Executive Summary

While most income tax planning is focused on minimizing Federal tax liabilities, the reality is that with state income tax rates as high as 13.3%, strategies that reduce state income tax liabilities are increasingly popular as well.

A recently popular strategy is the so-called “NING” trust, an extension of the DING trust where portfolio assets that may generate significant income are contributed into a Nevada trust to shift the tax exposure to Nevada’s 0% state tax rates, rather than the settlor’s high-tax-rate home state. The end result can be a significant state income tax savings, while avoiding any unfavorable gift tax ramifications (and for higher income individuals already pegged to top Federal tax brackets, no adverse Federal tax consequences). And as an added benefit, the trust itself qualifies as a Nevada asset protection trust (indirectly necessary for the favorable tax treatment!).

Unfortunately, the non-trivial costs to create and manage a NING trust, along with the potentially unfavorable Federal income tax treatment (for those not already at top tax rates) limit the appeal of the strategy for most. Nonetheless, for those who do have significant assets and income, and investments with significant tax exposure, a Nevada trust structured as a NING can generate substantial state income tax savings… at least, until the remaining high-tax-rate states follow the recent actions of New York and crack down on the strategy altogether!

What Is A NING Asset Protection Trust?

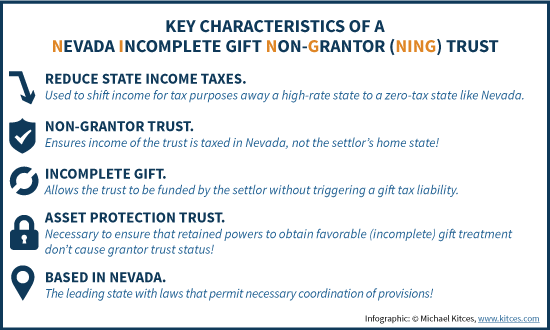

A “NING" trust is a “Nevada Incomplete-gift Non Grantor” trust, and is used primarily to reduce state income tax liabilities (while also obtaining asset protection benefits).

The idea of the strategy is that someone who has significant potential income or capital gains – for instance, a multi-million-dollar portfolio – which in turn may be generating both significant Federal and state income tax liabilities, can try to shift the income from their current state (where the individual lives), to another state that has more favorable tax treatment. Notably, the goal is only to generate state income tax savings, as Federal taxes will be due no matter what.

For instance, imagine an investor who has a $10,000,000 portfolio, comprised heavily of low-basis stock (a cost basis of only $1,000,000). In a state like California, the annual dividends from the trust, along with the capital gains when the stock is sold, will be subject to a California tax rate as high as 13.3% (in addition to Federal capital gains tax rates as high as 23.8% including the 3.8% Medicare surtax on investment income). For a looming $9,000,000 capital gain, the tax liability for California alone is almost $1.2 million, in addition to almost $2.2 million of Federal taxes! However, if the individual lived in a zero-tax-rate state like Texas or Nevada, the stock sale would still trigger $2.2M of Federal taxes, but would entail zero capital gains taxes at the state level, for an outright tax savings of $1.2M!

Of course, the investor could potentially obtain this treatment by simply moving to the state with the more favorable tax treatment. Yet the reality is that, even for such a significant tax savings, not everyone wants to relocate themselves and family, and go through the process to change their state of residence!

The solution, then, is to transfer the stock to a NING trust, which is based in (and subject to) the tax laws of Nevada, not California. Accordingly, once the stock is inside the NING trust, when it is sold and the trust reports the gain on its tax return and pays its bills, the trust will face only Federal capital gains taxes, as the Nevada-based trust is eligible for the Nevada-based state income tax rate of 0%!

In the meantime, the assets in the NING trust may still ultimately be distributed back to the original settlor (subject to some constraints as discussed below), and/or to other family members. The end result – the money stays in the family, but enjoys a whopping $1.2M of state income tax savings by avoiding California income tax rates on the gain!

Proper Structuring Of A Nevada Trust As A NING – Non-Grantor Trust Status And An Incomplete Gift

The caveat to the NING trust is that in order to receive the favorable treatment, the trust must be drafted to carefully navigate through a series of tax laws to ensure that it is taxed in Nevada (and not the higher-tax-rate home state of the settlor), but that funding money into the NING trust doesn’t generate a big gift tax liability at the time.

NING As A Non-Grantor Trust

The first key characteristic of a NING trust that allows it to receive its favorable state-income-tax-shifting treatment is that it is taxed as a non-grantor trust. By operating as such, the NING trust is treated as a separate and distinct entity for income tax purposes, such that even if the person who funded the trust (the settlor/grantor) lives in a high-income-tax-rate state (e.g., California), the assets held inside the trust are taxed separately based solely on whatever state the trust is based (e.g., Nevada).

This allows the settlor of the trust to contribute assets into the trust, and shift the income tax consequences of those assets from the settlor (and his/her home state tax rules) to the trust’s (deliberately-chosen-to-be-more-favorable) state instead. Because real estate and physical tangible property is always taxed based where the property is physically located, this state-tax-shifting opportunity for NING trust assets is generally for intangible property (e.g., portfolio assets, and the interest/dividends/capital gains generated by those investments).

Funding A NING With An Incomplete Gift

The second key characteristic of a NING trust is that the transfer to the trust is treated as an “incomplete” gift.

In the context of a NING trust, this is actually a benefit – the fact that the gift is not completed means transferring property into the NING does not trigger the filing of a Form 709 gift tax return and require the settlor to use a portion of his/her lifetime unified credit amount for gift and estate taxes. So the settlor of a NING trust can obtain the income tax benefits, without triggering unfavorable gift/estate tax treatment.

Notably, the fact that the transfer of assets to a NING is an incomplete gift also always means the investments inside the NING trust will be included in the settlor’s estate, providing for a step-up in basis on those investments at death!

The Delaware DING Trust – Progenitor Of The NING Trust

Notably, the first type of income-shifting non-grantor incomplete-gift trust was not based in Nevada, but in Delaware – and thus went by the acronym of a “DING” trust. A DING trust was, similar to the NING trust that came later, designed to facilitate a shifting of state income taxes from the settlor/grantor’s high tax rate state, to more favorable Delaware trust tax rates.

The DING trust was sanctioned by a series of early private letter rulings affirming that the ‘strategy’ would work (e.g., PLRs 200148028, 200247013, 200612002, etc.), where the trust would be treated as non-grantor for income tax purposes, but still be an incomplete gift for estate tax purposes. The key provisions of the early DING trusts that allowed this to happen were:

1) DING Distribution Committee. The DING would have a “Distribution Committee” responsible for determining how much was sent out of the trust. The DING Distribution Committee would be comprised of the settlor and at least one other (adult) beneficiary of the trust, and together they would determine when distributions would be made out of the trust and to which beneficiary(ies). Of course, if any one person on the Distribution Committee had too much power, it could cause the assets of the trust to be in that person’s estate instead. Thus, a balance of powers was necessary.

For instance, the DING trust might stipulate that the distribution committee can only make distributions to the various beneficiaries based on the unanimous consent of the committee (which includes both the settlor and other beneficiaries who have an “adverse interest” to each other because distributions to one reduces distributions to the others). The fact that members of the Distribution Committee wouldn’t act alone ensured the trust assets would be in their estates. And because the trust could only make distributions back to the settlor by acquiescence of an adverse party, it would not be treated as a grantor trust (as desired) under IRC Section 672(a) either.

2) Testamentary Non-General Power Of Appointment. The DING trust would permit the original settlor, at death via his/her Will, to re-distribute the remaining assets of the trust amongst the remaining beneficiaries (besides back to the settlor or his/her estate or creditors). The fact that the settlor had “given” the property away to the DING trust, but retained the right to control who ultimately got the money, meant that the gift was not “complete” for gift tax purposes (under Treasury Regulations 25.2511-2(b) and -2(c)) to avoid any gift tax consequences in funding the trust. But the limitation of the power to apply only at death, and only to other beneficiaries (and not back to the settlor), ensured the trust still would not be a grantor trust.

3) State Law Creditor Protection For A Domestic Self-Settled Asset Protection Trust. The key aspect that ultimately made the first DING trust feasible was the introduction in the late 1990s of new state laws that allowed for a so-called “Domestic [self-settled] Asset Protection Trust” (or DAPT for short). Prior to the introduction of the DAPT, any trust that was created by a settlor for his/her benefit would be subject to his/her creditors, and having the settlor’s trust be subject to the settlor’s credits under Treasury Regulation 1.677(a)-1(d) made the trust a grantor trust. When Delaware (and other states, though Delaware popularized the strategy) passed laws permitting a self-settled domestic asset protection trust to enjoy state creditor protection, it was possible for such a trust to NOT be a grantor trust, which in turn introduced the potential to shift state income tax consequences as a DING trust.

Death Of The DING Trust And The Birth Of The NING Nevada Asset Protection Trust

Unfortunately, though the initial DING trust strategy lost momentum after a series of IRS pronouncements – in particular, CCA 201208026 – which declared that while the DING was a valid non-grantor trust, the testamentary power of appointment only ensures that the trust’s remainder was an incomplete gift. The “lead” or income interest in the trust – the share that could be distributed to other beneficiaries while the original settlor was still alive – was deemed to be a completed gift, which would have triggered gift taxes when funding the DING.

The “solution” to this was to give the settlor some kind of lifetime power to recover or control investment assets… except, of course, if the settlor could get access to the trust property while alive, it would become subject to his/her creditors, which in turn would cause the trust to become a grantor trust, invalidating the strategy altogether!

Fortunately, though, while providing the grantor greater lifetime powers created a problem for DING trusts under Delaware law, it was not fatal for similar Incomplete-gift Non-Grantor trusts based in Nevada. The distinction is that under its state laws, Nevada is the only state that provides such robust creditor protection for a domestic trust, that even if the settlor still has some retained powers, it can still be protected – which means the trust can avoid grantor trust status, even as the settlor retains enough control to make the transfer an incomplete gift.

Accordingly, in PLR 201310002, the IRS approved a structure with a Nevada asset protection trust where the settlor retained the power to appoint trust assets to beneficiaries for their Health, Education, Maintenance, and Support (HEMS) – a power that rendered the transfer to the trust an incomplete gift for both the income and remainder interests, but a power that was still eligible for creditor protection under Nevada law and therefore avoided grantor trust status.

The fact that Nevada was the only state to permit this asset protection treatment (necessary to obtain the “favorable” incomplete-gift-plus-non-grantor-trust status) led to the rise of the “NING” trust (based in Nevada) over the prior DING trust (based in Delaware). Notably, now there is also a similar Alaska asset protection trust statute, suggesting that an AING trust may become a potential option/alternative in the future!

Caveats And Concerns Of Using A NING Trust To Reduce State Income Taxes

The first caveat to recognize when seeking to use a NING trust is that it only “works” in scenarios where the trust and the property it owns can completely sever any relationship to the original/home state of the settlor who contributes property to the trust.

In turn, this means that the NING only works for “intangible” property – e.g., investment portfolios of stocks and bonds – and not real estate in the grantor’s home state. The reason is that with real estate and other tangible property, the tax consequences are always tied to where the property is actually physically located. By contrast, intangible property that has no physical presence can’t be evaluated based on where it’s located, and accordingly is taxed based on where its owner is based. Thus, for instance, gains on California real estate will always be taxed in California because it is located there, while a portfolio of stocks/bonds owned by a California resident may cease to be taxed by California if the property becomes attached to a tax-paying entity NOT based in California (e.g., by being transferred from the California resident to a NING!).

Avoiding any relationship to the original/home state also means that the NING trust should have a corporate trustee not based in California (or whatever the home state is), but instead based specifically in the destination state of Nevada. In practice this means finding a Nevada trustee, or Nevada trust company, to handle the NING (though the Nevada trustee could still hire a financial advisor in another state, including the grantor’s home state, to manage the trust assets). And of course, it’s crucial to find an estate planning attorney who is intimately familiar with Nevada state laws to draft the NING properly in the first place!

The second caveat is to remember that when a non-grantor trust actually makes distributions, the tax consequences generally flow through from the trust to the underlying beneficiary (the trust claims a distributable net income [DNI] deduction, and sends a Form K-1 to the beneficiary to report the taxable income on his/her return instead). As a result, this means that as beneficiaries receive distributions, state income taxes may ultimately be due on gains/income passed through to the beneficiary that year. Of course, not all gains may be passed through every year, so some tax deferral may still be facilitated. Nonetheless, it’s important to recognize that some state income tax liabilities may still come through to the beneficiaries if/when/as the NING assets are used.

On the other hand, it’s also important to recognize that if a NING trust is funded and assets are immediately liquidated, and/or if liquidated assets are then immediately distributed, it can draw scrutiny as a potential “step transaction” (where multiple separate steps are taxed as a single event). In other words, if the settlor contributes appreciated stock to a NING, then immediately sells it, and shortly thereafter in the following year distributes all the property back to himself, it’s clear that the NING was just a short-term conduit, and the state tax authorities may claim it should be ignored for tax purposes. As a result, similar to the “backdoor Roth contribution” strategy, it’s necessary to let time pass between each step to substantiate it is not a step transaction (in the context of the NING, some advocate waiting several years between each step, to be safe!).

And the last caveat is simply that some states so dislike the NING strategy as a tax avoidance scheme, that they are outright barring the strategy by changing state tax laws to prevent its use. For instance, in 2014 New York State enacted new laws to prevent the NING strategy, declaring that the trust will be treated as a grantor trust for state tax purposes (even if not under Federal tax law) to ensure that the trust’s income is still taxed in New York. There is some discussion that other states – particularly those with high tax rates, where significant dollars are at stake – may soon follow suit, limiting the potential uses of the strategy. On the other hand, this also creates some time urgency for those who are interested to engage in the strategy sooner rather than later, if their home state hasn’t acted already!

Who Should Use A NING Trust, And When/Why?

The process of creating a NING has some complexity, and a non-trivial cost. A competent attorney must be engaged to draft the trust – which must be done carefully, given that states are becoming increasingly aggressive in challenging the strategy. A conservative settlor may wish to obtain his/her own Private Letter Ruling to ensure the trust will be honored as desired for Federal tax purposes, which under Revenue Procedure 2015-1 entails a cost of $28,300 just for the PLR. And a corporate trustee will have to be hired, and paid on an ongoing basis. Given these dynamics, it will likely take trust assets capable of generating hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars in taxable income for the state income tax savings to be worthwhile.

In addition, the reality is that for Federal tax purposes, the top 39.6% tax bracket for a non-grantor trust - as well as the 3.8% Medicare surtax on investment income – begins at only $12,300 of income in 2015. By contrast, the top tax bracket doesn’t begin until $464,850 for a married couple (with a threshold of $250,000 of AGI for the 3.8% Medicare surtax). As a result, if the NING settlor isn’t already at/near top tax brackets – even beyond the income generated by the assets being contributed to the NING – there’s a danger than any state income tax savings would be more-than-offset by higher Federal taxes instead.

And of course, the NING only presents tax savings opportunities for those who are facing a high state income tax bracket to begin with. Those already in states with little or no state tax rate will not benefit from the strategy. And as noted earlier, some high tax rate states – starting already with New York – are beginning to crack down on the strategy as well.

Accordingly, then, the ideal NING candidate really has three key characteristics:

- Has exposure to significant taxable income from existing intangible assets (e.g., highly appreciated stock, huge portfolio generating ongoing income, etc.), which could be tied up in a NING trust for a period of time without creating other cash flow problems

- Already near or at top Federal tax rates, even after the intangible assets are transferred

- In a state with high state tax rates to be avoided (the actual NING tax planning opportunity)

Nonetheless, for those who fit all of these characteristics, the NING appears to be an especially appealing tax planning strategy to reduce state income tax exposure, particularly to the extent it also blends in as a Nevada asset protection trust strategy (since almost by definition, the Nevada trust that is a NING for state income tax purposes will also be a domestic asset protection trust to qualify for that treatment). At least, until more high-tax-rate states crack down on the strategy to end it altogether!

So what do you think? Have you ever engaged in the NING trust strategy with your high-income clients? Are you considering the strategy now? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!