Executive Summary

For newer financial advisors, few situations feel more daunting than being asked a question in a client meeting that they can't confidently answer. In these high-pressure moments, the fear of appearing unprepared or inexperienced can be overwhelming – particularly when trying to earn the trust of both senior advisors and clients. Importantly, these moments of uncertainty are not only inevitable, they're also pivotal opportunities for professional growth. When handled skillfully, saying "I don't know" can actually enhance – not undermine – credibility, build trust, and reinforce the advisor's long-term value.

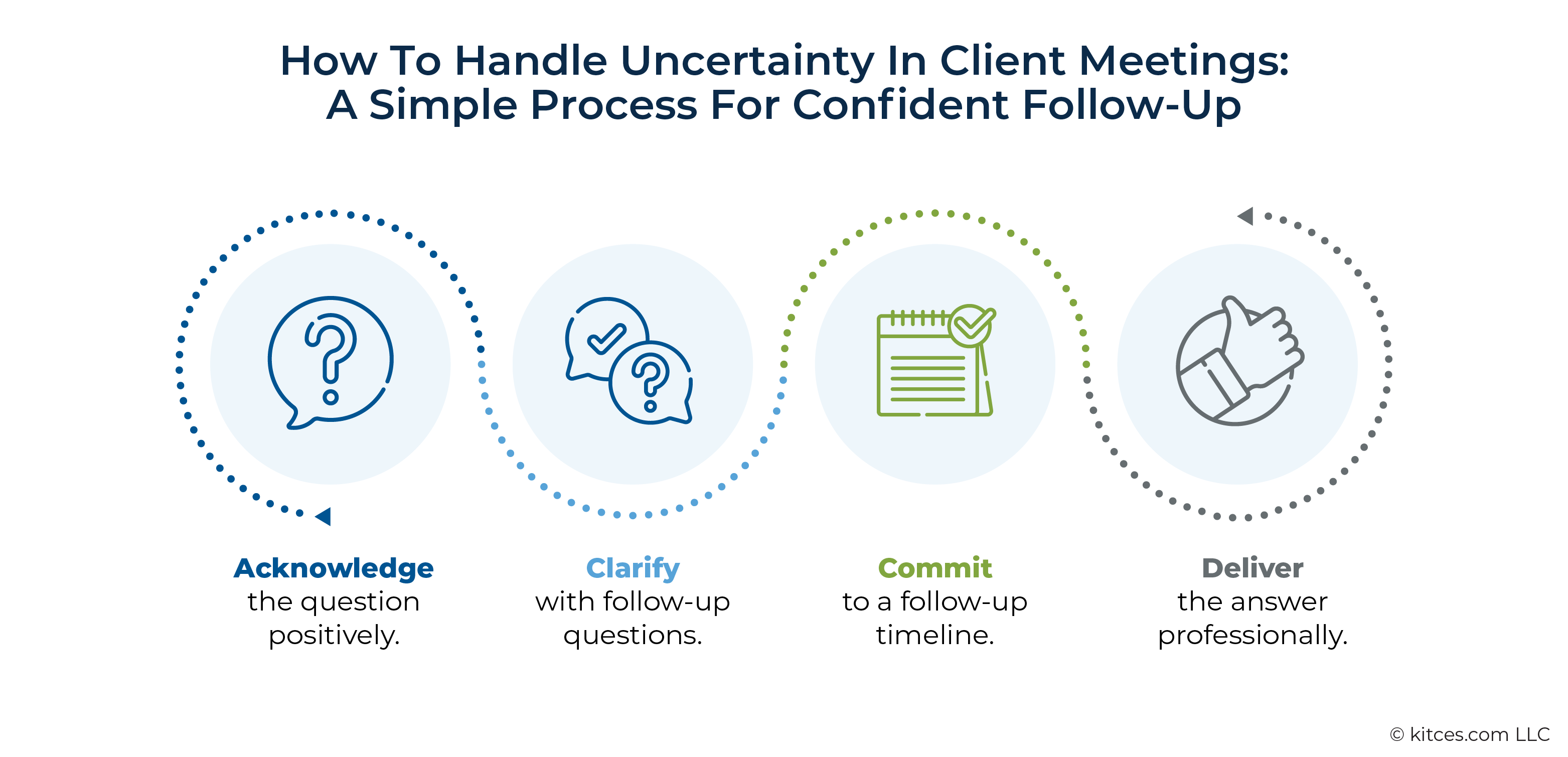

In this article, Sydney Squires, Senior Financial Planning Nerd, describes how early-career advisors can reframe their mindset around not knowing an answer on the spot and see moments of uncertainty not as threats, but as meaningful opportunities to build trust and demonstrate maturity. After all, even with a solid technical foundation, no one can recall every detail on demand. Advisors who are early in their careers may still be establishing credibility with clients, which can make even small stumbles feel momentous. However, what truly builds trust over time is how they navigate these moments, not whether they avoid them altogether. When a question arises that an advisor doesn't know the answer to, it helps to start by calmly acknowledging the question, asking a few additional questions to further examine the details of the client's scenario, and then committing to follow up within a reasonable timeframe. After the meeting, the advisor can follow through as promised by researching the answer and providing a thoughtful response.

Advisors can also spend time outside of calls honing their client meeting skills. For example, if clients frequently ask similar questions, advisors may want to adjust how they explain certain concepts, dive deeper into their own education, or create client-friendly resources. They may also ask for feedback, participate in mock meetings, and reflect on areas for improvement. At the same time, advisors who struggle with perfectionism or impostor syndrome may find themselves over-preparing for meetings or replaying every misstep afterward. In these scenarios, it may help to distinguish between self-perceived mistakes and actual points of feedback provided by supervisors or even clients. Over time, combining proactive preparation with regular practice can help advisors grow their confidence and effectiveness.

The ability to say "I don't know" with poise is a crucial skill for financial advisors. Clients rarely expect perfection; what they do expect is a thoughtful, honest advisor who will follow through with reliable guidance. By reframing these moments as opportunities, advisors can cultivate stronger relationships and deepen client trust over time. With the right mindset and communication tools, even the most uncomfortable questions become chances to demonstrate integrity, diligence, and genuine care – qualities that define a great advisor!

For many advisors – especially those early in their careers – there are few moments more stressful than being asked a question they don't know how to answer. And in the high-stakes situation of a client meeting, advisors may worry that not knowing threatens their credibility.

For example, consider this quick case study:

Rose started as an associate advisor at Winslet Financial two years ago and has been working hard to move upward. She has been shadowing client meetings and is starting to handle more client communication, from emails to presenting parts of the client meeting agenda.

During a discussion of estate planning strategies with two long-term clients, one of them follows up with a question about minimizing the tax consequences of a specific approach. Rose knows there's a strategy to reduce the tax impact, but the actual mechanics – and how to apply them to the clients' situation – completely escape her.

Dread builds within her. She becomes acutely aware of herself in the room. After working so hard to reach this point, she worries that if she admits, "I don't know for sure", she'll lose her hard-earned credibility with both the senior advisor and the clients. At the same time, she doesn't want to disrupt the meeting by pulling up a Nerd's Eye View article on her laptop to find the answer. Should she pass the question back to her manager? Should she simply say she doesn't know?

Moments like this are common. And while they can feel daunting, these situations are a normal part of growth that can help develop confidence and build trust over time. They don't have to derail a meeting or diminish trust!

Why Is It So Hard To Say "I Don't Know"?

In my work with advisors over the years, one struggle has come up consistently as they build their careers and develop their client meeting skills: saying "I don't know" or "I'm not sure" to clients. In the early days of an advisory career, new entrants are trying to put themselves out there to prove their capability – while also trying hard not to bungle those opportunities.

In client meetings, the stakes can feel high. Both senior advisors and clients – who are often older than the associate advisor – are watching closely. Newer advisors are working to build trust and credibility with senior advisors ("Trust me with your clients!") and with clients ("Trust me with your life savings!"). And opportunities to demonstrate that competence may be hard-earned.

Simply put, saying "I don't know" in a meeting rarely feels great, especially when it's a question the advisor feels they ought to be able to answer. At the same time, there's no avoiding it, even for advisors with a strong technical foundation.

Yet, the increasing sentiment amongst advisors, their managers, and clients alike is that technical knowledge is now considered ‘table stakes'. What often matters most in moving to the next level is client communication skills and emotional intelligence. In fact, managers of advisors who I've interviewed consistently expressed confidence in associate advisors' foundational technical skills – but emphasized that what they valued most were strong client-facing skills.

A core part of building those skills is learning to handle moments of uncertainty. Even with robust preparation, no one can remember everything or anticipate every question. Advisors who avoid situations where they might not know the answer often struggle to develop their client meeting skills. But those who embrace these situations – and learn to work through them – often end up excelling in the long term!

How Experience Correlates With Confidence And (Perceived) Competence

In speaking with advisors about how they developed the skills to navigate moments of uncertainty while keeping their poise, one sentiment that came up frequently: Telling clients "I don't' know" was hard at first but became easier over time.

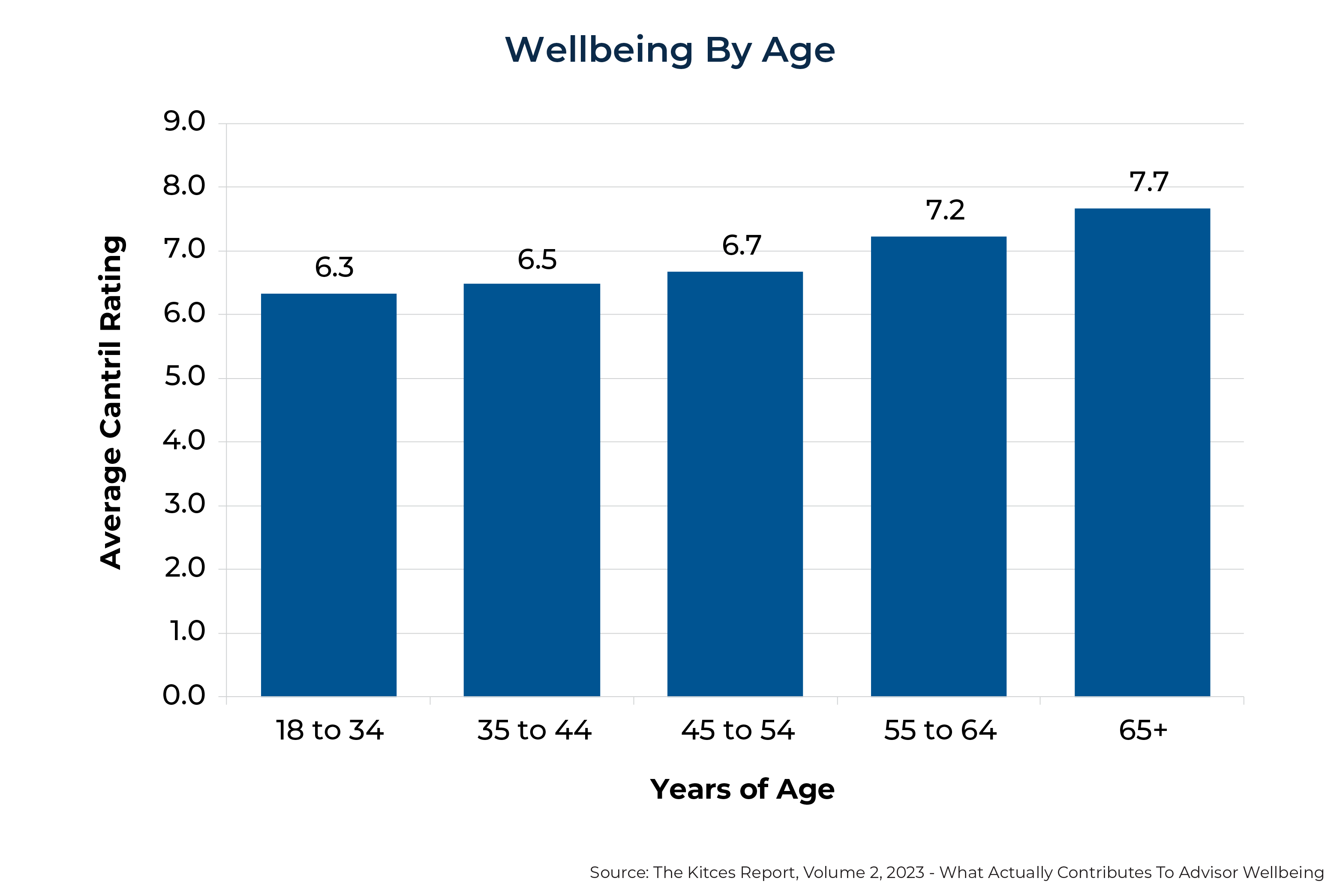

There's a lot of data to back this up. Kitces Research on What Actually Contributes To Advisor Wellbeing found clear correlations between self-reported wellbeing, age, and experience. Advisors aged 18–34 self-reported an average wellbeing score of 6.3 out of 10, which steadily increased across age groups. Advisors aged 65+ reported the highest satisfaction, averaging a 7.5 wellbeing score.

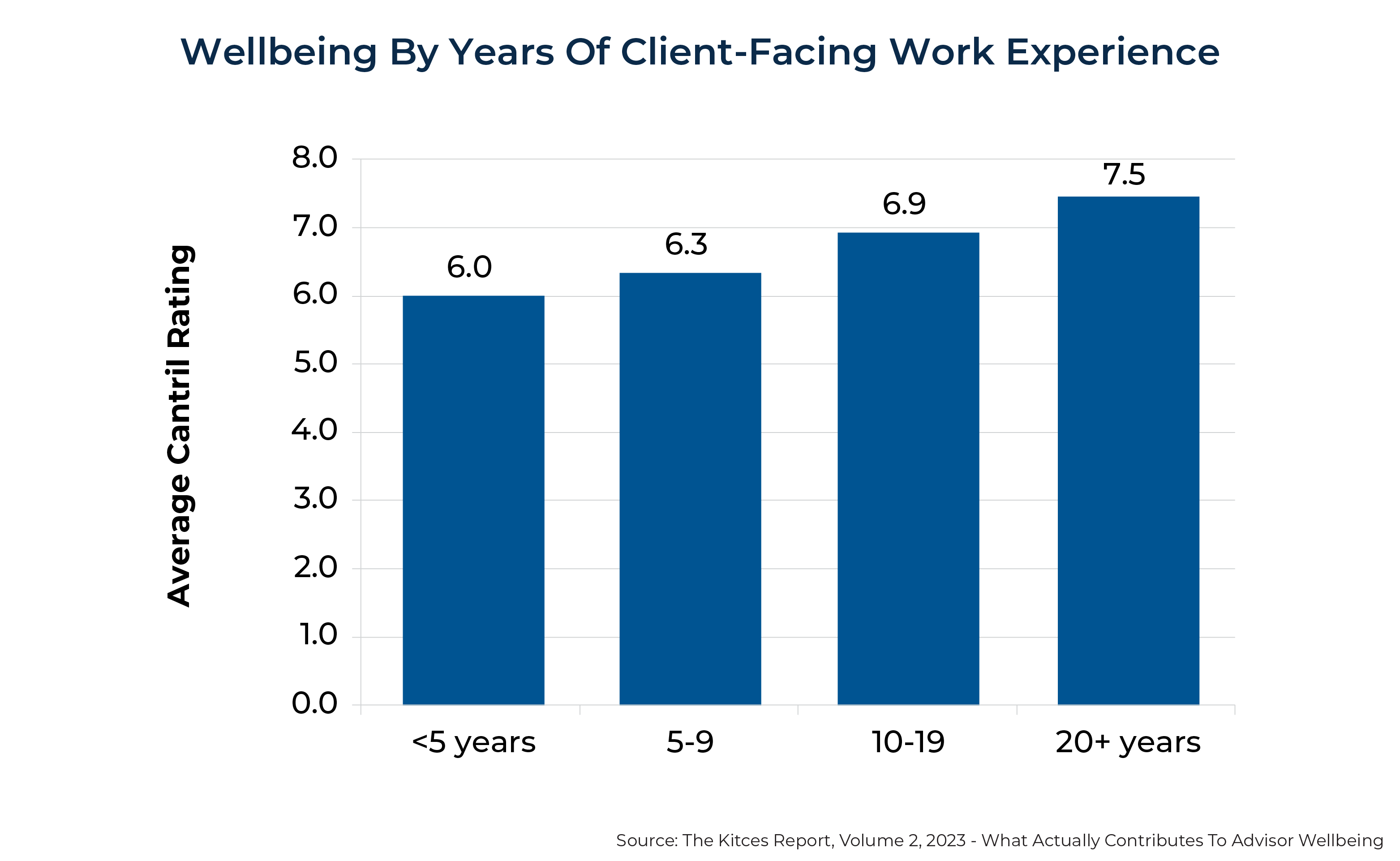

A similar pattern held for experience: Advisors with less than five years of client-facing work experience reported an average 5.9 wellbeing score, while advisors with 20+ years of experience averaged 7.5. In short, both age and experience support advisors' professional wellbeing.

Some of these findings can be attributed to the path that many advisors follow throughout their careers. Over time, they curate a role, firm, and client relationships that best suits their strengths and preferences. Confidence also grows holistically as advisors accumulate knowledge, build expertise, and gain social credibility, often supported by accumulating advanced titles and designations.

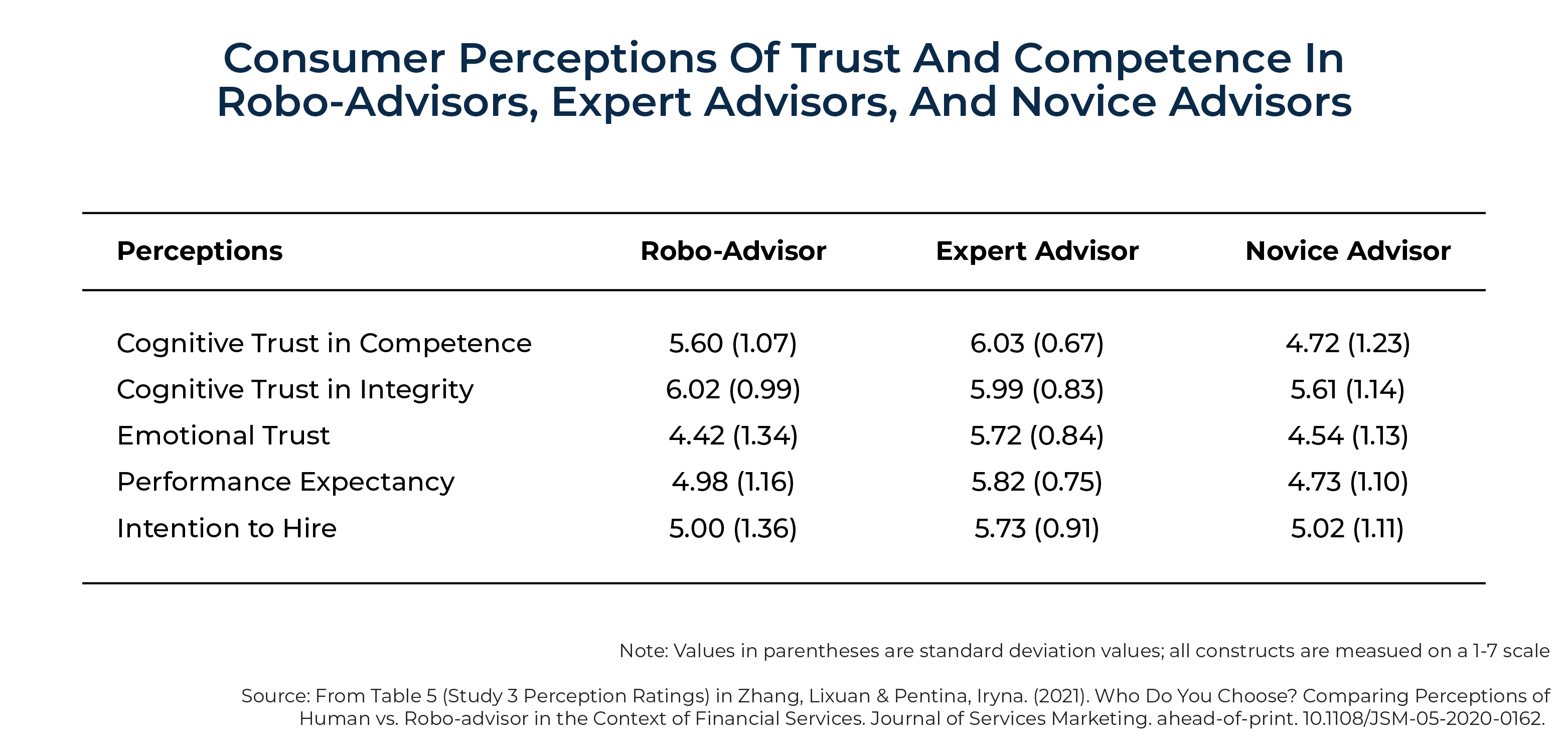

In the early years of a career, advisors are often working to establish both their technical expertise and their perceived credibility. This creates very real pressures to prove themselves. A 2021 research study published in the Journal of Services Marketing (Zhang, Pentina, and Fan) examined how consumers perceived trust in different types of advisors: experienced human advisors, novice human advisors, and robo-advisors. In the final round of surveys, researchers asked participants to rate emotional trust (reflected as integrity) and intellectual trust (reflected as competence).

Interestingly, consumers reported the highest trust in the integrity of robo-advisors, followed by experienced human advisors, and finally novice human advisors. For competence, experienced advisors led in scoring, then robo-advisors, with novice advisors again coming in last. Notably, novice advisors did outperform robo-advisors on emotional trust, and participants were almost equally willing to hire robo-advisors or novice advisors.

All of this can matter tremendously for younger or newer advisors when in meetings and calls. Comments about an advisor's age or experience – like being told they're the same age as the client's grandchildren, or even being flat-out asked why they should be entrusted with the client's money – can hover in the back of the advisor's mind long after they're spoken and reduce their confidence over time. Even when the advisor has strong technical skills, these comments can turn into doubts that resurface whenever a question arises that they can't immediately answer. (As a young director, I remember thinking that I couldn't wait until I had turned a respectable age, like 25, to run a department so that I would stop getting comments about my age. The comments did not stop at 25.) Given that these studies show experienced advisors are both more satisfied and more trusted, it can feel like the only solution is to build a time machine, or develop some technology that allows experienced advisors to simply grow out of the ground. but, in the meantime, the only way to become an experienced advisor is to be a novice for a while first.

In the context of not knowing answers in meetings, it may be helpful to recognize that some of the skepticism and pressure to demonstrate credibility will get easier over time as an advisor gains experience over time. Yet, given that it's difficult to accumulate age and experience any faster than time naturally passes, there are other techniques advisors can use to say "I don't know" or otherwise defer the question in ways that build an advisor's perceived competence and trust!

Mindset Shifts Around "Not Knowing"

Learning how to say "I don't know" in a way that builds trust often comes down to two elements: first, the advisor's mindset, and second, how the gap is communicated to clients.

Let's start with mindset. While the practicality of what to say and how to say it matters, the underlying feeling and intent matter even more. Being able to sincerely and confidently respond in the moment plays a huge role in how the message is heard and received by everyone in the room.

Consider a parallel example from sports. Whether it's kicking a soccer ball, spiking a volleyball, or serving a tennis ball, contacting the ball at the right place is crucial. But the setup, follow-through, and overall intent are just as important in determining the actual outcome. A tennis serve takes about 1.8 seconds. For approximately 1.7 of those seconds, the player isn't in direct contact with the ball – they're either setting up their body and racket for the point of contact or they're following through after the serve.

All of this to say: Yes, the words are important. But just as important is the body language and underlying sentiment behind the words, which can make a tremendous difference in how they're received.

"I Don't Know" Can Be Used To Build Trust!

At first glance, saying "I don't know" can feel like a loss of credibility. But, in reality, it's far better than giving a wrong answer. Very few clients expect their advisor to be a perfect encyclopedia of financial planning knowledge. More importantly, trust with clients isn't won or lost in a single moment. It grows and changes over time, especially in long-term advisor relationships.

A study by State Street Global Advisors and Knowledge@Wharton examined how advisors could strengthen client relationships and best communicate their value. It identified three levels of trust that clients seek in a financial advisor:

- Trust in technical competence and know-how;

- Trust in ethical conduct and character; and

- Trust in empathetic skills and maturity.

While it can seem like acknowledging uncertainty will detract from perceived competence, this is where a mindset shift can be key. Not knowing something on the spot can actually be an opportunity to demonstrate expertise – just after the call or meeting, rather than during it. When handled well, a moment of uncertainty can strengthen trust across all three levels:

- Technical competence: by researching and following up with the correct information.

- Ethical conduct and character: by choosing to defer the answer to ensure complete and accurate guidance.

- Empathy and maturity: by asking thoughtful clarifying questions in the meeting and following up promptly.

In short, part of what makes an advisor trustworthy is the ability to sift through complex information and give good advice – even if that process happens after the meeting. The value of thoroughness and due diligence can go a long way in reinforcing an advisor's credibility over time, even if the follow-up takes place after the meeting!

Reducing Meeting Anxiety By Focusing On Reported Problems

Occasionally, advisors may experience more intense anxiety about saying "I don't know" to clients. This may be rooted in feelings of impostor syndrome ("Now everyone is going to find out I don't actually know what I'm doing"), the pressure to prove oneself, or in memories of difficult past work experiences. While it's natural to reflect on meetings and learn from them, this anxiety can sometimes lead to over-preparing for calls (it is possible!) or replaying and second-guessing every detail of the conversation long after the meeting has ended.

It's true that some degree of stress and nervousness is part of the learning process. As Billie Jean King famously said, "Pressure is a privilege", and growth rarely happens without it. But if anxiety around client meetings begins to interfere with the advisor's ability to progress, it may help to shift focus to reported problems.

In other words, unless something has been specifically mentioned as an issue – whether by a manager, a client, or in the advisor's own clear observations – it may be helpful to assume that it's not an issue. Feedback from others and intentional self-reflection will still provide plenty of opportunities to improve. But reducing the background noise of self-doubt can make it easier to stay present in meetings and direct energy toward changes that truly matter, rather than concerns that may stem only from a lack of confidence.

For example, take the delivery of financial advice in the meeting. Advisors generally aim to communicate clearly and concisely and to notice when a client may have unexpressed questions or reservations. A level of mindfulness and self-reflection is helpful for reaching the next level of client meeting skills, and the advisor will ideally obtain continual positive and constructive feedback from clients and colleagues. However, if taken too far, the fear of making a mistake or fumbling with an explanation could become paralyzing. Ironically, if an advisor begins to avoid those opportunities due to nervousness, it can reinforce the perception that meetings are something to fear.

There are several ways advisors can strengthen the skill of delivering financial advice, such as asking more senior advisors for feedback, practicing with peers, or taking classes on public speaking. Ultimately, if the advisor isn't getting substantive feedback and is making a reasonable effort to improve those skills, there is little more to do than to keep practicing and learn how to manage the (very human) feelings of discomfort.

The reality is, there will always be a learning curve, especially in the early stages of an advisory career. Remembering that one imperfect moment in a meeting is just a small part of the broader client relationship – and the advisor's long-term development – may help ease some of the pressure.

Saying "I Don't Know" With Confidence

While mindset is essential, it also helps to have practical tactics for responding and following up when a question comes up that the advisor doesn't know the answer to.

First, in the meeting itself: Take a deep breath if anxiety spikes. Next, say something to acknowledge the question positively and request permission to ask follow-up questions. For example:

That's a really good question. I have a good idea, but I want to verify before I answer for sure. Do you mind if I ask you a few more questions, just to make sure we're on the same page when I look into things after this meeting?

This response works because it doesn't necessarily belabor the point that the answer isn't immediately available. Instead, it emphasizes what the advisor is going to do about it. Furthermore, asking follow-up questions also helps confirm the client's details and ensures that the advisor will follow up with research is tailored to the client's specific situation. In general, two or three clarifying questions are usually enough.

After gathering those details, the advisor can say:

Thanks for the extra information – this is really helpful. I'll look into this after our call and send you what I find by [time]. Would that work for you?

The time commitment can vary depending on the complexity of the question. Most of the time, following up within a day or so is ideal. If the information requires input from someone else, be transparent about that as well. For example:

I'll make sure our tax guy takes a second look as well, so that means I'll send you a follow-up on Friday!

Here are a few other phrasing options to consider:

That's a great question. I don't have that information on hand, but I'll gather it for you after our meeting. Does it work if I send it by [time]?

I'm glad you brought that up. I don't want to slow our momentum here, so if it's okay with you, I'll review the numbers in more detail after our meeting and follow up in [timeline]. In the meantime, let me ask a few clarifying questions to make sure I get to the bottom of this for you.

Try a few different approaches until something feels comfortable and authentic. Over time, these responses will start to feel more natural. In most cases, clients won't make a big deal of it – unless the advisor does. Adding a bit of humor can help, but be cautious about suing too much self-deprecation, especially in a career when credibility is still developing.

Following Up With Confidence

When it's time to follow up, things can be kept fairly simple. The most important thing is to honor the commitment made in the meeting – both in timing and content. Setting a realistic deadline upfront makes this much easier.

A good follow-up email could look like this:

Hello [Client(s)],

Thank you for your patience while I looked more deeply into [question that came up]. I checked [source], and based on what you described about [meeting talking point 1] and [meeting talking point 2], here's what I found:

[Brief explanation]

For more detail:

[Provide a more in-depth explanation]

In summary, this means that if we'd like to move forward with this strategy, we'll need to [action items – be clear about who will do what and deadlines].

Please let me know if you have any further questions or would like to set up a call to discuss this in more detail. [Meeting link]

Best,

[Advisor]

Advisors can also record a short video to explain their findings, especially if the answer is particularly nuanced. In that case, consider adding a line like:

To help explain this more clearly, I've recorded a video you can watch here [link]. There's a lot of detail, so please don't hesitate to reach out if you'd like to discuss further.

In short, communication that is warm, professional, and focused on the client's needs is an achievement in itself, and a powerful way to build trust over time!

Final Reminders And Next Steps

Advisors looking to develop this skill further may want to practice in mock calls, particularly with senior advisors or mentors who likely experienced similar challenges earlier in their careers. If a senior advisor will be in a meeting with the associate, it can help to develop a game plan in advance for how to tag-team responses together.

While there will always be opportunities to learn new things, questions that come up repeatedly can be a useful sign to dig in deeper! If the same topic keeps coming up, it may be worth taking time to study it in more depth or adjust how meeting prep is handled.

For information that's difficult to recall on the spot, consider keeping a reference handy. And for common questions that require some client education, it can be helpful to create a client-friendly handout or write a blog post. That way, the material is ready to share after the call as a helpful resource.

Ultimately, the key point is that sometimes saying "I don't know" can feel stressful, but it doesn't have to be. When an advisor remains positive and confident, these moments can become opportunities to demonstrate thoughtfulness, competence, and thoroughness – and to keep developing their expertise over time!

Leave a Reply