Executive Summary

Given that the pace of technological change is often swift, regulatory bodies often struggle to keep regulations up to date amidst a rapidly changing landscape. In the past couple years, the rapid increase in investment adviser use of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-powered tools has presented a challenge to regulators in attempting to ensure (among other priorities) that client data remains secure while allowing advisers to use this technology to offer better client service. Which has left many open questions as to advisers' responsibilities under relevant regulations when it comes to the use of AI.

In this guest post, Chris Stanley, founder of Beach Street Legal LLC, discusses how the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) appears to be viewing AI, how advisers can apply the existing regulatory framework to the use of this technology, including for research, marketing, client meeting note-taking, and portfolio management.

While the SEC under previous Chair Gary Gensler in 2023 proposed a variety of new rules and rule amendments that would have regulated investment advisers' and broker-dealers' use of technologies that "optimize for, predict, guide, forecast, or direct investment-related behaviors or outcomes" (likely intended to target the use of AI without naming it explicitly), these were withdrawn earlier this year, leaving advisers to look to the existing regulatory framework (e.g., the Advisers Act, the rules thereunder, and Regulation S-P) as well as statements made by SEC officials for guidance when it comes to using AI tools appropriately.

The concept of 'trust but verify' is applicable in several areas when it comes to adviser use of AI. For instance, advisers using AI tools for conducting research will likely want to verify the accuracy of AI-generated output (as these tools continue to experience hallucinations and misinterpretations). Similarly, advisers using AI in marketing (or touting their use of AI in marketing materials) will want to be aware of both the SEC's "Marketing Rule" and the Advisers Act's anti-fraud prohibitions (as the SEC has issued enforcement actions related to "AI Washing" [i.e., making false claims about an adviser's use of AI]). Additionally, recordkeeping, participant consent, and client privacy and information sharing requirements under the Advisers Act's "Recordkeeping Rule" will be relevant for advisers who use AI-powered notetaking tools.

In this environment, advisers can consider acting proactively to remain in compliance with current regulations and put themselves on good footing for potential changes to the regulatory environment surrounding AI. Such steps, among others, could include surveying staff to understand the firm's current use of AI tools, determining which AI tools and use cases will be permitted (and which ones will not), conducting due diligence on AI tools being used, as well as training and testing staff on these policies.

Ultimately, the key point is that because regulation will invariably lag behind the rapid pace of AI innovation, advisers will, for the moment, have to conform their AI practices as best they can under the existing regulatory framework. Which could allow advisers to take advantage of the capabilities that AI tools provide while maintaining their fiduciary duty to their clients.

It seemed apropos to begin writing an article about artificial intelligence tools by prompting said artificial intelligence tools to write this entire article on my behalf. With Google Gemini, ChatGPT, Perplexity, Claude, and Grok all open in my web browser, I copied what I thought was a rather eloquent prompt into each AI tool and let the GPUs do their thing.

The prompt itself was a bit 'meta', as I first instructed each AI tool to assume the persona and writing style of me – Chris Stanley, the Founder of Beach Street Legal – by ingesting and assessing my previously published articles. I also provided the following parameters:

- The article content should assess the compliance considerations of artificial intelligence tools used by registered investment advisers. More specifically, the article should focus on investment adviser client privacy, confidentiality, and consent obligations, recordkeeping obligations under the SEC's books and records rule (Rule 204-2 under the Advisers Act), disclosure implications about the use of artificial intelligence tools, human oversight and review of the output generated by artificial intelligence tools, appropriate compliance policies and procedures, and recent guidance from the SEC about the use of artificial intelligence.

- The primary registered investment adviser use cases to consider are for general research to aid in the investment advisory and financial planning process, the recording, transcription, note-taking, and summaries of client meetings, reviewing draft email communications, preparing initial marketing content, and assisting an investment adviser in the design and implementation of investment or financial planning advice.

- The intended audience will primarily be investment advisers registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and state securities authorities.

- The article should be a minimum of 4,000 words.

- The tone of the article should be thoroughly researched yet simple to understand

Because I'm constantly trying to see what I can get away with when submitting articles to the Kitces.com editorial team, I also instructed each AI tool to include at least one obscure reference to a country music or hip-hop song from the 90s.

The results were… mixed. On the one hand, each AI tool except Google Gemini generated some pretty awesome 90s hip-hop (and Spiderman?) references:

- Perplexity best summarized the AI recordkeeping challenges faced by advisers as "Mo' Records, Mo' Problems" (a reference to "Mo Money, Mo Problems" by The Notorious B.I.G.).

- Grok analogized the SEC's Regulation S-P information sharing restrictions and client consent obligations to the song "No Scrubs" by TLC ("No, I don't want your number; No, I don't want to give you mine and; No, I don't want to meet you nowhere; No, don't want none of your time").

- Claude produced the best opening hook, complete with the AI-requisite em dash: "The artificial intelligence revolution has arrived in financial services with all the subtlety of a Notorious B.I.G. track dropping in 1994—impossible to ignore and fundamentally changing the game forever".

- ChatGPT inexplicably added this Spiderman-derived banger: "With great algorithmic power comes great regulatory responsibility".

On the other hand, the AI-generated 'articles' were all too general and bereft of nuance to serve as anything I would feel comfortable putting under my byline. Ultimately, I concluded that I'd have to write this article myself, the 'old-fashioned' way. Hrumph.

The Current Regulatory State Of Affairs

If Rule 204-2 under the Advisers Act (the "Recordkeeping Rule") is any indication, the gap between the existing investment advisory regulatory framework and technological innovation has never been wider. The most striking evidence of this gap can be found in the current Recordkeeping Rule, which hilariously still references "microfilm" and "microfiche" as examples of how advisers can store their required books and records (and ostensibly produce them to the SEC in the event of an examination). To quote the Recordkeeping Rule itself, "The records required to be maintained and preserved pursuant to this part may be maintained and preserved for the required time by an investment adviser on: (i) Micrographic media, including microfilm, microfiche, or any similar medium…".

Microfilm was invented in the 1800s.

While admittedly an extreme (but real) example, the point stands that the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 (the "Advisers Act") and the rules thereunder were not originally conceived – and have not been substantively updated – to account for the nascent yet rapidly evolving uses of AI by advisers.

What follows is a brief summary of how the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has dipped its toes into the water of AI regulation.

The SEC's Withdrawn Rule: "Conflicts Of Interest Associated With The Use Of Predictive Data Analytics By Broker-Dealers And Investment Advisers"

In 2023, the SEC proposed a variety of new rules and rule amendments under both the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and the Advisers Act that were designed to "eliminate, or neutralize the effect of, certain conflicts of interest associated with broker-dealers' or investment advisers' interactions with investors through these firms' use of technologies that optimize for, predict, guide, forecast, or direct investment-related behaviors or outcomes". While not specifically limited to AI per se, the PDA proposal, as it came to be known, was clearly intended to encompass and prescriptively restrict registrants' use of AI, and painted a skeptical, if not hostile, picture of AI and other "covered technology".

The PDA Proposal was broadly panned by the industry as being overly broad, unworkable, functionally impossible to comply with, and stifling of technological innovation.

Along with a slew of other previously proposed rules and rule amendments originating from prior SEC Chair Gary Gensler's tenure, the PDA Proposal was withdrawn on June 12, 2025. Suffice to say, the originally proposed regulatory framework for AI under the PDA Proposal will not be missed.

The SEC's "AI Washing" Enforcement Actions

In lieu of prescriptive regulation as originally proffered in the PDA Proposal, the SEC has since settled charges with several advisers for "making false and misleading statements about their purported use of artificial intelligence". This practice of exaggerating or falsely touting the use of AI in the delivery of advisory services was coined by the SEC as "AI washing" and rightly pursued as violative of Section 206 anti-fraud provisions of the Advisers Act.

The takeaways from the SEC's AI washing cases are fairly straightforward:

- If an adviser does not actually use AI in the delivery of its advisory services, it should not state that it does. Making a false or misleading statement (whether about AI or otherwise) will constitute a "fraud or deceit" on clients or prospective clients under Section 206(2) of the Advisers Act.

Disseminating any advertisement (including, e.g., a public website) that i) includes any untrue statement of material fact; ii) omits to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statement made, in the light of the circumstances under which it was made, not misleading; or iii) includes information that would reasonably be likely to cause an untrue or misleading implication or inference to be drawn concerning a material fact (whether about AI or otherwise) will constitute a violation of Section 206(4) of the Advisers Act and Rule 206(4)-1 thereunder.

While the AI washing enforcement actions cited above made for splashy headlines and provided an excuse for yet more content to be published on the topic of AI, they did not materially change the regulatory state of affairs for AI. Nearly identical enforcement actions could have been brought if the advisers in question had falsely claimed to use a Ouija board to make winning stock picks.

AI-related or not, advisers simply can't make false and misleading claims.

The SEC's 2025 Exam Priorities

In October 2024, the SEC published its examination priorities for the 2025 fiscal year. In addition to perennial priorities like fiduciary duty and standards of conduct adherence, cybersecurity, and compliance program effectiveness, the SEC also signaled an interest in the use of AI: "If advisers integrate artificial intelligence (AI) into advisory operations, including portfolio management, trading, marketing, and compliance, an examination may look in-depth at compliance policies and procedures as well as disclosures to investors related to these areas".

The ostensible focus, perhaps not surprisingly, is on compliance policies and procedures and investor disclosure – items that often serve as the foundational lens through which examinations are conducted. Unfortunately, there was no accompanying description of exactly what policies and procedures or disclosures should be contemplated, but this is often the case with the principles-based regulatory framework of the Advisers Act and the rules thereunder.

Though I personally haven't encountered any AI-specific inquiries from SEC examiners among our clientele, I suspect it will only be a matter of time before such inquiries are more routinely woven into the exam process.

The SEC Roundtable On Artificial Intelligence In The Financial Industry

In March 2025, the SEC hosted a roundtable discussion on AI in the financial services industry that included both SEC Staff and various industry panelists. Panel discussions centered on AI's i) benefits, costs, and uses; ii) fraud, authentication, and cybersecurity; iii) governance and risk management; and iv) what's next/future trends.

The entire roundtable was recorded and is publicly available in a series of five YouTube videos. Because I have not recently found myself in need of a cure for insomnia, I have not yet watched all five hours of the YouTube videos in their entirety. However, I did ask a few AI tools to summarize the videos and accompanying transcripts to generate a list of the salient takeaways. Edited versions of the results are set forth below:

- Many sophisticated AI models operate as 'black boxes', and even their developers cannot fully articulate the reasoning behind a specific output. This poses a significant challenge to an adviser's fiduciary duty to provide advice with a reasonable basis. Be on the lookout for AI-generated output that favors the investment adviser's commercial interests rather than a client's best interest, and mitigate any generated biases.

- Remain diligent with respect to AI-enabled cybersecurity risks. Consider layered authentication (risk-based multi-factor authentication), transaction-level anomaly detection, vendor diligence on biometric/voice solutions, and incident response playbooks that contemplate AI-enabled attacks.

- There are no AI-specific rules currently on the books. As such, the existing regulatory framework and fiduciary duties already applicable to advisers continue to apply to the use of AI. More specifically:

- The duties of care and loyalty are paramount. An adviser cannot defer its fiduciary responsibility to an algorithm. An adviser must understand the AI tool's function, its limitations, and ensure its outputs are in the client's best interest.

- Any claims made in advertisements about an adviser's AI capabilities must be substantiated and not misleading. Exaggerating the power or accuracy of an AI tool (i.e., AI washing – as described above) will continue to be a key enforcement focus. Avoid puffery.

- Advisers must have policies and procedures reasonably designed to prevent violations of the Advisers Act. This means AI-related risks must be identified, and compliance programs must be updated to manage them. Inventory AI systems and clearly define use cases. Ensure 'human-in-the-loop' oversight is threaded into AI adoption. Retain documentation to evidence the testing of these policies and procedures.

- The amended version of Regulation S-P will now require incident response programs and client notification as soon as practicable (but at least within 30 days) when sensitive customer info was – or likely was – accessed or used without authorization. It also expands the definition of "customer information" and adds various recordkeeping requirements. This directly affects AI/data workflows and third-party tools.

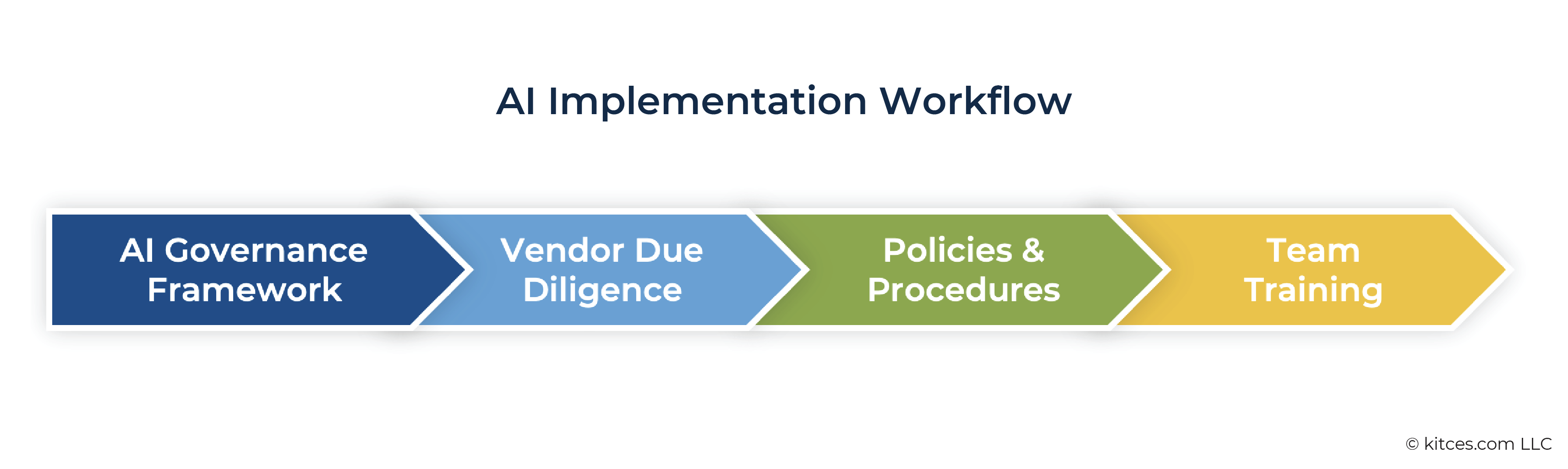

- When adopting AI, advisers should:

- Establish a formal AI governance framework. Do not treat AI as a simple software upgrade. For larger advisers with multiple departments and a formalized governance structure, consider creating a cross-functional committee (comprising legal, compliance, IT, and investment professionals) to oversee AI adoption, testing, and implementation.

- Conduct rigorous vendor due diligence. If using an AI tool, an adviser is still responsible for its output. The diligence process must scrutinize the vendor's methodology, data sources, testing procedures, and its approach to managing bias and conflicts. Advisers must understand the tool well enough to satisfy its fiduciary duty.

- Update existing policies and procedures, including with respect to data governance (ensuring the quality, integrity, and security of the data used to train and/or operate AI models), recordkeeping (documenting AI-driven recommendations and the rationale behind them to demonstrate a reasonable basis for investment advice), and model risk management (initial testing, validation, and ongoing monitoring of AI models to ensure they are performing as expected and to detect model drift).

- Focus on training. Ensure that all relevant personnel, from portfolio managers to client-facing staff, are trained on the capabilities and limitations of the AI tools being used, as well as the adviser's policies and procedures governing their use.

- If a regulator or a client asks why a certain recommendation was made, "the model told me so" is an insufficient answer. An adviser must be able to articulate the key factors and assumptions driving an AI tool's conclusions. The SEC will hold advisers accountable for the outcomes produced by their technology.

The SEC Investor Advisory Committee's Disclosure Subcommittee Regarding Digital Engagement Practices

The SEC Investor Advisory Committee traces its roots back to Section 911 of the Dodd-Frank Act. It is tasked with advising the SEC on regulatory priorities, the regulation of securities products, trading strategies, fee structures, the effectiveness of disclosure, and on initiatives to protect investor interests and to promote investor confidence and the integrity of the securities marketplace. It cannot adopt rules or regulations, but it can submit findings and recommendations to the SEC for consideration.

Because this is the government we're talking about, there are, of course, multiple subcommittees within the SEC Investor Advisory Committee. One such subcommittee is the "Disclosure Subcommittee", and it is this Subcommittee that, on November 17, 2023, recommended that the SEC narrow the scope of the since-withdrawn PDA Proposal referenced above. Even the committee specifically tasked with protecting investor interests (and not industry interests) told the SEC to dial back its attempt to prescriptively regulate AI and similar technologies, and to instead focus on AI and predictive data analytics that directly interact with investors – particularly tools that influence investor behavior or deliver recommendations.

The Subcommittee also disfavored the creation of new, duplicative, and potentially confusing rules that overlap with the existing regulatory framework governing an adviser's fiduciary duties of care and loyalty.

Though the Subcommittee's specific recommendations with respect to the PDA Proposal are now moot (since the PDA Proposal was withdrawn as noted above), its perspective will likely still inform future potential rulemaking with respect to AI.

Prior SEC Chair Gary Gensler's "Systemic Risk In Artificial Intelligence" Vs Current SEC Chair Paul Atkins' AI Task Force

Gary Gensler served as the Chair of the SEC from April 2021 to January 2025. He was succeeded by current SEC Chairman Paul Atkins, who previously served as an SEC Commissioner from August 2002 to August 2008.

I think it's fair to characterize prior Chair Gensler's view of AI as… 'concerned'. Two public statements in particular – a YouTube video entitled "Systemic Risk in Artificial Intelligence" and a speech before the National Press Club – both suggested that AI had the potential to introduce "systemic risk" into US financial markets, "heighten financial fragility," "encourage monocultures," and "exacerbate the inherent network interconnectedness of the global financial system". Such sentiments signaled a global, macro-level concern about AI, and all but set the stage for looming regulation of AI by the SEC.

With the benefit of 20/20 hindsight, the speech before the National Press Club now seems like a fairly clear preemptive justification for the PDA Proposal discussed above: "The challenges to financial stability that AI may pose in the future will require a lot of new thinking" (emphasis mine). At least to me, "new thinking" = new rules. I don't think it's a coincidence that the PDA Proposal was issued less than two weeks after the National Press Club speech.

Not only was the PDA Proposal withdrawn less than two months after current SEC Chairman Atkins was sworn in, but the SEC itself created an internal task force to adopt AI within the SEC for enhanced innovation and efficiency less than two months thereafter: "The AI Task Force will empower staff across the SEC with AI-enabled tools and systems to responsibly augment the staff's capacity, accelerate innovation, and enhance efficiency and accuracy".

From prescriptive and arguably hostile regulation of AI, the SEC has at least initially reversed course to itself embrace AI within its own operations. The one-eighty isn't entirely unforeseen given President Trump's January 2025 Presidential Action entitled "Removing Barriers to American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence" and its stated policy goal to "sustain and enhance America's global AI dominance," as well as the recently issued "Winning the Race: America's AI Action Plan," but the pace and decisiveness of the regulatory sea change is striking nonetheless.

Applying The Existing Regulatory Framework To AI Use Cases & Tools

At least for now, the existing regulatory framework that advisers have come to know (and love?) still governs the use of AI. The square peg of AI must therefore be fit into the round hole of, e.g., the Advisers Act, the rules thereunder, Regulation S-P, and the general fiduciary duties of care and loyalty owed by all advisers to their clients. The upshot of the square peg/round hole juxtaposition is that there is room for interpretation regarding how advisers should compliantly integrate AI tools into their practices. What follows is my interpretation of best practices, prohibitions, and SEC examiner expectations with respect to the most common adviser uses of AI that I've encountered to date.

Research

The entry point into the world of AI for most advisers is likely the most innocuous: conducting online research regarding investment, financial planning, or related topics to inform and educate advisory personnel. Google's search tool, for example, now includes a selectable 'AI Mode' option when conducting searches and generates an 'AI Overview' of search results by default – even when AI Mode is not selected.

Whether or not advisers avail themselves of AI Mode or the AI Overview in the course of general research, the takeaway is the same: trust but verify. Much like advisers (hopefully) review and verify source material to inform and educate themselves before relying on non-AI-generated search results in the course of rendering advice or recommendations to clients, advisers should do the same with respect to AI-generated search results. AI tools are still prone to hallucinations or misinterpretations, and unchecked reliance invites the conveyance of inaccurate advice and recommendations to clients. As a reminder, the SEC will hold advisers accountable for the advice and recommendations they render – hallucinated or not.

Advisers should tread more carefully if an AI tool is to be used for client-specific research, lest the adviser inadvertently include client nonpublic personal information as part of a prompt that will ultimately be used by the AI tool for model training purposes, third-party information sharing, or other purposes beyond the information sharing practices an adviser has disclosed in its privacy notice or as otherwise governed by Regulation S-P.

Advisers should also anonymize or remove any client nonpublic personal information or otherwise identifiable information before entering client-specific queries into a prompt. They should also explore the applicable AI tool's settings, terms of use, and privacy policy to understand what privacy/information sharing settings can be toggled on or off, and how prompts will be retained, used, and shared with third parties.

Ideation, Drafting, And Refinement: Marketing Content And Emails

Ideation, initial draft creation, and refinement of marketing content and client communications are all natural candidates for AI tools, as an adviser can engage an AI tool for theoretically infinite iterations of blog articles, social media posts, video scripts, emails, and newsletters, to name just a few use cases. Again, the key is to trust but verify any AI-generated or AI-assisted content before disseminating it to clients or the general public. This is especially the case with content or communications upon which a recipient may rely or is otherwise actionable by an investor.

If a piece of content constitutes an "advertisement" pursuant to Rule 206(4)-1 under the Advisers Act (the "Marketing Rule"), it will be subject to the Marketing Rule's general prohibitions against making untrue, misleading, or unsubstantiable statements, omitting material facts, or not otherwise being fair or balanced (among other requirements and prohibitions).

Advertisements and other communications are also subject to the general anti-fraud provisions found in Section 206 of the Advisers Act, which prohibit an adviser from defrauding any client or prospective client, engaging in any transaction, practice, or course of business which operates as a fraud or deceit upon any client or prospective client, or otherwise engaging in any act, practice, or course of business which is fraudulent, deceptive, or manipulative. Intent or "scienter" (for my legal friends) is not necessarily required, and unintended or otherwise negligent commissions of fraud, deceit, deception, or manipulation can still trigger liability under the Advisers Act's anti-fraud prohibitions.

Much like the SEC's AI washing enforcement actions cited violations of both the Marketing Rule and the anti-fraud provisions of the Advisers Act, the SEC would likely take similar issue with an investment adviser that publishes content advocating for an investment or financial planning strategy based on incorrect or hallucinated source material derived from an AI tool.

The overlay of an AI tool with an email provider can be particularly thorny, even if an investment adviser simply uses an integrated AI tool to help draft or refine client communications. Email is rarely, if ever, an appropriate mechanism to transmit nonpublic, sensitive information (such as a Social Security Number, date of birth, account number, etc.), but such practices would be particularly challenging to justify if such email provider is integrated into an AI tool that feeds email content into its model or shares it with third parties.

Client Meeting Recording, Transcription, And/Or Summarization

Perhaps the most common AI use case I've encountered has been with respect to the recording, transcription, and/or summarization of virtual meetings with clients. Such tools typically join as a participant through the adviser's virtual meeting software or otherwise run in the background to capture the video and/or audio content of virtual meetings, transcribe and/or summarize such content in written form, and then host the recording, transcription, and/or summary in the tool's cloud environment for the adviser to access as needed. This can be particularly useful for capturing adviser and client action items, evidencing the verbal transmission of information or disclosures, and generally memorializing the discussion for future reference.

These recording, transcription, and summarization capabilities trigger a number of compliance considerations.

Recordkeeping

Subpart (a)(7) of the Recordkeeping Rule requires advisers to maintain written communications received and sent relating to:

- Any recommendation made or proposed to be made, or advice given or proposed to be given;

- Receipt, disbursement, or delivery of funds or securities (money movement matters, e.g.);

- Placing/execution of any order to purchase or sell any security; and

- Performance or rate of return of any managed accounts, portfolios, or securities recommendations, as well as certain predecessor performance information.

In other words, if an adviser sends or receives any written communication relating to any of the four topics bulleted above (whether or not to or from a client or internally among firm personnel), the adviser should maintain such communications for at least 5 years from the end of the fiscal year in which such communication was sent or received (even if in microfilm or microfiche).

Technically speaking, an audio/video-only recording of a client meeting that is not also accompanied by a written transcript or summary does not necessarily constitute a "written" communication in the literal sense of the term and is thus likely not subject to the four corners of subpart (a)(7) of the Recordkeeping Rule (though if such audio/video recording is deemed to meet the definition of an "advertisement," subpart (a)(11)(i) of the Recordkeeping Rule would apply).

Furthermore, if a recording, transcription, and/or summary of a virtual client meeting is captured by an AI tool but simply hosted on the tool's cloud environment without also being transmitted to the adviser, client, or other third-party in writing (via email follow-up, e.g.), it is reasonable to conclude that such recording, transcription, and/or summary has not risen to the level of a "written communication" that has been "received" or "sent" by the adviser – and is therefore also likely not subject to the four corners of subpart (a)(7) of the Recordkeeping Rule.

If a recording, transcription, and/or summary of a virtual client meeting is communicated to the meeting attendees via email, chat, text message, or other written means of communication, the recordkeeping carve-outs described above are out the window. Presumably, however, advisers are already capturing and archiving their emails, chats, text messages, and other written means of communications subject to subpart (a)(7) of the Recordkeeping Rule, and thus any recordings, transcriptions, and/or summaries transmitted through such channels should already be captured and archived. You are capturing and archiving your written communications… right?

It is also worth noting that the Recordkeeping Rule requires an adviser's records to be "true" and "accurate". To the extent that an AI-generated recording, transcript, and/or summary is subject to the Recordkeeping Rule, advisers are under an obligation to ensure such records do not contain hallucinations or otherwise misconstrued content, lest the record be deemed to be false or inaccurate and therefore technically violative of the Recordkeeping Rule.

Advisers should thus consider having a human review AI-generated recordings, transcripts, and/or summaries that are subject to the Recordkeeping Rule (or that will otherwise be relied upon by the adviser, a client, or a third-party) to ensure accuracy. If a human review of such AI-generated content is impracticable due to resource constraints, the adviser should carefully reconsider whether it is prudent to be generating such AI-generated content in the first place.

Notwithstanding the potential for needle-threading the Recordkeeping Rule, advisers may very justifiably want to consider adopting policies and procedures that require retention of audio/video-only AI recordings and/or non-communicated recordings, transcriptions, and summaries for risk mitigation or future complaint defense purposes. The specific risk appetite of each adviser and the technological capabilities (and limitations) of the particular AI tool to be used should inform this decision-making.

Participant Consent

If a virtual meeting is to be recorded, transcribed, and/or summarized (using an AI tool or otherwise), both Federal and state law afford certain participant consent rights. Whereas Federal law and the laws of most states generally only require the consent of one party to a recorded virtual meeting (e.g., the adviser hosting the virtual meeting), certain states require the consent of all parties.

These 'all-party' consent states are effectively the reason why virtual meeting software and AI recording, transcription, and/or summary tools have some sort of alert, pop-up, banner, click-through, or other mechanism to inform all attendees accordingly and afford them the opportunity to consent and proceed with the meeting or instead exit the meeting.

Advisers should ensure that such consent mechanisms are functioning properly or enabled if not already enabled by default.

Client Privacy And Information Sharing

Not to beat a dead horse, but if client nonpublic or otherwise sensitive information is captured by an AI tool as part of a virtual meeting recording, transcription, and/or summary, advisers should fully appreciate what the AI tool will do with such information thereafter (model training, third-party sharing, storage on the AI tool's servers, etc.).

Advisers should also be mindful of not thereafter transmitting a virtual meeting recording, transcription, or summary in which client nonpublic or otherwise sensitive information was captured through an unsecure channel (such as an unencrypted email, e.g.). For example, if a client's full account number or SSN is verbally stated during a virtual meeting, captured and transcribed by an AI tool, and the transcription is then emailed to all virtual meeting participants, the adviser is likely in violation of its cybersecurity policies and procedures and unduly putting the client's nonpublic, sensitive information at risk in the event the adviser or client later suffers from an all-too-common email hacking incident.

Portfolio Or Financial Plan Design And Implementation

Though perhaps less common outside of robo-advisers or tech-forward institutional advisers as of the date of this article, it's only a matter of time before AI tools are more commonly used to design and manage client investment portfolios as well as to design and implement financial plans.

It is this particular AI use case that demands the most Human-In-The-Loop (HITL) oversight to ensure clients aren't being harmed. By way of example only, AI-generated investment or financial planning advice should be carefully screened (by a human) for:

- Alignment with the client's specific financial situation, such as investment objectives, risk tolerance, time horizon, liquidity needs, and – if applicable – investment policy statement;

- Any biases that favor the adviser's proprietary products or services, favor the AI tool's products or services, or otherwise subjugate the client's interests to those of the adviser;

- Trading decisions or recommendations that incur unnecessary transaction costs;

- Mutual fund share class selection that does not reflect the lowest cost share class for which the client is eligible;

- Position liquidation decisions that unnecessarily incur capital gains or other adverse tax consequences; and

- In general, any investment or financial planning decision or recommendation that the adviser cannot substantiate as in the client's best interest.

If an AI tool forms the basis for investment or financial planning advice or is otherwise materially incorporated into the delivery of investment or financial planning advice, there should be corresponding disclosure in the adviser's Form ADV Part 2A brochure. Such disclosure should describe the nature and extent to which AI is used, the inherent limitations of AI, the supervision, control, or HITL mechanisms the adviser has in place, and the risks associated with reliance on an AI tool for investment or financial planning advice. It may also not be a bad idea to include similar disclosure and acknowledgements as part of the adviser's client services agreement as well.

Recommended Action Items

Depending on the nature and extent to which an adviser has adopted or plans to adopt AI into its business, what follows are suggested action items:

- Survey advisory personnel to understand what AI tools, if any, are currently used and how they are being utilized. A team using a variety of disparate AI tools at varying subscription levels when rendering advice to clients and recording client meetings has a significantly different risk profile than advisory personnel simply utilizing native AI-fueled search enhancements for research purposes.

- Determine which AI tools and use cases will be permitted and which ones will not, based on the adviser's business needs, risk tolerance, and oversight capacity. For instance, a firm may narrow its focus to one or a small handful of AI tools that it permits enterprise-wide, rather than allowing advisory personnel to subscribe to and utilize any AI tool they choose individually.

- Perform initial due diligence on applicable AI tools with a specific focus on terms of use, privacy, and information sharing practices, record retention, and model training. For instance, this could entail reviewing the AI tool's terms of use, privacy policy, and other governing documents that apply to the specific plan to which the firm subscribes.

- Adopt written policies and procedures that govern the use of AI. Such policies and procedures can incorporate, e.g., a list of approved AI tools and use cases, CCO pre-approval of any new AI tools or use cases, initial and periodic ongoing due diligence and oversight of AI tools, the type of information that is permitted to be entered into an AI prompt, the records that are to be maintained when using an AI tool, the privacy and security practices that personnel must observe when using an AI tool, HITL requirements, etc. The length and specificity of such policies and procedures will vary based on the extent to which the firm plans to adopt AI into its practices and how AI tools will or will not be used by advisory personnel.

- Train personnel on the new compliance policies and procedures related to AI (with periodic retraining and reminders thereafter). Consider incorporating a section on AI compliance into your regularly scheduled compliance training meetings with the firm's supervised persons (which should ideally occur at least annually). Alternatively, consider sending an 'all-firm' email alert regarding the use of AI tools going forward.

- Periodically test for adherence to the AI policies and procedures and remedy any identified gaps or deficiencies. Such tests can be baked into a firm's compliance calendar; compliance personnel can be on the lookout for unapproved use of AI tools when conducting email reviews, and IT staff can periodically surveil company hardware for AI software that hasn't been vetted.

- Assess whether any additional AI-specific disclosures should be made in the Form ADV Part 2A brochure and/or client services agreement (particularly if AI will be used to form the basis of investment or financial planning advice). Such disclosures should focus on the risks and limitations of the use of AI tools, as well as the controls the firm has adopted to govern the use of AI tools.

- Monitor for future SEC rulemaking, risk alerts, guidance updates, Commissioner speeches, or other regulatory developments specific to AI. Hopefully, we will not need to take our direction from future SEC enforcement actions. Still, if AI emerges as a theme in future SEC enforcement actions, firms should take note and adjust their practices accordingly.

Regulation will invariably lag behind the blistering pace of AI innovation. Future AI-specific and adviser-specific rules may come at some point, but I wouldn't hold my breath in the near term. For the foreseeable future, advisers will simply have to conform their AI practices as best they can to the existing regulatory framework as embodied by the Advisers Act, the rules thereunder, Regulation S-P, and overall fiduciary principles. Yet I think it's fair to conclude that the more an adviser relies on AI – particularly in the context of actionable advice or recommendations to clients – the more an adviser will be scrutinized and held to account.

Perhaps ChatGPT said it best after all: "With great algorithmic power comes great regulatory responsibility".

Leave a Reply