Executive Summary

Asking good questions is an essential tool for financial advisors. From building rapport with prospects, to gathering information needed to create a plan, and to offering support for nervous clients during market downturns, effective conversation skills – including asking good follow-up questions – can enhance not only an advisor’s value but also the client’s experience. But while advisors are used to asking questions of prospects and clients to get a conversation started, they might think less often about crafting follow-up questions once they receive a response. Which is potentially the most important part of the data-gathering process, as it turns out that effective follow-up questions can not only lead to more productive client conversations but also help make the advisor more likable!

One of the distinguishing features of a true follow-up question is that the question is asked with the singular goal of learning more about the speaker – there are no hidden agendas (intentional or subconscious) to talk about oneself or anything else, as tempting as that can sometimes be. For advisors, that means that good follow-up questions solicit information about the client’s experience from the client’s own point of view.

Another way to characterize a good follow-up question is to think of data-gathering questions. Advisors very commonly get surface answers from clients when they ask initial questions to open a conversation, but good follow-up questions can draw out the client’s deeper concerns. For example, an advisor working with a client who says they are worried about being able to afford retirement could ask a series of follow-up questions exploring issues such as when the client plans to retire and what plans they have for retirement that might be unaffordable. These follow-up questions dig deeper into the retirement picture and aim to understand the fear the client has expressed.

Not only can good follow-up questions help an advisor gather data, but they also demonstrate responsiveness to prospects and clients. In fact, a 2017 Harvard Business School study found that follow-up questions that are more responsive to the person being asked questions are generally more valued than other questions and statements that fail to focus on the person individually. So for advisors, follow-up questions can be an effective way to validate a client’s concern and show understanding without judging (positively or negatively) what the client has said. In other words, great follow-up questions allow advisors to connect with clients, gather information without placing judgment, and can create more likability even during tough conversations, regardless of whether the advisor agrees with the client.

Ultimately, the key point is that follow-up questions can be just as important as the questions used to kick off a conversation. Effective follow-up questions not only help advisors gather better client data, but also demonstrate responsiveness to prospects and clients alike. And because asking good follow-up questions is a skill that can be developed, it can be helpful for advisors to practice frequently, both inside and outside of the office!

What Makes A Good Follow-Up Question?

It sounds simple enough – a follow-up question is one that asks a bit more about something the speaker has just told you. But how can we think more concisely about what makes a truly good follow-up question, especially when it comes to working with clients? One way to categorize a true follow-up question is that it is asked with the singular goal of learning more about the speaker – there are no hidden agendas (intentional or subconscious) to talk about yourself or anything else, as tempting as that can sometimes be. For advisors, that means that good follow-up questions solicit the client’s experience. Stated differently, we want to employ an overt solicitation of information from the client so as to keep the focus only on what matters most to the client and to help make talking about finances a bit easier – it is easier to talk about oneself (because, theoretically, we know ourselves better than anyone else) than talk about concepts or ideas that are unfamiliar.

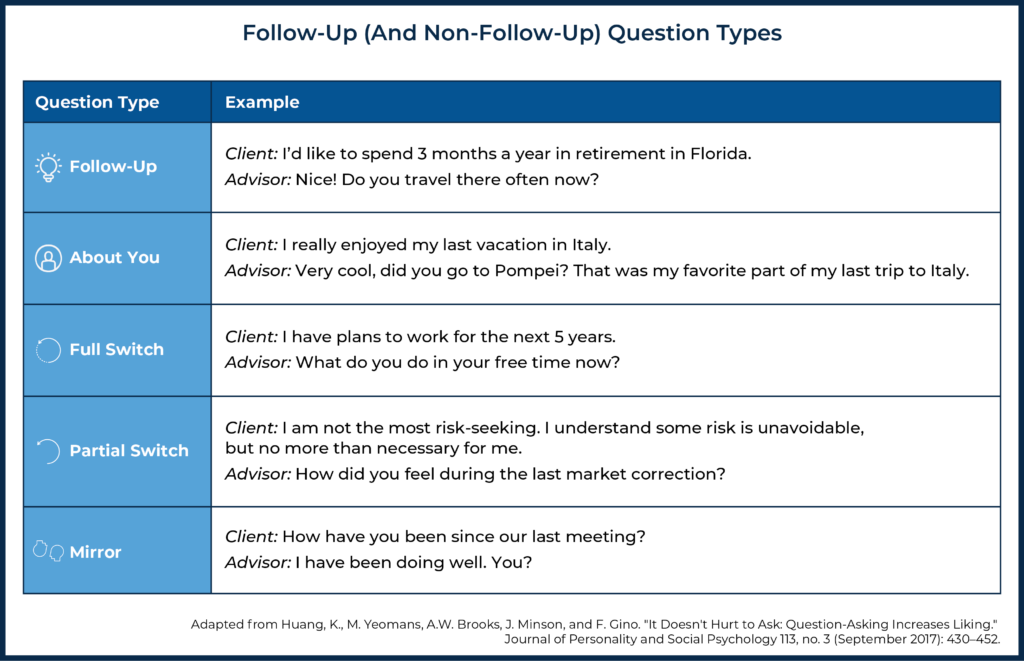

Yet, in actual conversations, we do not always ask good follow-up questions. In fact, in a 2017 Harvard Business School study led by Alison Wood Brooks and Francesca Gino, researchers suggested that while it’s common to ask a question that follows up after a conversation, the tendency is to do so only so that the questioner can relay their experience on the topic – because again, people are typically most comfortable talking about themselves and their own experiences. Imagine a client who says that they spent their vacation in Italy. An advisor might respond by saying, “Super cool, did you go to Pompeii?” Regardless of how they answer, the advisor really only asked so that they could share that they went to Pompeii and that it was great. Which is very different from asking a follow-up question about the client’s travel, for the sake of soliciting information about the client’s experience without the need for the advisor to shift the focus to their own experience.

If you’re thinking, “Wow. I’ve done that... should I not have done that? I thought I was just swapping stories and building rapport.” First, you are normal and you were building rapport; it just wasn’t being done through the use of a true follow-up. Second, rather than tell yourself, “Don’t do that anymore!” it’s more important to be aware of the questions you’re asking and how those questions will shape the ensuing conversation. As discussed later, swapping stories as a response does not necessarily result in a negative outcome, but it may not reflect the same level of responsiveness typically associated with true follow-up questions. When the end goal is to build more trust and connection with the prospect, responding in a way that ends in talking about ourselves will be less effective.

Another common way that follow-up questions fail from staying focused on the person being spoken to is by asking questions that change the subject. For example, perhaps the advisor switches the conversation about Pompeii and suddenly asks the client what brought them in today without engaging at all with their comment about their trip to Italy. This might cause the client to feel as if the advisor doesn’t really care about anything other than getting down to business, and might make it difficult for the client to be convinced that the advisor really has their best interest at heart.

A third way that questions fail as good follow-up questions is when someone simply mirrors or repeats the question originally asked. For example, if a client asks their advisor how they are doing, the advisor would be mirroring if they simply answered briefly and then asked the client how they are. This conversation won’t necessarily go any deeper if mirroring continues to be used; instead, the information exchanged will probably stay very superficial and may not be helpful for the advisor to get a better understanding of their client.

In the table below, only the first question is a true follow-up question. The rest are examples of the subtle ways we commonly change the follow-up into something else.

Nerd Note:

Why are we so inclined to talk about ourselves? It is normal for us to want to talk about ourselves and our talents. At the simplest level, we know ourselves better than anyone else, so talking about ourselves can feel easier than trying to talk about the experience of someone else. From a sales perspective, we talk about ourselves because that is one way we tend to be socialized to demonstrate value – I should be your advisor because I have X, Y, and Z experience.

Another way to characterize a good follow-up question is to think of data-gathering questions. Advisors very commonly get vague or superficial answers from clients when they ask introductory questions meant to encourage deeper conversations.

Advisor: What is keeping you up at night?

Client: Will I be able to afford retirement?

There is nothing wrong with what the advisor asked here, nor how the client responded. It’s a good way to lead into a conversation, but it doesn’t tell the advisor very much, at least initially. But asking the appropriate follow-up questions that keep circling back to retirement and focusing on what is important to the client can help the advisor learn both about when retirement is and what the client thinks they will do in retirement that would or could be so expensive they would be unable to afford to do it.

For example, some good follow-up questions the advisor could use next might include:

- When are you planning on starting retirement?

- What activities are you concerned with being able to afford in retirement?

- What have you currently saved for retirement?

- What do you expect your expenses to be in retirement when compared to now?

All of these follow-up questions dig deeper into the client’s unique retirement picture and aim to understand the fear the client has expressed. Importantly, the follow-up questions do not change topics, they purposefully reuse the same language that the client used (i.e., “retirement”), and the advisor doesn’t try to connect the client to what other clients may be doing (e.g., the advisor doesn’t tell the client that many of their other clients retire around age 68).

In other words, follow-up questions can be great data-gathering questions as they allow advisors to do just that – gather more data, both qualitative and quantitative, about the client and where they are in their financial journey.

Follow-Up Questions Don’t Just Get You More Information, They Actually Make You More Likable!

If making the conversation easier and gathering great data alone aren’t enough to convince advisors to consider how they’re asking follow-up questions, another great thing about good follow-up questions is that they can also help the advisor be more likable. According to the 2017 Harvard Business School research study, the use of follow-up questions during speed-dating events was assessed and how they played a role in whether someone was more or less likely to get a second date. The study found that individuals who asked more true follow-up questions – focusing on the other person’s feelings and experiences – got more second dates than those who used mirroring questions, switch or partial switch questions, or questions emphasizing their own experiences (instead of those of the person they were talking to). Which suggests that people who ask true follow-up questions can tend to be more likable.

It is worth noting that other forms of follow-up questions didn’t necessarily cause the speed-dating participants to dislike each other, they simply didn’t do as much as true follow-ups to move the needle on likability (for instance, as mentioned earlier, swapping stories with a prospect wouldn’t necessarily result in someone liking their advisor less, they just may not be as effective in increasing likability). Which means that there is really no harm in asking those other questions, because eventually you may need to use a full-switch or partial-switch question to change topics. But when an advisor is meeting with a prospect who is deciding whether they want to sign up – using true follow-up questions to better understand the prospect’s hesitation and concerns can be the advisor’s best course of action.

Furthermore, think about other conversation rules you have heard, for example, the “70/30 Rule” of listening 70% of the time and only talking 30% of the time. If the advisor encourages the prospect to talk more, the advisor will more likely understand specifically what they need and, at the same time, can help the prospect further understand how the advisor can be of value to them. If the advisor does all the talking, they may be saying important things, but it will be hard to gauge whether the client understands or cares without getting their input. A conversation that engages the prospect in the discussion tends to be a more powerful experience – not only does the prospect have the opportunity to give voice to their concerns and worries, but the advisor also has the opportunity to validate the prospect’s feelings and to help them understand how their services can cater to their very specific needs. Moreover, if advisors struggle to do this in prospect meetings because they are overcome with a need to sell or demonstrate their value – asking a set of good follow-up questions can be a good strategy to use. Asking a lot of follow-up questions doesn’t just show value – it is the value.

Why are good follow-up questions so valuable? Follow-up questions show that you care, that you are paying attention, and that you are interested in who the other person is and what matters to them. Which is important, because everyone likes to believe and feel that they are interesting!

Furthermore, money is a tough subject for many people to discuss. It can be very uncomfortable for clients to have conversations about their personal finances, even if that is what they know they are in your office to discuss. Money can be a loaded subject for many people, as it carries with it morals, ethics, beliefs, family, power – and just about anything else you can think of. So any indication to a client or prospect that the advisor isn’t interested or doesn’t care about their feelings and values around money can shut them down very quickly.

Consider a client who says this to their advisor:

Client: I’m not feeling great lately, that is why I called – I’m nervous about my ability to retire with the crazy inflation lately. I’m not sure if I am invested correctly anymore.

Depending on how the financial advisors answers, the ensuing conversation can go in very different directions. Imagine how the client may respond to and feel about these two very simple responses:

Advisor #1 Response (Partial switch): Inflation is crazy. Are you thinking about changing your asset allocation?

Advisor #2 Response (Follow-up): Inflation has jumped. Can you tell me more about what you mean by 'invested correctly'?

Again, neither response is necessarily wrong. Yet, the response from Advisor #2, the true follow-up question, will be much more effective not only in helping the client feel heard, but also in demonstrating the advisor’s interest in learning about their perspective.

In the Harvard study, researchers characterized the value of follow-up questions as responsiveness. Follow-up questions that show care and interest are responsive and are generally more valued than other questions that fail to focus on what’s important to the client or prospect. Consider again the two responses to the client who was nervous about inflation and questioning whether his investments still made sense. While the first response stays on the same subject of the discussion – asset allocation is related to how the client is invested – it is really a partial-switch response because it is now asking about something that isn’t coming from the client and their own experience. In the first response, the advisor is responding more with their own thoughts, and not the client’s. The advisor is very comfortable talking about asset allocation as a solution, and thus finds it easier to offer a response with something they are more confident talking about.

Yet, while changing the client’s asset allocation may be the solution to designing a more balanced portfolio, the real area of concern is the client’s anxiety around retirement and the current economic environment. So the question around asset allocation may eventually be the right way to start a discussion with the client, but at this stage in the conversation, a true follow-up question would focus more on the client’s anxiety and understanding the specific source of their feelings. Which is what the second response does –asking what the client means by “correctly invested” can help the advisor identify and better understand the client’s specific pain point. And this tends to be more difficult, because being responsive means paying attention and intentionally focusing on asking about things we may not be comfortable or knowledgeable about. The advisor probably knows exactly what the client’s asset allocation should look like, but they don’t necessarily know what it means to the client to be “correctly invested”.

Thus, while Advisor #1 asks a question on a topic that the client has not indicated is within his experience and probably won’t be able to discuss in much depth, Advisor #2 asks a follow-up question about something that is within the client’s own experience that will help the advisor better understand the client’s unique point of view.

Notably, demonstrating responsiveness is more about understanding the client; it does not mean that the advisor must agree with the client. Consider the following exchange:

Client: I’m not feeling great lately, that is why I called. I think my portfolio allocation needs to be less risky.

Advisor: I hear you – the market volatility is tough to stomach. What about this market swing in particular has made you uncomfortable?

In the exchange above, the advisor has not agreed to anything. Instead, the advisor has asked a thoughtful follow-up question, displaying responsiveness to the client’s situation and feelings. The advisor has effectively validated the client's concern and shown understanding, but at the same time has never judged (positively or negatively) what the client has said.

In other words, great follow-up questions allow advisors to connect with clients, gather information without placing judgment, and can create more likability even during tough conversations, even though the advisor may not agree with the client.

Flawless Follow-Ups For Financial Advisors

Some advisors have described asking good follow-up questions as challenging, believing that they just sound and feel awkward. Some have noted that they tend to ‘freeze-up’ when trying to ask a good follow-up question. For many of us, using the phrase, “Tell me more about that” over and over again doesn’t always sound right in the moment and, when used too much, can even start to feel disingenuous. But when advisors know how to ask the right follow-up questions that feel natural and appropriate, they may find it is much easier to use them with their clients.

Here are a few follow-up questions that advisors may find helpful to use with clients, and that would also be appropriate for use in prospect meetings:

When talking about the pain-point(s) that brought them to the advisor in the first place:

-

- Why have you decided to come in now to address the issue (bonus points: use the actual words from the client in lieu of saying “the issue”)?

When talking in generalities about retirement:

-

- When do you want to retire? How much do you think you will need to retire?

When providing details about their current financial situation:

-

- What have you done in the past to keep tabs on all of your money?

Some advisors also worry they will be perceived as being pushy or invasive by asking too many follow-up questions, especially with prospects or new clients. In these instances, it’s okay for the advisor to simply state their concern about sounding pushy or invasive. Sometimes it can be better for the advisor to just come out and say how they’re feeling to clear the air, instead of worrying about it. Again, clients can be very uncomfortable talking about money, so if the advisor is worried about asking questions, it can help to take a moment to put everyone at ease by addressing the elephant in the room.

For example, when asking a client why they have decided to come in now to discuss their particular pain points, an advisor can follow up with something like this:

I don’t want this next comment to sound judgmental or invasive – money is a very loaded topic. So please know when I say, I am curious to know why now seems like the best time to address this issue as opposed to six months ago, I am just that – I am curious to learn more about you.

Feeling nervous about asking the right follow-up questions is natural – especially for advisors who aren’t accustomed to focusing on the follow-up questions they ask clients. It can take time for some advisors to gain confidence in thinking on their feet and to get good at always having the right follow-up questions ready to ask clients at just the right time.

Advisors may find it helpful to use an agenda to help them come up with good follow-up questions in advance. For advisors who like to avoid unpredictable meetings, an agenda can also be used to guarantee some level of predictability. An agenda can be as simple as the following:

PROSPECT MEETING AGENDA

- Top three reasons why you want to work with a financial planner now.

- Three things you have tried or are trying when it comes to managing your finances and goals now.

- Top three questions you have about the process of financial planning and how we work together.

Send this to the client and request that they send their responses back before the meeting. This gives the advisor a chance to prepare a few follow-up questions based on the client’s own experiences and concerns before they ever sit down with them. The agenda does not need to be formal or lengthy; instead, it can follow a very simple format and offer the advisor and client a lot of flexibility.

Furthermore, people tend to like agendas! A little structure can go a long way with setting expectations, which can provide much-needed comfort when having stressful discussions.

Imagine the following:

Sally has never met with an advisor before. She knows she needs help, so she has contacted an advisor in her area.

After scheduling a meeting, the advisor sent a short email noting that they were looking forward to meeting her. While she appreciated the message, there was nothing to help her understand how the meeting would go or what the advisor would ask her.

What should she prepare? What could the advisor actually do to help her? Are they going to think she is dumb for needing help?

Prospects without any sort of structure can get themselves worked up with anxiety around meeting with an advisor for the first time. However, providing a simple agenda, like the one outlined earlier, can help to ease some of these emotions for the client – and if they write out their answers and provide them to the advisor in advance of the meeting, it allows the advisor to prepare appropriate questions, easing some of the stresses around using follow-ups.

Another suggestion to help advisors new to asking follow-up questions is to post some visual reminders to do so. Something as simple as framing a desktop quote about follow-ups can help the advisor remember to use them and may even prompt clients to ask about the quote. This can give the advisor an opportunity to explain why follow-up questions are so important, and to address some of the concerns the advisor has about asking them.

Advisors can also write the words “follow-up” on the top of each page of a notebook that they take into meetings. They can explain to the client the importance or practice of taking notes and so then, each time the advisor looks down to make a note, the reminder to ask a follow-up on whatever was just so important that it needed a note.

Lastly, practice asking follow-up questions with spouses, partners, friends, and kids. Being mindful to always ask at least one follow-up in every conversation can help advisors to develop that ‘muscle memory’ of asking good, responsive questions. Slow down and focus on asking people that you care about good follow-up questions. It shows that you love them and that you are being responsive to them, and it is also great practice. Imagine a dinner-table conversation where each member of the family is asked to share something about their day, and then asking each person a well-formed follow-up question to continue the conversation.

Sounds nice to me! 😊

Follow-up questions make prospects and clients feel understood and they help advisors gather important information that they need to build relevant financial plans. Yet, what constitutes a true follow-up question, especially one that can promote likability, is more nuanced and requires the advisor not only to pay attention to the client’s feelings and values, but sometimes to ask questions that are unfamiliar and uncomfortable.

And while getting good at asking true follow-up questions can take time and energy, asking responsive questions that give the prospect or client a chance to share personal experiences from their own point of view are the most valuable for all parties involved – because strengthening the client relationship and building trust are the best ways to truly understand how best to service clients!

Great article. What resources (either books or articles) do you recommend to help develop my skills in this area of question-asking? Thanks in advance!

First, thanks. This whole series on communication is taking me practice to a higher level because I am engaging in a more thoughtful way.