Executive Summary

This summer, the Financial Planning Association (FPA) announced a new multi-year advocacy goal to pursue legal recognition for the title of "Financial Planner", as a means for bona fide financial planners to distinguish themselves and their services from others (who may use the title but don't actually do financial planning), to help consumers understand who is qualified to provide financial planning advice, and to raise standards for the financial planning profession by tying competency and ethics standards directly to the determination of who can hold out to the public using the title in the first place.

Yet the irony of FPA's new initiative for Title Protection is that "Financial Planner" actually did have protected status as a title all the way back in 2005, when the SEC issued a rule that would allow broker-dealers to offer fee-based brokerage accounts without being required to register as investment advisers and be a fiduciary… and as a part of the rule, stipulated that anyone who held out to the public as a financial planner, delivered a financial plan to a client, or represented that they were providing financial planning advice, would still have to be an RIA fiduciary. But a lawsuit to block the rule ultimately led to it (and the associated Title Protection for "financial planner") being vacated… by the FPA.

In fact, the reality is that in the 15 years since this Title Protection was struck down in the FPA's lawsuit, the organization has actively pursued the opposite strategy of advocating for a uniform fiduciary standard – one that would not separate "financial planners" from others who don't meet the standards to use the title, but instead would simply subject all RIAs and broker-dealers to a single standard. Except in practice, there are many important functions that broker-dealers fulfill that truly are not fiduciary or advice-oriented, such that a uniform standard just isn't feasible. Which has led to both the Department of Labor and Massachusetts implementing uniform fiduciary standards that were both ultimately struck down in court, and the SEC simply refusing to implement a uniform standard at all. Making the FPA's shift to now suddenly advocate for Title Protection a logical – albeit head-spinning – about-face from its position for the past two decades.

At the same time, questions abound as to how the FPA realistically plans to pursue Title Protection, and its noticeable abstention from mentioning the CFP marks anywhere in its discussion of its new advocacy agency, despite the fact that the FPA is the membership association for CFP professionals. The organization's own Bylaws even state that its messaging to the public and the industry should be that "when seeking the advice of a financial planner, the planner should be a CFP professional", and that "anyone holding themselves out as a financial planner should seek the attainment of the CFP mark." Raising the question of whether the FPA is also considering an about-face on its CFP-centricity, too... even as the CFP Board has announced its own Competency Standards Commission to raise their own standards regarding who can use the Certified Financial Planner title?

Ultimately, the FPA has stated that it intentionally has only set a high-level strategic advocacy goal to pursue Title Protection, and that it will spend the next 12-18 months engaging with stakeholders to determine a specific course of action, with no expectation of any legislative efforts earlier than 2024. Which means there is still ample time for the FPA to clarify its intentions and any further swings in its advocacy views. Yet at the same time, the organization's withdrawal from the Financial Planning Coalition, its noticeable exclusion of the CFP marks from its initial positioning statement on Title Protection, its unwillingness to support XY Planning Network's 2021 petition for Title Protection (ironically to reinstate the Title Protection rule that FPA vacated), and its declaration that it intends to enact Title Protection without licensing or regulation (raising the question of how the title could be protected, if no regulator or licensing agency is granted the authority to protect the title?), all suggest that the FPA may already have some plans in place… that it just isn't ready to share yet?

In the end, Title Protection is clearly a laudable goal – one that has been pursued by many industry organizations for years, even if the FPA has only recently arrived at a similar conclusion – and the FPA's willingness to take up the issue is a positive sign, serving as a potential fulfillment of P. Kemp Fain, Jr.'s famous "One Profession, One Designation" call to action. Still, though, the question remains: What exactly is the FPA's plan to pursue Title Protection, will it be able to effectively engage with stakeholders and other organizations that already have established efforts and a vested interest in the outcome, and will it be able to maintain the effort through to fruition in the midst of making 1 and perhaps 2 major about-faces in its advocacy approach?

This past July, the Financial Planning Association announced a new multi-year advocacy objective to pursue legal recognition for the title of "Financial Planner”. In essence, the goal of the objective is that the title of “financial planner” itself would become protected, where individuals would not be permitted to use the title unless they met certain minimum standards. Accordingly, consumers would have greater certainty that if someone says they’re a “financial planner”, they really are one.

Of course, the caveat to enacting title protection for “financial planner” is that some standard of care has to be set for what consumers would expect from someone who is using the title.

For instance, one approach might stipulate that:

If an individual:

- Holds themselves out to the public as a financial planner or as providing financial planning services, or

- Delivers a financial plan to a client, or

- Represents to the client that they’re receiving advice as part of a financial plan or financial planning services…

then that individual is deemed a ‘financial planner’ and must meet the fiduciary standard of care when providing advice to their client.

Under this approach, marketing oneself (i.e., holding out) as a financial planner would trigger a fiduciary standard of care. Delivering a financial plan to a client would also automatically trigger a fiduciary standard of care. And providing recommendations pursuant to a financial plan would trigger a fiduciary standard of care. Thereby protecting the “financial planner” title from salespeople (e.g., brokers and insurance agents), and relegating it solely to those who are actually in the business of financial advice and held to an advice (fiduciary) standard of care.

And notably, the reality is that this kind of standard to protect the “financial planner” title, as FPA is advocating, isn’t a mere hypothetical. The above is from an actual rule that provided Federal protection for the “financial planner” title. But it was sued out of existence. By the FPA.

The Merrill Lynch Rule To Exempt Fee-Based Brokerage Accounts

In 1979, BusinessWeek infamously published its cover story “The Death of Equities: How Inflation is Destroying the Stock Market”. At the time, the Federal Funds rate was on its way to exceeding 20% as Volcker took action to quell inflation, and the Dow Jones Industrial Average was struggling to break 900… a threshold it had first breached in 1965 and had not substantively topped for nearly 14 years.

Yet, as it turned out, the market bottomed just a few years later (in 1982) and, in the subsequent 13 years, went on to a massive boom, pumping out an average annual growth rate of nearly 13% before dividends, and 5×-ing the DJIA from barely 1,000 to over 5,000 by 1995. It was suddenly the era of Wall Street (including the Michael Douglas and Charlie Sheen movie by the same name that declared “Greed, for lack of a better word, is Good”), punctuated by a frightening but quickly recovered crash of 1987 that ultimately just seemed to highlight the market’s new invincibility.

In that environment, retail investors were trading stocks, bonds, and mutual funds like never before. But the internet had not yet arrived. Which meant the only way to buy and sell those investments was to call a broker and pay them a commission to execute the trade on the investor’s behalf. Which, unfortunately, also meant the 1980s and 1990s were the era of record churning (where a broker encourages excessive trading in a customer’s account in order to generate a large volume of trading commissions) by a subset of unscrupulous brokers… and a growing awareness from consumers (due in part to several highly publicized incidents in the media) of the conflicts of interest that existed in the retail brokerage business.

Against this backdrop, then-SEC Chairman Arthur Levitt formed a “Committee on Compensation Practices” in 1994, to be led by Merrill Lynch Chairman Daniel Tully, tasked with evaluating the broker industry’s commission compensation structures and coming up with “best practices” recommendations to reform the system.

The subsequent “Tully report”, issued in 1995, acknowledged that while “the existing commission-based compensation system works remarkably well for the vast majority of investors…”, at the same time, “if the retail brokerage industry were being created today from the ground up, a majority of the Committee that developed this report would not design a compensation system based only on commissions paid for completed transactions.”

In particular, the Committee noted that “opponents of commissions… generally favor a fee-based system of compensation as a way to eliminate potential conflicts of interest” and specifically noted amongst its Best Practices that it was advisable to pay “a portion of [broker] compensation based on client assets in an account, regardless of transaction activity, so the [brokers] receive some compensation even if they advise a client to ‘do nothing’”.

In 1999, the SEC followed up the Tully Report recommendations with a new Proposed Rule entitled “Certain Broker-Dealers Deemed Not To Be Investment Advisers”. Known colloquially as the “Merrill Lynch Rule” (after Tully’s Merrill affiliation), the rule formally granted broker-dealers the ability to offer a new form of “fee-based brokerage account”, where the B/D could charge an ongoing 1% (or similar) fee in lieu of charging commissions in a brokerage account, and as long as the account was non-discretionary and the broker’s advice was still “solely incidental” to the sale of brokerage products, the broker-dealer could collect an ongoing fee without being registered as an investment adviser (which meant the broker-dealer could avoid the RIA’s fiduciary obligation).

From the SEC’s perspective, the proposed Broker-Dealer Exemption was a net positive for consumers to allow brokerage firms to charge fees for brokerage accounts and related advice (and grant them an exemption from RIA status to make it easier for them to do so), in order to reduce their commission incentives for churning. But, in the process, it also drastically blurred the lines between broker-dealers charging fees and RIAs, who also charged fees, when historically, one of the defining distinctions between brokerage firms and RIAs was that the former charged commissions for transactions and the latter charged fees for advice.

Facing the nascent rise of a new crop of online discount brokerages (that were already beginning to compete aggressively against traditional full-service broker-dealer trading commissions), the broker-dealer community quickly adopted the new Broker-Dealer Exemption as proposed and began to roll out fee-based brokerage accounts.

However, the SEC never took action to actually finalize the Broker-Dealer Exemption rule (and address feedback and concerns from certain advocacy groups about the potential impact it would have on consumers’ ability to distinguish between broker-dealers and RIAs), leading the Financial Planning Association to spin off its broker-dealer division (into what is now the Financial Services Institute) to alleviate its own internal conflicts, and then file suit against the SEC’s broker-dealer-friendly rule by claiming it was a violation of the Federal Administrative Procedure Act that the SEC had allowed the proposed rule to take effect without actually completing the rulemaking process to formally finalize it (and acknowledge its critics). In response, the SEC withdrew the proposed rule, re-opened a second public comment period, and then re-issued a “Final Rule” in 2005.

Yet while the Final Rule still largely followed the contours of the original proposed rule, permitting broker-dealers to offer fee-based brokerage accounts as long as their advertising for the accounts “include a prominent statement that the account is a brokerage account and not an advisory account”, and that to the extent the broker provided advice to their brokerage customer that advice would still be “solely incidental” to the brokerage services that the fee was primarily intended to pay for.

However, in a notable concession to the FPA, the SEC’s Final Rule did introduce a new Rule 202(a)(11)-1(b)(2), which stipulated that “a broker-dealer would not be providing advice solely incidental to brokerage if it provides advice as part of a financial plan or in connection with providing planning services and: (i) holds itself out generally to the public as a financial planner or as providing financial planning services; or (ii) delivers to its customer a financial plan; or (iii) represents to the customer that the advice is provided as part of a financial plan or financial planning services.”

In other words, while brokerage firms would be permitted to offer fee-based brokerage accounts without being an RIA (and subject to an RIA’s fiduciary standard), broker-dealers would not be permitted to use the “financial planner” title or otherwise market or deliver financial planning services under the exemption; any financial planning activity would trigger Registered Investment Adviser status, effectively protecting the “financial planner” title as a fiduciary-only service that broker-dealers would no longer be permitted to offer (as brokers).

As a result, the FPA faced a crossroads decision – accept the SEC’s new version of the Rule that would protect the financial planner title but allow brokerage firms to mimic RIA-style AUM fees for (non-discretionary) brokerage account relationships, or challenge the rule to protect the RIA’s ability to charge fees (known as “special compensation” in the Investment Advisers Act of 1940) with the risk that if the lawsuit were to win and the fee-based brokerage rule was vacated, the financial planner Title Protection would be vacated, too.

Ultimately, the FPA chose to protect RIA’s ability to uniquely charge fees over protecting the financial planner title. It proceeded to challenge the 2005 Final Rule in the case of Financial Planning Association v. SEC on the grounds that the SEC exceeded its authority by granting broker-dealers an exemption from the Special Compensation prong (that would otherwise require the receipt of non-commission fee compensation to trigger RIA status), and prevailed. On March 30th of 2007, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals issued its ruling in favor of the FPA, vacating the 2005 Rule’s fee-based brokerage accounts… and its financial planner title protection.

Nerd Note:

As an interesting historical note, the case of FPA vs SEC was decided in a 2-1 split in favor of the FPA, with Judge Brett Kavanaugh – now Supreme Court Justice Kavanaugh – ruling in favor of the FPA that the SEC overreached in trying to permit broker-dealers to charge fees without being fiduciaries, while Judge Merrick Garland – now Attorney General Merrick Garland – as the dissenting vote that felt the SEC had sufficient authority as a regulator to interpret the rule the way that it did.

This is a remarkable shift given the political evolution of the fiduciary rule in the 15 years since, as conservative Republicans (that have supported Justice Kavanaugh) have since objected to expanding the fiduciary rule to broker-dealers providing advice, while Democrats (that have supported Attorney General Garland) have largely supported expanding the fiduciary rule to broker-dealers providing advice!

FPA's Uniform Fiduciary Standard In Lieu Of Title Protection

In the aftermath of the FPA’s successful lawsuit vacating the 2005 Final Rule on fee-based brokerage accounts and financial planner title protection, the SEC proposed a new “Interpretive Rule” to provide clarity to the industry about how to proceed given the sudden void that was created when the 2005 Rule was vacated.

In its 2007 interpretive rule, the SEC declared that it would not re-propose its financial planner title protection (that holding out as a financial planner, or offering or delivering a financial plan or financial planning services, would trigger fiduciary RIA status) and indicated that it would revisit the issue again in the future after the release of the then-pending RAND Study (which had been commissioned by the SEC to further study consumer confusion about the differences between broker-dealers and investment advisers).

More substantively at the time, the SEC’s 2007 interpretive rule also formalized the guidance of the FPA vs SEC court ruling and acknowledged that if a broker-dealer charges an ongoing fee for a brokerage account, it cannot remain a fee-based brokerage account and must instead treat that account as an advisory account (i.e., offer the account not as a broker-dealer but as an RIA, and be subject to RIA standards of care). However, the SEC clarified that the advisor would only be a (fiduciary) RIA with respect to that advisory account, and not with respect to the entire client relationship.

In practice, the outcome of this rule was the birth of the hybrid movement, making it commonplace for brokers to also be affiliated with their broker-dealer’s corporate RIA, such that they could offer brokerage accounts and advisory accounts side-by-side to the same client. As while prior to the FPA’s 2007 lawsuit victory being a dual-registrant was exceptionally rare, within a decade, 90% of all registered representatives at the largest (>$50B of assets) broker-dealers were also dually registered as investment advisers.

However, the sad irony is that as it turned out, FPA’s victory in eliminating fee-based brokerage accounts – and the concern that allowing such arrangements would amplify consumer confusion about the differences between broker-dealers and RIAs when consumers paid ongoing fees for both – ended out amplifying the confusion anyway, as broker-dealers still ended up widely offering commission-based brokerage accounts alongside fee-based advisory accounts as dual-registrants instead. For which consumers still couldn’t tell the difference between when their advisor was acting as a broker and when they were providing service as an actual advisor instead. And the advisor could be operating with either hat while offering services as a financial planner.

Shortly thereafter, the financial crisis of 2008 emerged. And in the wake of the financial crisis, Congress decided to take up legislation to broadly reform the financial system. Which emerged as the next opportunity to reform the regulation of financial planning advice.

But this time around, the FPA took a substantively different tack. Instead of continuing to advocate for financial planner title protection and the resuscitation of that protection from the 2005 Rule, as a part of the Dodd-Frank legislation, the FPA began to advocate for an alternative approach known as the “uniform fiduciary standard”.

The basic concept of the uniform fiduciary standard was that, instead of trying to delineate between broker-dealers and RIAs, or between financial planners and non-financial planners, anyone providing financial advice to retail consumers – regardless of their regulatory channel or planning services – should be subject to a single (unified and uniform) fiduciary standard. In essence, instead of advocating for different (higher) treatment for financial planners, in particular, the FPA advocated that all the channels (regardless of whether they were specifically providing financial planning) should be lifted up to the fiduciary standard.

Yet, while the idea that ‘everyone’ – broker-dealer or RIA, financial planner or not – should be subject to a uniform fiduciary standard was noble in principle, in practice, it was extremely problematic. As the reality is that not every broker actually tries to give financial advice to their customers; some brokers really are ‘just’ brokers engaging in sales transactions with clients. And relative to the entirety of financial advisors, only a small subset are really proactively engaging in financial planning advice (given that there are, even today, only about 90,000 CFP certificants out of 300,000 financial advisors, and barely half that number of CFP certificants out of even more financial advisors 15 years ago).

In other words, not all of the brokerage industry really needs to be subject to a fiduciary standard, because not all of the brokerage industry is giving financial planning (or any substantive financial) advice, and trying to apply a fiduciary standard to all parts of the brokerage industry – instead of just carving out the financial planning advice-givers – is not really feasible.

As a result, while the FPA (and other organizations) advocated for Congress to implement a uniform fiduciary standard under Dodd-Frank, in the end, Congress merely agreed to commission (yet another) study to evaluate whether there was a need to implement a uniform fiduciary standard (known as the Section 913 Study, after Section 913 of Dodd-Frank that authorized it).

And in 2015, the FPA advocated for the Department of Labor to implement its own version of a uniform fiduciary standard on RIAs and broker-dealers providing advice to retirement plans, only to have the brokerage industry challenge the rule and ultimately have it vacated, as the courts agreed that broker-dealers shouldn’t be subject to a fiduciary advice standard because “Stockbrokers and insurance agents are compensated only for completed sales, not on the basis of their pitch to the client. Investment advisers, on the other hand, are paid fees because they ‘render advice’.”

And in 2018, the FPA again advocated for the SEC to apply a uniform fiduciary standard to broker-dealers under Regulation Best Interest, only to have the SEC decline again on the basis that “…adopting a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach [to broker-dealers and investment advisers] would risk reducing investor choice and access to existing products, services, service providers, and payment options…”. Furthermore, the SEC noted in part how the initial implementation of the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule (until it was vacated) had led many brokerage firms to limit their (traditional transactional) brokerage accounts to consumers who didn’t want an advisor and simply wanted to engage a broker.

And in 2019, when Massachusetts proposed its own version of a fiduciary standard that would apply to investment advisers and broker-dealers, the FPA again supported the approach, only to have the rule again vacated as the courts determined that Massachusetts exceeded its authority by trying to expand a fiduciary rule to the practices of broker-dealers that have historically, by common law and prior legislation, been brokerage and not advice activities. In other words, once again, the courts determined that trying to apply a uniform fiduciary rule to the broad scope of brokerage businesses – that at their core have a wide range of ‘traditional’ non-fiduciary brokerage services – is inconsistent with the regulation of broker-dealers.

The cumulative result is that the FPA spent more than a decade repeatedly advocating to eliminate the difference between financial planners and advisors and brokers and RIAs with a single uniform fiduciary rule that has failed in every instance (Dodd-Frank, the Department of Labor, the SEC, and at the state level), while never trying to ask the SEC to take back up its “temporary” withdrawal of financial planner title protection from its 2007 Interpretive Rule. Instead, it was XY Planning Network that submitted a Petition to the SEC in 2021 for the SEC to re-open – and finally finalize – its 2007 Proposed Rule and revisit the issue of title protection. A petition that, notably, the FPA has still never supported.

Which makes it a rather stunning about-face for the FPA, as the organization that ended financial planner title protection in 2007 and refused to take it up for 15 years in pursuit of a uniform fiduciary standard alternative instead, to now declare a multi-year advocacy goal of (re-)enacting Title Protection!

The CFP Marks And The FPA’s (Ambiguous) Plan For Title Protection

In addition to the about-face surprise of the FPA declaring a newfound desire to pursue a Title Protection initiative it previously vacated, there was a second notable about-face in the FPA’s Title Protection announcement: the total lack of any mention of the CFP marks.

As while the FPA declared that Title Protection was important because it would help make the “financial planner” title a differentiator, help consumers identify a qualified financial planner (by whoever is eligible to use the title), and lift standards for financial planning by setting a clear bar for the minimum standards to hold out as a financial planner (relative to today, when anyone with any – or no – qualifications can use the title!)… at no point did the FPA ever suggest that the CFP marks might be that standard. Even though the press release announcing its Title Protection initiative notes that “the Financial Planning Association is the leading membership and trade association for CFP professionals”.

Even more significant, though, is that when it comes to advocating on behalf of CFP professionals, the FPA’s own organizational Bylaws dictate a requirement of CFP-centricity. As a key promise to the leaders of the ICFP when it merged with the IAFP to create the FPA in 2000, as commemorated in a “Memorandum of Intent and Commitment”, and subsequently enshrined in Section 2 (“Purpose”) of the FPA’s Bylaws, is that:

Section 2.1.1. The thrust of FPA’s message to the public will be that everyone needs objective advice to make smart financial decisions and that when seeking the advice of a financial planner, the planner should be a CFP® professional.

Section 2.1.2. The thrust of FPA’s message to the financial services industry will be that all those who support the financial planning process are valued equally as members in FPA and that anyone holding themselves out as a financial planner should seek the attainment of the CFP® mark. FPA will commit to assisting financial planners who are interested in pursuing the CFP® designation.

Section 2.1.3. FPA will proactively advocate the legislative, regulatory, and other interests of financial planning and of CFP® professionals. FPA will encourage input from all of its members in developing its advocacy agenda. It is the intent of FPA not to take a legislative or regulatory advocacy position that is in conflict with the interests of CFP® professionals who hold themselves out to the public as financial planners. [emphasis added]

As the Bylaws clearly state, FPA’s entire Purpose is that when it comes to “financial planner”, the title should be inextricably linked to having the CFP marks as the (minimum) standard for holding out as such.

Which not even the Board of Directors has leeway to change; instead, Section 17.1 (Amendments) of the FPA’s Bylaws explicitly state that “any amendment or repeal of the Organization’s purposes, as outlined in Article II, shall require ratification through an affirmative vote of at least a majority of the individual members of the FPA voting”. Which seems an unlikely membership vote, given that the overwhelming majority of FPA members are CFP professionals themselves (and probably wouldn’t want to see a different standard than the one they’ve already earned as FPA members!).

Of course, the reality is that Title Protection doesn’t have to attach to the CFP marks. In point of fact, the SEC’s prior standard did not; instead, it ‘just’ required that anyone using the financial planner title or offering financial planning services would need to operate as an RIA and be subject to the attendant fiduciary standard (without explicitly stipulating any required credentials upfront, as long as the advisor adheres to the fiduciary standard with respect to their financial planning advice itself).

At this point, the FPA has simply stated, “In the coming months, FPA leaders will engage Members, partners, allied organizations, and other groups on the Association’s goal of title protection and explore the many potential strategies FPA may pursue… Our work in the months ahead, charting our course and identifying the minimum standards for anyone calling themselves a financial planner, will be critical to this endeavor.” Which suggests the organization may simply be trying to ‘leave its options open’.

Nonetheless, when the FPA is the membership association for CFP professionals, and couldn’t move away from a CFP-centric focus to financial planner Title Protection without a vote of the general membership anyway, it’s difficult to understand why the FPA wouldn’t, by default, be fully embracing the CFP marks as the standard for financial planner Title Protection (at least until/unless its stakeholder input process from members surfaces some other preference)?

As ultimately, the FPA could really only take one of three paths in setting a competency standard for Title Protection relative to the CFP marks:

- The FPA could advocate for a Title Protection standard that is different than the CFP marks… but doing so would go against its Bylaws and the overwhelming majority of what its own membership has staked as the designation of choice;

- The FPA could advocate for a Title Protection standard that is lower than the CFP marks… but that again would go against its Bylaws (and given the history of other ‘CFP Lite’ initiatives, risk a severe backlash from its members); or

- The FPA could advocate for a Title Protection standard that is higher than the CFP marks… but doing so would literally mean many of its own members, who hold the CFP marks, couldn’t call themselves a “financial planner”, which doesn’t seem realistic.

Which simply raises the question again: Why has the FPA not fully and vocally supported the designation that sits at the center of the organization’s founding intent, Bylaws, and membership majority?

What Is FPA’s Plan From Here?

To the extent that the FPA is trying, under new leadership, to re-assert its value proposition in the marketplace – of which Advocacy is one of the FPA’s four P-L-A-N (Practice support, Learning, Advocacy, and Networking) value pillars – it’s not unreasonable for the organization to state a high-level advocacy intent of where it wants to focus in the coming years… and then to figure the specific tactics it will pursue to achieve that strategic goal. Which appears to be the path FPA is pursuing, as leadership has gone out of its way to emphasize, “the next 12 to 18 months will be used to figure out what the competencies and standards should be,” and that they “don’t expect… to introduce any legislation until 2024”.

Nonetheless, the concern remains that the FPA already has formulated behind the scenes at least some portion of an agenda that it intends to pursue.

The first indicator is how the organization has gone out of its way to not mention the CFP marks at any point when discussing Title Protection. Which raises the question of whether it is seriously contemplating the decision that even members who have the CFP marks couldn’t call themselves a “financial planner” unless they meet some higher standard… or are considering whether to include other designations to qualify for Title Protection in addition to the CFP marks?

Other designations are a fair consideration, given that arguably, there are at least a few other ‘reasonably credible’ designations. However, CFP Board already offers “Challenge Status” to most other major designations (which means those with other designations could fairly readily obtain the CFP marks). And notably, Canada pursued a similar multi-designation path for its “financial planner” Title Protection in recent years; the end result was that once the door opened to multiple designations, the industry’s product sales firms made a brand new designation (that was much easier to get than the CFP marks and amounted to little more than just taking the minimum licensing exams to be a salesperson in the first place), persuaded regulators to include it as one of several designations to qualify for the title, and effectively dragged down the Title Protection standards by opening the door in the first place!

On the other hand, if the FPA’s vision is to lift competency standards to call oneself a “financial planner” to be higher than the current standard of the CFP marks, why propose a new form of Title Protection with a new standard, versus simply attaching to the CFP marks and then advocating to the CFP Board to lift their own standards? An initiative that, ironically, the CFP Board appears to already be undertaking itself (without the FPA?) with its recently announced Competency Standards Commission!

The second indicator is the FPA’s decision to leave the Financial Planning Coalition at the end of 2022, at the exact moment it is embarking on a major new advocacy initiative. Which is normally when the organization would most likely need to rely on its Coalition partners… unless it already plans to pursue a course of action that it knows those partners, namely NAPFA and CFP Board, won’t support? Otherwise, why not stay partnered with CFP Board, which in practice has been the de facto standard setter of what it means to be a (Certified) Financial Planner (literally writing the Code of Ethics and Standards of Conduct for CFP professionals), and has materially increased its own standards twice over the past 15 years?

Granted, some advocates for the profession – including yours truly – have at times urged CFP Board to lift its standards even further. But the reality is that the industry, in the aggregate, can only adjust so far, so quickly, and CFP Board has actually done an admirable job of lifting the standards without losing CFP certificants along the way (which ensures that when the standards are lifted, those CFP certificants will follow the new higher standard!).

If the FPA wants to move the standards further and faster than CFP Board, is it ready to lose a material segment of its membership – who may themselves not meet the new standard? And if the FPA doesn’t want to move the standards further and faster than CFP Board… why not simply support CFP Board as it begins its new Competency Standards Commission? Wouldn’t it be far more expeditious to lift standards for financial planners by driving up the standards that apply to the 90,000+ advisors who already have the marks and adhere to the CFP Board’s requirements, than to impose an entirely new regulatory regime to license the title alongside?

Especially since when it comes to protecting the title itself, while the FPA has repeatedly declined to pursue Title Protection since it vacated the original protection in the 2005 Rule and only recently made an about-face on the issue, other organizations have already long carried the torch for Title Protection. In addition to the fact that CFP Board’s own designation is implicitly a form of title protection – albeit for the Certified Financial Planner title – for which it outright owns the trademark and has a multi-decade track record of proactively protecting the title.

In turn, it was XY Planning Network that advocated for Title Reform in Regulation Best Interest (which ultimately did at least limit standalone brokers from using the “financial advisor” title!), and also sued the SEC to block Reg BI’s permissiveness in allowing dual registrants to switch hats instead of separating sales from advice, and advocated against Massachusetts’ ill-fated uniform fiduciary rule in favor of Title Protection instead, and filed a petition with the SEC to re-propose the Title Protection rule that FPA struck down. What plan does FPA have that entails not working with or supporting any of the other organizations that have already fought for Title Protection for years?

Perhaps most curious, though, is FPA’s emphasis that it plans to pursue Title Protection that “will establish minimum standards for financial planners without creating an unnecessary regulatory burden for those meeting the standards…” [emphasis added] and has further stated that “we’re not touching licensing, we’re not touching regulation… this is just documenting, wherever we need to, the phrase ‘financial planner’ and giving it the title and protection it deserves.”

Which sounds like a lovely goal, but almost by definition, Title Protection means some regulator has to enforce whatever the deemed standards are to use the “financial planner” title and dole out consequences to those who violate the standard. Otherwise, the title isn’t actually protected. If FPA already has a plan for how this can be accomplished, without licensure or regulation… then it would seem that FPA already has a plan after all?

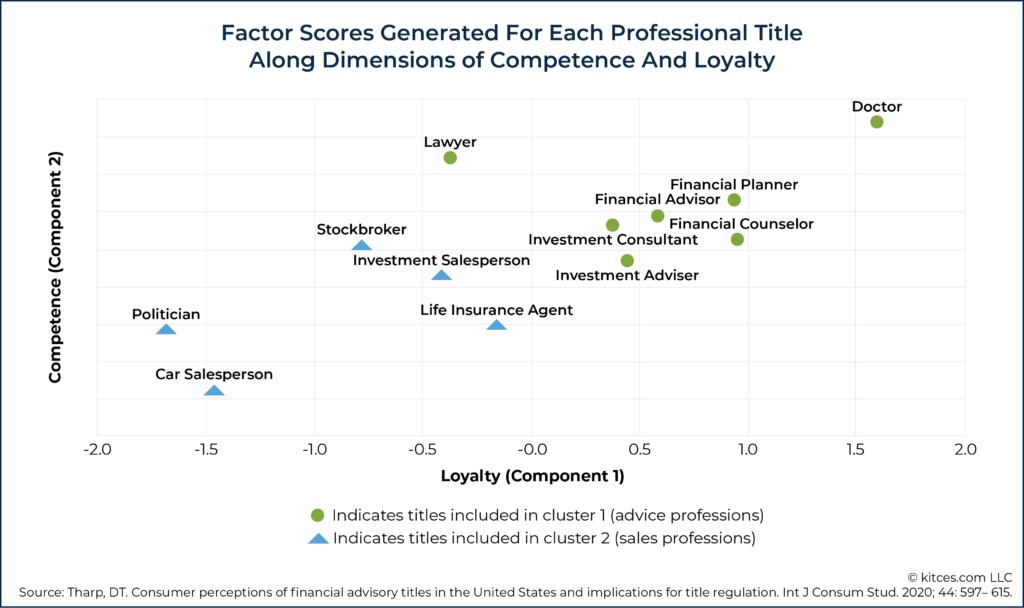

And ultimately, these dynamics matter… because the industry has long since proven that the “financial planner” title is very effective at engendering trust with consumers and helping to facilitate the sale of brokerage (and insurance) products. In fact, research shows that “financial planner” is already the highest-trust title that advisors use!

Which means the industry is not going to simply walk away and relinquish the use of a ‘lucrative’ marketing title without a fight. And it has significantly more resources to deploy, as, by revenue, the Financial Services Institute (which lobbies for independent broker-dealers) and NAIFA (which lobbies for insurance companies) are both larger than the FPA, and SIFMA (which lobbies for large broker-dealers) is nearly twice the size of all the others combined. And the Political Action Committees (PACs) of FSI and SIFMA are 2X to 4X what the FPA does to fund their direct lobbying efforts… while NAIFA’s PAC is more than double the rest of them combined to fund lobbyists that will oppose higher standards that their life insurance agents may not qualify for!

As a result, the best-case scenario is that FPA will be fighting a battle against opponents that massively outfund them. Which makes the clarity of their plan, its defensibility against others who may want to lessen the standards, and the depth and breadth of their Coalition especially crucial in order to actually be able to execute successfully (and not just open a Pandora’s Box that it will regret once it’s too late to close).

In point of fact, this is ultimately why industry pioneer P. Kemp Fain, Jr. – after whom the FPA itself named its pinnacle lifetime achievement award – set forth the mantra nearly 35 years ago: One Profession, One Designation. It was a recognition that there are multiple stakeholders in the financial planning profession, along with multiple designations, but ultimately the hallmark of a recognized profession is having a single clear pathway to determine ‘professional’ status, and that a key element of that is to have a title, license, or other marks to connote to the public who has achieved that professional status.

For which CFP Board (then the IBCFP) is uniquely positioned as the established owner of the Certified Financial Planner trademark – which means they already have the legal right to control the title. And the stakeholders in the profession can come together to create pathways for those who don’t have the CFP marks to earn them (or challenge the exam!) and take the steps over time to lift those standards further (as Fain himself advocated).

In theory, the FPA has an opportunity to fulfill the vision of P. Kemp Fain, Jr. And its own unfinished business after vacating financial planner title protection in 2005. But can the FPA establish a viable plan on its own? Can it earn the trust of stakeholders after two major about-faces in recent years? Will it finally begin to work with the organizations that have carried the banner of Title Protection and of lifting standards over the past 15 years for the betterment of the profession?

At this point, it seems that only time – for the FPA to formulate, or at least to be more public about, its plan – will tell?