Executive Summary

Because financial advisors often work with clients for many years or even decades, it's not uncommon for them to encounter client couples who decide to divorce. Marital conflict between clients can create a host of ethical dilemmas for financial advisors – situations that, if mishandled, could lead to breaches of fiduciary duty or even disciplinary actions from governing bodies such as CFP Board. Recognizing the prevalence and complexity of these issues, CFP Board has released guidance on how advisors should navigate divorce and other marital conflicts in alignment with the Code of Ethics and Standards of Conflict. Given the high stakes of managing these situations, advisors benefit from understanding the ethical challenges that can arise, knowing their firm's policies and fiduciary obligations to both spouses, and proactively addressing potential conflicts of interest before they occur.

Notably, working with client couples involves ethical considerations, even when the couple's relationship is strong. For instance, an advisor may communicate more frequently with the spouse who is more financially involved, while the other partner might not attend regular meetings. Over time, this can lead to advice or financial plans that don't reflect the preferences of both partners and, in some cases, to transactions that one spouse might disagree with (which could ultimately lead not just to conflict for the couple but to liability challenges for the advisor, as well). With this in mind, engaging with both partners consistently, clarifying how accounts are structured, and maintaining strong documentation practices – including accurate and comprehensive meeting notes – can help advisors ensure they are fully meeting their fiduciary obligations.

When a client couple does announce they're planning to divorce, advisors must decide how to work ethically with one or both partners while adhering to the terms of their engagement letter, firm policies, and all relevant compliance requirements. One helpful approach is to outline the options for how the advisory relationship may proceed and to immediately review current withdrawal authorizations on all accounts under management.

If both spouses choose to continue working with the same advisor, the engagement scope should be formally redefined. This step provides clear and transparent communication to both parties about what services the advisor will and will not provide during the divorce process. Nevertheless, even if an advisor strives to remain neutral, offering advice to only one spouse – or maintaining more frequent communication with one over the other – can create a disadvantage for the other. Advisors must carefully consider whether they can truly remain impartial, particularly if they have developed a closer relationship with one spouse.

If the advisor continues working with only one spouse, the joint engagement must be formally terminated and replaced with a new agreement with the remaining client. Once the new engagement is established, confidentiality becomes even more critical, as the advisor must avoid disclosing information shared by the departing spouse during the prior joint engagement. Upholding privacy not only reinforces fiduciary duty but also demonstrates professional integrity during what's often an emotionally difficult time for clients.

Ultimately, the key point is that divorce can create upheaval not only in a couple's relationship but also in the advisor-client relationship, presenting new ethical challenges around privacy, loyalty, and scope of engagement. Establishing clear structures – from documenting actions and decisions to defining firm policies for handling marital status changes – helps advisors uphold their fiduciary duty, protect client trust, and minimize the risk of regulatory or disciplinary consequences.

Divorce creates a fragile environment for a family, creating both intense emotional and financial upheaval for all involved. For financial advisors, this situation is also ethically complex, underscoring the need for greater focus on maintaining one's fiduciary duty to both spouses. CFP Board's newly released Divorce Guide outlines the issues that can arise when working with married couples in conflict and emphasizes the importance of managing marital conflicts of interest. Noncompliance with the CFP Board Code of Ethics and Standards of Conflict can result in disciplinary action, including public or private censure, or suspension or revocation of a CFP professional's right to use the CFP marks.

Divorce creates a fragile environment for a family, creating both intense emotional and financial upheaval for all involved. For financial advisors, this situation is also ethically complex, underscoring the need for greater focus on maintaining one's fiduciary duty to both spouses. CFP Board's newly released Divorce Guide outlines the issues that can arise when working with married couples in conflict and emphasizes the importance of managing marital conflicts of interest. Noncompliance with the CFP Board Code of Ethics and Standards of Conflict can result in disciplinary action, including public or private censure, or suspension or revocation of a CFP professional's right to use the CFP marks.

While advisors seek to act in their client's best interests, CFP professionals must understand and apply CFP Board's fiduciary framework, which includes three core principles: the duties of loyalty, care, and following client instructions. During marital conflicts, each of these three duties may be at a heightened risk of breach. For Registered Investment Advisers (RIAs), SEC standards also require disclosure of all material facts and prohibit misleading statements – obligations that may likewise be challenged during periods of marital conflict.

When a couple's goals and lives are no longer aligned – leading to a desire to dissolve the relationship, how can advisors continue to honor their fiduciary duty not to a partnership, but to two individual people? The answer lies not only in the advisor's regulatory and compliance requirements or the specific circumstances of the client, but also in recognizing the broader ethical concerns of working with couples.

When couples experience marital conflict – whether minor disagreements about risk tolerance or major disputes leading to divorce – the ethical challenges of advising them often come to light, though not always with clear solutions. Yet, these same challenges often exist long before any visible conflict arises, making it easy for the ethical considerations of working with couples to go unnoticed. Failing to acknowledge these dynamics can leave ethical blind spots unaddressed, leaving advisors vulnerable to fiduciary lapses and future conflict within both the client relationship and the couple's relationship itself.

Ethical Dilemmas Working With Couples

It's common for financial advisors to work with married couples as a part of their practice. However, it's also common for advisors to interact more frequently with one partner than the other. Fidelity's 2021 Couples & Money Study found that only 38% of respondents meet with their advisor together, suggesting the majority do not. This is consistent with previous findings published in the Journal of Consumer Research indicating that many couples divide financial responsibilities, with one partner often serving as the designated family "CFO".

For example, one spouse may manage the daily budget while the other oversees long-term investments, or the partner with higher financial literacy may make most of the financial decisions. While these arrangements may seem intuitive and efficient, they can also create ethical challenges for advisors.

When one spouse is significantly more engaged with the advisor, it often leads to a closer relationship with that individual. But this dynamic can be detrimental – both ethically and operationally – leading not only to potential fiduciary oversights but also to lost assets after the death of the primary contact. In some instances, advisors may not even recognize that they are actually serving both spouses rather than just one.

Consider, for example, an advisor in Texas working with James and Maria as clients. The advisor manages an IRA owned by James and valued at $1.2 million – the couple's largest asset. On paper, James is the sole account holder. However, because Texas is a community property state and this account was funded throughout the couple's marriage, half its value legally belongs to Maria, even though her name does not appear on the account statement. If the advisor treats this account as solely James's and consults only with him about decisions made in the account, they may be disregarding Maria's legal interest.

An integral part of financial planning involves understanding a client's goals, risk tolerance, objectives, financial status, and personal circumstances. For CFP professionals, these key integration factors – outlined in CFP Board's Standards of Conduct – guide how advisors fulfill the fiduciary duty of care. When an advisor fully understands only one partner, they may not be getting a complete picture of what's truly in the other partner's best interest, or even aligned with their goals and values.

Many individuals choose to marry someone with different traits than themselves: a spender marries a saver, a risk-taker marries someone more risk-averse, or a satisficer marries a maximizer. When advisors primarily engage only one spouse, they may assume they understand the couple's shared goals and values, when in reality, they're only hearing one perspective. Research shows that spouses often have different financial values and stressors.

Relying solely on one partner when making assumptions about partner alignment on financial decisions can potentially lead to uninformed consent – when clients agree to actions without a full understanding of the implications or conflicts of interest.

To uphold their fiduciary integrity, advisors must manage potential conflicts of interest within the couple, especially when a financial decision benefiting one spouse may adversely affect the other.

Consider the example below, from CFP Board's case histories, illustrating how obtaining consent from only one spouse can create an ethical conundrum – and ultimately lead to disciplinary action.

A CFP Board Case Example: Failure To Obtain Consent From Both Spouses

A CFP professional had worked with a couple for over 20 years. The husband, whom the advisor had known for over 30 years, was the advisor's primary point of contact and handled nearly all communications with the advisor, consistent with the wife's earlier instructions. Relying on this arrangement, the advisor excluded the wife from communications about an insurance policy she owned and had purchased through the advisor roughly 17 years prior.

Over the years, the husband disclosed to the advisor that he was unhappy in the marriage, had an extramarital relationship during business trips, and was considering divorce. The advisor never disclosed to either spouse the potential conflicts of interest that could arise if the couple were to divorce – although he did inform the insurance company that the couple might be divorcing.

Shortly thereafter, the husband told the advisor that he had been diagnosed with throat cancer and requested a $55k partial distribution from the couple's insurance policies, with the proceeds deposited into his new personal checking account. The advisor suggested three ways to obtain the funds – from the policy that the husband owned and from the policy that the wife owned – and reasoned that a distribution from the wife's policy would make sense because it was the only policy with any cash value. The advisor did not include the wife in any of these discussions.

Moving forward with the decision to make a partial distribution from the wife's policy, the advisor provided distribution paperwork to the wife requesting her signature and a voided check for her checking account. After some back-and-forth with the husband, the advisor received the completed forms – bearing what appeared to be the wife's signature – and submitted them to the insurance company without contacting the wife directly. Through the insurance company's due diligence, the wife was contacted to confirm the documentation, given the pending divorce and their residence in a community property state. At this point, she revealed that she had neither signed the forms nor authorized the distribution. The company determined that the husband had forged her signature.

The wife subsequently filed complaints with several regulatory bodies, alleging that she had been the victim of financial abuse. Although CFP Board recognized the husband's deception, it concluded that the advisor had breached his fiduciary duty of loyalty and care by failing to manage the conflict of interest between divorcing clients and by failing to obtain informed consent from both spouses. The advisor received a private censure and was required to complete 60 hours of remedial continuing education.

Marital Conflict Or Dissolution Heightens The Ethical Challenges Of Working With Clients

The advisor-client relationship is an intimate one. Advisors are privy to many aspects of their client's life, from their dreams to their failures, and they're often trusted partners through major life transitions. Due to this closeness, financial advisors may recognize signs of marital conflict even before family members do. Sometimes, they may even anticipate a divorce – either because one partner discloses concerns or because inconsistencies in financial data hint that something is amiss.

Consider the following example:

Example 1: Michel is a financial advisor preparing a financial plan for a long-term client couple, Daniel and Lauren.

Michel notices that the client's reported income and expenses should result in significant excess cash for savings. Yet, after reviewing account balances, he sees that the client's net worth is decreasing.

When he points out the discrepancy, Daniel reluctantly admits that he has been losing money on sports betting and hasn't told Lauren because he hopes to win it back soon. He didn't want to worry her, and she rarely checks their accounts anyway.

In the example above, one spouse has put Michel in an awkward position by making him party to Daniel's financial infidelity – where one partner is concealing, misrepresenting, or withholding financial information or decisions from the other. While Michel isn't necessarily responsible for disclosing this information to Lauren, continuing to withhold it would also mislead her, creating an ethical dilemma around informed consent and loyalty.

Clients Dissolving Their Relationship

When marital conflict leads to divorce, significant changes to the advisor-client relationship occur. Advisors have options for how to work ethically with one or both partners, but they must do so in accordance with the terms of their engagement letter, firm policies, and all relevant compliance requirements. Above all, advisors should act to avoid harming either client.

One way advisors can position the changes in the relationship is to outline the options for how the relationship can proceed. This provides clear and transparent communication to both parties about what they can and cannot expect from their advisor during this transition. An immediate key step to take is reviewing the current withdrawal authorizations on all accounts under management.

Pop culture is full of stories about divorcing couples, where one spouse takes revenge on the other by draining joint accounts, leaving them surprised and scrambling. These scenarios might make for fun song lyrics and movie scenes, but in reality, actions like this would represent a fiduciary failure. Advisors are obligated to follow the instructions of their client – but what if those instructions are intended to harm the other spouse?

To prevent these situations, advisors can proactively review account withdrawal authorizations with both partners and establish a policy of requiring consent from both clients before any withdrawals are made. Documenting this shared consent helps ensure transparency and protects both the advisor and the clients. If an advisor cannot determine a clear path for handling these client requests during the early stages of a divorce, they can seek guidance from their compliance department or legal counsel.

As the client's relationship changes, the advisor will need to adapt their engagement to continue to serve the client while also meeting compliance, regulatory, and fiduciary standards. This may include redefining the scope of the engagement, confirming account ownership, establishing the information that can be shared between spouses and what should remain confidential, and updating client agreements.

Working With Both Partners Of The Divorcing Couple

If both spouses choose to continue working with the same advisor, the advisor may need to establish a new scope to the engagement. CFP Board's newly released Divorce Guide recommends avoiding advice directly related to divorce proceedings – such as property division, spousal maintenance, and child support – since these matters would be determined by the court. Any advice on these issues could constitute a material conflict of interest requiring full disclosure to both spouses, and could potentially violate the advisor's fiduciary duty of care and loyalty by advantaging one spouse over the other.

Even if an advisor strives to remain neutral, giving advice only to one spouse may disadvantage the other spouse. Advisors must consider whether they can truly remain impartial, particularly if they have developed a closer relationship with one spouse.

An example of this situation can be seen in the August 2022 CFP Board case histories.

A CFP Board Case Example: Conflict of Interest Arising From Unequal Communication In Divorce

A CFP professional was working with a married couple when Spouse A informed them that Spouse B wanted a divorce. The advisor told both clients that they could reach out with questions regarding their financial plan or the potential impact of the divorce on their overall financial situation. However, the advisor did not disclose the conflict of interest created by continuing to provide financial advice to both clients during the divorce process.

Spouse B later reached out to the advisor multiple times for help reviewing financial affidavits from the divorce proceeding, assessing property division, and evaluating the marital settlement proposal. The advisor gave advice to Spouse B about issues they should discuss with their attorney, and offered thoughts on what Spouse B should request in the divorce.

Spouse A subsequently filed a complaint to CFP Board, alleging the advisor breached their fiduciary duty by communicating with Spouse B during the couple's divorce. The advisor reasoned that Spouse B had no financial background and knew very little about the couple's financial situation. Additionally, the advisor noted they had offered to assist both clients in the same manner.

CFP Board found the financial advisor in breach of their fiduciary duty as their duties to Spouse B were adverse to Spouse A's interests and that the conflict of interest had not been properly disclosed. The advisor received a public censure with a remedial work requirement of five additional hours of continuing education on fiduciary duty.

When serving both spouses during a divorce, advisors must be especially cautious about privacy and confidentiality, exercising greater diligence in making recommendations based on information not meant to be shared between the two spouses. Given these added complexities, advisors may determine that continuing to serve both spouses may no longer be feasible. They may also suggest other arrangements – such as suggesting that clients seek legal counsel or bring in a Certified Divorce Financial Analyst for guidance outside the advisor's core competencies – or help one or both clients transition to another advisor.

Working With One Partner Of The Divorcing Couple

If the advisor continues working with only one spouse, the original joint engagement with the couple must first be formally terminated and replaced with a new engagement for the remaining client. Documenting the termination of the relationship in writing should include the effective date of the termination, the reason, and a clear summary of how the relationship with the advisor is being redefined. Having both spouses sign these documents can help avoid legal exposure if one of the spouses later claims a breach of fiduciary duty.

Advisors can honor their relationship with the departing spouse with professionalism and goodwill by offering to provide recommendations for other qualified advisors who may be a good fit and by ensuring they receive copies of all relevant financial documents (e.g., financial plans, account statements) created during the joint engagement.

While this can be incredibly helpful to the departing spouse during their transition, confidentiality remains critical. The advisor must avoid sharing information disclosed by the departed partner during the joint engagement, even after the relationship has ended. Respecting each client's privacy helps advisors adhere to their fiduciary duty while upholding their professional integrity during what's often an emotionally difficult time for clients.

Practical Steps: Acting As A Fiduciary Before And During Conflict

While ethical dilemmas often emerge during moments of conflict, the groundwork for ethical decision-making is laid long before tensions surface. Advisors who build habits of clarity, inclusion, and documentation from the start are better equipped to navigate sensitive situations with confidence and integrity. There are many practical ways for advisors to maintain their fiduciary duty both before conflict arises and during periods of relationship strain.

Clarify Who The Client Is And How Their Accounts Are Structured

From the beginning of the client-advisor relationship, an advisor's due diligence should include a clear understanding of a couple's assets. This goes beyond account balances, asset allocation, and cost basis; it also includes ownership, titling, and the history behind each account's structure.

The example below shows how this can look in practice.

Example 2: Jordan Ellis is a financial advisor onboarding her new clients, Nina and David Morales. While reviewing the couple's account statements, beneficiary designations, and trust documents, she notices that one of the brokerage accounts – held at a different custodian – is in Nina's name only and carries a substantial balance..

During their collaboration meeting, Jordan presents the couple's balance sheet and gently notes, "I see this account is held separately at a different bank. Can you help me understand how this fits into your financial picture?"

Nina explains that the account holds an inheritance she received from her grandfather several years before the marriage and that their prenuptial agreement specifies this as her separate property. She keeps the account separately titled to avoid commingling it with marital assets. As Nina explains, David nods along, adding additional details about how their assets are structured.

Through this review and open discussion, Jordan learns several things about the family's financial life:

- The couple has a mix of joint assets and sizable separate property.

- They have a prenuptial agreement that she has not yet reviewed.

- Both spouses are aware of and seem comfortable with their asset arrangement.

This example above illustrates how early discussions not only help the advisor understand who must be consulted on specific accounts, but also give them a better understanding of the clients themselves. By raising questions about all accounts and assets with both partners in the meeting, advisors set a precedent for transparency and open dialogue.

Set A Precedent For Engaging Both Partners

Advisors can encourage collaborative engagement by intentionally engaging both spouses from the start of the relationship. Setting expectations for joint participation doesn't require major changes to a practice; it starts with clear communication of how the advisor works with couples.

Beginning with the onboarding process, an advisor might explain how they work with couples at their firm. This could include:

- Setting expectations that the advisor will meet with both members of the couple on a regular cadence;

- Confirming all major financial decisions with both spouses before implementation; and

- Maintaining contact information for both partners on file to ensure consistent communication.

If one spouse typically serves as the 'family financial officer', the advisor can still include the quieter partner by copying them on relevant emails or inviting feedback on shared financial decisions. During in-person meetings, advisors can ensure that both individuals have opportunities to express their own perspectives and values, helping the advisor build a more complete vision of the couple's goals, risk preferences, and financial lives.

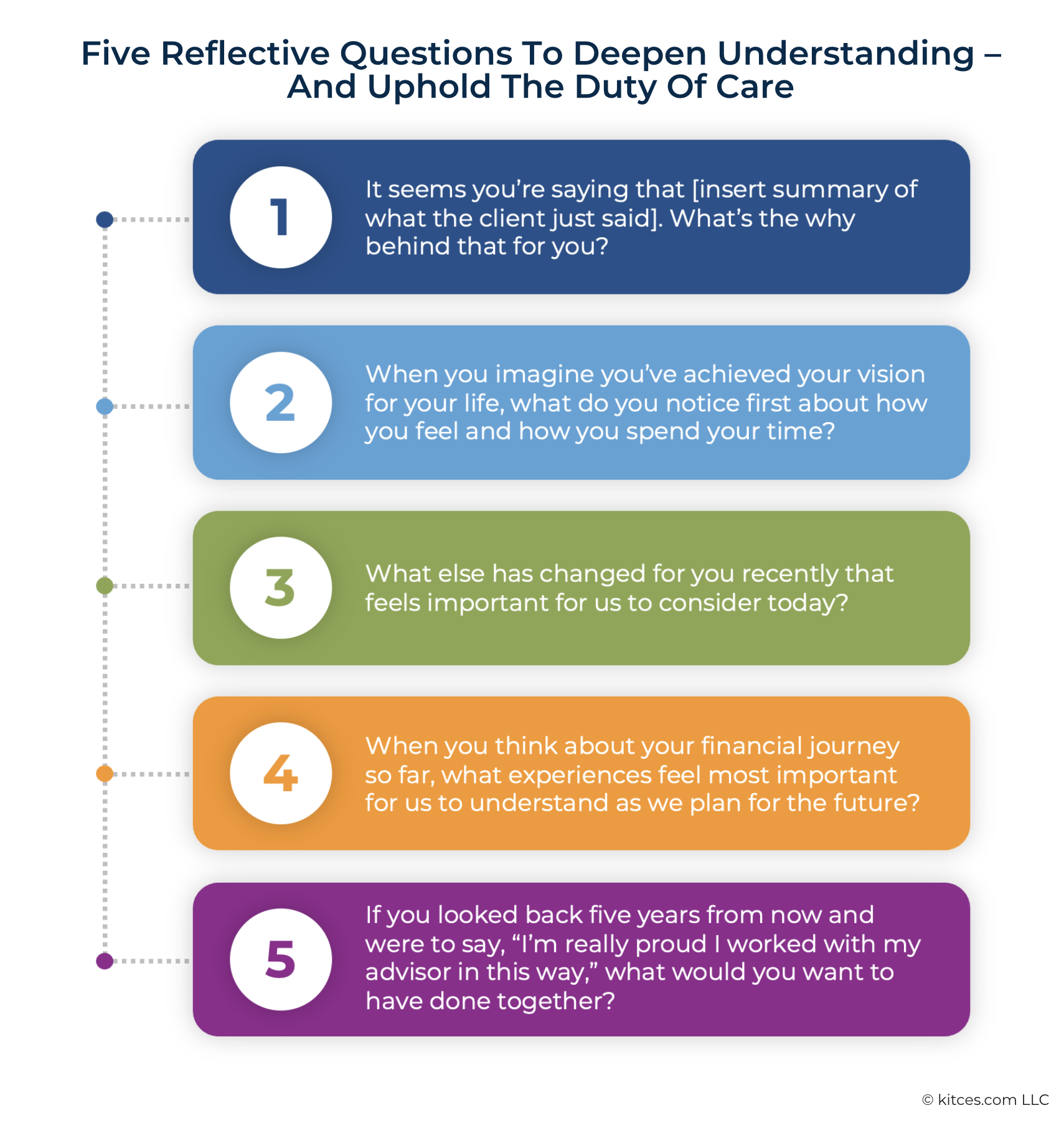

Values-based, open-ended questions can be particularly useful for engaging and getting to know each partner better, which is core to the advisor's duty of care. Reflective questions – such as the classic magic wand prompt ("If you had a magic wand and could change one thing about your financial situation right now, what would you change and why?") – can uncover clients' underlying goals and motivations while also building trust and deepening the client-advisor relationship. Conversations can be extended to explore the meaning of financial success for each partner, times from their past that influenced how they see money today, or reactions to past financial market events.

These conversations may encourage engagement with both partners by creating a comfortable environment for exploring their values, personalities, and risk tolerance, without relying solely on formal data collection methods that may intimidate a spouse who feels less confident about their financial knowledge. Ensuring that both partners have space to speak helps the advisor gather the information needed to meet the duty of care, even when one is quieter or less outgoing. Importantly, a quieter spouse is not necessarily disengaged; they may simply be introverted, less confident in financial discussions, or still developing trust in the advisor.

Demonstrate Fiduciary Behavior Through Documentation

While acting in the client's best interest is the guiding principle of fiduciary duty, maintaining thorough documentation is how that principle is demonstrated. Getting in the habit of keeping detailed notes and records is not just a compliance requirement but an ethical safeguard as well, showing that the advisor acted with loyalty, prudence, and diligence. This is especially important when relationships are strained. During difficult times when emotions are running high – such as divorce – even minor misunderstandings can quickly escalate into major disputes, and financial advisors may become the target of misplaced frustration.

Detailed records on any scope changes to the engagement, along with the effective dates of such changes, can be valuable when working with clients during a divorce. Good documentation can prove intent and provide a history of how an advisor has interacted with the clients. It can also show the information shared with each spouse over time and offer clarity on how decisions were made in the past, when neither the advisor nor the client may remember the details of specific situations.

With modern tools like AI notetakers, recording meeting notes and sharing conversation summaries with clients have never been easier. However, these tools may not always capture the advisor's reasoning behind recommendations, so supporting documentation and advisor notes on significant client matters remain essential.

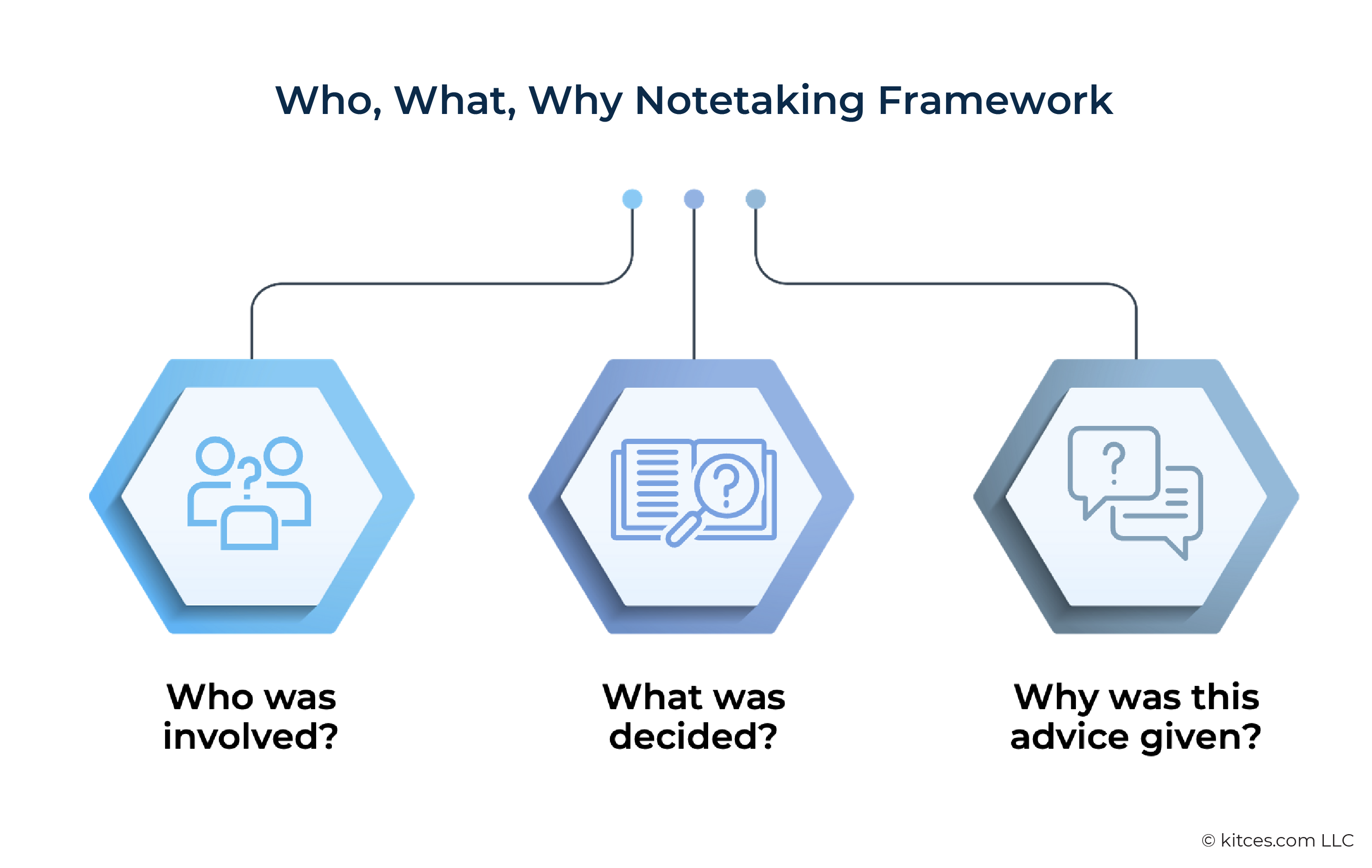

A simple "Who, What, Why" framework can serve as a guide when deciding what to document and auditing notes for completeness:

- Who was involved?

- What was decided?

- Why was this advice given?

Each of these elements can ensure detailed records of the advice given and actions taken, along with the process for delivering and executing recommendations. Centralizing records in a Client Relationship Management (CRM) system ensures consistent, organized documentation while providing continuity and accessibility for all team members, which is essential, as the best notes are useless if they can't be found when needed.

Preparing In Advance For Marital Status Changes

Although the dissolution of a client's marriage can be a jarring experience for both the client and the advisor, divorce is a common life event. Pew Research Center reported that, in 2023, more than 1.8 million Americans divorced. While not as fun to discuss as milestones like retirement or welcoming a new child, divorce is still a major transition, which advisors can prepare for in advance.

CFP Board's Divorce Guide recommends including advance agreement provisions in the engagement letter outlining how the advisor will serve married clients if a conflict of interest arises due to divorce. These provisions can define the limits of services provided by the advisor, specify how representation will change if a joint engagement ends, and clarify which party – if either – the advisor may continue to serve.

Example Language To Clarify Expectations In Joint Client Agreements

Below are examples of engagement-letter language that can help set expectations for how a joint relationship will be managed and proactively address issues that may arise due to divorce. Engagement letters vary by firm and scope, but these examples can be tailored to the relevant sections in the engagement letter, such as the financial planning process, implementation or monitoring of accounts, disclosure of material conflicts of interest, engagement timing and termination, and client responsibilities.

The goal isn't to draw undue attention to the possibility of a breakup, but rather to ensure clients understand how the advisor will operate if the situation arises – and what responsibilities each client holds in return.

Information Disclosure

We will rely on information provided by each client and assume that all information shared with us is complete and accurate. Both clients agree that all material financial information will be shared with one another and with [Firm Name] for the purpose of providing advice. If either client requests that certain information be kept confidential from the other, we may, at our discretion, suspend or terminate the engagement.

Client Communication

All significant communications, meeting summaries, and deliverables will be provided to both clients. We request that both clients attend review meetings or, if one client is unable to attend, that they review meeting notes and provide acknowledgment of decisions within [X days].

Authority to Act

Neither client may authorize transactions, transfers, or account changes on jointly managed accounts without the other client's written consent, unless otherwise specified in account documentation. We will confirm instructions in writing before taking any action that materially affects jointly held assets.

Marital Status Changes

In the event that you separate, divorce, or otherwise experience a material change in marital status, you agree to notify us promptly. Upon notification, our default policy will be to suspend or terminate the joint engagement and cease providing advice to either party until we receive written direction regarding future representation. We may, at our discretion, enter into a new engagement with one or both clients after obtaining informed consent and completing a conflict-of-interest review.

Client Confidentiality

We will maintain confidentiality as required under Federal and state law and professional standards. After termination of a joint engagement, we will not disclose information provided during the joint relationship to either party without written consent from both clients or as required by law.

Engagement Termination

Either client may terminate this agreement at any time by written notice. Upon termination, we will cease providing joint services and confirm the termination in writing to both clients. Fees will be prorated based on work completed to date.

Divorce can create upheaval not only in the couple's relationship but also in the advisor-client relationship, presenting new ethical challenges, such as protecting privacy between spouses, restructuring or terminating client relationships, and avoiding harm even when the spouses' interests may no longer be aligned. Where marital conflict puts a spotlight on the need for ethical clarity, advisors must acknowledge that working with couples as clients, even in the best of times, requires intentionality to ensure they are adequately meeting their fiduciary duty, obtaining informed consent, and maintaining client confidentiality.

Establishing clear structures – clarifying who the client is, engaging both partners in joint engagements, documenting actions, decisions, and the process of serving the client, and evaluating firm processes for addressing marital status changes – can help advisors uphold fiduciary duty, protect client trust, and minimize the risk of regulatory or disciplinary actions.