Executive Summary

Owners of IRAs and qualified retirement accounts might name a trust as the account's beneficiary for a number of reasons. They might want to have more control over how the account assets are distributed to their beneficiaries. Or they might want to protect any of their beneficiaries who qualify for means-tested public benefits. In some cases, it might simply be more convenient to name a single entity – like a trust – as the beneficiary of all their retirement accounts, so that any future changes to be made to the trust itself rather than needing to be reflected across all the owner's beneficiary designation form. Whatever the reason, naming a trust as the beneficiary of a retirement account subjects the account to a complex series of rules regarding how the account must be distributed after the owner's death.

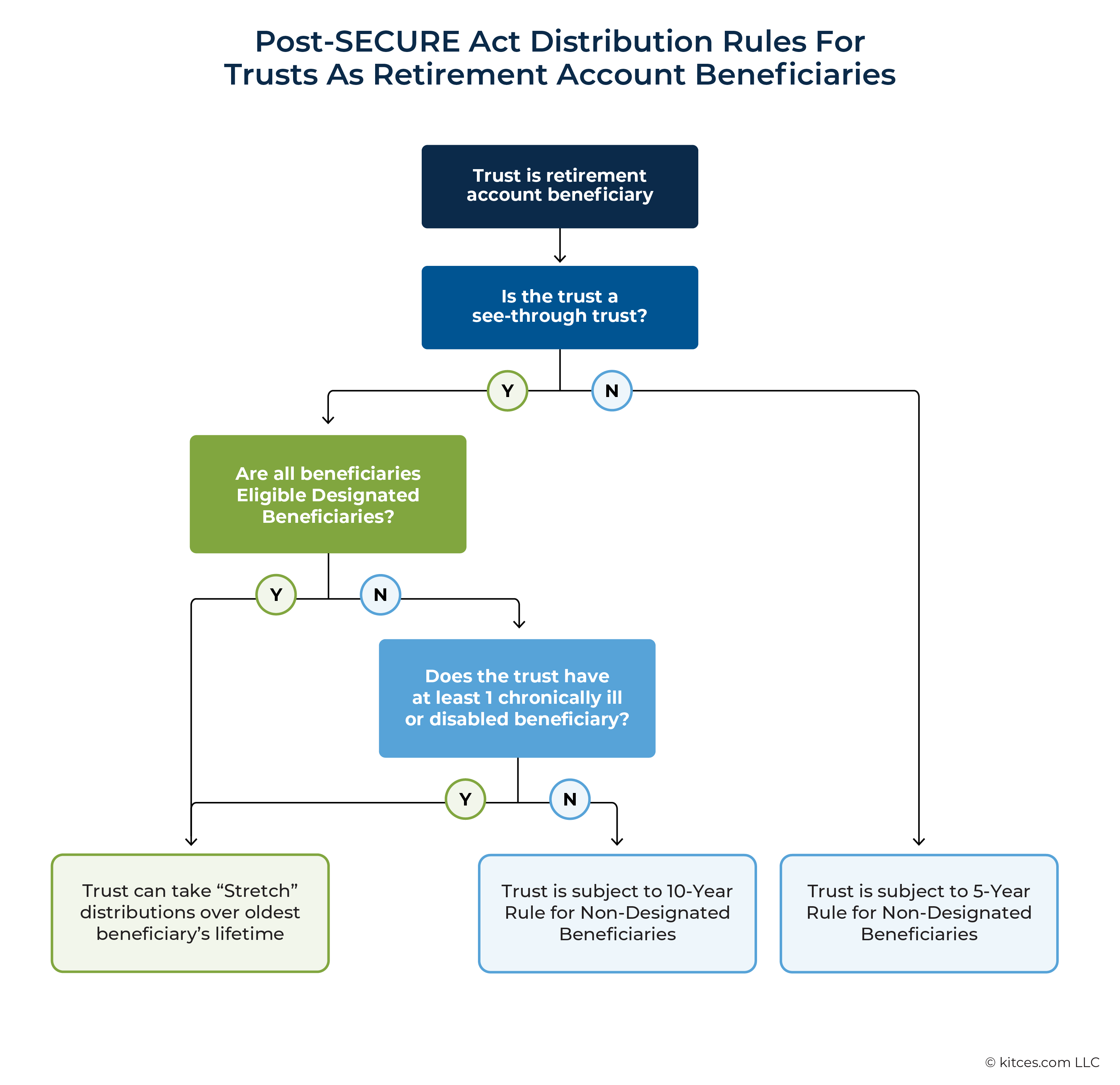

The general rule is that trusts are treated as "Non-Designated Beneficiaries" and therefore must fully distribute the retirement account by the end of the fifth year after the owner's death. However, some trusts – specifically, 'see-through' trusts whose beneficiaries all consist of identifiable individuals – can qualify for the more favorable distribution schedules available to Designated Beneficiaries. The caveat is that no matter how many beneficiaries the trust has, the entire trust will generally be treated as a single beneficiary for distribution purposes. That means the distribution schedule is typically based on the least favorable treatment among all of its individual beneficiaries. If all of the trust's beneficiaries are considered Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, the trust may take 'stretch' distributions based on the life expectancy of the oldest beneficiary. But if even one of the trust beneficiaries is a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary, then the entire trust is subject to the 10-Year Rule and must be fully distributed by the end of the tenth year after the account owner's death.

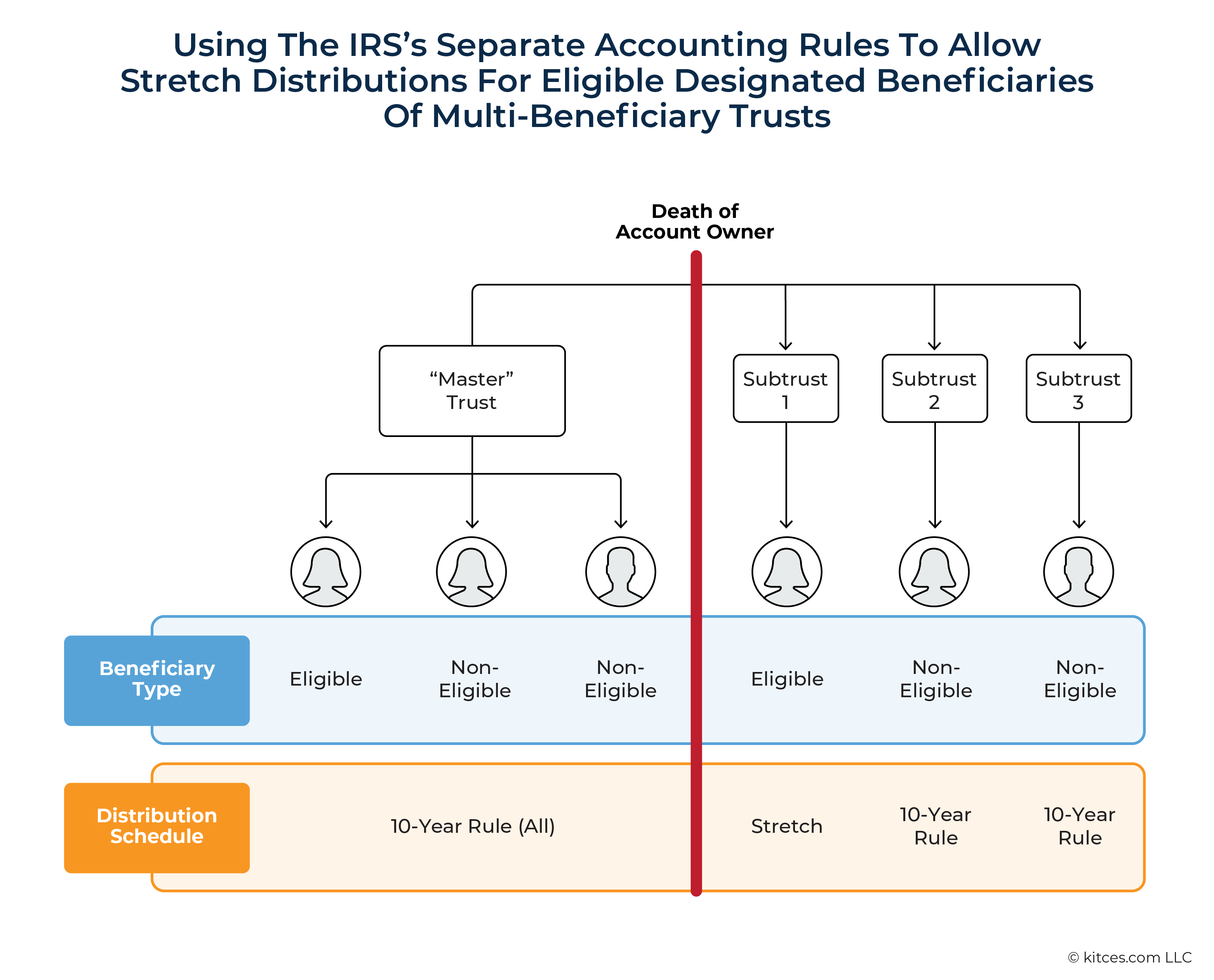

When the IRS released its Final RMD Regulations in July of 2024, it introduced a significant new carve-out to the 'single distribution schedule' rule. Under the new rules, if a see-through trust is split into separate subtrusts immediately following the account owner's death, each subtrust can use its own distribution schedule. In other words, under the old rules, a trust with a mix of Eligible and Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries would have been automatically subject to the 10-Year Rule for Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries. Under the new rule, if the trust is divided into separate subtrusts for each beneficiary, the Eligible Designated Beneficiaries can each receive "stretch" distributions over their own life expectancy – while only the Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries will be subject to the 10-Year Rule.

Notably, the IRS regulations only allow this 'separate accounting' treatment when the trust document includes a provision to divide the trust into separate subtrusts before the account owner's death. The trust document must also specify how the retirement account is to be allocated among the individual subtrusts– the trustee cannot be granted discretion to make those decisions after the fact. Additionally, the trust must already qualify as a see-through trust; otherwise, any non-individual beneficiaries will cause the entire trust to be considered a Non-Designated Beneficiary, regardless of whether it's divided into separate subtrusts after the owner's death.

Ultimately, the new "separate accounting" rule creates more flexibility for retirement account owners who want to name a trust as their account beneficiary while still optimizing the tax treatment of distributions for each of the trust beneficiaries. Under the new rules, retirement plan owners with beneficiaries who are both Eligible and Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries can ensure that their Eligible Designated Beneficiaries can still receive stretch distribution treatment. But because the provision to divide the trust must be written into the trust document itself, it's important for advisors to work with their clients (and their estate attorneys) to implement any necessary changes in advance!

Post-SECURE Act Rules For Trusts As Retirement Account Beneficiaries

In July 2024, the IRS released a set of Final Regulations that clarified many of the outstanding rules for IRAs and qualified retirement accounts following the passage of the original SECURE Act in 2019. While the bulk of the attention surrounding the Final Regulations focused on their confirmation that certain account beneficiaries subject to the SECURE Act's 10-Year Rule would be required to take annual Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) after the account owner's death, the regulations also introduced a number of new affecting retirement accounts with trusts named as beneficiaries.

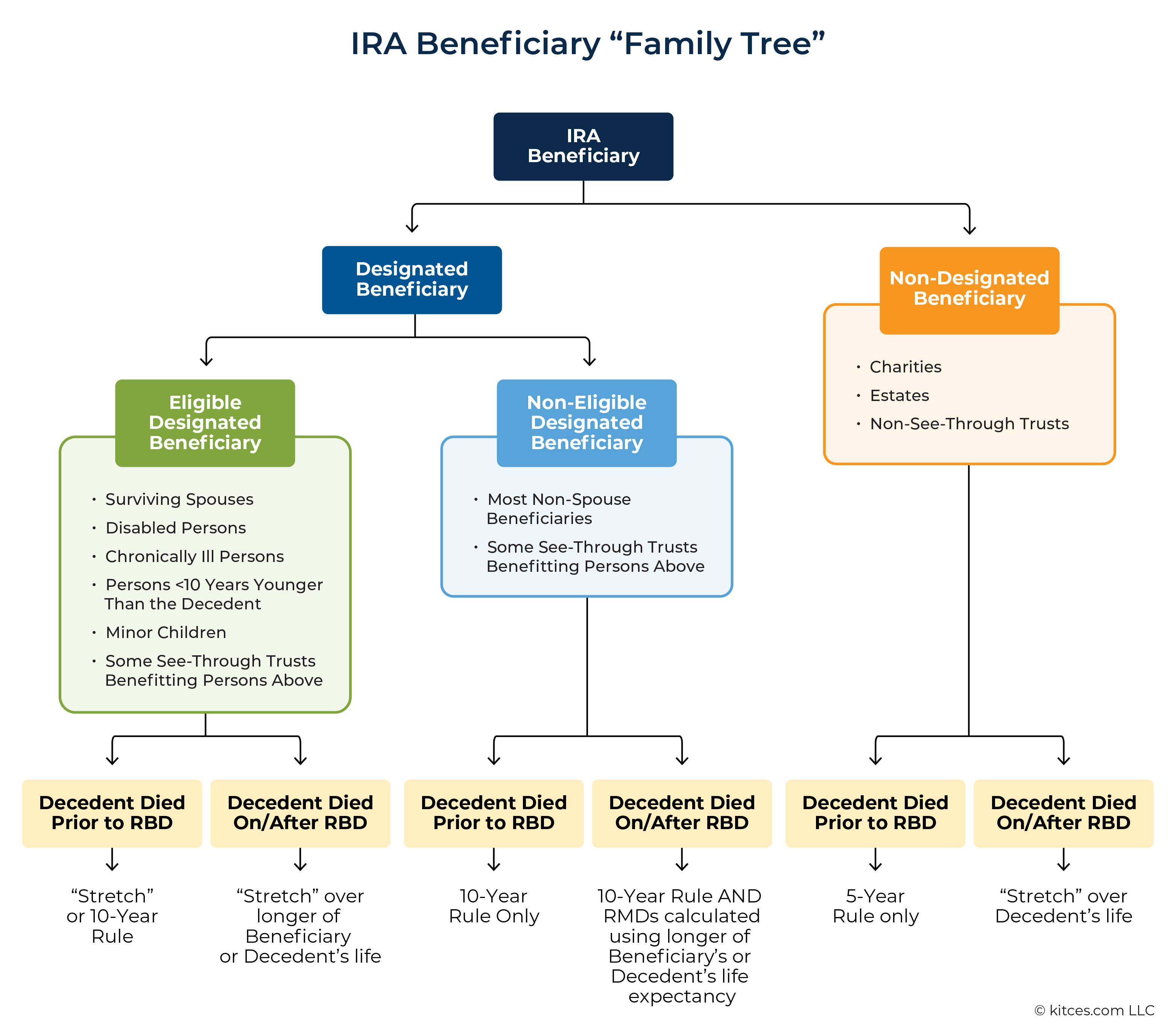

When the owner of an IRA or qualified retirement account passes away, the account's beneficiaries become subject to a complex series of rules governing how the account must subsequently be distributed based on the identity of the beneficiary. Any beneficiary that is not an individual person (e.g., charitable organizations, the owner's estate, and trusts) is considered a Non-Designated Beneficiary. If the owner died before their Required Beginning Date (RBD), these accounts must be fully distributed by the end of the fifth year after the original owner's death. If the owner died after their RBD, the beneficiary may take annual 'stretch' distributions based on the deceased account owner's life expectancy.

By contrast, individual Designated Beneficiaries generally receive more favorable distribution treatment, though the specific rules depend on how the beneficiary is classified. Eligible Designated Beneficiaries – including spouses, people who are disabled or chronically ill, minor children, and anyone less than 10 years younger than the decedent – may 'stretch' distributions over their own life expectancy (or the longer of theirs or the decedent's life expectancy, if the decedent died on or after their RBD). Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries – i.e., those who don't meet the Eligible Designated Beneficiary criteria – are subject to the 10-Year Rule, which requires the account to be fully distributed by the end of the tenth year after the account owner's death (with RMDs also required in each year of the 10-year window in cases where the decedent passed away on or after their RBD).

The chart below summarizes how different types of beneficiaries are treated under post-SECURE Act rules, based on their classification and the timing of the account owner's death.

When a trust is named as the beneficiary of an IRA or employer retirement account, however, the rules get even more complex.

The general rule is that, as noted above, a trust is considered a Non-Designated Beneficiary, meaning that the trust has until the end of the fifth year after the owner's death to fully distribute the account. But because trusts generally pay higher effective tax rates on their income because of the compressed tax bracket structure to which they're subject, leaving a retirement account to a trust subject to the 5-Year Rule can have disastrous tax consequences: With only six tax years (i.e., the year of death plus five) to distribute the account, there's only so much that's possible to spread out the tax impact, particularly with large pre-tax accounts.

However, the IRS has carved out significant exceptions to the general rule that treats trusts as Non-Designated Beneficiaries. Specifically, Treas. Reg. Section 1.401(a)(9)–4(f)(1) states that the beneficiaries of a 'see-through' trust are treated as Designated Beneficiaries. A see-through trust is defined as one that:

- Is valid under state law;

- Is irrevocable (or becomes irrevocable on the owner's death);

- Has beneficiaries who are 'identifiable' (i.e., can be identified as a specific person); and

- Meets the requirement to provide trust documents to the plan administrator by October 31st of the year following the owner's death (although this rule only applies to employer plans, not IRAs).

When a trust meets these criteria, it's no longer treated as a Non-Designated Beneficiary subject to the 5-Year Rule. Instead, its distribution rules depend on the identity/ies of the underlying trust beneficiaries.

When the trust has only a single beneficiary, the trust is simply subject to the distribution rules that would have applied if the beneficiary had inherited the account directly – i.e., eligible for stretch distributions if the trust beneficiary would qualify as an Eligible Designated Beneficiary, or subject to the 10-Year Rule if the trust beneficiary would have been a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary.

Example 1: Lorelai is the owner of a $5 million IRA. She names a trust as the IRA's beneficiary, and the trust's sole beneficiary is Lorelai's adult daughter, Rory.

Since Rory is an identifiable individual, the trust qualifies as a see-through trust (assuming it meets the other applicable requirements). If Lorelai dies, then the trust will be subject to the same distribution rules that Rory would have been subject to if she had been directly named as the IRA beneficiary.

Since Rory is a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary, the trust is subject to the 10-Year Rule, rather than the 5-Year Rule that would have applied if it weren't a see-through trust. In other words, Rory has effectively 11 years (the year of Lorelai's death, plus the next 10) over which to spread out distributions, rather than just 6.

Distribution Rules When A Trust Has Multiple Beneficiaries

While the rules are fairly straightforward for IRA distributions to a see-through trust when it only has a single beneficiary, the rules become more complex when the trust has multiple beneficiaries. Which is very often the case, since often the point of naming trusts as account beneficiaries is to be able to name a series of successors who will inherit the account's remaining funds after the original owner's death.

Nerd Note:

The terminology around trust and retirement account beneficiaries can get somewhat confusing. For example, the term "beneficiary" might refer to someone named directly on a retirement account, or to someone designated as a trust beneficiary – and, in some cases, a trust beneficiary might not be considered a retirement account beneficiary, and vice versa (as will be discussed later).

To reduce confusion, this article will clarify, where applicable, whether "beneficiary" refers to a beneficiary of the retirement account or the trust.

In addition, the same post-death distribution rules apply to both IRAs and employer retirement plans in most cases. However, there are some rare exceptions where the rules differ. For simplicity, IRAs and employer plans will be discussed together in this article unless different rules apply to each type of plan.

In general, the rules for retirement account distributions to a see-through trust with multiple beneficiaries are the same as those that apply to an account with multiple direct beneficiaries. Under Treas. Reg. Section 1.401(a)(9)–5(e)(2)(i), if any of the account's beneficiaries are considered Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, the account is treated as having no Eligible Designated Beneficiaries. As a result, the entire account is subject to the 10-Year Rule that applies to Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries and must be fully distributed by the end of the 10th year after the owner's death.

Additionally, under Treas. Reg. Section 1.401(a)(9)–5(f)(1)(i), all Designated Beneficiaries are required to follow a single distribution schedule based on the life expectancy of the oldest beneficiary. This means that, to the extent that the beneficiaries must take RMDs from the retirement account (because the original owner had reached their RBD before their death), they must all follow the same schedule based on whichever beneficiary is oldest.

In essence, then, when a see-through trust with multiple beneficiaries is named as the beneficiary of a retirement account, two main factors determine how the trust will be required to take post-death distributions from the account:

- Whether the trust has any Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (in which case the 10-Year Rule applies to the whole trust); and

- The age of the oldest beneficiary (which determines the life expectancy used to calculate RMDs taken by the trust, if applicable).

However, as is often the case in anything tax-related, there are nuances and exceptions to the general rules that deserve a deeper look.

The IRS's New Separate Accounting Rule For Trusts Divided On The Death Of The IRA Owner

Since the passage of the SECURE Act in 2019, there have only been two exceptions to the "single distribution schedule" rule for see-through trusts with multiple Designated Beneficiaries.

The first is when at least one of the trust's beneficiaries is a person who is chronically ill or disabled. Congress created this carve-out in the SECURE Act to protect individuals who qualify for means-tested public benefits, such as Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Medicaid, and who often use trusts to hold assets to fund their healthcare and living expenses while preserving their eligibility for benefits.

As noted above, retirement account beneficiaries who are chronically ill or disabled are considered Eligible Designated Beneficiaries and are allowed to take stretch distributions over their life expectancy. However, under the "single distribution schedule" rule, a trust with a beneficiary who is chronically ill or disabled would become subject to the 10-Year Rule if there is even a single other trust beneficiary who doesn't qualify as an Eligible Designated Beneficiary – which the majority of special needs trusts do, if only to designate an individual to distribute the remaining assets to if the original beneficiary passes away. As a result, Congress made a rule to exempt such trusts from the normal trust beneficiary rules.

As codified under IRC Sec. 401(a)(9)(H)(iv)–(v), this exception applies only to a specific type of trust called an Applicable Multi-Beneficiary Trust (AMBT). An AMBT is a trust that:

- Has two or more Designated Beneficiaries (i.e., are individual people and not other trusts, though charitable organizations are allowed as remainder beneficiaries as codified in the SECURE 2.0 Act); and

- Includes at least one beneficiary who is chronically ill or disabled.

According to the law, if the terms of the trust provide for it to be divided into separate subtrusts for each beneficiary upon the death of the IRA owner, then each trust beneficiary may use their own distribution schedule to determine post-death distributions. Which means that the presence of a beneficiary who is disabled or chronically ill (and is, by definition, an Eligible Designated Beneficiary entitled to stretch distributions over their life expectancy) can allow more favorable treatment for their portion of the trust – even if other beneficiaries are Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries.

The second exception to the "single distribution schedule" rule for trusts occurs when a trust is divided into separate see-through subtrusts for its beneficiaries, and each subtrust is named directly as a beneficiary on the IRA owner's beneficiary designation form. Treasury regulations have long allowed a plan with multiple directly named beneficiaries to be divided into individual accounts for each beneficiary, with each subject to their own individual distribution schedule. However, the IRS has historically not allowed the same treatment for beneficiaries of a trust named as the sole beneficiary of a retirement plan.

When the IRS released its Proposed Regulations relating to the SECURE Act in 2022, it explicitly prohibited the application of individual distribution schedules for trust beneficiaries – except in the sole case of AMBTs. As a result, beneficiaries of a non-AMBT trust could only use their own distribution schedules if their specific portion of the trust was named directly as a beneficiary of the retirement plan.

This rule often caused planning headaches, however, because it undermined one of the main benefits of naming a trust as a retirement account: administrative simplicity. If each beneficiary's subtrust had to be named on the plan owner's beneficiary designation form in order to use a separate distribution schedule, then any future changes to the trust or its subtrusts would also require updating the beneficiary designation form.

Yet, the whole point of using a trust as the retirement account beneficiary in the first place is often to ensure that changes to the owner's wishes can be made in a single place – the trust itself – without needing to coordinate amendments across multiple documents. Under the old rules, however, simply designating the 'master' trust as the account beneficiary effectively forced all beneficiaries to use a single distribution schedule based on the least favorable distribution period – unless the trust qualified as an AMBT due to the presence of a beneficiary who is chronically ill or disabled.

IRS Final Regulations Allow Separate Accounting For All See-Through Trusts

When the IRS published its final RMD regulations in 2024, it completely reversed its position on the treatment of trusts with multiple beneficiaries. Rather than allowing individual distribution schedules only for AMBTs (and requiring a single distribution schedule for all other trusts), Treas. Reg. Section 1.401(a)(9)–8(a)(iii)(B) of the Final Regulations allows separate distribution schedules for each trust beneficiary in any trust that is divided into separate subtrusts after the death of the original IRA owner (provided the trust meets certain other requirements, as described below).

In other words, it's no longer necessary for a trust to include a beneficiary who is chronically ill or disabled, or for subtrusts to be named directly on the beneficiary designation form, in order to apply separate distribution schedules to each beneficiary. As long as the trust is divided into separate subtrusts for each beneficiary upon the death of the account owner and meets the rules described in more detail below, each beneficiary is subject to their own individual distribution schedule, regardless of the status of the other beneficiaries.

To use the new 'separate accounting' rules, however, a trust must meet certain requirements laid out in the Final Regulations.

First, the 'master' trust named as the retirement plan beneficiary must be a see-through trust. This means that all beneficiaries must be 'identifiable' as individuals; generally, the trust cannot include non-individual beneficiaries such as charities. However, some non-identifiable trust beneficiaries may be disregarded for distribution purposes – such as 'successor' beneficiaries of a Conduit Trust or 'third-in-line' beneficiaries of a Discretionary Trust – without jeopardizing the trust's see-through status.

Nerd Note:

The SECURE 2.0 Act slightly loosened the see-through trust requirements for Applicable Multi-Beneficiary Trusts (AMBTs) with at least one beneficiary who is chronically ill or disabled. Specifically, naming a qualified charity as a successor beneficiary to that individual will not disqualify the trust from taking stretch distributions.

Second, the trust must specifically state that it will be immediately divided as of the death of the retirement plan owner, and that the master trust will be terminated as of that date. In other words, the decision to divide the trust can't be made by the trustee after the owner's death; it must be explicitly provided for in the trust document itself.

Notably, the Final Regulations do allow for some administrative delay between the plan owner's death and the actual division of the trust. For example, tax filings or payments of final expenses may need to occur before the master trust is formally terminated. However, if there is a delay, the trustee must allocate "all post-death gains and losses, contributions, forfeitures, and expenses for the period prior to the establishment of the separate accounts" on a pro rata basis among the subtrusts once the division is complete.

Additionally, the regulations require that there be "no discretion as to the extent of which the separate trusts' post-death distributions… are allocated". The trust document must clearly specify how the account assets are to be divided – the trustee cannot decide how to allocate distributions after the fact.

Finally, the IRS regulations don't require that each beneficiary have their own subtrust in order to qualify for separate accounting treatment. The rule only requires that, if the trust does divide into subtrusts (and all the above conditions are met), each subtrust will effectively be treated as its own see-through trust, with distribution rules applied separately to each trust.

For example, consider a see-through trust with 10 beneficiaries – one Eligible Designated Beneficiary and nine Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries. Rather than splitting into 10 separate subtrusts, the trust can instead divide into two: one subtrust for the Eligible Designated Beneficiary as sole beneficiary (who can take stretch distributions since that subtrust has no Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries), and a second subtrust for all nine Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries as its beneficiaries (who would be subject to the 10-Year Rule regardless).

Planning Impact Of The IRS Regulations On Multi-Beneficiary Trusts

Prior to the IRS regulations, there were other ways to structure trust terms to preserve stretch distributions for Eligible Designated Beneficiaries while including some Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries.

For example, when a trust is structured as a Conduit Trust – where all retirement account distributions made by the trust are required to be passed on to the trust's beneficiaries each year – any 'secondary' beneficiaries entitled to receive trust assets only after the death of the 'primary' income beneficiaries are disregarded for retirement account distribution purposes. So, if an Eligible Designated Beneficiary is required by the trust terms to receive all retirement account distributions, the trust can still take stretch distributions over that beneficiary's lifetime, even if the secondary beneficiaries are Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (or even Non-Designated Beneficiaries, such as charitable organizations) – because the "single distribution schedule" rule only applies to the primary income beneficiary.

Additionally, even if the trust isn't set up as a Conduit Trust, Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries may still be disregarded for distribution purposes as long as they meet one of two exceptions:

- They are 'third in line' (i.e., they would receive trust assets only after the death of a secondary beneficiary); or

- They are entitled to receive assets only after the death of a primary beneficiary, and that primary beneficiary must receive full distribution of trust assets by no later than the year of their 31st birthday.

As long as the trust is structured so that the only retirement account beneficiary who counts is an Eligible Designated Beneficiary, the trust can still qualify for stretch distributions – without needing to split into separate subtrusts.

However, both of these strategies require giving the Eligible Designated Beneficiaries a higher income priority than the Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries. Not just that, but they effectively bar the Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries from receiving any of the retirement plan assets until after the death of the Eligible Designated Beneficiaries. If the retirement plan owner wanted to give any Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries earlier access to the plan funds, the only options were:

- Naming those beneficiaries directly on the beneficiary designation form; or

- Subjecting the entire trust to the 10-Year Rule.

The new option to create separate subtrusts with their own individual distribution periods now changes this dynamic significantly. Retirement plan owners can give immediate access to plan funds to Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (subject to the 10-Year Rule) without jeopardizing lifetime stretch treatment for Eligible Designated Beneficiaries.

As a result, this planning flexibility may be especially valuable in situations where the retirement account is left to a mix of Eligible and Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries – and the goal is to grant immediate access to the plan funds for all parties while optimizing the tax impact of the required distributions for each beneficiary.

Example 2: Claire is 60 years old and has a $1 million 401(k) plan. If she passes away, she wants to leave 50% of the account to her husband, John, and 25% each of her two children from a previous marriage, Brian (age 25) and Allison (age 23).

She wants to ensure that if John passes away after her, any remaining amount from his share will go to her children. And if all three pass before the funds are fully distributed, she wants any remaining funds to go to her favorite charity, the Humane Society.

Claire establishes a trust and names it as the beneficiary of her 401(k) plan. The terms of the trust state the following:

- 50% of the account will be allocated to John.

- 25% will go to Brian and 25% to Allison.

- Brian and Allison are equal successor beneficiaries to John's 50% share of the trust.

- The Humane Society is the successor beneficiary in case all three parties die before the funds are distributed.

Under the old rules, the presence of Non-Eligible Designated Beneficaries (Brian and Allison) meant the entire trust would be subject to the 10-Year Rule.

Even worse, however, is that if the trust were set up as a Discretionary Trust (i.e., allowing distributions from the retirement account to accumulate rather than requiring them to be immediately distributed), the Humane Society's presence as a successor beneficiary could have caused the entire trust to be treated as a Non-Designated Beneficiary, meaning that the whole retirement account would be required to be emptied by the end of the fifth year after Claire's death!

Under the old rules, it would have been difficult for Claire in the example above to accomplish all of her goals in a tax-efficient way. She could have named the individual beneficiaries directly on her beneficiary designation form, but that would have lost the ability to direct who would receive her retirement funds if the original beneficiaries passed away before the plan was fully distributed. She could have named separate trusts directly as beneficiaries, but that would have required syncing trust amendments with beneficiary designation updates. And she could have left her single trust in place as is, but that would have potentially triggered the whole $1 million to be distributed within five years of her death, creating a big tax bite from so much being distributed all at once.

However, under the new IRS regulations, the use of separate subtrusts for Eligible and Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries can ensure that any Eligible Designated Beneficiaries are still able to receive stretch distributions – while also mitigating the tax impact of having to distribute the entire account within 10 years.

Furthermore, the subtrusts can take advantage of the applicable rules for Conduit and Discretionary Trusts to ensure that successor beneficiaries entitled to trust assets after the death of a primary beneficiary don't trigger adverse tax consequences for the entire trust.

Example 3: After the new IRS regulations were released, Claire, from the example above, met with her estate attorney to add language to the trust specifying that it is to be immediately divided into three separate subtrusts upon her death: the John Subtrust, the Brian Subtrust, and the Allison Subtrust. The 'master' trust document provides that 50% of Claire's retirement account proceeds will be allocated to the John Subtrust, and 25% each to the Brian and Allison Subtrusts.

The John Subtrust specifies that all 401(k) plan distributions received by the trust will be passed to John in the same year they're received. If John dies, Brian and Allison would each be entitled to 50% of the remaining distributions.

The Brian and Allison Subtrusts specify that Brian and Allison may receive the proceeds of any retirement distributions to their respective trusts, but the trustee has discretion over whether and how to distribute the funds. Brian and Allison are named as each other's successors, and the Humane Society is the contingent beneficiary.

Because the updated trust language requires the trust to be divided into separate subtrusts immediately upon Claire's death and clearly allocates percentages to each subtrust, each is treated separately for RMD purposes:

- John's subtrust qualifies as a Conduit Trust because it requires all 401(k) plan distributions to be passed on to John in the same year they're received. Which means that only the primary income beneficiary – and none of the successor beneficiaries – are considered in determining the distribution period. Since John (as Claire's spouse) is an Eligible Designated Beneficiary, his subtrust can take stretch distributions from the 401(k) plan, or, under the special rules for spousal beneficiaries, defer RMDs until the year Claire would have been required to begin them.

- Brian and Allison's subtrusts are Discretionary Trusts because they may – but are not required to – receive distributions from their respective subtrusts. Which means the distribution period is based on both the primary and first successor beneficiaries (while disregarding any 'third-in-line' beneficiary and beyond). Since Brian and Allison serve as each other's successor, the Humane Society (as the third-in-line beneficiary) is disregarded. As a result, while the Brian and Allison Subtrusts are subject to the 10-Year Rule (since both are Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries), they still qualify for see-through trust treatment because the Humane Society is ignored as a beneficiary for purposes of the retirement account.

As the above example shows, applying separate accounting treatment allows planners to segregate different beneficiaries from each other to optimize the tax treatment for each type of beneficiary.

For John's subtrust, a Conduit Trust makes sense because it requires all retirement plan distributions to be passed on to John each year. As Claire's spouse, John won't be required to take any distributions until the year that Claire would have reached her RMD age, which can help defer income taxes. Additionally, the Conduit Trust allows Claire's children to serve as successor trust beneficiaries without eliminating the trust's ability to make stretch distributions.

Meanwhile, the Discretionary Trust treatment makes sense for Brian and Allison's subtrusts, since Brian and Allison are Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries already subject to the 10-Year Rule. Claire can give the trustee greater discretion over how and when Brian and Allison are allowed to take distributions.

Trusts With Retirement And Non-Retirement Assets

One of the main drawbacks of the new separate accounting rule is that it allows for no discretion in how retirement funds are allocated among subtrusts after the original owner's death. The amounts or percentages must be specified in the trust document ahead of time. Which means there's no flexibility to divide retirement accounts based on which beneficiary would have the most favorable tax outcome.

For instance, suppose a retirement account owner has two children – one in the 12% Federal tax bracket and one in the 33% bracket. Assuming the account is 100% in pre-tax dollars, it would be worth more on an after-tax basis to the child in the 12% tax bracket, since that child would pay less tax when receiving the distribution. But that kind of tax disparity won't always be apparent when a retirement account owner is drafting their trust – and even if it is, circumstances could always change between the time the trust is drafted and the account owner's death. As a result, there's little ability to plan the allocation of retirement assets based on the beneficiaries' relative tax profiles.

However, this 'no discretion' rule only applies to retirement assets held by the trust. For all other types of assets – including cash, real estate, and taxable investments – there are no restrictions on how much discretion the trustee may be granted. So, if there's a big discrepancy between the amount of tax that different beneficiaries will owe on the retirement assets they receive (which can't be avoided since the trust document must specify how much will be allocated to each account), the trustee could be instructed to offset the difference by using other (non-retirement) assets that are also held in the trust.

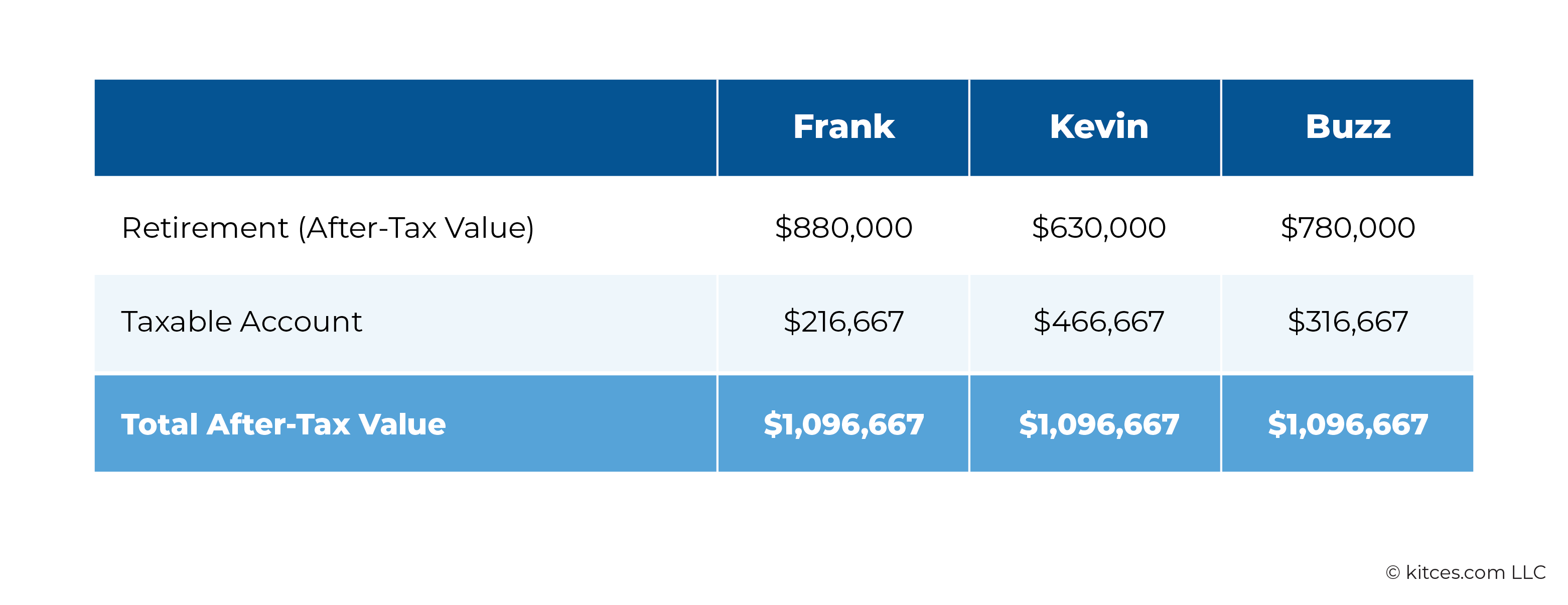

Example 3: Peter owns a $3 million IRA (in pre-tax dollars) that he wants to leave to his brother Frank and his two children, Kevin and Buzz, via a trust with separate accounting treatment to preserve Frank's Eligible Designated Beneficiary status. Peter also owns a $1 million taxable investment account that would also be left to the trust.

Frank is in the 12% Federal tax bracket, Kevin is in the 37% bracket, and Buzz is in the 22% bracket. If Peter's trust specifies that each beneficiary is to receive 1/3 of the IRA, they'd each receive $1 million on a pre-tax basis. However, their after-tax values would differ as follows:

- Frank: $1 million × (1 – 0.12) = $880,000

- Kevin: $1 million × (1 – 0.37) = $630,000

- Buzz: $1 million × (1 – 0.22) = $780,000

Since the trustee cannot alter the IRA allocations, the discrepancy in tax impact between each beneficiary can be resolved by splitting the $1 million taxable account in a way that brings each beneficiary's after-tax value to the same level.

The cumulative after-tax value of both the retirement and non-retirement assets is $880,000 (Frank's share) + $630,000 (Kevin's share) + $780,000 (Buzz's share) + $1 million (the taxable account) = $3,290,000.

Therefore, each beneficiary should receive $3,290,000 ÷ 3 = $1,096,667 total on an after-tax basis. Which means that the taxable account is distributed as follows:

- Frank: $1,096,667 − $880,000 = $216,667

- Kevin: $1,096,667 − $630,000 = $466,667

- Buzz: $1,096,667 − $780,000 = $316,667

Although the trustee of Peter's trust can't be given discretion on how to split up the retirement assets, they can be allowed discretion in allocating the taxable account to make up for the difference in tax impact.

When drafting trusts that rely on the separate accounting rules, then, clients and advisors will need to ensure that any discretionary authority granted to the trustee applies only to non-retirement funds. Many template-based trust documents may not include language reflecting the new regulations, so it's essential to work closely with an estate planning attorney to draft the trust properly.

The main impact of the IRS's new 'separate accounting' rules is that they offer significantly more flexibility when naming trusts as retirement plan beneficiaries, while retaining some ability to optimize the distribution requirements for each individual beneficiary. This can be a valuable planning tool when both Eligible and Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries are involved, since it allows the Eligible Designated Beneficiaries to retain the 'stretch' RMD treatment that spreads out distributions from the account over their remaining life expectancy. Which allows more assets to remain in the account growing tax-deferred over a longer period, ultimately increasing the amount passed on to the account owner's beneficiaries on an after-tax basis.

Leave a Reply