus will be on the payment cap available under IBR and minimizing his total outlay and avoiding plan changes that could inadvertently increase payments or jeopardize his PSLF eligibility.

- Rowan is a doctor, now earning $450,000. He is single with no kids.

- He has a remaining loan balance of $250,000 at 6.5%. His loan balance started at $210,000 but grew over time due to negative amortization.

- He has 70 payments toward PSLF and was on the SAVE plan when it was paused.

- He had an undergraduate loan prior to July 1, 2014, making him eligible only for Old IBR and RAP.

Recommended Action:

Rowan should switch to Old IBR immediately and begin making capped monthly payments of $2,331. Since IBR limits monthly payments based on the standard 10-year repayment amount, Rowan's payment will be limited to $2,331 no matter how high his income rises, as long as he stays on IBR. Staying on Old IBR through his 120th eligible payment will result in substantial savings and full loan forgiveness through PSLF.

Planning Considerations:

RAP would result in a $3,750 monthly payment – substantially higher than the capped IBR amount – and it doesn't offer any advantages for PSLF in Rowan's case. Because PSLF is based on employment and qualifying payments rather than total repayment amount, minimizing payments while meeting eligibility is the optimal strategy in Rowan's scenario. Staying on IBR avoids unnecessary outflows while keeping on track for full loan discharge.

Considerations For Clients With Existing Parent PLUS Loans

For clients with Parent PLUS loans, a key question for advisors is whether these clients would benefit from accessing an Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plan. While some borrowers with Parent PLUS loans may be able to repay their loans without materially affecting their financial plan, others may find significant relief through income-based repayment, potentially paying a manageable amount until death, when any remaining balance would be discharged tax-free.

Accessing this strategy, however, requires action before July 1, 2026. In order to access an income-based repayment plan, borrowers will have to first consolidate their Parent PLUS loans. Once consolidated, borrowers will be able to enroll in the Income-Contingent Repayment (ICR) plan, which will eventually be converted into Old IBR. After the 2026 deadline, Parent PLUS borrowers will no longer be able to access any IDR plans – meaning this window could represent the last opportunity for them to pursue a flexible repayment strategy.

Parent PLUS loans must be consolidated before July 1, 2026, in order to access income-driven repayment.

This deadline poses a unique and significant challenge for parents of current college students who had planned to use Parent PLUS loans to finance upcoming years of their child's college education. While these parents are exempt from the new borrowing caps, taking out new Parent PLUS loans for the 2026–2027 school year would disqualify them from enrolling in IDR for the existing Parent PLUS loans – even if those loans were previously consolidated.

Advisors working with clients in this situation will need to carefully analyze the pros and cons between continuing to borrow PLUS loans, taking out new Federal or private loans in the student's name (which may require a co-signer), or taking out private loans in the parents' name. Each option has implications for repayment flexibility, long-term interest costs, and overall household balance sheet management.

Planning Considerations For Parents Of Soon-To-Be College Students

The college funding landscape for parents of high schoolers preparing for college has changed substantially. With the new $65,000 lifetime cap on Parent PLUS loans, parents now face much stricter limits on how much they can borrow – and far fewer repayment options than before.

This change is expected to drive a significant increase in the use of private student loans, whether issued through universities or third-party lenders. However, these loans may come with higher interest rates, stricter repayment terms, more limited forbearance options, and no access to PSLF or long-term forgiveness programs.

Notably, parents who take out new Parent PLUS loans will no longer be able to access Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plans. Which means the full balance of the loans they take out must be repaid over time – regardless of income or life changes.

One real-world example (shared by Ryan) illustrates how disruptive this change can be. An unmarried couple in a long-term partnership with two teenage children had planned to fund college by having the lower-earning parent – largely a stay-at-home parent with about $20,000 of earned income most years – take out Parent PLUS loans in their name. Under the old rules, those loans could have been consolidated and repaid through an IDR plan, potentially resulting in very low or even $0 monthly payments. But now, that strategy is no longer possible. With two children approaching college age (15 and 13 years old), the family is reevaluating their entire approach to paying for higher education.

With undergraduate students limited to borrowing just $27,000 over four years, and their parents now limited to $65,000, the total Federal borrowing available per undergraduate student is $92,000. Given that some schools charge close to that amount for just a single year of attendance, families without significant savings will need to either take out significant private debt with much less flexibility or rethink their college choices altogether.

This policy shift may also have a significant impact on colleges themselves, potentially resulting in program closures, tuition reductions, or institutional restructuring – consequences beyond the scope of this discussion.

After half a decade of upheaval, the student loan system appears to be entering a period of less volatility. But with this potential consistency comes confusion and a fresh set of complex decisions that borrowers will need to make. For financial advisors, this is a crucial moment: staying updated on evolving repayment rules and legislative changes allows them to offer tremendous value – both to borrowers navigating repayment and to families rethinking how they'll pay for college.

Ultimately, the key point is that proactive planning is more important than ever. Advisors who help clients understand the implications of these new rules and explore their options – before key deadlines close the door – can make a powerful difference in their clients' financial futures.