Executive Summary

Welcome everyone! Welcome to the 469th episode of the Financial Advisor Success Podcast!

My guest on today's podcast is David Scranton. David is the CEO of Sound Income Group, an RIA based in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, that oversees approximately $4 billion in assets under management for 10,000 client households.

What's unique about David, though, is how he has built his business by standing out through his strategy of investing client assets in income-producing individual securities to produce a steady stream of income at a time when many advisors have taken a "total return" investment approach and build portfolios using mutual funds and ETFs.

In this episode, we talk in-depth about how David builds portfolios using a combination of what he calls "insured options" (such as bank CDs, government bonds, and fixed index annuities), "non-insured contractual securities" (such as individual bonds and preferred stocks), and "equity-oriented investments" (including business development companies, real estate investment trusts, and high-dividend stocks), why David prefers to invest in individual securities instead of investment funds both to control the exact securities he's investing in and to avoid forced liquidations when investors in a mutual fund sell at once, and how David finds that prospects are often receptive to this approach given the steady cash flow it generates without necessarily eating into principal to create retirement income (which has also led to greater client retention during market downturns).

We also talk about David's four keys for financial advisors to attract clients (which include having a point of differentiation as well as established branding, lead generation, and conversion processes), how David's focus on these keys shifted over time (from an emphasis on lead generation early on in his career to build a steady flow of prospects to branding now that he's leading an advisor enterprise), and how David has leveraged book-writing (with the assistance of professional ghostwriters and publishing firms) to further build his brand and generate greater familiarity with his ideal target clients.

And be certain to listen to the end, where David shares how he implements his investment approach by using two portfolio management tools (for trading and reporting, separately) and offers it to advisors who don't have the capacity to implement this approach themselves, how David was able to overcome his previously overly analytical nature to be able to focus on the bigger picture of running his business, and how David has found that narrowing in on a specialization has ultimately (and perhaps counterintuitively) allowed him to serve more families than he might have taking a more generalist approach.

So, whether you're interested in learning about what it takes to implement an income-based investment strategy, attracting more prospects by showing how your firm is ‘different', or how to build your brand by authoring books, then we hope you enjoy this episode of the Financial Advisor Success podcast, with David Scranton.

Podcast Player:

Resources Featured In This Episode:

David Scranton: Website | LinkedIn

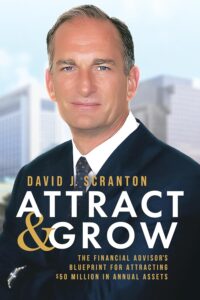

David Scranton: Website | LinkedIn- "Attract & Grow: The Financial Advisor's Blueprint for Attracting $50 Million in Annual Assets" by David Scranton

- "Retirement Income Source: The Ultimate Guide to Eternal Income" by David Scranton

- Forbes Books

- Orion

- SS&C Black Diamond

Are you a successful financial advisor, or do you know of one that would be a great fit for the Financial Advisor Success podcast? Fill out this form to be considered!

Full Transcript:

Michael: Welcome, David Scranton, to the "Financial Advisor Success" Podcast.

David: Well, Michael, thanks for having me.

Michael: I really appreciate you joining us today. And I'm excited to get to delve in and really talk about how we can drive more organic growth by trying to really differentiate what we do with clients, which I find is just becoming increasingly challenging out there in the landscape. Industry average overall is organic growth seems to be slower across the board. There's fewer delegators who have not already found an advisor who will manage their portfolio and do ongoing financial planning. If you've been looking for that for the past 15 years, you probably found it already. And most of the ones who are remaining, if for some reason they don't already have an advisor, seem to be having a lot of trouble telling us apart from what we do and what we offer.

I mean, we all "kind of say" we offer comprehensive planning with our credentials and our years of experience supported by our breadth of capabilities and our above average client service. We all have above average client service. And then consumers basically can't tell us apart. And so, the number one actual Google search for advisors is financial advisor near me, which to me says in the end, they still can't tell us apart. They just flip a coin and pick whoever happens to be most geographically convenient to their home or office.

David: Quite true.

Michael: And I know you have worked hard to differentiate despite or even including focusing on a segment of consumers that many of us pursue, which is kind of the millionaire, the million dollar retiree, not by differentiating who you specialize in, which is retirees, but how you deliver to them with a big focus on retirement income, on income as a theme.

David: That's right.

Michael: And so, I'm excited to talk to you about how you've been able to use income planning, or maybe you have a better label for it, how you've been able to differentiate with income planning as a way to drive organic growth with retirees that so many of us seem to be pursuing at the same time, but you've been able to actually make a differentiator for your firm and attract clients.

Using Income Generation As A Differentiator To Attract And Retain Clients [04:54]

David: Yeah. It all happened by accident. It's not as though I set out to have this as a point of differentiation. I've been in the business for 38 years.

Michael: So, there was not a master plan.

David: No. It's like a lot of things. If you work hard, you do all the right things, eventually, you stumble on things that create quantum leaps in your business. Right It's not a linear growth pattern for most of us. You get these points where you have these quantum leaps. And my biggest one came after 12 years. Because of my 38 years in the business, for the first 12 years, I was like everyone else. I was focusing on total return, really not differentiating between income, interest, and dividends versus capital appreciation. But 12 years into my career, it was in 1999 and I became really concerned about the stock market and that there's likely a tech bubble out there. And I said, well, I need to protect my clients somehow some way. So, what happened was I started to put them in bonds. I started to put them in preferreds and things that were more secure than common stock, and also putting some money in fixed or fixed indexed annuities, and protecting them.

And what happened was, of course, when the bubble did burst with technology stocks, and the market dropped, and then later on the financial crisis, my clients were extremely pleased. And I became known as an income guy where people in my little town in Connecticut said, hey, if you want growth, you can go to Shearson Lehman, you can go to AG Edwards, places that don't even exist anymore.

Michael: There's some irony to that as well.

David: That's right. You want income, go see Scranton. So, here I was. I'm just like a pointy hat CFA, Chartered Financial Analyst, trying to protect my clients, not a marketing guy. In fact, I never took a marketing class in my life. But it was probably the biggest decision in my life that allowed me to start attracting prospective clients and to no longer chase after prospective clients.

Michael: So, I'm fascinated by this evolution that it started with...you were doing the regular thing we all do. We design holistic portfolios. We focus on total return. And the distinction for you basically was not doing that, was putting a pause on that, was going a different direction for that. And I guess I'm all the more struck because it sounds like this was happening for you in the '80s and into the 1990s, which to me was really the heyday of when the whole investing world really started to pile into, well, you can't just focus on the income. You've got to look holistically at the total return because we were getting so much in capital gains.

David: Right. That's exactly what I did for 12 years. And then finally stumbled on to this metamorphosis, which, again, I never thought it would actually be something to help me grow my business. But it was probably the single most valuable decision that I made with the goal of ultimately bringing more people on. Again, attracting instead of chasing prospects.

Michael: Because from the consumer end, the income theme resonated. Is that the transition?

David: Mm-hmm.

Michael: Obviously, there's investment theses around this as well, which I'm sure we're going to get into soon because you're a CFA guy. So, we'll nerd out on that. But it sounds like the shift wasn't the magic of the investment process per se. The shift was clients started to think about you and the firm differently because suddenly you had this position. Right? If you want the growth, go to Lehman or AG Edwards. If you want the income, go to Scranton. And now, suddenly, people are talking about you in a unique and different way.

David: Well, that's right. Like you said, Michael, a few minutes ago, it's hard to differentiate as a financial advisor. If you say, well, we service our clients better, well, that's great, but I only know that once I've been a client for a year or two. If I'm a prospect, I don't know that. Our competitors don't say, oh, we stink at service. Right? Nobody says that.

Michael: Yeah. No one says they don't have good service. So, unfortunately, everyone says they have above average service and clients can't figure out who's telling the truth because we can't literally all have above average service.

David: That's right. That's right. And that was a great point of differentiation. In fact, I actually wrote a book earlier this year for financial advisors, and it's called "Attract & Grow." And I talk about the four secrets to attract and never, ever again have to chase a prospect. And the first of the four secrets is to have a point of differentiation to separate you from your competitors, because if you blend in, well, then by definition, you have to chase. But if you stand out in some way and you get people's attention, then you can grow.

And I've always said, if I had a choice, if I were selling anything, not even...even outside the world of financial products, and I had two choices, I can go into city A, where I was selling something that everybody in city A wanted, but I had 100 competitors, or I can go in city B, where only 10% of the people wanted what I offered, but I had zero competitors. So, I would take B over A any day of the week with that point of differentiation.

And when I started this in 1999, the majority of people didn't want income. Right? Boomers were a lot younger then, Xers were certainly younger then, and they didn't want what I was selling. So, I was selling to a minority, but yet it was such a point of differentiation that I had no competitors in that space. Now, I've gotten to the point where a majority of people actually do want what we offer, and we still really are hard pressed to find true competitors that specialize in income. And you might get that annuity guy, Michael, that has a radio show that says, hey, I'm the safe money guy or something like that. And what do they do? They either use all annuities for everything, as if any one product was the be all and end all, right, which we know isn't true, or they use annuities to drive income, and then the assets under management go for growth for the future. But you'd be hard pressed to find someone who uses both annuities for income and the assets under management for income also. True income, meaning interest and dividends.

So, Michael, I'm not talking about using the 4% withdrawal rule or using the buckets of money strategy and back testing with Monte Carlo analysis. I'm talking about generating real income, interest, and dividends as a renewable resource for retirees.

Michael: And so, we'll get more into the investment approach in a moment. But just from a positioning end, that's helpful to understand the differentiation, which, for you, it's not a we're going to have the secure or guaranteed bucket over here so that we can have the growth bucket over there. The whole point of your process, everything is income-producing across the whole portfolio. That's all the assets. That's not a segmented asset strategy.

David: That is correct. That is correct. And you think about it. You've seen people, husband and wife, they're getting ready to retire. They make, let's say, $250,000 between the two of them. And they have assets, but they're trying to convince you that, in retirement, they want to live off $70,000 a year. You think about that and you say, wait a minute, you weren't saving the other 180 when you were working.

Michael: Yeah. How's this going to work exactly?

David: Yeah. How are you going to make it on $70,000? Well, the reason oftentimes they say that is because that equals their pension and their Social Security benefits. Because somewhere in the back of their mind, they feel as though, gosh, I've spent my entire career putting money in to my retirement savings. And now, to be taking withdrawals, to be withdrawing principle and hoping it grows back, doesn't feel right. It doesn't sit well with them to some level. Now, they may not realize there's another solution. So, in their mind, the only alternative is to not take any withdrawals unless you really, really need the money.

So, by showing people that they can get that renewable resource of interest and dividends and keep their principal intact, all of a sudden, that person starts to think and dream about all the things they really want to do in retirement. And next thing you know, they don't want to live on $70,000 anymore. They want to live off $150,000 or $200,000 because they realize it's not a withdrawal of principal. It's true income.

So, it's a great benefit, which then leads into it being a great referral source, Michael, because now if people can live a better retirement because of what you've shown them, well, now, hopefully, they want to share you with their friends.

David's Four Keys For Attracting (Rather Than Chasing) New Clients [13:05]

Michael: So, I want to delve deeper on the investment end, but you piqued my curiosity. And so, now, I just really have to ask. What are the other three secrets from "Attract & Grow" besides have a point of differentiation to separate you from competitors? I can't stop at one of the four secrets.

David: Well, the second one is branding. Every business in the world knows marketing has two components: lead generation and branding. But financial advisors are so much in the now. Right? Whatever they spend on marketing, they want to get in front of more prospects today. They're not willing to do the long form part of it, which is branding. And branding is essentially educating, educating a consumer why your specialty, why your little niche is better for them. Because we could talk about income, but if you don't brand, they don't really know how I'm different from the guy who's only selling annuities, who says he does income, or the person who's using withdrawal methods or buckets of money strategies. Right? So, branding helps educate them so they understand, oh, now that I saw you and noticed you because you're different, now, I've learned about why that point of differentiation might actually help me.

So, you think about it with big pharma. Big pharma will advertise all these prescription drugs. I don't know if you've ever wondered, but why? I can't go to the pharmacy and get those. Wouldn't they be better off just marketing those drugs to the doctor? Right?

Michael: Right.

David: But no, they want to do grassroots education. So, we know how that drug might help whatever ails us. Right? So, that's the second part, branding. The third part's lead generation, which is where you get people to raise their hand and say, I want to have a one-on-one conversation with you about this. And then, of course, the fourth part is your conversion process, your sales process, because a lot of times I'll see advisors attract. They attract, they attract, they attract. And they get in the sales process, and they do something to unwittingly spook the prospect. And that prospect's gone and never to be seen again. And the advisor never knows how or why that prospect got spooked. So, to truly attract and not chase prospects, you actually have to do all four things successfully. If you get any one of those wrong, you spook the prospect and they're gone.

Michael: So, what are the typical spooking incidents, which I chuckle because we're recording this shortly after Halloween. What are the typical spooking incidents you find where advisors have managed to get a prospect far enough to be in front of them and then end up unwittingly doing something that sabotages the sales process and they go away?

David: Well, sometimes there are specific reasons why an individual does not want to do business with a particular advisor. But I think more than half the time it's really just a general feeling. Something just doesn't feel right. So, it's hard to chase someone and then get them to turn around and start to chase you. Think about it. If I were chasing you down a dark alleyway, yelling and screaming, and you're running from me because you're thinking this guy's crazy, I'm getting out of here. And all of a sudden, I disappeared into a doorway. You have to ask yourself, what are the chances you now are going to turn around and chase after me if you've just been running from me? Slim and none.

So, if you have a lead generation system that's chasing based, not attraction based, direct mail in the old days, chasing based, you're following up on the phone, knocking on doors as some firms still utilize, or cold calling, those are chasing based methodologies. So, if you can use an attraction-based marketing system, now, you're at least starting on the right foot and you're better postured. When you get in front of them one on one, there are so many outdated sales strategies taught from different industries that can spook the prospect. The hard closes, things like that, where all of a sudden, yeah, they were chasing you, they were chasing you, you were successfully attracting them. But now, they feel as though they're getting chased or they're getting backed into a corner, and something just doesn't feel right.

So, that's why I say the sales process is the single place where a lot of people can really struggle. And I have to tell you, if there's a second major metamorphosis in my career, the one being the transition to the income model, the second one is, as a CFA, teaching myself how to sell. After eight years of being broke in financial services and realizing it doesn't matter how many designations you have, if you can't compel somebody to take action, you're not helping anyone, and you're certainly not helping yourself.

Writing A Book (With The Help Of A Ghostwriter) To Build An Advisor's Brand [17:44]

Michael: So, I love the analogy around if I'm chasing you down the alley and suddenly I disappear, are you really going to turn around and start chasing after me when you've just been running from me? No. Once I'm stuck in the chase, for better or worse, I have to keep chasing if I'm ever going to catch. No one turns around and chases back. So, ideally, we're trying to attract them in. I guess, then can you put a finer point on what are the branding or other things we're not doing to make the attraction mechanism actually attract?

David: Writing a book for your typical client. In our case, I wrote the Retirement Income Source to talk about the benefits of income strategies. That's a great tool because you can give it out to prospects, you can do workshops and give it out at workshops. Radio shows are great because you're postured. Most consumers say you don't really realize you're paying for air time, maybe some do, but they feel like, wow, if he's on the radio, he must be the real deal. And then you're offering a copy of your book, and they can get it, and they can read it. And they're learning in a very passive way, but you're directing their education versus...

Think about how people learn today. They go to Google. Google CFP, and they Google things, and then you never know what's going to come up, good or bad or indifferent. Well, if they want to learn, I want to fill their minds with the right type of learning, the learning that's going to educate them why my value proposition is so unique and best benefits them. Radio shows are one great way for branding. Doing commercials on radio or television could be great. Again, being a published author, and even periodically PR things, whether you're being published in an article or whether you publish an article in a magazine or a newspaper or whether you're on television.

Michael: How do I think about this path if I'm not a book writer? It sounds like you have some natural inclination and skill set towards writing and writing a book. Am I stuck if that's not my natural inclination?

David: First of all, let me be clear. I've always had and still have zero inclination toward actually writing my own book. When I went to college, part of how I chose my college was they didn't have any core curriculum.

Michael: No common core means I don't have to get dragged into some of those English and lit classes that I don't want to do.

David: Exactly. I said, if I can just do pure mathematics and science my entire career, I'm a happy camper. So, no, I had no interest. And the other reason for a math degree is because it was the one degree that I could partake in and never have to write a paper. So, when writing the book, the key was to have a good ghostwriter who can copy my voice, but give that person a lot of content of things that I've produced, videos I've produced for clients, and just even stream of consciousness babbling, just talking into recorder and letting this person put the proper content together. Now, it still took a lot of work. I still had to get in there and read it, and course correct, and help them with where there should be edits and where there shouldn't be. But as far as if I had to do all the writing myself, I wouldn't have a book, Michael.

Michael: Interesting. So, you found a ghostwriter, gave them a big, old download of all your knowledge, and thoughts, and philosophy, I guess, around these things because you've at least got radio appearances, TV appearances, other content you've created to give them some framing around it. You gave them all that, and then allowed that to sit and settle as a baseline to get this done.

David: Yes.

Michael: And then they came back...I guess, basically, then they come back with a first draft or similar, and now you're editing a draft. So, you don't have to write it from scratch.

David: That's right.

Michael: You can refine it to your voice, but you don't have to build it from scratch.

David: Editing and course correcting. For me, it was all auditory because I'm a two-finger typer. So, if I had to go in and do edits myself, it would have taken me forever. So, it was just a lot easier to just say, okay, on page six, paragraph two, I think this adjustment needs to be made, and instruct people. And after some back and forth, you end up with a pretty good product. Now, would it potentially have been better...?

Michael: That's interesting. So, you audio narrated or you audio recorded the edits. You're not even typing the edits because you're not a typist.

David: That's right. That's right. It's just easier that way. And I would always think of somebody to work around that method for me, again, to get something out. Would it be a little bit better if I sat down there and wrote it all myself? Would it be a little bit more my voice? Sure. But I know that never would have happened. Now, with AI, I mean, who knows? Maybe I can't actually write my own book right now. But still, I like having that professional copywriter there that can get the theme down pat. And the right person will do a pretty good job at copying your voice.

Michael: So, how did you find the person? I mean, just for some of us, I feel like that's...even if this sounds neat, that's the first blocking point. How do I find the wonderful, magical person that can make this happen?

David: Well, first of all, you could just Google it and find people that are willing to...that you need to interview to see who's... With whom do you click? You have to click with the person. That's extremely important. There's also some companies that will do this as a turnkey service. So, they'll put you in touch with the copywriter, the ghostwriter, and then they'll have the editor, and then have the graphics person. And they'll do all this. It costs you more money to do it that way, but that's okay. And if you get to a point where... Time is more valuable than money. Right? I know at the beginning of a lot of financial advisors' careers, money is more important than time. And even when they're prospecting, they do things that take more time, but are less expensive. But eventually, as you grow, you get to a point where, wait a minute, my time's worth more than money. I'd rather write a check and outsource this so that I can spend time growing my business. And when you get to that point, there are solutions all over the place that can accommodate you.

Michael: So, what was your path of choice? How did you go about getting this done?

David: We've used a couple different paths. Right now, probably the most recent one that we've used is Forbes Books. They'll upcharge you, but they'll do start to finish in the process. And the biggest thing is that the advisor needs to be part of this because I've referred other advisors there. And they sit back and they think literally everything's going to be done for them. And then they get frustrated when it comes out and it's not their voice or it's not what they like to talk about in meetings. So, you do have to invest some time upfront with that person. But these companies, like a Forbes, make it. There are a whole bunch out there, but they make it easier for that advisor. But not so easy that the advisor does nothing. Now, I want to make that clear. Because you won't get a book that you're happy with if you try to take that much of a shortcut.

Michael: And can you give us some context of what this costs? I mean, just set my pricing expectations of what neighborhood or range.

David: If you're looking for a good ghostwriter, you're probably around $15,000 or so just for the ghostwriter for a normal book that takes three to four hours to read, let's say. Now, if you want a service that's going to do everything turnkey, it's probably closer to $40,000. And then prices can go up from there. But that gives you an approximate range. And a lot of these will let you pay in installments because it takes 9 to 12 months from start to finish to get the book. So, it's not like you even have to write a check upfront. You might write a check for $10,000 upfront and then amortize the remaining $30,000 over nine or ten months, something like that.

Michael: So, as you go this path, I feel like the challenge for a lot of us in the advisor world is just figuring out what's actually...what's a good spend, what's a reasonable spend, how do you know if it's working? Whereas you highlighted earlier, it's pretty straightforward to spend on lead gen. I put in X dollars, I got Y prospects, it turned into Z clients because I do my ten through one conversion thing. That's very easy to math and figure out, is this working for me and am I getting an ROI?

David: Right.

Michael: How do you think about it in the context of are you measuring book sales and book revenue? Is there something else? How do you figure out if this is working?

David: There's no really accurate way to do it. Believe me, I'm a math guy. I would love to say that there were, but there just isn't. So, the key is to understand that branding does two things, whether it's a radio show or a book or anything.

Number one, don't expect a lot of leads to come from it. That's why it's not lead generation, it's branding. But what it will do is it'll make other lead generation efforts that much more productive because now, because you're branded, you seem like a safer alternative. So, let's take a seminar. You're doing a seminar or workshop. You might get a response rate on...let's say, if you do old school mailers, you might get a response rate of a half percent. But if you're well branded, it could be over 1% because now you're a safe alternative. Right? Same reason that big pharma advertises all these prescription medications because now when the doctor actually prescribes that medication to you, oh, I've heard of that. Oh, yeah. Yeah. I know about that. That can help me. So, number one, branding helps your lead generation efforts become that much more effective.

But number two, it also helps your conversion ratios become more effective when people come to see you. Because, again, they're pre-educated, they're pre-tenderized to your message. So, now, when they come to see you, oftentimes they're that much closer to be ready to say, yes, I want to become a client, as long as you don't do anything to scare them off. So, you can't quantify it, but believe me when I tell you that branding works. And that's why companies all over the place spend so much money on it. That's why, out of our industry, you see all these Super Bowl commercials with these branding commercials. How can they justify that much money? Because it helps everything else down the path from there.

It's only in our industry that we don't seem to have enough patience to wait for branding to work. And my message here is to say that you should. You really should dedicate some of your marketing budget as a financial advisor to branding and being postured as that safe alternative.

Michael: So, when you say allocate some of your marketing budget, I mean, do you quantify that? I know you've got a numbers background. So, I don't know if you've got a "For every $1 we spend on branding, we spend $3 on marketing" or vice versa. Is there some split or allocation you think about or just I want to have a certain number of branding assets out there, like I need a book and something else, and then I've made my branding investment and now I can chug along with my lead gen? How do you think about the allocation resource?

David: Well, it depends on your stage in your career. At the very beginning, you're probably spending 80% on lead generation because you need to have more activity, and maybe only 20% on branding. But as you get bigger, there's people that go nearly 100% on branding because they've developed a bigger name. They have a bigger clientele. They're getting a lot of referrals. So, now, they truly want to attract, and they'll flip it to 80% on branding and only 20% on lead generation.

Michael: It's an interesting way to think about the evolution. So, is that how it's migrated for you as well? Would you characterize most of your marketing budget now as heavy on the branding and light on the lead gen because the branding is attracting the lead gen anyways?

David: It had for years, yes. Now, what's changed more recently is, because we have separate companies where we also coach and mentor other financial advisors and help them, it's taken a lot of my time. So, right now, to grow my business, the big metamorphosis is going into a multi-advisor practice, hiring advisors, bringing them on, and supplying them with scheduled appointments so that we can grow that way. So, in other words, instead of me being the lead advisor, I'm really the CEO running the company. And we brought other lead advisors in and helped them fill their schedule with quality appointments. So, in many ways, we've now gone back to doing more lead generation because of the commitment to these advisors.

David's Income-Focused Investment Strategy [30:40]

Michael: So, now, take me back to the investment strategy side of things. I'd love to really understand, I guess, get into the nuts and bolts a little bit more. You highlighted earlier just one of the distinguishing things for the investment strategy is we don't just have the income sleeve to pair with the gross sleeve. The whole portfolio is built around generating income. So, can you share with us more just how does that work? What is the portfolio construction process? What are the tools or the vehicles or however it is you bring this together to make the income-centric portfolio for retirees?

David: Well, first of all, I'm a big fan of individual securities much more than I am mutual funds or exchange traded funds. And I find there's a bunch of reasons why from a management perspective, but also because it helps differentiate you. I feel like a lot of advisors have gone to mutual funds and now ETFs because it's more scalable for them. And when you're still doing individual securities as an independent advisor, not one of the big wirehouses utilizing an SMA [Separately Managed Account], where there's extra layers of fees, but literally managing that, they look and say, wow, Dave's actually doing work. He's actually rolling up his sleeves and managing my money.

Moreover, what I find is that when you get into a bear market and those do...we haven't seen one really in a while, but they happen. You get into a bear market and all of a sudden, if you've got ABC Mutual Fund and XYZ ETF, they don't really know what those are. All they know is that, hey, Dave Scranton is losing the money, and I need to go to another advisor. But if they look in the portfolio and they see blue chip stocks that pay a nice dividend or bonds or preferreds from large U.S. companies, it gives me a little bit of a get out of jail free card during those time because they look at those and say, it's not really Dave's fault. He's got me in good blue chip companies. It's just the market. So, for example, it was one of the surprise findings for me was during the financial crisis in 2008. We had incredible retention. And remember, in the financial crisis, you weren't safe anywhere.

Michael: Everything was awful.

David: Preferred stocks were down 30%, 40%. Right? So, even the most secure stuff with a par value, it didn't matter.

Michael: I remember a prospect that came in in very early 2009 because they were loaded in Lehman preferred, and watched it be very stable until the day it got zeroed.

David: I know. I know. And it was...those are scary times. But I think the get out of jail free card that my clients granted me was they looked at the holdings and said, he's got us some secure stuff. It's not him. We're okay. And we had very little client turnover during that time. And that was wonderful.

So, we manage individual securities. On the equity side, the stock side, it's basically higher dividend value stocks. And as you're aware, you need to be careful when you're trying to analyze value stocks. In many ways, picking growth stocks is an easier ask because you're simply...with a growth stock, you're buying things that have upward momentum. Maybe you're trading stop losses and you're riding the momentum as long as it'll last. With value stocks, you're dealing with companies that are at the mature part of the corporate life cycle. So, that's why they pay higher dividends. So, now, the question becomes, okay, is it the beginning part of the mature part of the life cycle where there's still some opportunities for extra market share, or are they at the end where they might approach decline, where maybe the company cuts dividends and then the price goes down? And that's what we call a value trap.

So, with high dividend value strategies, you need to be very, very careful. So, we have two. We have one that pays a dividend yield of, I think, 4.7% today and another one that's down in the lower threes. That's a little growth here. But again, you've got to be really careful when doing that because it's not as easy as just riding momentum.

On the bond side, I have a strategy which our CIO can't stand, but I call it bonds and bond-like instruments. And he cringes every time I say that.

Michael: He doesn't like bond-like instruments?

David: Yeah. He doesn't like it. There's more technical terms and that's great. But it's something I stumbled on really back in 1999 when I first did this. I had a theory. And if you follow me on this, I took Modern Portfolio Theory, the efficient frontier. And the whole point of the efficient frontier is I can add something that has more volatility risk to a conservative portfolio. And as I add that thing with more volatility risk, over time, I'm always going to get more return. My return goes up. Right? So, when you graph the efficient frontier on...it's the Y axis. Right? It goes up. But the risk, at first, when you add a little bit of that riskier thing to the more conservative thing, the volatility risk actually goes down because of the benefits of diversification. Only when you add too much of the riskier thing does it go back out again.

So, usually, they talk about stocks versus bonds when they're talking about the efficient frontier. So, I said, well, what if we talked about bond-like equities? What if we talked about things...put in some preferreds. What if we talked about things like real estate investment trusts, which in many cases are a bond-like equity? Because they're backed oftentimes by long-term leases from tenants, and in more recent days, even BDCs, business development companies. REITs and BDCs are the stock essentially that...a bond-like stock is what I like to call them.

And by adding a little bit of those to an income portfolio with mostly bonds and some preferreds, what I found was I was able to increase the yield, increase the return, and over time, minimize the volatility risk. Over time. And what that did was, gosh, a few years ago in the bowels of the interest rate environment, when the ten-year treasury was at 1.5%, we were able to consistently get 5% yield in our portfolios of bonds and bond-like instruments. So, that means if you charge a 1% fee, your clients were getting 4%. So, instead of using the 4% withdrawal method, withdrawing principal and hoping it grows back, we literally were generating 4% for clients after fees even then. And of course, now, it's 6% or higher in many cases because interest rates are much, much higher.

So, that's the theory on this, what we do with the bonds and bond-like instruments side. Again, 26 years ago, it was just a theory. But since then, we've proven it out to increase yield, increase return, and decrease volatility over time.

Michael: There's something to me that's very amusing about how our industry plays out in cycles that...I mean, I guess probably to your timeline, having started in the late '80s, it was the heyday of selling stocks. And the novel differentiator was selling professionally managed mutual funds. And then we had a good ten or 15 years of that, and then "everyone owned mutual funds" and the differentiator was using this new-fangled ETF thing. It was more liquid, it was lower cost, it had cool tax efficiencies. And we did that for ten or 15 years. And now, the cycle seems to go fascinatingly full cycle. And now, the differentiator to all the advisors who own some funds and lots of ETFs is back to owning individual stocks.

David: Right. So, Michael, what does that tell you? That means those bell bottoms that are in the back of your closet, keep them because they will be back in style.

Michael: They're going to come back.

David: That's the point.

Michael: I'm just looking forward to the big hair coming back. It's fantastic.

David: Yeah. Things do go full circle like that. But one cycle that's happened...and I want to say this in the nicest way because I want to help your listeners, your followers. And I don't want to insult anyone. And I know that a majority of advisors today generate income through something that's directly or indirectly tied to Monte Carlo analysis, most of the software that's out there. We'll talk about how much money can you safely withdraw from a portfolio without...with a minimal chance of running out of money.

There's several problems I have with that. I mean, first of all, I think about what's an acceptable tolerance? Well, if you say, well, 90% is an acceptable tolerance. I've got a 90% chance of certainty that I won't run out of money. I said, well, is that really acceptable? Because if you've got 100 clients and you have a client appreciation party that you throw, ten of those people are likely to run out of money, mathematically speaking. And as a pilot, it's the same thing as if I said, Michael, hey, come on, get my airplane. I'm going to fly you back to DC. Don't worry, though. There's a 90% chance we have enough fuel to get there. You're going to run for the exit door as fast as you possibly can.

Michael: Baltimore is lovely at this time of season as well. We can leave a little early.

David: Yeah. I believe what happened, and I have an illustration that I can't really do any justice to over a podcast without the visual. But when you start to build a plan... Think about how we're all taught to build plans. We're taught that if I came to you and said, look, I have a million dollars. I just want to grow it for ten years. And Michael, I'd like you to tell me how much income I can generate from this money starting ten years from now. So, I'm going to grow it for ten years and then start taking income.

Michael: Okay.

David: We're taught to do a two-step calculation. Right? The first step is, okay, what's that going to be worth in ten years?

Michael: Yup. Future value from here to there. And then I've got some future value in ten years. And then I can calculate some kind of withdrawal or yield thing off my future value at ten-year future.

David: That's right. So, let's say, if it's 7% assumed rate of return for ten years net of fees, it doubles. So, now, a million becomes two million. And if you're using the 4% withdrawal rule from the old Trinity Study, well, now, you're getting $80,000 a year. So, most advisors would say, well, it looks like you're going to get about $80,000 a year. And I say, well, that's...okay, that's great. But what happened if you put this plan together for me in January of 2000? You put this plan together in January of 2000, and I show up your doorstep ten years later. January of 2010, I go, okay, I'm excited. I'm ready to retire. Give me my $80,000 a year.

Well, all of a sudden, you're not going to get that. You're going to get a lot less. Ten years later, if you're in the S&P 500, for example, you're probably still down 20% to 30%. You don't have a million. You have 700,000 or 800,000. Right?

Michael: Right.

David: And am I going to want to sell those investments ten years later at a loss and retire? Probably not. And let's face it. Prospective clients don't want to build a plan on hope. They want to build a plan on what we know is likely to be true. So, what do we know? We know what dividends are getting paid. Right? So, if you said, over that time, the S&P 500 had an average dividend of 15%...or sorry, of 1.5%. That means what I know is my million dollars would generate $15,000 a year. And I know that if I reinvested that $15,000 for ten years, I wouldn't have a clue what the lump sum is going to be worth. But what I would know is that the income would have grown from $15,000 to $18,000 a year through the reinvestment.

So, if I were being brutally honest with that client, and in the spirit of full disclosure, I would say, you know what, the income...the answer to your question, David, the income that you're going to get starting ten years from now will be anywhere between $18,000 and $80,000 a year. Okay? Now, here you go. I've prepared all the paperwork for you to transfer your million dollars over to me. Go ahead and sign right here. Press hard. There's three copies. Right? Well, you have to ask yourself, what are the chances that I'm going to get that person as a client that day if I told them it's going to be between $18,000 and $80,000 a year ten years from now? Obviously, not very good.

So, the industry had a dilemma. The industry had a dilemma years ago because they said, look, we want to keep people in the stock market. We want to keep people in growth because over time it helps the industry. Financial advisors can charge higher fees. Firms can make more money off fees and commissions. So, we want to keep people in more aggressive stuff. But if we do that and we fully disclose what could happen, that disparity is going to be so big, such as the difference in $18,000 and $80,000 a year of future income, we're not going to get any business. So, how do we fix this?

That's when the spirit of, full disclosure, the industry realized, well, wait a minute, there's this off the shelf mathematics that's used in other contexts where we can use this Monte Carlo analysis, and we can fully disclose. And if we change the rule and say, well, the rule isn't living off the residual, the income, the interest and dividends, the rule is spending down principle. And if you die with a dollar left, that's called success.

Now, what that does is that changes the rules a lot. You're taking two different probability curves, one of life expectancy and one of distribution of market returns throughout retirement. And you're overlapping them. So, now, it allows you to turn the knobs, fine tune it, and get the chance of failure down to 10% or less. So, in the spirit of full disclosure, Monte Carlo allows advisors to have full disclosure, and still be able to sell goods, products and services and everything else.

The problem, though, especially if you're a younger advisor, if you're sixty years old like me, well, okay, by the time my client runs out of money, well, I'll probably be dead. So, it's not a big deal. But for those of you listening that are in their 30s or 40s or early 50s, that may not be true. They may have to be the ones delivering the message that 10% of their clients, hey, you are going to run out of money. This is a problem. And that's not fun. And let's face it, the only real way to know that you're never going to run out of money is by never taking a dime of principal. If you don't take principal, you can't run out of money. It's that simple. And that's the message, and that's the structure through which all of our assets are managed.

Michael: It's fascinating to me that there is this striking concreteness that shows up for clients when we move away from pooled vehicles and into individual holdings. For me, it first hit home in the early 2010s in conversations with clients who were anxious about their bond funds when rates were so low after initial Fed quantitative easing. And back then, we weren't even just talking about fear of rising rates. We were talking about fear of inflation spikes and the risk that inflation would rise rapidly.

And just I remember these conversations with clients that they were just terrified of bond funds and what happens with duration and rising rates. And somehow it was completely okay if they held individual bonds because it always came back to, well, I can just always hold the bond in maturity and ensure I get my money back. And it was like, well, the fund can do that, too. It's just an aggregation of your individual bonds, but it showed up so differently in how clients thought about holdings. When I can see the thing and see it mature to par or when I can see the name...as you highlighted earlier, when I can see the names of the stocks. Oh, yeah. Dave didn't put me in a bunch of losing investments. I can see the companies. These are good companies. It must just be the markets. It might be the same companies, like the big funds kind of hold similar stocks, too. There's only so many of them, but the client psychology is just so different to me in fascinating ways of client psychology that they really do seem to show up differently in ways that on the whole are usually constructive.

David: Well, there is some materiality to that, to being able to hold to maturity. And I'll give you two examples. An old friend of mine, and I know the name is very similar to yours, but Michael Tripses, who is an actuary, one of the early actuaries that actually invented indexed annuities, for example. And he said to me at one point, he says, you know, bond funds are stocks. And I thought, okay, he's an actuary. This is either going to be really profound or probably really stupid. Nothing in between. Right? But what he said was really profound. He said, because, look, whenever the value of my holding gets permanently affected by what other investors do, that I consider it a stock.

And of course, what he was saying was that individual bond, he holds it to maturity. He knows what he's going to get, but in a bond fund, if interest rates are coming up or spreads are widening and causing the prices to drop, and people panic and sell, that fund manager has to sell at a loss. Even if he's the most disciplined investor and doesn't want to sell, he's losing money, and it's not just on paper. So, that was the first thing that I heard when Michael said that to me and I said, okay, that's profound. I love it. I agree. Because that was my philosophy.

But the second time was 2016. In 2016, I was studying for the Series 65 because I never had to take it. I was grandfathered because of my designations. In 2016, a lot of people were failing the tests, and I got frustrated. And I said, I'm going to study, and I'm going to take the test. I'm going to see why this thing is so hard. Maybe I can help talk other people through how to pass this. And when I was studying it, I remember reading the definition of a bond mutual fund. And my memories of that conversation with Mike Tripses came back when they said the definition of a bond fund in the study guide is the stock of a company that owns bonds. And I thought, wow, wow, that even sounds riskier. So, yes, you're right. It...

Michael: It really does when you say it that way.

David: Yeah. And so, in the court of public opinion, you're right. There's a truth, a feeling, but it's not just opinion. There is some truth to back that up. So, we go with that direction. We paddle with the current. Why paddle against the current when you could paddle with the current and give people that sense of comfort?

So, in fact, I'm less anti-fund on the equity side than I am on the fixed income side, because, yeah, there might be some disadvantages with equity mutual funds. A recent Barron's study said 92% of them underperformed the S&P 500. And a lot of it is because a lot of them are closet indexers. So, they're worried about underperformance. And then when you throw in the fees and the fact that sometimes they get so big that they can't get most efficient fills on their execution, whether they're selling or buying, they sell, they drive the price down, they're buying, they drive the price up because they're so big that it's no secret they actually underperform. But even then, I'm less opposed to mutual funds and ETFs on the equity side than I am on the fixed income side.

How David Constructs Income-Generating Portfolios For Clients [50:22]

Michael: So, now, paint the picture for us of how this comes together as a portfolio. I guess I'm just trying to visualize. How do you allocate across these different...the holding level, the category level, the asset class level, the grouping level. How do you build the allocations? How many holdings do you end out with? Help me visualize what a client's portfolio statement's going to look like when they're invested this way by your approach.

David: So, first of all, one point of differentiation that's different for us than many...and frankly, I figured out how to do this because when I looked at all of the most successful financial advisors in our industry, they would all...they wouldn't do proposals for free. They would get people to commit to ACAT transferring the assets to them before they did all the allocation work. And if we have time, we can talk about why that's a more successful way to convert a prospect to a client. But the point is that when people buy us and they transfer assets, all they know is they need to start transitioning to an income-first capital-appreciation-second approach. They don't know anything about how they're going to get there.

So, then once the money is here, we actually sit down and educate them about, as I like to call it, the universe of income-generating options. So, first of all, we talk about insured options. So, we talk about things like bank CDs, government bonds backed by the government, and we even talk about fixed indexed annuities. Then we get into what I call non-insured contractual things, which are bonds, various bonds, preferreds. They have a par value that have a stated coupon rate. Then we get into things that are more equity-oriented that have more income, but the income can fluctuate. And this is where BDCs, real estate investment trusts, and high dividend stocks. You have essentially three classes. You have insured, you have assured that are where the income is assured by the issuer, but they can still default. And then you have the non-assured, but still things that generally pay more income.

And by educating people and talking to, number one, their income goals, as well as their risk tolerance, we start to put something together there. And where annuities come in, for example, is because when you compare all the insured instruments and you look at bank CDs, which you can't lock in a good rate for more than 12 or 18 months, and even those rates are going down now with the Fed's most recent moves. A ten-year treasury at roughly 4%, well, that doesn't quite cut it. So, all of a sudden the annuities are the best of all the insured items. So, it's clear that whenever somebody wants something that's insured, that's principal-protected, the annuity is the winner.

Then when they go down to the contractual compartment, there's a couple of different iterations of what percentage in bonds versus preferreds. And then they can...we determine that. And then when they go to the non-contractual, the riskiest, this is where people's risk tolerance comes in. And Michael, to me, it's really simple. It's, okay, you invest because you want upside potential, but that means there's more...there's also downside risk. So, you start with a million dollars. Right? Are you okay if in order to attempt to get growth, it drops to 900? Are you okay? Are you okay if in an attempt to get growth, it drops to 800? Where's your pain point? And I ask the question, imagining that they were retired, and some are and some aren't.

And that's where I figure out their pain point. I figure out, okay, they can only take a 20% drawdown and that's it. And then having previously stress-tested our portfolios, I know that, okay, this is the most they can put in the non-contractual territory to keep them within that desired drawdown. And that's it. And for some people, who were willing to take some risk. It's I need goals versus I want goals. Well, I need to make $100,000 in retirement, but I'd like to make $150,000. Okay. So, we'll invest enough in the contractual things to get them $100,000 a year. And then we'll use the non-contractual things that have more upside potential to get an extra 50, so that even if those things don't do so well, they can still...if companies cut dividends like happened in the financial crisis on common stocks, then at least they've got all their needs met.

So, just educating the client once they ACAT transfer the money over, once they hire us, and then building the portfolio with them. From a conversion, from a sales standpoint, Michael, it works great also because the most analytical engineer wants to be part of the process, but they're not going to hyper analyze all the stocks you're going to put them in, all the preferreds you're going to put them in, all the bonds or the annuities. They're just not. So, they have a hand in the macro picture, but they're leaving it up to you to take care of the micro. And it works great for analyticals. It really does. Early on in my career, when I switched to this process, I actually got into a network. I worked with a ton of engineers. And in fact, I became known in my office back then as you have an engineer, you can't convert, bring them to me.

Michael: Bring them to David.

David: Yeah. And it works because they get to be part of this process, and they want to be, but to a certain level.

Michael: So, how many holdings do you end out with if you're doing a lot of this with individual securities as well?

David: So, for whatever portion is in common equities, we'll typically have 30 to 40 holdings. Whatever portion is in what I call bonds and bond-like instruments, we'll have between 50 and 80. A combination of...

Michael: And that's often just a slew of individual bonds, individual preferred stocks and the like, like I'm still getting line-item securities with standalone CUSIPs?

David: That's right. That is correct. And again, it's a great uniqueness.

Michael: How do you scale and execute the trading management of this? Because I'm struck. I mean, you've got individual securities, where you can potentially start getting into liquidity challenges for individual holdings that you're trying to sell. You've got different clients that want different splits across the three classes. So, I don't know how finely graded that can be if every client can be different or if there's still a series of models of varying risk levels so you can have clients a little bit more standardized. But how do you scale the trading and management of this?

David: Yeah. It's clearly not as scalable as a portfolio of ETFs or mutual funds. It's really not. But I've always said, I want to do things the way that I think is right, not necessarily the easiest way. So, even if it hurts my margins, I'm okay with that because I'll make up for it because I'll be so passionate and excited about what I do that we'll end up with way more assets under management. So, to answer your question, what we've done to make it a little simpler is to say, let's have a limited amount of combinations and permutations of how we put these assets together. And of course, you have...the two biggest platforms in the world for money managers that I'm aware of is Black Diamond and Orion. And we actually use both of those, but for different functions. And therefore, you program all of these in as sleeves based upon these different combinations and permutations. And frankly, we have over a hundred different ones. And that helps, but that's not even the toughest part.

The toughest part is trying to get a good fill. Any of your followers know that, if they've worked on the Series 7 side, that you go buy a bond through your trading desk, and you're probably not going to get the best fill. There's a lot of stuff padded onto the price in both directions. So, what I had to do is really invest in the right people. First of all, I mean, we probably have, gosh, eight or ten Bloomberg terminals rolling around the office here. And those aren't inexpensive.

Michael: Oh, no, they're not.

David: But people who know how to do trade-aways, how to go negotiate with bigger firms and say, hey, I know you're looking to get rid of this. We want to buy it and negotiate one on one and take out the middleman. So, for example, when we do individual bonds, 90% of those are trade-aways. They're not done through a clearing house. Now, we need to pay a fee ultimately when we buy a block of those, and we insert them in people's portfolios, but it's still a better fulfillment for the client. And when I can look a client in the face and say, these are our points of differentiation. We're going to do the work. We're going to buy individual bonds and preferreds. We're going to do the research. We're not going to put you in a pool. Because every pool has some good holdings and has some nonsense in it that you...I'm sure you can look at any fund, Michael, and find some holding that you would say, gosh, I wouldn't invest my worst enemy's money in this whole thing. Right?

So, now, you don't have to deal with that. You do the actual work, do the research, you pick the things that you like. And you go out and negotiate a good price. Your clients get a better price. And when you can tell that whole story, that's a sticky relationship. It's a much stickier relationship because financial advisors have allowed themselves to get commoditized by prospects. That's what's happened recently. We've gotten commoditized. And the thing that differentiates is service or maybe some independent people being able to do some tax planning and some other things. But the actual investment process is more commoditized. And I'm too stubborn to let the prospect commoditize us. And that's the big part of what this strategy does, is allow us to not be commoditized.

Michael: I mean, to me, there's an interesting balance to this. On the one end, I'm sure there are some folks listening that are just saying that this just sounds too hard. It's too much work to do the trading execution end of it. And then on the other hand, there's a part of me that just reflects, I'm going to bastardize the quote, but a version of what someone had said to me when I was early in my career is, part of differentiation success is doing the hard things that other people don't want to do, that part of what makes it work. At the time, I think that was used as a justification for why I should keep cold-calling when no one else wanted to cold-call, selling variable universal life to strangers. But the principle remains sound.

As you've highlighted, when scaling this kind of training, it's hard. A lot of us have converged into much more readily tradable funds and especially ETFs these days. But when we all converge there, because that's the easily tradable thing to scale with clients, we can unwittingly start to commoditize our investment process, which I'm not sure any of us entirely fully realize or think of our investment process being commoditized until you start talking about, yeah, we've got Bloomberg terminals and people who know how to negotiate individual trades for bonds and preferreds. And a whole bunch of us are probably going, yeah, I don't do that.

David: Right.

Michael: Nope. I don't do that. Right? That sounds really hard.

David: It can be, Michael. But I would tell you, I've taught lots of independent financial advisors how to do this. The bonds and bond-like instruments from an analytical standpoint is much like credit analysis, as you're aware. It's not that hard. Value stocks is much more difficult, but what a lot of advisors will do is use an ETF for more of a value stock strategy or something else that they don't have to do that part of the work. But they get 80%, 90% of the credit that I get from clients by doing the bonds and preferreds and things like that with individual issues. They really do.

So, it's not as hard as you think. You have to start somewhere. And again, I've taught a ton of people how to do this. A good friend of mine who's an advisor out of Tulsa says when he's talking to prospects, he calls it the disease of ease. He says, advisors have fallen into the trap today that they figure they don't have to do much work. They can outsource a lot of it to other people, and sit back and just collect the fee. And then you're paying a second embedded fee somewhere for some outside firm or some outside fund to do the management. He calls it the disease of ease. And he says, I'm not going to do that. I'm going to do the work for you, do the research. And that's attractive to people.

So, ultimately, you've got to say, okay, what's scalable is fine. But am I just in the business to make it scalable, to make a good living, or do I want to put my stamp on a legacy and build something that I'm really, really proud of? And my stage in the career at age 60 and with the success we've had over the years, it's more about building something I'm proud of. It's not about money any longer. And that's what drives me. Even if it complicates our life, if I feel like it's the right thing, well, gosh, darn it, I'm going to do the right thing, even if it's more complex.

Michael: So, in a moment, I'm going to ask about what all this adds up to, as it were, the state of the firm. But first, you piqued my curiosity once more. So, I've got to ask. Why Black Diamond and Orion?

David: Well, those are generally considered the cream of the crop when it comes to reporting.

Michael: Yeah. But most of us buy one of them.

David: Yeah. So, we actually use one for reporting and one for trading because we want to get the best of the best. And Orion's trading is hands down better. Black Diamond is working on it, and they're trying. They're probably close to a year away from really upgrading that system.

Michael: So, Orion for your trading platform, but Black Diamond, you like the reporting side more.

David: Yes. And Black Diamond is way more cost effective than Orion. And on reporting, I feel like they're neck and neck. But trading is where Orion really shines, especially when you're complicating your life, like I like to do with all the different sleeves and combinations, permutations. Well, then you need state of the art trading software, for sure.

What Sound Income Group Looks Like Today [1:04:55]

Michael: Okay. So, now, just tell us about the advisory firm as it exists today. What is the state of the business of having now been executing on this income-driven strategy since 1999?

David: Sure. Well, we have firm-wide...and we have other advisors that I've taught this to that ask us to manage the money for them. And we add all that together. We have over four billion of AUM right now, and growing from there. And because a lot of it is income, it's not so much organic growth, it's not growth because the markets have gone up. It's growth because the branding and the lead generation strategies bring more people in, and they transfer more assets. So, the strategy has worked phenomenally well.

And frankly, I will say that when we started the RIA just a little more than ten years ago, we started with $50 million. That was it. That was really it. And then we had to grow it over time. But again, that's the benefit of having a uniqueness. That's the benefit of having something where maybe everybody doesn't want your message, but if you're the only one who's really doing it in a unique way, well, then you're going to own that market. All they have to do is buy your message, and they're going to be with you because there's no place else for them to go.

Michael: So, how does four billion breakdown just in terms of number of clients, number of advisors, total size of the team? How many people are on both sides of this, clients and team?

David: Well, in terms of number of offices, there are about...and I'm going to guesstimate here a little bit because I don't have the exact...the exact number changes. But there are about 40 offices that are involved. And a lot of them have multiple advisors because I might have a licensed service advisor who's doing the reviews, the client reviews, or they may have what we call an acquisition advisor who's out there bringing new assets in, doing that kind of thing. But there are about 40 firms that are part of this. And households, we have over 10,000 households.

So, you do the math real quick. We're working with Ma and Pop. We're not working with affluent individuals. We're working with average folks, and you could be very successful doing that. Everybody's chasing after the really affluent individuals. And I grew up in a blue-collar town, Bristol, Connecticut, of ESPN fame. I was there before ESPN. My mother worked in a factory. My father worked construction. And to me, I need to help average folks. And today, even if you have a million or two, you can't be careless. You can't make any mistakes because that's not a ton of money to live on.

So, yeah, we've morphed to what you call mass affluent. But why aren't I chasing after the biggest accounts? Well, it's not my passion. It's not what I want to do. With my credentials, could I get them? Sure. But let's face it. If you've got 10 or 20 million, you're probably going to be okay no matter what you do. But if you've got 500,000 or a million, you've got to be careful.

Michael: And so, in this four-billion environment, because it sounds like you've got clients you work with...are you also doing this on a outsourced back office environment for folks that you could access through a TAMP or an SMA path? Is it some of each? How does the advisory support breakdown of who's part of your firm and who are you a service provider for?

David: My practice in New England really consists of right now about 12 advisors. There are eight people that are bringing in new clients that we're marketing for, we're generating leads for. We're getting their calendar filled with qualified prospects, and their job is to kind of pull them over the line. And then we have four service advisors that are doing all the client reviews. And while they're doing client reviews, they're oftentimes getting referrals and getting additional assets. That's 12 advisors there.

But the rest is through the rest of the firms, these other firms that I've just worked with over time and helped coach and mentor them. And some of those are investment advisor reps through us. And some of those are their own RIAs. They're just using us as a sub-manager because they looked at this and said, hey, we don't want to do all this work. We like the message. So, here, can we just let you manage it? It'll make our lives easy. So, we do that, too.

Michael: Okay. And so, you end up with just different pricing options for each, depending on how advisors want to affiliate in or be involved?

David: That's correct. That's correct. It didn't start that way. Again, it started...I started as a Series 7 broker, doing these things on a brokerage platform, and went the investment advisory route, quite frankly, because a lot of advisors that I'd known and I taught how to manage money, said, we appreciate this. We appreciate that you taught us how to do this. But the reality is it does eat up some time when we get a bond called or a preferred called and we need to find a replacement. And they said, Dave, you've always taught us that our time is worth a thousand dollars an hour when we're face to face, knee to knee, elbow to elbow with a qualified prospect. So, the highest and best use of our time isn't finding a replacement for the security that just got called. Can you manage it?

So, that's when we started the investment advisory firm, and really haven't marketed, haven't actively tried to recruit people to it. But again, because we're really one of the very few that are in that space, you just start to attract people without even trying. And again, that's the benefit of differentiation. This happens to be an example where as more...in a wholesaling entity, I'm differentiated, but that's also the benefit of differentiation when you're dealing with clients. Whether you have a follower, Michael, that has a practice and has one part-time assistant or you have a follower that has a couple other advisors in his or her office and has several staff members. That first step to attracting, not chasing, is that differentiation.

When I was young, I think my testosterone levels were higher, and I loved cold canvassing. I literally would go in industrial parks. I'd knock on doors. I'd ignore the no soliciting signs. And I try to get through the presidents and CEOs to get people. And I thought it was fun. I thought it was a hoop. But as we get a little older and we do have an aging population in our industry, maybe if you're a guy, maybe your testosterone levels drop a little bit, and maybe you want to class your way to get prospects. And that's when I suddenly became a student of this attract instead of chasing methodology.

Michael: Well, it's just striking to me at the end of the day for all the discussion that you "have to" go upmarket, there are some economic benefits to doing so. You can scale with Ma and Pa. Right? I mean, just we can do the math. Average household is $400,000, and you've got 10,000-plus of them and many billions of dollars under management. And you're doing it with "harder to implement" investment strategies. We're not even in the...it's highly scaled because there's four ETF models and we hit the button. Like you have real trading work to do to get good order fills. And it seems to have grown okay.

David: Yeah. Twenty years ago, before I really started mentoring advisors at any large scale and growing the practice beyond me, when I was the advisor, the producer bringing in business 20 years ago, I was bringing in $60 million to $80 million a year of new business. And of course, the accounts were a lot smaller then. The S&P was a fifth of what it is today. And how I did it with Ma and Pop was, again, I knew that my time was worth a thousand dollars an hour when I was face to face, knee to knee, elbow to elbow with prospective clients. So, what I would do is I did enough lead generation. So, I'd have a meeting pretty much every hour on the hour with a prospect. And I learned to delegate everything else in my office. I had people doing paperwork, people making up on phone calls to keep my calendar filled, an advisor who would service and do reviews. And I literally did all that. And I was able to bring in that $60 million to $80 million with Ma and Pop just from keeping the schedule filled.

And so, there's another change that people need to make. First is to realize that, okay, my time is worth a thousand dollars an hour. I've got to step on the gas. I have to do more marketing. I need to get in front of people, and fill my calendar with qualified prospects. But you also know that if you drive your car with the pedal to the metal, you're going to burn out your engine. It's not going to last forever. And so, eventually, then you have to go into...go down the...set a maximum speed, go down to cruise speed, pull your foot off the gas. And now, you have to teach yourself another skill set, which is learning how to work on your business, not just in your business. Because you can only run on that treadmill so fast.

So, I find a lot of times with advisors that that's a...first, they need to figure out what max capacity is and how fast they can run. But then they need to pull back and develop that management skill, that leadership skill to truly build an organization, because otherwise you burn out. And if you're going to be burnt out and hating your life and your career, that doesn't do anyone any good. Not your clients, not your employees, not your spouse or children. So, those are some of the iterations that I had to go through throughout my career. And I find that other advisors get there, too, in time.

What Surprised David The Most Building His Advisory Business [1:14:55]

Michael: So, as you reflect then on this journey overall, what surprised you the most about just building this multibillion dollar advisory business?

David: Well, first, I think one thing that surprised me was stumbling on to this income model as a great attraction opportunity, also that people say you are who you are, you can't change. Well, I disagree. Part of the reason the first eight years in the business I literally was failing was because I couldn't sell. I was the most analytical guy out there. And I read books about successful people and realized that most successful people aren't that analytical. And I set out with resolve to beat the analytical out of me, which I've subsequently done. And ironically, Michael, today, if you give me an analytical project in front of a computer, I get chest palpitations. So, I've literally rewired how my brain works in order to be successful. And that was a big learning, too. So, anybody listening who says, well, I am who I am and I can't do what Dave does or what Michael does, well, that's not true. If you want it badly enough, you know what? You can change who you are if it's for the greater good.

Michael: So, how did you retrain yourself into this more sales oriented, sales capable capacity? What were you doing to make it happen?

David: Well, there's the fuel and then there's the technique. So, the technique was realizing that no matter how smart I might be, that I don't have all the answers. I need to put my ego in my back pocket, and I need to get mentors who can teach me. And then I have to copy precisely what those mentors do. In other words, not just...like a lot of sales guys, just get the gist of what they're doing and kind of sort of do it. I said, I'm going to copy exactly what this mentor tells me to do, and I'm going to do it in exactly the same way. So, that was a big part of the technique.

The fuel was just being goal oriented enough, wanting it badly enough. And part of it is you have to have people who have a little bit of a chip on their shoulder, a little something to prove, often do really well because they've got that fuel that drives them. And I had that. I grew up as an only child. I lost my dad when I was three in an occupational accident. So, when your husband comes home to my mom, he leaves in the morning and says, honey, I'll be home that night and says...he never shows up because this occupational accident, which he was killed, mom becomes a little bit overprotective. So, I never got to do all the things the kids do. And I was a little sheltered. And that leaves a little chip on your shoulder. I've got something to prove. To whom? I don't know. But that's the fuel, that goal orientation that with the right technique and the right mentor got me for...got me to make that paradigm shift and, as I say, beat the analytical out of myself.

The Low Point On David's Journey [1:17:55]

Michael: What was the low point on this journey for you?