Executive Summary

Selecting a trustee is a pivotal decision in the creation of an estate plan. Trustees hold title to assets in the trust and can often have great discretion over how trust assets are managed and distributed. No single person is more responsible for ensuring the trust creator's wishes are carried out. And yet, many trust creators give little thought to whom they will designate as a trustee, often defaulting to a close relationship, like a family member. But with potentially complex and delicate family dynamics at play, it can be hard for a family member trustee to make the right decision on the trust's behalf – often to the detriment of both the trust beneficiaries (whose interests might not be best served by a conflicted or easily persuadable trustee) and the trustee themselves (for whom the burden of making all of the decisions on behalf of the trust can be extremely stressful).

As a result, it's often a safer alternative to designate a professional "corporate" trustee instead of naming an individual family member. As a neutral third party, a corporate trustee is often better equipped to manage the sometimes-conflicting interests of trust beneficiaries and make objective decisions on behalf of the trust. Additionally, as a professional institution, a corporate trustee has the experience and knowledge to navigate the legal complexities of trust administration and oversight, which an individual or family member may lack. And while the death, incapacity, or resignation of an individual trustee can throw even more confusion and uncertainty into the situation, a corporate trustee, at least in theory, offers continuity for the entire existence of the trust.

Despite the potential benefits of naming a corporate trustee, financial advisors are sometimes reluctant to recommend their utilization to clients. That's because corporate trustees are typically found in the trust departments of banks and other financial institutions, which often aim (and sometimes outright require) to not only serve as trustee but also as the custodian and investment manager of the trust assets. Which means recommending a client to name a corporate trustee could invite the risk of that trustee wresting away the client relationship from the advisor.

However, not all third-party trustees seek to hold and manage trust assets. A small number of corporate trustees specifically hold themselves out as being "advisor-friendly" and focus solely on the administration of trust assets, allowing them to partner with the advisor (who can continue to manage the trust's investments) rather than competing with them. Additionally, there's a whole ecosystem of smaller boutique professional trustees who work closely with (or sometimes are the same as) the attorneys who draft the original documents and can offer highly personalized and knowledgeable services to trusts with specific or complex needs – again, with no fear that the trustee will seek to usurp the advisor's role of investment manager.

In addition to the selection of the trustee, the trust language itself can affect the continuity of the advisor's relationship with the trust after the death of the client who created it. In a traditional "delegated" trust, the trustee has the sole authority to delegate investment functions – which means they can, at least in theory, name a different investment advisor or impose restrictions that materially alter or disrupt the advisor's investment management process. But when the trust is a "directed" trust, the trust document itself specifies who has authority over investment decisions, rather than leaving it up to the trustee, which may ensure that the advisor's relationship with the trust can endure beyond the death of the original client.

The key point is that advisors can have proactive conversations with clients about trustee selection and the authority that the trust document grants the trustee to make or delegate investment decisions on the trust's behalf. Which in turn enables a discussion to learn more about the client's priorities that can help lead them to an appropriate decision. Because ultimately, it isn't just about the advisor's ability to retain the trust's assets after the client's death – it's about understanding what the client truly wishes to happen once they're gone and no longer able to make decisions on the trust's behalf. Which may not always require the advisor to continue the relationship with the trust and its beneficiaries, but for advisors who do build a deep and lasting client relationship, the client may really want to know how to pass that relationship on to the next generation!

Have you ever sat at a red light with a large "NO TURN ON RED" sign while the driver behind you leans on the horn trying to prompt you to just go? It's jarring, but you know the rules say to stay put. Yet there is a feeling of pressure, where the impatience of someone behind you makes you question whether abiding by the rules is worth the social discomfort. Serving as a family member's trustee can often feel similar.

Not because the law is unclear. Not because the trust document is ambiguous. But, because, in families, interpersonal relationships are complex, and they bring emotional weight to a role that demands impartiality. A trustee often sits at the uncomfortable intersection of duty and emotion. And many of them eventually give in to the emotional/social pressure. Not because they don't take the role seriously, but because being a human being within a fiduciary role is rarely easy.

This tension often leads to divergence from the estate plan's original objectives. Not necessarily in how the documents were drafted, the tax strategy, or the funding of the estate plan, but in the execution of the plan itself. The trustee is expected to be neutral, disciplined, consistent, and primarily driven by the language of the controlling document. Family members are not always the best choice to carry those attributes through to proper execution. Unfortunately, that logical tension can produce significant planning failures.

And yet trustee selection remains one of the most flippant and rushed decisions in the estate planning process. Clients often painfully deliberate on things like distribution ages, but will quickly select a trustee without much thought. "My oldest seems like the fairest choice". These choices can be logical and heartfelt, but they are rarely based on what the role of trustee actually requires.

Being a trustee requires ongoing attention, literacy in legal concepts, diligent accounting, and the ability to say "no" with confidence and clarity (and without apology). For family members, the tasks associated with administering an estate can culminate in emotions that have developed over decades. For advisors, the consequences of poor fiduciary choice are felt in wealth transfer, plan continuity, and the stability of the client relationship across generations.

To avoid such consequences, advisors can proactively broach the subject of trustee selection with their client. By educating themselves – and their clients – about the types of corporate trustees available and the different ways they can work with both beneficiaries and the existing advisor, they can improve the experience of their clients, their clients' heirs, and the advisory firm itself.

Why Trustee Choice Matters – Types of Corporate Trustees

Advisors spend significant time helping clients articulate their intentions, especially regarding their estate plan. They help clients determine who they want to benefit, how assets are managed, and what values they hope will endure. But the execution of that intent depends on who is chosen to enforce those decisions. A trustee is not just a party who manages the assets; they are also a manager of family dynamics during one of the most stressful times a family will endure.

A poorly or flippantly chosen trustee can turn a well-designed plan into conflict and cost. A carefully chosen trustee can turn a complicated plan into something that feels manageable, fair, and aligned with the client's wishes. Advisors who have experienced both know the difference, and they know it intimately.

That's why impartiality, not just competence, is important when selecting a trustee. Families are complex, and trustees must navigate those complexities skillfully. The "most responsible child" who is so often selected by default becomes the reluctant participant in intra-family disputes. Clear language in an estate plan cannot prepare them for the social complexity involved in difficult family wealth decisions.

Advisors are bystanders to these emotional situations, watching the expertly crafted plan unravel because the family member trustee was placed in an almost impossible role. Oftentimes, the advisor becomes collateral damage in the dispute. They may be seen as an obstacle, a co-conspirator, or someone whose relationship to the estate is expendable, as they are solely tied to the original grantor.

Administration Is Where Continuity Dies

Advisors do not always lose intergenerational assets simply because they fail in the planning during life. They also lose assets because of frustration and costly experiences during the estate administration process. Often, the beneficiaries' core impressions of the advisor are not the meetings their parents had, but the experiences that happen after the funeral, when distributions and administration are costly and slow.

Trustee choice can sometimes represent the mechanism through which advisors either retain or lose the next generation. And it's often decided casually, late in the drafting process, without the advisor even present.

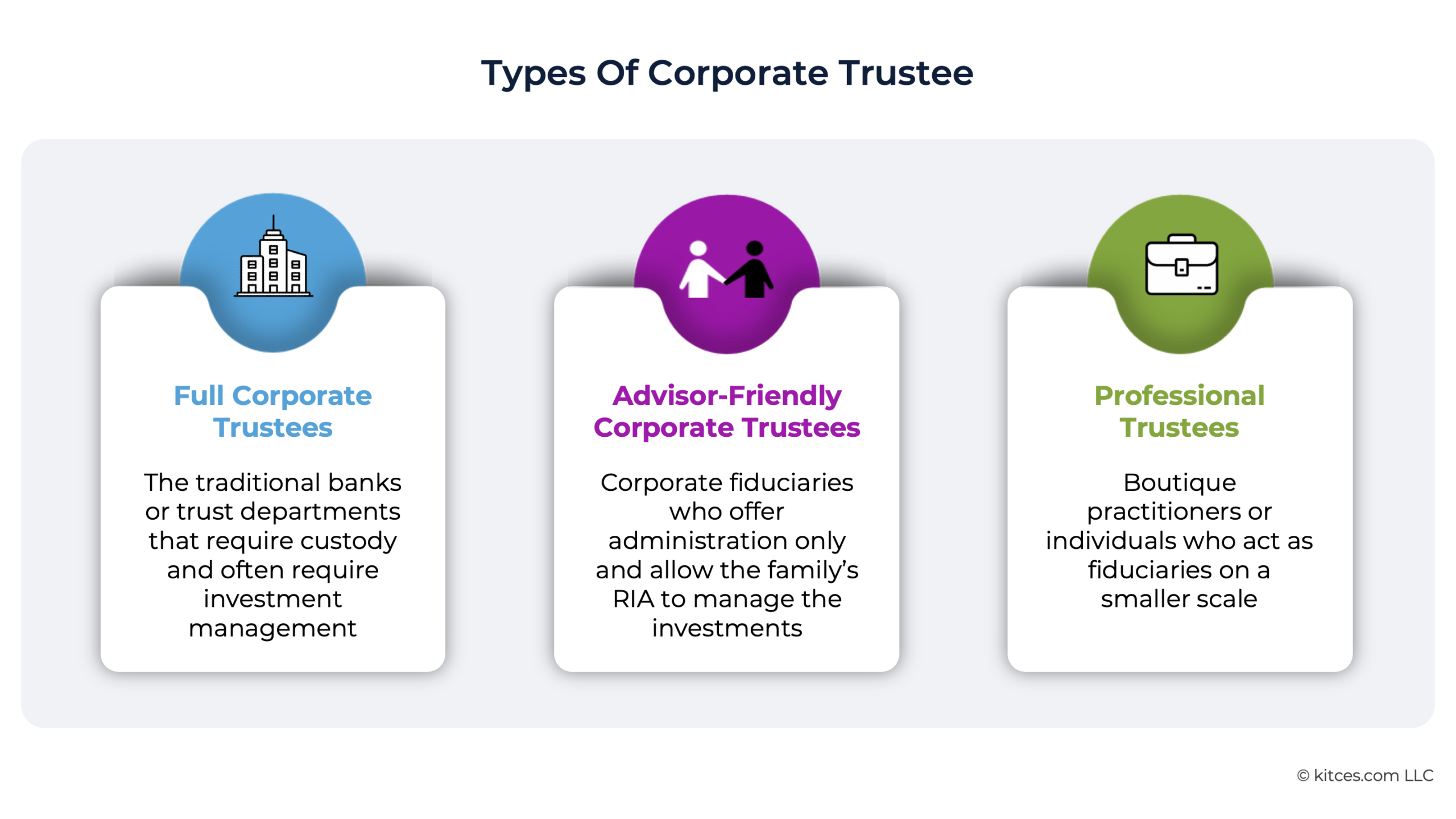

What makes this harder is that "corporate trustee" (in the way that the layman may use it) is not a single category. There are three very different types of corporate trustee, and most clients (and many advisors) do not distinguish between them:

- Full Corporate Trustees: The traditional banks or trust departments that require custody and often require investment management.

- Advisor-Friendly Corporate Trustees: Corporate fiduciaries who offer administration only and allow the family's RIA to manage the investments.

- Professional Trustees: Boutique practitioners or individuals who act as fiduciaries on a smaller scale.

Most clients only know the first type. Many advisors only warn against the first type. But the landscape is far more vast. The advent of advisor-friendly corporate trustees, along with structural innovations that allow RIAs to remain involved without crossing fiduciary boundaries, has altered the way estate planning can support continuity.

Nerd Note:

Many trust instruments do not leave the term "corporate trustee" undefined. Instead, they include an explicit definition that sets objective criteria a fiduciary must meet in order to qualify. A common approach is to require that a corporate trustee be a bank or trust company with trust powers and a minimum level of assets under administration (often stated as a dollar figure such as $500 million or more).

This is where the advisor's voice becomes essential. Clients are highly unlikely to ask attorneys about advisor-friendly trustees because they don't know the option even exists. Attorneys do not always raise the topic because their focus is on drafting the right plan, not necessarily the continuity of existing professional relationships. Without a bridge between these two realities, families may default to familiar names (i.e., family) without understanding the potential long-term consequences.

"Full Corporate Trustees" (i.e., banks, trust departments, and large institutions) play an important role in estate planning. They offer infrastructure, oversight, credibility, and permanence (usually). But they also bring a business model built around asset management rather than trust administration.

Their approach to risk is typically (and understandably) conservative. Their processes are built for standardization and minimal personalization. Their investment philosophy may not align with that of the client's original advisor. The internal bureaucracy may delay decisions during periods when beneficiaries are most anxious. These circumstances are due to the organization's structure, which is not designed for advisor collaboration.

When clients choose a full corporate trustee, they may gain administrative stability but lose investment continuity and personalization. The advisor (who has stewarded the family's wealth story for years) finds themselves suddenly outside the decision loop.

However, choosing a trustee who is neither an individual nor a family member, without going to the full corporate trustee route, is no longer the only option.

Advisor-Friendly Corporate Trustees

An increasingly popular development in the trustee landscape has been the emergence of advisor-friendly corporate trustees. These are fiduciaries who are still corporate, still "permanent", still professionally staffed, but who do not require investment control. Their business model is trust administration, NOT asset management.

The firms that choose this structure partner with advisors rather than replace them. They maintain the infrastructure of a corporate entity while removing the investment competition. They can operate under "delegated" or "directed" trust structures (usually depending on how the trust is drafted). They can also typically communicate with beneficiaries more personally and more nimbly than large institutions.

For advisors, this can be a way to help the client choose a fiduciary that is independent and unemotional, while preserving the continuity of relationships with the client's estate/family. It is a structure that can maintain the original client's long-standing advisor relationship through to their family, even after they are gone.

Professional Trustees

Beyond the more traditional corporate trustee solutions, there is a smaller, but important, group of fiduciaries often referred to as professional trustees. These are boutique trust companies or individual practitioners who intentionally limit the number of trusts they administer in order to provide a high level of personal attention.

Professional trustees are often well-suited for families with sensitive dynamics or situations where trust administration requires judgment, flexibility, and a more hands-on approach. Many professional trustees have long-standing relationships with local estate planning attorneys and a deep familiarity with the intent behind the documents they administer. As a result, they are typically comfortable operating within directed trust structures, collaborating closely with investment advisors while focusing their attention on administration and discretionary decision-making. Another potential benefit is the flexibility to choose the type of estate role they will fill. Some individuals and offices that operate in this manner take on the roles of executor, power of attorney, or even health care agent (roles in which most traditional corporate trustees refuse to serve).

At the same time, professional trustees also tend to operate with certain intentional constraints. Their practices are likely designed to be selective rather than scalable, which means capacity, availability, and long-term succession planning should be evaluated carefully by the advisor and client. These considerations do not necessarily diminish their value, but they do affect the assessment of when to pursue this type of relationship.

Professional trustees are not a universal solution, but they can be an excellent one when the circumstances call for a highly personalized fiduciary relationship. They are a thoughtful option alongside corporate trustees and can play a critical role in the right planning context.

To find such a fiduciary, many state and local bar organizations can be good resources to locate these professionals.

Proactively Leading The Corporate Trustee Conversation

Since clients rarely know there are multiple types of corporate trustees, it is the advisor's responsibility to proactively educate them. Attorneys do not always distinguish between these types during the fiduciary selection conversation. Advisors who are knowledgeable in this area may often default to a simplified warning: "Just be careful if you are naming a corporate trustee, they'll take over the investments". This statement once captured the prevailing sentiment toward corporate trustees, but it no longer reflects reality. Because it is no longer accurate, that sentiment may fail to guide clients toward the structures that best preserve their estate and advisor continuity.

Understanding these distinctions should now be considered core planning knowledge. Trustee choice is not just an administrative question. It is also a relationship and continuity question.

It is also a potentially meaningful ethical question. Advisors who understand how different trustee types interact with investment management, beneficiary communication, and administrative oversight can help clients design a more stable and impartial plan – a plan which helps to reduce conflict, encourage clarity, and honor their client's intent.

Accordingly, the ability to help families understand who should carry out their wishes is one of the most valuable contributions an advisor can make to the estate planning process.

Post-Death Involvement Hinges On Trust Language, Not Just Relationships

Advisors often underestimate how much of their post-death involvement may ultimately hinge not on relationships or goodwill, but on the language that governs decision-making authority once a trust becomes irrevocable.

Advisors may assume that if they have worked with a client and their family for years, managed their portfolio prudently, and earned their trust over time, they will naturally continue in that role for their estate beneficiaries after death. In practice, that assumption will hold only if the trust permits it. Without permission granted by the trust itself, even the most trusted advisor can end up sidelined.

The key is to understand the two main fiduciary frameworks: delegated trusts and directed trusts. Both are legitimate. Both are widely used. But they function very differently depending on whether the trustee is a full corporate trustee, an advisor-friendly corporate trustee, or a professional trustee.

Corporate Trustee Frameworks – Delegated Vs Directed Trusts

Delegated Trusts

Delegated trusts are the default structure in most states, and the format advisors are likely to encounter most frequently. Under a delegated trust structure, the trustee retains fiduciary responsibility for the trust's investments but delegates portfolio management to an advisor. In theory, this preserves advisor involvement while maintaining trustee oversight.

This structure is the most straightforward and common. A trustee may delegate investment functions if they exercise reasonable care in selecting the advisor, establish the scope of the delegation, and monitor the advisor's performance on an ongoing basis. The investment standard the trustee will expect of the advisor is usually defined by statute, such as the Uniform Prudent Investor Act (as it is well understood by courts, regulators, and institutions).

But the experience for an advisor in a delegated trust relationship depends heavily on the trustee itself.

When a full corporate trustee is involved, delegation is often constrained by internal policy and liability risk rather than by law. These institutions are accountable to compliance departments and enterprise risk frameworks that were not designed with outside RIAs in mind. Even when they agree to delegate, they frequently impose conditions that may materially alter the advisor's role.

An advisor may be required to trade only through the institution's custodian, adhere to predefined model portfolios, or operate within investment parameters that differ from the strategy the client followed during life. None of this is inherently improper. It is simply the logical outcome of an institution whose operations and compliance structures are centralized and standardized.

For beneficiaries, this can feel slow and impersonal. For advisors, it can feel like death by a thousand procedural cuts. The relationship technically continues, but the advisor's autonomy is reduced, and the trust begins to feel less like the typical client relationship and more like an institutional account.

By contrast, delegation works very differently when the trustee is an advisor-friendly corporate trustee. These fiduciaries have a business model built for delegation. They do not view outside advisors as exceptions to the rule, but rather as integral partners. Their monitoring obligations still exist, but they are operationalized in ways that support collaboration rather than control.

In these arrangements, advisors usually retain their existing custodians, investment philosophies, and client communication styles. The trustee primarily focuses on administration (i.e., distributions, accounting, tax reporting) while the advisor continues to manage the investments much as they did before.

However, even in its best form, delegation has inherent vulnerabilities, as the advisor serves at the pleasure of the trustee rather than in a truly independent role. Meaning the trustee could technically fire the advisor for any number of reasons (even if it is an unlikely action from a business perspective).

This is why the delegated structure, while common, does not always fully solve the continuity problem. It preserves involvement, but not necessarily the same level of authority.

Directed Trusts

Directed trusts address the vulnerabilities inherent in a delegated trust structure by formally separating fiduciary responsibilities within the trust itself. Instead of the trustee delegating investment authority to the advisor, the trust instrument itself appoints an investment adviser with authority over investment decisions. Since it is a separate and independent role, the trustee is required to follow the advisor's directives when it comes to investment management (except in rare cases of illegality or clear breach of duty).

The increasing popularity of the directed trust structure is a significant step in modern trust law. It reflects a recognition that fiduciary responsibility need not be centralized to one party, but can be allocated to the appropriate professionals best suited to each role.

Nerd Note:

While this article focuses primarily on directed trust structures as a way to preserve the advisor's role in investment management of a trust, modern directed trust statutes allow fiduciary responsibility to be divided across multiple roles, not just investments. In addition to an investment adviser, a trust can designate one or more distribution committees, trust protectors, or administrative trustees, each with authority over a defined function of the trust administration process.

Under a directed trust, the advisor becomes the fiduciary for investment decisions, while the trustee remains the fiduciary for administration. Each party is accountable to its own domain. The separation is intentional, explicit, and legally supported in an increasing number of jurisdictions.

For advisors, a directed trust can allow the investment relationship to essentially survive the client's death without interruption. There is no need to re-engage the client to be hired, no risk of the trust choosing a different advisor (or themselves) to manage the investments, and no requirement to conform to an institution's preferred investment strategy. The advisor continues managing assets under the same philosophy and process that governed the relationship during life.

This continuity creates alignment between an advisor's business interests and a beneficiary's personal needs. It allows advisors to maintain the relationships they've built (and retain assets under management), while offering beneficiaries a sense of stability when so much feels unsettled.

Choosing The Right Trustee Type

Not all trustees are comfortable participating in a directed trust structure. Full corporate trustees are often reluctant to accept directed roles because doing so requires them to relinquish investment control (which is a core component of their business structure and revenue). Some institutions may begrudgingly make an exception to accept directed roles under narrow conditions or with restrictions that dilute the role of the advisor.

By contrast, advisor-friendly corporate and professional trustees are often built for (or even prefer) directed arrangements. Their business models assume that investment authority will reside with someone other than themselves. Their internal processes are designed to support (not resist) the outside advisor.

Why Location May Matter

Another often overlooked aspect of trustee selection (particularly when working with advisor-friendly corporate trustees) is jurisdiction. Many of these trustees operate in states that have favorable income tax treatment and modernized trust laws that favor creditor protection and administrative flexibility. As a result, trustee selection may need to account for the trust situs (the legal location whose laws or statutes govern the trust's administration).

States such as South Dakota, Alaska, Delaware, Nevada, Tennessee, and New Hampshire have developed reputations as trust-friendly jurisdictions by adopting statutes that support directed trusts, limit trustee liability when following lawful directions, extend or eliminate perpetuities periods, and provide stronger creditor protection for beneficiaries. For corporate trustees that focus on administration rather than asset management, operating in these jurisdictions is intentional due to the favorable treatment of their business model.

For clients, this means that naming an advisor-friendly corporate trustee may involve moving the 'location' of the trust. In some cases, this process is straightforward. Trust documents often grant trustees discretionary authority to change situs and governing law without court involvement. In other situations, particularly with older or more restrictive trusts, relocating situs may require beneficiary consent or judicial approval, adding complexity and cost to the process.

These practical considerations can influence trustee selection. Trustees with national charters or multistate operations may be able to administer trusts across multiple favorable jurisdictions, offering flexibility. Others may be limited to a single state, which could require additional steps to place the assets for administration under the trustee.

For advisors, the takeaway is not that every trust should be moved to a so-called 'trust-friendly' state. Rather, it is that jurisdiction is a component of the trustee decision. Understanding how trustee location, governing law, and situs flexibility interact enables advisors to better anticipate issues and help clients select fiduciaries that align not only with their relational goals, but with the legal environment most supportive of their plan.

While creditor-friendly jurisdictions are often intentionally selected by ultra-high-net-worth families concerned with asset protection or dynasty planning, most advisor-friendly corporate trustees are just as comfortable administering more modestly sized trusts. In those cases, trustee selection is often driven more by the desire to engage a specific trustee (based on cost, approach, specialty, etc.) than by potential jurisdictional advantages.

Nerd Note:

When a trustee is selected early enough in the planning process, trust documents can be affirmatively drafted to support the structure. This may include explicit language for directed trust arrangements, clearly defined investment-adviser roles, and broad trustee powers to change governing law or trust situs without court involvement. The selected will often also have preferred language to be inserted into the trust during the drafting process.

Other Considerations Of The Directed Trust Structure

Once the jurisdictional and structural questions are settled, the next step is to understand how directed trusts operate in practice. This includes their cost, administrative process/burdens, and the ethical boundaries associated with the structure.

Fees. Another benefit of a directed trust structure is that it may be less expensive than a traditional bundled trustee arrangement. When a trustee is required to both administer the trust and manage the investments, fees reflect that dual responsibility. By contrast, directed trusts unbundle these roles with the administrative trustee being compensated for their duties, while investment management fees remain with the advisor. Because each party is paid only for the function they perform (and because trustees in directed structures do not price investment liability), the overall cost of trust administration may be lower.

Ethical considerations. What makes directed trusts potentially attractive from an ethical standpoint is that they institutionalize restraint. Each party is constrained by the trust structure. The trustee is unlikely to second-guess investment decisions (as it is not their role to do so). The advisor does not directly participate in distribution decisions because they lack that authority.

This concrete clarity can reduce the likelihood of conflict. It can also reduce the temptation for any one participant to drift outside their defined role under pressure. In families where emotions run high, that structural restraint can be important.

Real-World Application

As a hypothetical example, consider three families with similar wealth, generally well-structured estate plans, and long-standing relationships with their financial advisors.

The Schrute Family names a personal trustee. Dwight, prioritizing loyalty and familiarity, selects his cousin Mose. He sees it as logical, since Mose is his closest family member and knows the beet farm. But once administration begins, Dwight's siblings insert themselves into the process. Trust decisions overlap with personal interests, distribution decisions become uncomfortable, and emotional pressure severely hinders his ability to exercise objective judgment. The advisor remains involved but seems to spend more time navigating family dynamics rather than managing wealth. The plan functions, but its original intent is not effectively honored.

The Scott Family, seeking to avoid family conflict altogether, names a large national bank as trustee. The institution provides a definitive structure and a feeling of stability and certainty. However, this choice requires the institution to take on internal investment management. Assets move, and the advisor's role ends. Administration is competent and orderly, but impersonal. Continuity of the relationship and investment methodology is lost in exchange for institutional control.

The Halpert Family chooses an advisor-friendly corporate trustee and implements a directed trust structure. The trustee is independent and professional but does not require custody of the assets or investment authority. The advisor continues managing investments as before, while the trustee focuses on administration and distributions. For the beneficiaries, the transition feels relatively smooth.

Each family had similar goals. The difference was in the structure. The difference in outcomes has little to do with drafting or investment strategy and largely reflects who was chosen to administer the trust.

How Advisors Can Engage Earlier

By the time advisors feel the consequences of trustee selection, it is usually too late to change it. The client has passed, the trust has become irrevocable, and whatever structure was chosen (intentionally or otherwise) now governs all subsequent interactions.

This is why trustee conversations should happen before documents are signed and created. The goal is not to control the process or supplant the attorney's role, but to help clients understand how abstract choices play out in real life. Advisors who want to preserve continuity must engage earlier in the planning process (not to draft documents or select trustees) but to help clients understand how the trust structure may affect outcomes. When advisors engage early and thoughtfully, trustee selection becomes less about naming a person or institution and more about designing a structure that aligns with the client's goals.

Advisors do not necessarily need to get into the weeds with the client to cite statutes. They need to ask the right questions to determine the client's priorities and help guide them to the appropriate decision:

When you're no longer in control, who do you want to have the authority to keep your investment strategy on course, and how much discretion will they actually have?

If your children disagree, who will be responsible for making the final decision? And are you comfortable that they will be insulated from family pressure?

Do you want the people administering your trust to be the same people managing your investments, or would you prefer those roles to be separated?

If the trustee decides they no longer want to work with your advisor, should that trustee have the ability to make that change unilaterally?

These questions can enlighten the client to focus on structures that support both fiduciary discipline and relationship continuity.

Advisors Rarely Lose Assets Because Of Investment Performance

Advisors rarely lose assets during a generational transition due to underperformance. They lose assets because beneficiaries lack a relationship with the advisor and may also experience the wealth transfer as disjointed, impersonal, and/or confusing. The administration period directly following a client's death is when beneficiaries first experience the plan in action. How smoothly the trustee handles that process can be a key factor in determining whether the family views the experience (and the professionals involved) positively or negatively..

When it comes to a difficult estate administration process, the decedent's advisor can end up 'guilty by association' and blamed for the negative experience and/or outcomes. Advisors may find themselves left out even if they were not involved or had no role in helping the client navigate estate planning decisions. By being involved in the process, the advisor can help the family avoid an overall negative experience.

One reason advisors hesitate to raise trustee issues is fear of overreach. They do not want to appear as though they are recommending specific institutions, encroaching on territory reserved for the attorney, or influencing decisions based on self-interest. These concerns are valid, but manageable.

The most effective advisors frame trustee discussions around function and structure, not names. Instead of suggesting who should serve, they focus on what the role requires and how different structures operate

Finding The Right Trustee

For advisors, the practical takeaway is not that every client should use a directed trust, or that every family should name a corporate trustee. It is that trustee selection and trust structure are no longer abstract legal decisions that can be safely delegated without context. They are strategic planning choices that materially affect how wealth transitions, how families experience administration, and whether advisory relationships survive beyond the first generation.

One of the most effective ways advisors can engage responsibly is by developing a working understanding of the modern trustee landscape, particularly the range of corporate trustees that are willing to serve in administrative or directed roles. These trustees vary meaningfully by size, pricing, jurisdiction, onboarding process, and willingness to accommodate existing advisory relationships. Some operate nationally, others regionally or locally. Some have particular specialties such as special-needs trusts. Increasingly, many large RIAs and broker-dealers have formal referral, white-label, or approved-vendor relationships with these firms, reflecting the growing recognition that trust administration does not need to be bundled with investment management to be effective.

Advisors do not need to recommend a specific trustee to add value. But advisors who can explain the categories, the tradeoffs, costs, and how different fiduciary structures function in practice are far better positioned to guide families toward outcomes that align with their goals.

Continuity During The Great Wealth Transfer

Trustee selection matters even more in the context of the Great Wealth Transfer. Upwards of 90% of heirs choose to leave their benefactor's original advisor when it comes to intergenerational transfers. Which means that advisors have an opportunity not only to reassure clients that their wealth will be passed on to the next generation in the most tax-efficient way possible, but also to engage the entire family and show their value as a trusted advisor who would be the best resource to help the family's next generation continue the legacy of preserving family wealth.

Directed trust structures can be a valuable tool for preserving the continuity of the investment relationship and reinforcing the planning values established and utilized during the client's lifetime.

Clients will always feel pressure. There will always be 'difficult' beneficiaries. Disagreements are guaranteed. The question is whether the estate plan is designed to deal with those pressures or whether it leaves a person stuck at the proverbial 'red light', trying to decide whether to turn under pressure despite the sign clearly telling them not to.

Good estate planning (and proper trustee selection) does not eliminate the car horn from honking behind you, but it can make it less vexing.

When advisors help clients design trustee structures that reinforce restraint, clarify authority, and preserve continuity, they are not just protecting assets. They are protecting relationships across families, professionals, and generations.

This content is for general information only and is not intended to provide specific legal, tax, or other professional advice.