Executive Summary

Given the industry’s growing focus on delivering financial advice in the best interests of their clients and not ‘just’ selling them financial products, financial advicers are increasingly wary about associating their practices with “sales” techniques. However, the reality is that even those in the business of advice (and not product sales) who are confident their services are of great value to clients must still bring prospects to the door and convince them to hire the advisor and pay for that advice. Which means regardless of how knowledgeable or capable an individual advisor may be, or how well their expertise may fit a client’s needs, getting a prospective client to commit requires both expertise and persuasion.

In his book Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, Robert Cialdini presents research that helps demonstrate how advisors can leverage three simple influence tools to better aid (and retain!) clients who may already be coming to an advisor for answers but still need a nudge to actually engage the advisor… ultimately allowing advisors to save time and help more people.

First, creating a perception of scarcity around what a financial advisor offers can crystalize the value of the advisor and motivate clients to action. One way this can be done is to use a scheduling approach that involves “surge meetings”, where advisors schedule prospects and clients in a very structured and condensed time period (and not offering meeting slots outside of those ‘scarce’ time windows). Not only is this helpful to free up time for the advisor to focus on firm infrastructure and other priorities, but the apparent scarcity of available meetings tends to discourage prospects who aren’t ready to commit to working with an advisor from signing up, yet motivates clients who are ready to sign up for coveted meeting slots to take action. Which means that the people with whom advisors meet are much more likely to be ready to act in concrete ways and implement recommended changes.

Cialdini also proposes the idea of consistency, whereby individuals tend to strive for behavior that aligns with how they identify themselves. Thus, if a client views themselves as a proactive doer (opposed to a passive drifter), they are much more likely to commit to taking action – and advisors can leverage the client’s tendency to behave consistently with their ideal self-image by speaking directly to ‘doers’ in their marketing. Additionally, a goals-based planning approach can be a powerful motivator by helping clients identify their financial planning priorities, such that they feel ‘compelled’ to follow through on their financial planning recommendations to ensure their behaviors will align with their ideal future self-image.

Finally, advisors can use reciprocity as a way to persuade prospects to become clients and ultimately build the advisor’s business. Letting prospects test-drive the client experience (by offering a free preview of available planning services) can attract prospects and increase referrals, as this gesture of reciprocity can demonstrate the advisor’s value and skill by offering a clear example of what is actually delivered to clients. Exactly what is given away to prospects, and how, is up to the individual advisor, but treating a prospective client as if they have already joined the team is a great way to ensure that they actually do join the team!

Ultimately, it is important to remember that clients investigate and hire financial advisors because they want help to reach their goals. Advisors who are client-focused and have a good advice service to market can benefit from using Cialdini’s principles to persuade potential clients who would benefit from their help to take the leap into hiring them. By using Cialdini’s research to adapt strategies for use with clients, financial advisors can remove some of the resistance that prospects may initially feel by promoting trust, allowing clients to realize the reason that they sought out a financial advisor in the first place!

It’s March 1, 2020, and my wife’s school, where she teaches kindergarten, has been indefinitely canceled. My two-year-old daughter’s school is canceled shortly thereafter. As my firm’s meetings shift online, the house is getting crowded. By March 31, we were meeting with a realtor named Maria Bowman to discuss the possibility of listing our home and buying a bigger one.

We were hesitant to have this initial meeting for a number of reasons. For one thing, the stock market had just taken a 30% hit and, therefore, my income had suffered, too.

But three months later, we had sold our house through Maria and were sitting in our new home. The bad news: We paid more than 125% of our original budget. And while I don’t know if Sotheby’s is training its agents using the decision-making research conducted by marketing and psychology professor Robert Cialdini, in hindsight, most of his principles of persuasion were indeed present in our buying-and-selling process. This article is not about convincing prospects to pay more than they planned for your services. Rather, this article is intended for fiduciary planners who celebrate the positive impact they have on their clients’ lives; it is meant to help level the playing field for those advisors who may not have sales training, but know their prospects would be better off by signing on the dotted line.

There is an entire body of research on persuasion that financial planners can use to turn prospects into clients. Cialdini’s Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion identifies six shortcuts that we use as human beings to make decisions without having to evaluate all possible information. Recognizing that sometimes we won’t even have all the information available, other times we don’t have the time and capacity to get all the information, and, in some cases, it’s simply more expedient to move to a decision quickly. These shortcuts can be used to help move prospects to buyers.

There is an entire body of research on persuasion that financial planners can use to turn prospects into clients. Cialdini’s Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion identifies six shortcuts that we use as human beings to make decisions without having to evaluate all possible information. Recognizing that sometimes we won’t even have all the information available, other times we don’t have the time and capacity to get all the information, and, in some cases, it’s simply more expedient to move to a decision quickly. These shortcuts can be used to help move prospects to buyers.

Now, I know what many advisors may be thinking: “I don’t work in sales. I don’t want to trick people into saying yes.”

In fact, Cialdini addresses this in the epilogue of his book where he discusses the risks of salespeople using these persuasion techniques to manipulate consumers. So, I ask you: Do you think you provide a good service? Do you think your clients are better off with you than without you, even after they pay you? Do you sometimes find that even though your clients would be better off with you, they still need a little help to get to the decision to work with you?

If you answered “yes” to the previous questions, read on. By learning to persuade more effectively those people who can actually benefit from what you have to offer, your positive impact will ultimately be greater and more widespread. But if you answered “no” to the above questions, stop reading. Instead, I’d simply suggest that you consider quitting your current job, and either finding a new firm or starting one on your own… because if you’re not proud of the service you provide to your clients – enough to feel compelled to want more of them to benefit from it – that’s a separate problem, but one that needs to be addressed first!

I should have mentioned previously that I am happy in my new home. And, while I spent substantially more than I had expected to, I have zero regrets about the process that Maria used as our agent. In fact, I have recommended her to two friends, who have since completed similar transactions with her.

In other words, whether Maria was intentionally trying to influence us or not, I am happy that she did so, because her solution was good! The principles of persuasion that Robert Cialdini identified in his research appeared throughout these transactions, and by understanding how they work, financial advisors can implement them to enhance and improve their sales processes.

The Perception Of Scarcity Can Motivate Clients To Take Action

It’s the middle of April, and the house we have toured a few times is still on the market. Until one day it isn’t. My wife is upset, and we start to highlight all the qualities of this house that don’t exist in the other available listings. It backs up to federal land. That third floor is a perfect play space for Vivian.

To make a long story short, the buyer of our ‘dream home’ ended up getting laid off due to COVID. The house came back on the market, and we jumped at the opportunity. It wasn’t until we had the house taken out of our reach that our beliefs about the quality and rarity of this home were realized. It wasn’t until we were told that we couldn’t have it that we decided we had to have it.

Robert Cialdini would have attributed at least some of our motivation to scarcity. This is the idea that those things that are harder to acquire must be of higher quality. He states that “we often use an item’s availability to quickly and correctly decide on its quality.”

It is easy to see this applied all over the internet. For example, Taft, a fast-growing men’s shoe company, often sells out of its most popular styles. When you visit the website, Taft alerts you to the fact that while you can’t immediately have what you want, you can sign up to be notified when the item becomes available again. Which places you on Taft’s marketing list. Now, you are likely to buy the shoes the moment you get the email saying they are available… because you were already interested, and you’ve seen them sell out before, which means if you do get the opportunity now, you’re going to jump on it!

But how do we apply this sometimes-gimmicky marketing tactic to a financial planning business?

Creating Scarcity By Simply Reorganizing Your Calendar With Surge Meetings

You may have read articles by Matthew Jarvis, Taylor Schulte, or Stephanie Bogan that highlight the efficiencies of running a client service model using the “meeting surges” approach. Yet while meeting surges is not a new concept, I have yet to see anyone use this approach with business development as a strategy to bring in more clients within a financial planning firm, instead of applying it only to servicing existing clients. Further, I have yet to see meeting surges of either type (i.e., surges that focus on client service or on business development) applied in a bigger firm, where advisors and their team members seem to be buried in carrying out the rote tasks and routines that feel more like ‘factory work’ and less able to dedicate more time to the ‘focus work’ needed for implementing new systems to better service clients and cultivate prospects.

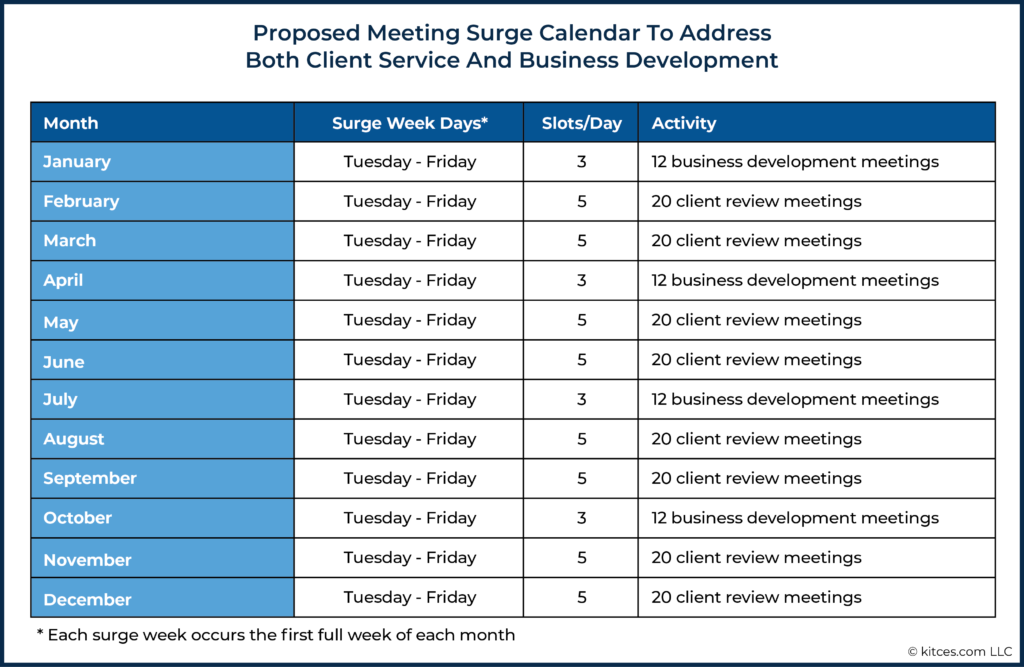

The basic idea of the surge meeting approach is that you handle all of your client reviews in a very condensed period, which you will find, is much more scalable. If done effectively with a homogenous client base, every market summary is the same, the same tax boxes are checked, and you, the advisor, are in a groove. However, this model is for existing clients. A modified surge model, such as the one illustrated below, can be applied to servicing clients and prospects.

With this strategy, advisors designate each month of the year as either a period to focus on business development or client reviews. Each month devotes a set number of slots to conduct meetings during the ‘surge week’ (e.g., 3 daily slots during the surge week in business development months, and 5 daily slots during the surge week in client review months). Surge weeks happen Tuesday through Friday during the first full week of each month.

As is the point with surge models, the remainder of the month consists of weeks of ‘non-surge’ work, which are left open to conduct other tasks to address the firm’s priorities (or simply being more flexible to allow team members to take extra time off).

You get the theme. Let me explain why this model can make sense.

First of all, the client surge model offers a number of potential benefits, including increasing advisor productivity and enhancing client experience. When client review meetings are structured in surges, the firm can better systematize and execute a repeatable review process, which reduces the total for reviews (especially when considering meeting prep time), while producing a more consistently high-quality review meeting experience for the end client.

Following this approach will allow 160 review meetings with existing clients per year, which can serve a client base of about 100 (as some clients will simply need to meet more frequently than once per year). And if you fill your first week of 12 prospect meetings with a 40% close rate, you will bring on about five new clients per quarter, or 20 per year. With the same initial client base of 100, this would equate to an approximate growth rate of 20% per year, while servicing all clients… primarily in one intensive week per month of client meetings (with 3 subsequent weeks of relative flexibility!).

Of course, this sounds great, but how might scarcity be used to book those 12 business development meetings more effectively in the first place?

Let’s start with your firm’s website. Your website is for your prospects. You are for your clients. In other words, the way prospects communicate with and evaluate your firm, at least initially, is through your website. The way clients communicate with and evaluate you is through you.

Accordingly, your website needs to clearly state when you accept new clients. For example, with the schedule illustrated in the graphic above, the messaging would be, “We prioritize our clients and our team members above all else. Accordingly, we only take meetings with prospective new clients one month per quarter, in January, April, July, and October. Thank you for understanding.”

How Scarcity Can Be Used To Market A Firm’s Value

By marketing the scarcity of time you can commit to prospect meetings, prospects will get a clear sense of the value that you place on servicing clients with your full attention. The difference with the above approach using surge meetings, compared to asking prospects to make an appointment at their convenience, is that you are instead offering a limited window of opportunity when appointment slots as a prospective new client are available each quarter.

By setting aside specific months of the year (and weeks of that month) when you open the door to prospects, you also establish a time frame in which the door will close. Too often we waste our time, thus reducing the time we could have otherwise spent with clients, by chasing procrastinators who will never commit.

Using a scarcity approach allows clients who aren’t ready to commit to self-select out because they won’t be comfortable making a decision by the 31st. Which means that those who are ready to take action will feel motivated to do so in the available window (while they can!), and those not ready to take action will opt out of wasting your time in a meeting that isn’t going to lead anywhere… a win-win in both scenarios!

When I moved to the Washington area in 2011, we shared Regus office space with a family office team that had just broken away from Merrill Lynch. On the welcome page of their website, they stated that in order to protect their high-touch service model, they had made a commitment to their clients to take on only one new family per quarter. Bold. But think about the impact this has on your client’s perception of the quality of your practice.

Furthermore, think about the conversations your clients have with their network around referrals. “Yeah, I really like what Evan and his team have done to help us with our financial goals; you should talk to them. But they take only one new family per quarter, so you should reach out soon.” The waitlist was the first example of scarcity I saw in high-end financial planning practices. While I view this as a simple change for a robust practice, it’s tough to apply to a business with significant growth goals. I believe the surge approach is more applicable in this situation.

The Drive For Consistency Can Support Clients’ Commitments To Goals

Fast forward to a few months after our home purchase last year. It’s December 2020, and I am now looking back on the election. We moved into our home in the summer, in the thick of election campaigns, and as soon as we were settled, we put our presidential candidate’s sign on the front lawn (I won’t say which one), ready to vote.

The point here is that once you make that front-yard statement, there is no way you’re not going to vote! If the world were split into two groups, political and apolitical, we had just committed to the political category. And there’s no going back on it once you’ve said it with a big sign on your front lawn!

Cialdini walks through several examples of how we have an increased likelihood of following through with commitments or goals once they have been made publicly. Part of his reasoning is based on the idea of consistency – we tend to have an inherent desire to align our behavior with the image we have painted of ourselves. Once we have made a choice about who we are and how we want to show up to others, we tend to make decisions consistent with that persona.

In the above example, putting a lawn sign in our front yard made me and my family view ourselves as ‘political’. And, in order to stay consistent with that political persona, we were more inclined to vote. Therefore, if we want people to vote, it’s important to have them commit (publicly, if possible) to this goal. Putting a sign on their front lawn is a great way to do this.

And yes, I have seen plenty of the back-and-forth discussion around goals-based planning and its lack of value because people don’t know what goals to set. I’ll get back to this later.

Clients Want To Behave Consistently With How They Identify Themselves

This is one of my opening statements that I use when presenting live educational seminars:

“One thing I love about teaching educational seminars is that the people who attend are doers. Let me explain what I mean. In the retirement landscape, there are drifters and doers. Drifters let their money lead their life. Doers let their life lead their money. The fact that you drove across town, despite having to sit in traffic, to learn about taxes in a library conference room, proves that you are a doer.”

When I open the seminar this way, I am clearly dividing the world of retirees into drifters and doers, and at the same time, I have made everyone in the room aware that they are doers.

According to Cialdini’s principle of consistency, the seminar attendees – having been identified as doers instead of drifters – will now act in a manner consistent with doers. And this will help them overcome one of the biggest obstacles common to retirees adhering to a financial plan: procrastination. Why? Because doers don’t procrastinate.

At the end of the seminar, we give this clear direction: “The toughest thing about personal finance is asking personal questions about your finances in a public setting. For that reason, we are offering each of you 30 minutes of our time to answer any of your questions, without any strings attached. Let me be clear, if you are a drifter who somehow drifted into this class, this is not for you, but for all you doers, here are the next steps…”

How Goals-Based Planning Can Be Used To Bolster Commitment

One of the biggest criticisms of goals-based planning is that there is ample research showing that people don’t actually know what their goals are. So, if we don’t know where we want to go, how can we possibly come up with goals to get us there? I disagree.

We so often confuse goals with transitions. Retirement is a transition. The things you will do in retirement – travel, spend time with grandkids, volunteer – are the goals. In other words, retirement is just the bridge to the island. We may not know when or how we will cross that bridge, but we do know what we hope is on the island. If the client does not know that, it is important that you offer an exercise that will help them work through this. This is homework that will help identify goals, without actually calling them “goals.”

Whenever someone signs up for a first appointment with us, we assign homework asking about their goals in retirement. We are lucky if 30% of people fill it out, but we have near-100% client conversion of those who do. How? Because we know that if people write down their goals, they are now significantly more committed to achieving them.

We call our exercise the Lifestyle Map and, as the name implies, it is a qualitative exercise. It starts by asking people about the things that they don’t want in retirement: As you think about your retirement, what do you want to change? What are the risks you’d rather live without? For most people, those questions are fairly easy to answer. Once they state what they don’t want, we turn to what they do want. For this, we use a variation of George Kinder’s three questions, that essentially serve to help clients drill down their goals to the ones that are most crucially important to them.

In summary, advisors can use the desire for consistency to protect clients from procrastinating on the important things they need to do to stay on track with their financial plans. Additionally, advisors can encourage clients to identify their goals, which will bolster their commitment to design their personal ‘island’. Once they have done this, with or without us, they are more likely to do what it takes to drive across the bridge that will ultimately bring them to their island!

Creating Reciprocity Through Free Planning Services Attracts Prospects And Increases Referrals

You know those dents, dings, and imperfections in your house that live at the very bottom of your to-do list? My wife and I had basically stopped noticing the dent in the drywall from moving our dresser in on day one. We didn’t pay any mind to the shoe molding that was coming off of the baseboard in the kitchen. This is the punch list of items that a good realtor will notice.

The day after we decided that we would at least test the market with our now ‘old’ home, Maria sent her contractor to repair all of these minor imperfections. We had not signed the Sotheby’s contract. There was no mention of how much the repair work would cost. Maria was simply acting as if we were already clients. She was letting us test-drive the client experience. And, in the process, she was creating reciprocity. By devoting time and energy into helping us with the decision to sell our house, there was no way, at that point, we wouldn’t sign the paperwork.

Cialdini has ample examples to support a world that revolves around reciprocity, in which strong relationships are built on a balance of deposits and withdrawals. This may be the most obvious influence that appears daily in our lives. When someone holds the door for you and you walk past, it would be considered socially criminal not to hold the next door for them.

This principle of reciprocity can be applied easily in our business by investing in our prospects, not just because it will help them, but because the advisor is making a ‘deposit’ in the relationship that the client will want to return (if they are indeed one worth working with!).

I have a speaking coach who often says, “People will hire you to solve big problems – if you can quickly show them how to solve small ones.”

So how can financial advisors create reciprocity in their sales process? Here are some ideas.

Free Planning For AUM Firms

I figured I’d tackle the most controversial issue first. I started in this industry at age 22 and went through a two-year training program. Subsequently, I taught that same program for three years. At that firm, we literally could not start a financial plan without submitting a financial planning contract and the associated check from the client for that plan. I was taught that, if you charge $0, the value of that plan is $0.

When I moved over to my current RIA, charging for planning was at the discretion of the advisor. Typically, we subjectively charged planning fees to people who we thought were more inclined to implement our advice themselves, instead of retaining our firm to help them with their ongoing planning needs. We were trying to protect our time. It wasn’t until 2018 when a consultant told us that with our rapid firm growth, both from a client count and team member standpoint, this flexibility was unsustainable. She said, “Charge or don’t charge, but it has to be consistent.” We decided to take the latter route, and it had nothing to do with the reciprocity principle I am discussing today. It was math.

We brought in about 75 new clients in 2020, but we built about 150 plans for prospective clients. By not charging, and assuming everyone who received a plan would be willing to fork over $1,500 for the plan (below market, I know), we had given up an estimated $225,000 in revenue.

However, we know that not everyone would have paid for a plan. So, let’s say that if 75% of the 150 who received a plan would have been willing to pay upfront, we would have given up $1,500 (price per plan received upfront) × 150 (prospective clients) × 75% = $168,750. This is less than the average revenue of 15 new clients paying AUM. We were simply making the bet that we would get at least 15 more clients by not charging, thereby removing a barrier to entry.

Cialdini would argue that the value of free plans goes even further. He would argue that if we hold the door open by building plans that actually help clients, we have created reciprocity—and because people don’t like being indebted, they are more likely to become clients. I hate to break it to you, but the vendors at a farmer’s market don’t just want you to taste how delicious their peaches are to appreciate that peaches are a delicious fruit. In fact, Cialdini cites several studies that say we will often resolve our initial debt with much bigger purchases. So, we buy a dozen peaches after trying 1/8th of one.

But here’s the catch: The peaches have to be good! Free planning allows each prospect to experience a really good peach. When a client writes a big check for a financial plan, we often feel an obligation to deliver a huge packet that encompasses every domain of the CFP curriculum. However, when we stopped charging, we also stopped giving out paper plans, which has allowed us to focus our time and energy on the things that are most important and urgent at that moment.

In other words, you don’t have to give away an entire plan to get a planning engagement. The farmer doesn’t give away an entire peach to sell a peach. He gives away 1/8th of a peach to entice a few people to recognize how delicious they are and feel inclined to buy a dozen in return. Accordingly, our goal is to provide solutions to those most urgent and solvable problems first. Our service model is set up to plug all of the other holes in the rest of the financial plan – if and when they become clients. We had fewer than five prospects request a full paper financial plan in 2020.

Think about it this way: If you had a contractor coming to work on your floors, and he pointed out that you needed new windows, you’d probably still want him to fix the floors first. Once again, if you can help them solve small problems, they will pay you to help them solve big ones.

Every Prospect Is A Client

In 2014, I was looking to buy a new car. Thanks to the overwhelming amount of information available at my fingertips, I already knew the model of Jeep I wanted. I had a client who was a partner at a local Jeep dealership, so I asked for his thoughts. His response: “Come by tomorrow. I’ll lend you one for a week. See if you actually like the thing.” This was the ultimate peach sample! I drove the car for the week. And then bought the exact same model, with just a different trim.

Even if I hadn’t liked the car I was driving, I’ll bet I would have bought another one off of his lot, because I felt indebted to him for lending me the car for such a long period. Reciprocity at work! But how do we apply it to an intangible product? Let your prospects test drive the experience.

Last week, a woman named Kathy came in for a meeting two years after an initial call. Since we always dictate notes for all of our meetings, I was able to pick up where we left off. In our initial conversation, I could see that her previous advisor had overlooked the fact that Kathy had the ability to claim a Restricted Application on her ex-spouse’s Social Security (which at the time hadn’t quite been fully phased out yet). And while Kathy didn’t become a client at the time of the initial call when we made that Restricted Application recommendation, she has always associated us with the monthly paycheck she has been receiving through her ex-spouse’s Social Security ever since our call two years ago. Because of this, we stayed top of mind, and now she has come back and hired us to manage her portfolio as she is getting ready to retire and needs to live off of her investments.

David Sandler, an absolute legend in the sales world, has what he calls “49 timeless selling rules”. Rule number two is, “Don’t spill your candy in the lobby.” The basic premise is that if we give away too much information upfront, the clients aren’t as motivated to engage us. I think many financial advisors can benefit from this rule by using it to create just the right amount of reciprocity between themselves and their prospective clients. The least experienced among us don’t often obey this rule; they spill all “the candy” in the initial meeting in order to prove their knowledge. In contrast, many of the most experienced don’t want to give away anything until the prospect has signed on the dotted line (but fail to invoke the reciprocity rule at all by being unwilling to share any candy whatsoever!).

My feeling is that there is a happy medium. Start by solving a client’s problems once you have an adequate understanding of their situation. In the previous example, there is no way that I would have given any Social Security advice without a full understanding of Kathy’s benefit and marriage situation. I also would never knowingly withhold that information just because she hadn’t yet become a client.

The best way for advisors to let prospects test drive the client experience they offer is to make the planning or presentation meeting as similar to a review meeting as possible. The core focus should be on solving problems. Use the same software and the same analytics tools that you would use if they were a client instead of a prospect. When you get to this point in the sales process, do not withhold advice. Ultimately, prospects will hire you for your wisdom and your ability to solve their future problems. You should never be afraid of providing too much value (not information) upfront; solving their current problem isn’t going to be your future value anyway, it’s just an opportunity to demonstrate that you can provide such value on an ongoing basis as well.

If you follow these steps, every prospect should have a great experience. But guess what? Not everyone will hire you. The timing may not be right. Your offering may not be the right fit. You may not be the right advisor for them. But as long as the experience was great, reciprocity will still exist.

A few weeks back, we had a prospect, Joan, who had lost her husband two years prior. Her current financial planning firm held her hand through that process and made sure she landed on her feet financially. Objectively, there was more we could have offered on the planning front, but her loyalty was still to her old firm. As I always do when a prospect says that they have chosen not to engage us, I parted graciously, telling her the “door is always open” should she change her mind.

I also told her that I understood her decision and that even though it wasn’t the right time for her, I would “always make the time to help the people she cared about.” If you haven’t tried this, you’d be shocked at how successful this strategy can be for referrals. I believe reciprocity is key. And Joan does, too – she recently introduced us to her widows’ support group and arranged for us to teach a class in 2021! Even though she hadn’t even become a client herself!

Now that you all know more about my home purchase than my own family does, it’s important to look back on why we ever wanted to move, and why we would be happy with a mortgage payment 1.5 times more than our last one. It’s because we wanted more room for our growing family. It’s because we wanted a yard for our daughter to play in. It’s because we wanted to be able to host the weekly Sunday dinner for our extended family.

We must never forget why clients hire us. It’s because they want someone to help them reach their goals. It’s not because they’ve deemed our services are worth $10,000 or $20,000 per year; it’s because they consider their goals are worth spending that to achieve.

Why am I saying “because” so much? The last bit of advice here is why using that very word is so important. “Because” is the link between the advisor’s services and the client’s goals, and it should be used frequently during the onboarding process. The reason clients want higher returns, lower taxes, and more income is because it will help them reach their goals.

We know that prospective clients don’t often have the knowledge to easily and fairly evaluate financial advisors. By using Cialdini’s research, though, advisors can offer these potential clients a shortcut to help them through the decision-making process… because prospects will be better off with you than without you. And if you feel good about your product, Cialdini’s principles will help you provide the ‘because’ that links your services to helping your clients achieve their most important goals!

Wow a lot of great information and detail in this article. The concept of reciprocity from Cialdini is not used strategically enough in most businesses. If you can do some basic live planning that doesn’t rely on printing a big report, then you can build trust and show them they may have a problem all at in one initial session. For example, you show them that they might run out of money in retirement. Once you do that, then simply say “Is that what you were planning to do?” When they say No then simply ask “Would you like some help with this?” and now you have transitioned to showing solutions… You can do all of that live using the RetirementView software. Also it gets them to share all their assets because when they see the red then all of a sudden they remember those other accounts that they “forgot to tell you about”.

Very Good!! I already bought the book!