Executive Summary

For clients receiving Incentive Stock Options (ISOs) as part of their compensation, the potential for wealth creation can be significant – but so too is the risk of adverse tax consequences if not handled properly. While many employees focus on the upside possibilities, few understand in detail how ISOs function or the critical role that taxes play in shaping their real take-home value. Advisors are uniquely positioned to help clients navigate these complexities, especially since poor planning around ISO exercises can create a substantial tax liability without generating the liquidity to pay it, thereby jeopardizing other aspects of the financial plan.

In this guest post, Daniel Zajac, Managing Partner of the Zajac Group, explores how ISOs work, the unique tax challenges they present, and the strategies advisors can use to help clients maximize their benefits. ISOs are attractive because, under the right conditions, gains from their exercise and sale can qualify for long-term capital gains treatment. However, to receive this preferential tax treatment, employees must wait to sell the employer stock until at least one year after exercise and two years after the original grant date. Failing to meet these thresholds results in a 'disqualified' disposition, where some or all gains are taxed as ordinary income.

The bigger complication with ISOs lies in their interaction with the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT). Exercising ISOs and holding the shares beyond the end of the tax year can trigger AMT liability on the 'bargain element' (i.e., the spread between the exercise price and the fair market value at exercise). This can leave clients facing large tax bills on paper gains from unsold stock without the liquid funds available to pay.

Several strategies can help mitigate the impact of AMT on ISO exercise. One approach is to exercise early in the calendar year, giving clients time to hold shares for the one-year requirement and still sell before the next year's tax deadline, using the proceeds to pay the AMT bill. Alternatively, clients may intentionally disqualify ISO-purchased shares by selling them before year-end, helping to avoid AMT altogether. While this subjects the gain to ordinary income tax instead of capital gains treatment, it eliminates the risk of phantom income and reduces concentration risk in the client's portfolio.

For clients intent on holding their shares long-term, advisors can help identify the "AMT crossover point" – the amount of ISOs that can be exercised without triggering AMT. This requires modeling the difference between regular tax and tentative minimum tax, which varies by income, deductions, and filing status. When AMT is paid, clients may be eligible for a future AMT credit, allowing them to recoup part of the tax over time when regular tax again exceeds AMT liability. While recovery is often gradual, advisors can sometimes accelerate it leveraging high AMT basis or timing qualified dispositions that widen the gap between regular and AMT capital gains.

Ultimately, ISOs offer a powerful planning opportunity but require careful coordination of tax efficiency, portfolio risk, and liquidity. AMT is not simply a hurdle to avoid but a tax timing issue that can be anticipated and managed. With proactive guidance, financial advisors can help clients use ISOs as a strategic tool – not just a compensation perk – to support long-term wealth-building and thoughtful, holistic financial planning goals!

When an employee, particularly a high-earning executive or company leader, is offered stock options as part of their compensation package, this creates what often feels like both a blessing and a curse. Stories about original Google employees amassing millions after the early 2000s IPO illustrate how equity compensation can serve as a fast track to building significant wealth in a relatively short period. For those who have the opportunity to benefit from stock options, a real opportunity exists.

But stock options, namely Incentive Stock Options (ISOs), are complicated. Many employees know little about how they work or what sort of planning and decision-making is necessary beyond the paperwork provided by their employer. This creates an important opportunity for advisors to guide clients through the benefits and potential challenges of ISOs.

Understanding ISOs is essential because they can greatly affect a client's wealth and tax bill, particularly when the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) comes into play. One of the main challenges is that ISOs can trigger AMT when exercised and held, often creating a significant tax liability without generating the cash needed to pay it. That mismatch introduces liquidity risk and can jeopardize a successful financial plan with a costly misstep. For advisors, a central task is helping clients anticipate when AMT is likely to apply and guiding the timing of exercises and sales in a way that balances tax exposure, cash flow, and single stock concentration.

What Happens When Your Client Is Awarded Stock Options?

Before looking at the tax consequences of exercising stock options, it helps to start with the basics of how they're awarded. To start, the employee is provided with an option grant, which is a document specifying critical information about the award, including:

- Number of shares the employee is eligible to purchase;

- Vesting schedule (outlining when the options can be exercised);

- Expiration date (the last day the employee can exercise the option); and

- Exercise price (commonly based on the stock price on the day of the grant).

The exercise price determines how much an employee pays to exercise each option. Multiplying the exercise price by the number of granted options indicates the total cost to exercise all shares.

The grant alone, however, doesn't reveal the true economic value of the award. That depends on the difference between the exercise price and the Fair Market Value (FMV) at the time of exercise – known as the intrinsic value of the option.

Example 1: Jane, an employee of Company A, is awarded a grant with a four-year vesting period. The grant gives Jane the option to purchase 1,000 shares at an exercise price of $10 per share.

Four years later, when the vesting period is complete, the market value of Company A stock has risen to $50 per share.

Because Jane's exercise price was set at $10 per share, her total cost is 1,000 × $10 = $10,000. Which means the intrinsic value of her options is $50,000 (FMV) – $10,000 = $40,000.

Once the options are exercised, employees can:

- Sell all shares immediately;

- Hold the shares for a future sale; or

- Use a combination approach, selling some shares and holding the rest.

Understanding the grant document and the potential intrinsic value is the foundation for any planning strategy. The next step is to consider how different types of stock options are taxed, since the tax treatment ultimately drives much of the planning around when to exercise and sell.

How Stock Options Are Taxed

The tax liability on stock options can be complex and depends on the type opf option and specific circumstances of the transaction. Broadly, there are two types of stock options:

- Non-Qualified Stock Options (NQSOs)

- Incentive Stock Options (ISOs)

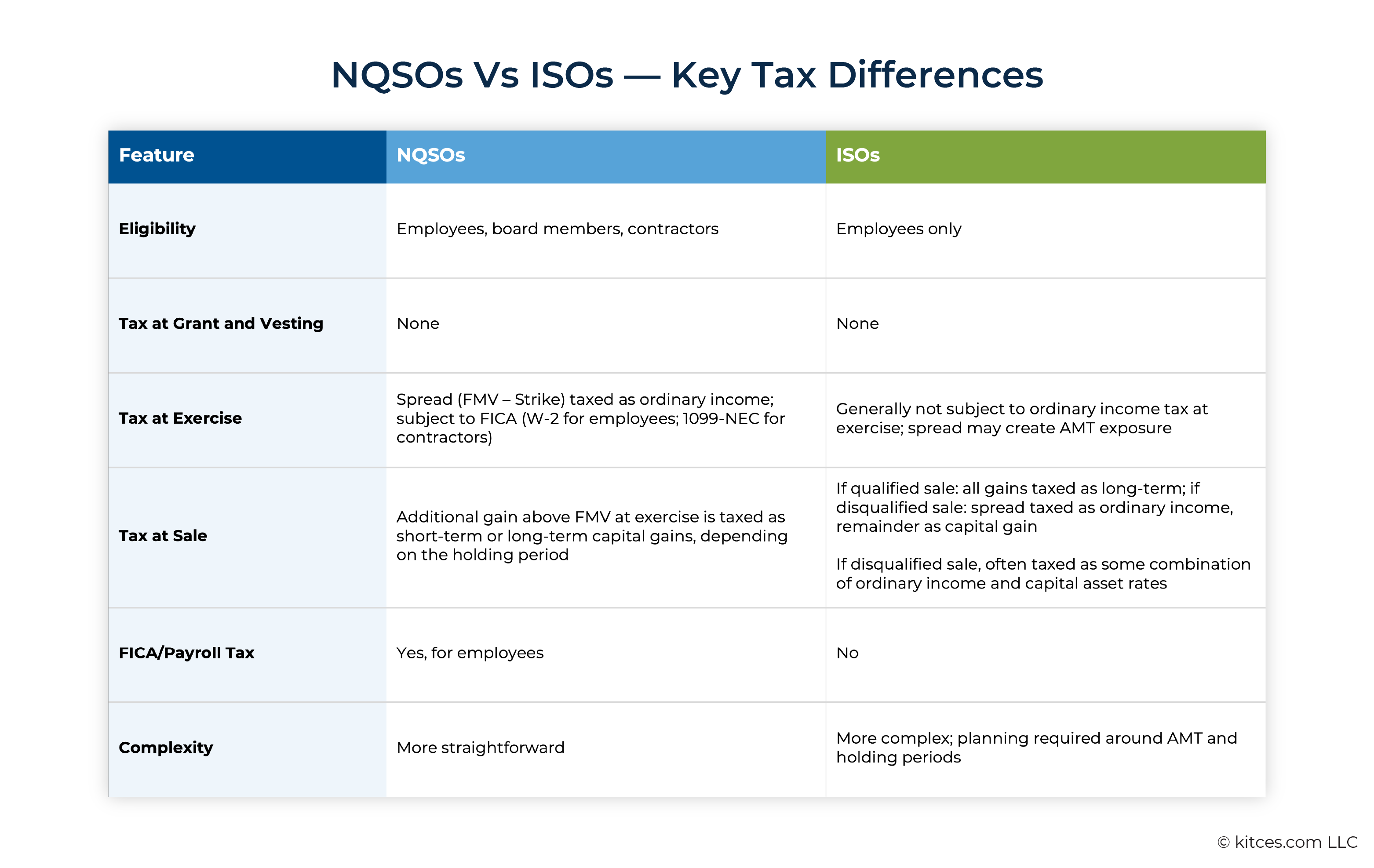

Both types share the same general mechanics: the employee is given an exercise price at grant, the options are subject to a vesting schedule, and once exercised, they may be subject to tax. Where things start to differ is in how those taxes apply.

NQSOs are the more straightforward of the two. As an employee, the spread between the FMV and exercise price is taxed as ordinary income at exercise, subject to payroll tax, as well as state and local tax. If the shares are later sold for a profit above the FMV at exercise, the additional gain is taxed as either short-term or long-term capital gains depending on the holding period.

NQSOs also have fewer eligibility requirements than ISOs, making them more widely available to both employees and certain non-employees as well, including board members and contractors.

ISOs, on the other hand, are available only to employees, and their tax treatment gets complicated (though, in the end, they may offer some tax advantages over NQSOs). Like NQSOs, they are not taxed when granted or when they vest. Unlike NQSOs, ISOs are not subject to ordinary income tax upon exercise. However, if the shares are sold before meeting the holding period requirements, the spread may be treated as ordinary income. Additionally, exercising ISOs and holding the shares can trigger exposure to AMT on the bargain element (the difference between the exercise price and FMV at exercise).

Qualified Vs Disqualified Sale

Exercising stock options is only one step in the process. The tax treatment of the eventual sale – whether it involves ordinary income, capital gains, or AMT – depends on how long the shares are held, which determines whether the disposition is classified as a qualified or disqualified sale under IRS rules.

In general, there are two criteria for a qualified sale:

- The sale occurs at least two years after the option grant date; and

- The sale occurs at least one year after the exercise date.

If both conditions are met, the entire profit – from the exercise price of the stock to the final sale price – is taxed as long-term capital gain, which is generally more favorable, as the top rate is 20%. If the sale does not meet these criteria, it is considered a disqualified sale, meaning some or all of the profit may be taxed as ordinary income.

The table below summarizes the key eligibility and tax differences between NQSOs and ISOs.

A Brief Reintroduction To AMT

While both NQSOs and ISOs have unique tax considerations, AMT comes into play only with ISOs. NQSOs are taxed as ordinary income at exercise, similar to cash compensation, and have no direct impact on AMT. ISOs, by contrast, can trigger AMT when exercised and held. Because of this, ISOs present a more complex planning challenge – and understanding their interaction with AMT is critical for advisors when guiding clients through equity compensation decisions.

As noted earlier, ISOs are not taxed at exercise. However, exercising ISOs and holding the shares can create exposure to AMT. Which means employees – often including higher earners who may not have previously encountered AMT before – are more likely to face it in the year they exercise and hold their options.

AMT can complicate the decision of whether to exercise and hold or to exercise and sell. The key to making informed decisions lies in understanding how AMT liability is calculated, since that framework drives the planning strategies that follow.

Determining AMT Liability With Tentative Minimum Tax

Just as it sounds, AMT is an alternative tax system. It requires taxpayers to calculate liability twice – once under the regular tax system and once under the AMT system – and then pay whichever amount is higher. It applies primarily to individuals above certain income thresholds or those who engage in certain activities – such as exercising and holding ISOs.

Liability is determined using IRS Form 6251, which calculates Tentative Minimum Tax (TMT). If the taxpayer's TMT is higher than their regular tax, the difference is owed as AMT.

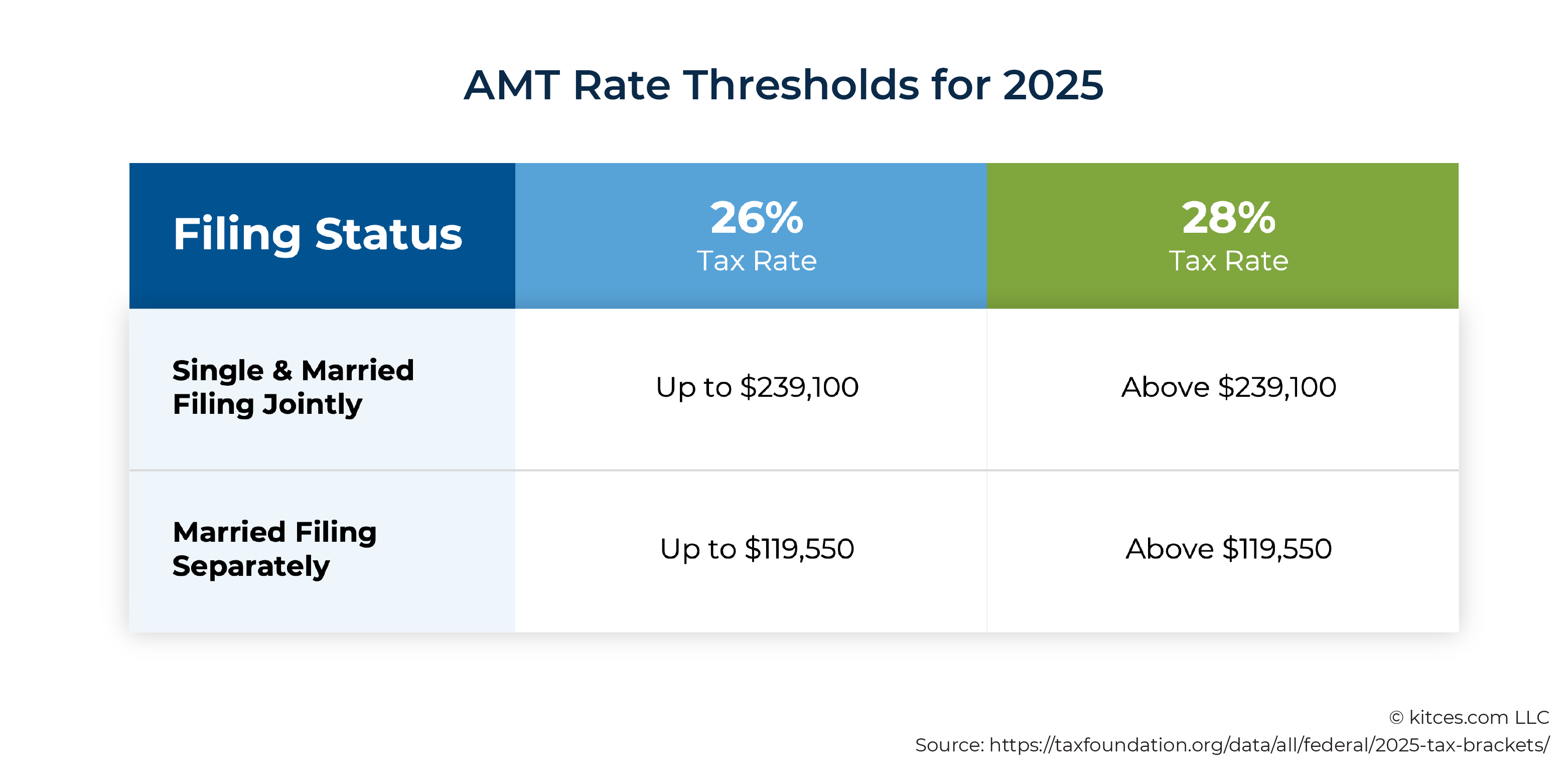

The AMT rate is either 26% or 28%, depending on the individual's Alternative Minimum Taxable Income (AMTI). AMTI starts with regular taxable income but is adjusted to include for certain tax 'preference items' that are treated differently under the AMT system – such as the bargain element from exercising and holding ISOs.

If AMTI is below the 26%/28% dividing line, your client will be taxed at a flat 26% rate. If AMTI is over the dividing line, then the portion of income below the dividing line is taxed at 26%, and the remainder is taxed at 28%.

Similar to the regular tax system, certain deductions and exemption levels apply based on filing status and the amount of AMTI. For 2025, the exemption levels are $88,100 for single filers and $137,000 for joint filers. For higher-income taxpayers, part of their exemption phases out – reduced by 25 cents for every dollar above the threshold. In 2025, the phaseout begins at $626,350 for single filers and $1,252,700 for married filing jointly. Understanding how TMT is calculated and how AMTI flows into that process is the foundation for seeing why exercising ISOs so often leads to AMT exposure.

Why Exercising ISOs Triggers AMT – And How AMT Credits Can Help

When ISOs are exercised and held in pursuit of a qualified disposition, the tax return requires an adjustment for the bargain element (the difference between the exercise price and the FMV at exercise). Because the bargain element is included only for AMT calculations – not for regular tax – it often increases Tentative Minimum Tax (TMT) enough to trigger AMT liability.

While this added liability can be significant, the good news is that it's often temporary. The tax paid as AMT in one year may be returned in later years as an AMT credit. In practice, AMT often functions as a 'prepayment' of tax that would otherwise be due at the time of a qualified ISO sale.

The AMT credit represents the portion of AMT paid in excess of regular tax in the year of exercise. In later years, when regular tax exceeds TMT, the difference between the two becomes the amount of AMT credit that can be used to reduce the tax bill. Because the credit can only be applied to the extent regular tax is higher than TMT, recovery is often gradual and may stretch across several years.

Example 2: Suppose Bob is a married taxpayer who files jointly with his spouse and who paid $50,000 of AMT last year after exercising and holding ISOs.

When projecting his upcoming tax return, his advisor finds that Bob's regular tax is expected to be $51,000, while his TMT is $43,000. Because regular tax is higher, Bob will be required to pay $51,000.

However, because he paid $50,000 in AMT last year, he is eligible to apply a credit equal to the difference between his regular tax and TMT toward his upcoming tax bill, reducing his total tax due.

This means that Bob can apply $51,000 (regular tax) – $43,000 (TMT) = $8,000 in AMT credit. Which means that his tax bill drops to $51,000 – $8,000 = $43,000.

This leaves $50,000 (last year's AMT payment) – $8,000 (AMT credit used) = $42,000 in potential AMT credit carryforward, which Bob can use in future tax years – for as long as he and/or his spouse is alive.

Importantly, a qualified sale is not required to begin using AMT credit. Some credit may be returned in years when no ISO shares are sold, depending on the gap between regular tax and TMT. The amount of AMT credit recovered varies each year and is limited by the spread between regular income tax and TMT. Employees with lower incomes may see a smaller amounts returned across many years, while high-income earners are more likely to receive larger credits, even in years when no ISO shares are sold.

Strategies To Address AMT When Exercising And Holding ISOs

As discussed earlier, ISOs and AMT often go hand in hand, which makes can make planning around equity compensation more complicated. That being said, there are several strategies advisors can use to help clients anticipate and prepare for the tax impact of AMT.

Every decision regarding ISOs carries trade-offs – affecting not only taxes, but also risk exposure, liquidity, and long-term growth potential. AMT planning is important, but it's still only one factor among many, and it shouldn't overshadow broader portfolio and cash-flow considerations.

Strategy #1: Timing ISO Activity

The timing of ISO exercises can significantly influence AMT liability. Exercising and holding ISOs past the end of the calendar year requires the bargain element to be included as a tax preference item for figuring TMT for that year, which can create a significant AMT bill without any shares sold to create cash flow to pay it. Combined with the actual cost of exercising the shares, this strategy can introduce liquidity challenges for employees.

Example 3: An employee exercises ISOs in July 2025 and holds the shares beyond December 31, 2025.

The bargain element must be included when calculating TMT for the 2025 tax year, even though they haven't sold any shares.

Which means that, by April 2026, they could face a significant AMT tax bill.

Now the question is, how can timing choices reduce, mitigate, or manage a large AMT bill when exercising ISOs?

Exercising Early In The Calendar Year

Recall that in order for the profit from the sale of stock option shares to be taxed as capital gain, the sale must be “qualified”. In order to be considered a qualified sale, the sale must meet two conditions: 1) it takes place at least two years after the option grant date, and 2) it occurs at least one year after the exercise date.

By exercising ISOs early in the calendar year, taxpayers have the opportunity to satisfy the one-year holding requirement before the next year's tax deadline, when they can sell their shares as a qualified disposition. This allows them to capture long-term capital gains and pay their AMT bill from the proceeds!

For this strategy to work, the shares need to be sold before the next year's tax deadline.

Example 4: Kathy is granted ISOs on February 1, 2022. On March 1, 2025, she exercises her options, resulting in an AMT liability on her 2025 tax return, due in April 2026.

Kathy's financial advisor recommends that she hold her shares until March 1, 2026, which allows the sale to meet the criteria for a qualified disposition.

When Kathy sells her shares in March 2026, she uses the proceeds to help cover her AMT bill due in April.

Intentionally Disqualifying Late In The Calendar Year

Some employees may prefer to wait until late in the calendar year to exercise their options, when they have a clearer picture of their total taxable income and capital gains. Which can be helpful – since the ISO bargain element isn't the sole contributing factor in determining AMT liability, waiting until closer to the end of the year can allow for a more informed decision about whether, and how much, to exercise.

Late in the year is also a proper time to review clients' current year activity and consider a change of strategy, if applicable. Suppose a client exercised and held ISOs early in the year, but by December, the stock price has dropped. If they continue holding through year-end, they may end up paying AMT on 'phantom' income – that is, on the higher value of the stock at exercise, even though that value no longer exists. In a really unfortunate scenario with a severe market downturn, the client could end up paying more in AMT than the stock is worth.

To avoid this scenario, ISO rules allow the employee to sell the shares before year-end as a 'disqualified sale'. By intentionally disqualifying the sale, the bargain element is eliminated as an AMT preference item, and AMT liability for that year can be avoided. The trade-off is that the spread between the exercise price and final sale price is often taxed as ordinary income instead.

Strategy #2: Avoid AMT Altogether

There are some approaches that allow clients to avoid AMT liability altogether – though they may come with trade-offs.

Exercise And Sell

As discussed earlier, AMT exposure arises when ISOs are exercised and held. By contrast, if the employee exercises and immediately sells the shares, no AMT liability is incurred. Instead, the spread between the FMV and the exercise price is taxed as ordinary income, and the proceeds create immediate cash flow. Selling also reduces single-stock concentration risk that can come with holding a large amount of employer stock in a portfolio.

The drawback is that selling employer stock immediately after exercise eliminates any potential for future growth, and the opportunity to benefit from long-term capital gains treatment from a qualified sale is lost.

Leverage The AMT Crossover Point

Another way to limit exposure is to exercise ISOs only up to the AMT crossover point – the level where TMT equals regular tax. In other words, the crossover point represents how much of the bargain element an employee can generate before AMT liability begins.

The practical challenge is that the size of this 'headroom' varies by taxpayer. The narrower the spread between regular tax and the AMT crossover point, the smaller the amount of ISOs that can be exercised without triggering AMT. A wider spread allows for more ISOs to be exercised and held. Advisors therefore need to consider two key questions:

- How many ISOs can be exercised and held while still keeping regular tax higher than TMT?

- How much bargain element can be generated before reaching the AMT crossover point?

To illustrate how this can play out in practice, consider the following example:

Example 5: Katie and Christopher are a married couple who earned $300,000 in 2025 and claimed the MFJ standard deduction ($31,500). Their effective tax rate is 18.7%, bringing their total tax bill to $50,134.

Under the AMT system, their Alternative Minimum Taxable Income (AMTI) is $300,000, reduced by the $137,300 exemption for joint filers, leaving $162,700 subject to AMT. At a 26% tax rate, their Tentative Minimum Tax (TMT) is $42,302.

Since Katie and Christopher's regular tax bill of $50,134 exceeds the TMT of $42,302, no AMT liability is owed, and they will be required to pay $50,134 in taxes. The spread between the two tax calculations is $50,134 – $42,302 = $7,832, representing the headroom available to exercise ISOs before AMT applies.

Their crossover point is calculated as $7,832 (spread) ÷ 26% (AMT tax rate) = $30,123.

Using this simplified calculation, Katie and Christopher could exercise and hold $30,123 of the bargain element and still pay no AMT.

This type of crossover analysis highlights the value of careful modeling. While a simplified example can illustrate the concept, in practice, projecting the true crossover point requires detailed inputs and tax software to account for all variables in determining the true tax liability.

Strategy #3: Take Advantage Of AMT Credit

AMT credit provides a mechanism to recover some of the tax paid in the year of an ISO exercise and hold. However, credit recovery is rarely immediate. In some cases, it can take years before the full AMT credit is returned.

Generally, AMT is only paid in years when ISOs are exercised and held. A qualified sale is not required to begin using the credit – in practice, some AMT credit may be returned even in years when no ISOs are sold, as long as regular tax exceeds Tentative Minimum Tax (TMT). That said, a qualified sale can, in fact, lower TMT, which creates a greater spread and increases the amount of AMT credit returned in a single tax year.

Advisors can also review the AMT basis of previous ISO exercises, which can highlight where future credits may be recovered. The bigger the spread between the regular basis (or exercise price) and the AMT basis (the FMV at exercise), the greater the potential for a negative adjustment to the TMT.

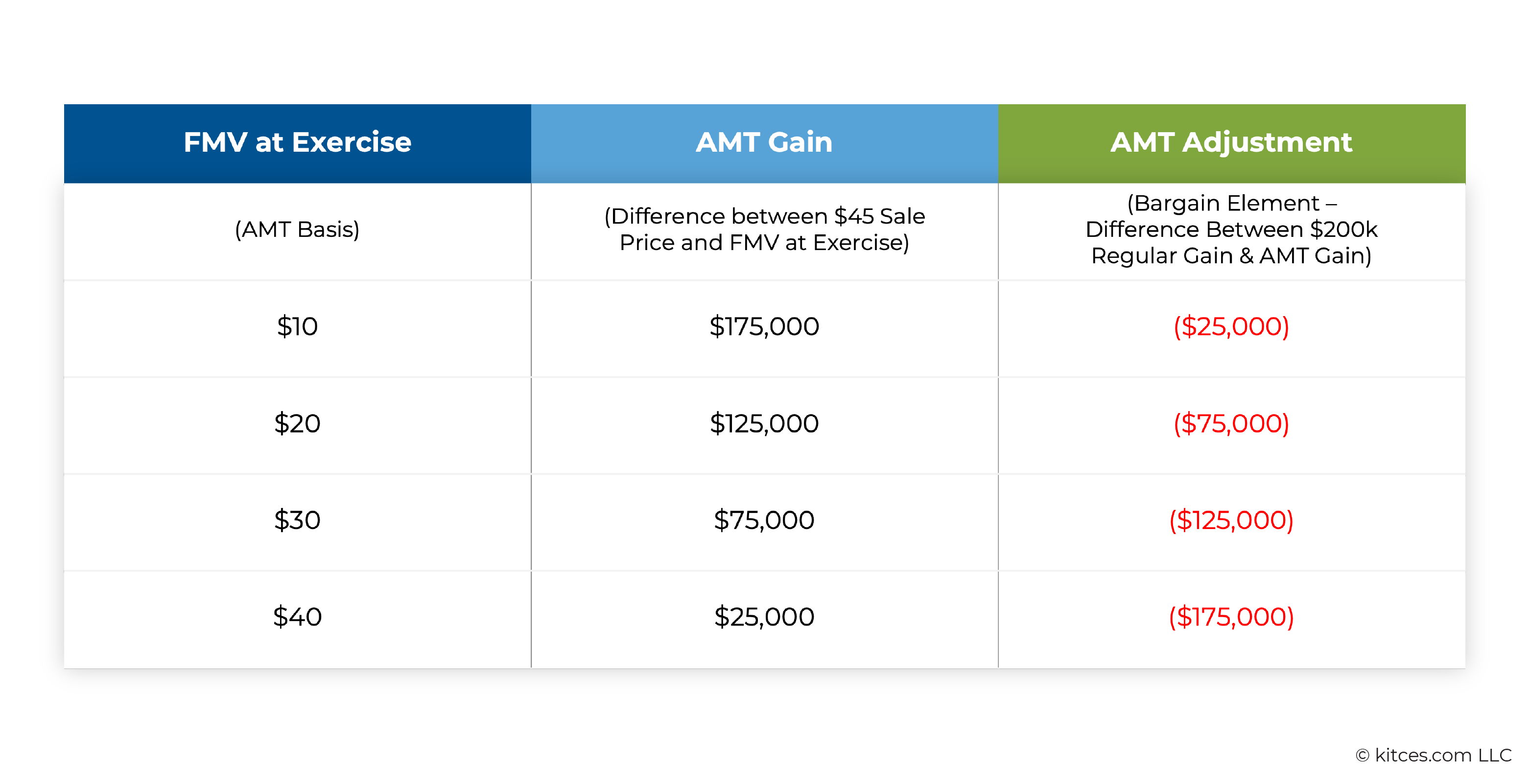

The following example illustrates how different FMVs at exercise can affect the size of the AMT adjustment – and, in turn, the potential for recovery of the AMT credit.

Example 6: Arlene was awarded 5,000 options with a $5 per share exercise price. The cost to exercise all shares would be $5 × 5,000 = $25,000, which is her tax basis under the regular system.

If she exercises when the FMV is $10, the bargain element is ($10 – $5) x 5,000 = $25,000. This amount is added to Arlene's income for AMT purposes, creating an AMT adjustment in the year of exercise. Under the regular tax system, though, the $25,000 is not recognized until the shares are sold.

When Arlene later sells all 5,000 of her shares at $45 per share, her regular gain is ($45 – $5) × 5,000 = $200,000, determined by the FMV at sale less Arlene's exercise price. By contrast, her AMT gain is ($45 – $10) × 5,000 = $175,000, based on the $10 FMV at exercise.

The table below compares different FMVs at exercise and shows how different AMT gains can result when Arlene sells her shares, depending on the FMV at exercise. Arlene's regular gain at sale is fixed at $200,000 (based on selling at $45), regardless of the FMV at exercise, but her AMT gain shrinks as the exercise FMV increases. That may widen the gap between regular tax and TMT. A larger difference may mean a higher AMT paid up front, but also the potential to accelerate AMT credit.

Notably, the final adjustment on Form 6251 for AMT credit is based on the difference between regular and AMT capital gain across the entire return, not just ISOs. Other capital gains and losses can affect the outcome as well.

If long-term carryforward credits are less appealing, clients may instead consider selling some ISOs immediately in a disqualified disposition. While this accelerates ordinary income tax, it also generates immediate cash flow, reduces the risk of a large AMT bill, and can lower the amount of AMT credit carried forward into future years.

ISOs can play a powerful role in building long-term wealth, but they also introduce complexity – particularly when AMT enters the picture. While AMT liability can feel intimidating for clients, it doesn't have to derail their financial plan. With careful planning, advisors can help clients decide when to exercise and hold (or sell) ISOs, when AMT is likely to apply, use timing strategies to balance liquidity and tax exposure, and leverage AMT credits in future years to recover taxes paid up front.

Ultimately, the challenge is less about avoiding AMT altogether and more about integrating it into the broader planning strategy. When approached proactively, ISOs can remain a valuable and sometimes pivotal component of a client's compensation and wealth-building journey.

Disclosure: Securities and advisory services offered through Commonwealth Financial Network®, Member FINRA/SIPC, a Registered Investment Adviser.

Whiteland Business Park - 740 Springdale Drive, Suite 204 - Exton, PA 19341 - (610) 719-0900

Leave a Reply