Executive Summary

Harvesting capital losses to generate a current tax savings is popular. So popular, in fact, that not long after the US income tax was first created a century ago, the strategy was rapidly adopted as a tax savings technique and became a perceived tax abuse. In turn, this lead to the establishment of one of the first pieces of legislation to close an “abusive” tax loophole, and we now know Congress’ solution as the “wash sale” rules.

Yet the challenge of the wash sale rules is that the requirement not to own a “substantially identical” stock or bond within the 61-day wash sale period was rather straightforward to apply in its day, but has become outdated given the rise of pooled investment vehicles like mutual funds, and especially with the explosion of index ETFs. Now, taxpayers face oddly disparate treatment, where it’s not permitted to harvest the loss on a stock that’s down and replace with the same stock, but it’s “fine” to harvest the loss on a mutual fund that’s down and replace it with another mutual fund that owns overlapping securities.

Ultimately, the spirit of the wash sale rules was that investors should be required to endure some “tracking error” risk with the replacement security owned during the wash sale period… which means swapping ETFs with a 0.99+ correlation to harvest a loss without any risk of a performance difference almost certainly violates Congressional intent. And while it remains to be seen whether the IRS will become more aggressive in pursuing the issue, and/or whether Congress will attack this abusive “tax loophole” once again, the fact that there has been no action to limit the abuses yet does not protect taxpayers who are in clear violation of the spirit and intent of the rules in the first place. So investors should at least be cautious to consider how far they push the limits with tax loss harvesting (TLH) of mutual funds and ETFs.

Understanding the Wash Sale Rules On Tax Loss Harvesting (TLH)

The so-called “wash sale” rules are one of the oldest anti-abuse provisions of the Internal Revenue Code, first originating with the Revenue Act of 1921, and substantively codified in the current IRC Section 1091 as a part of the general overhaul in developing the Internal Revenue Code of 1954.

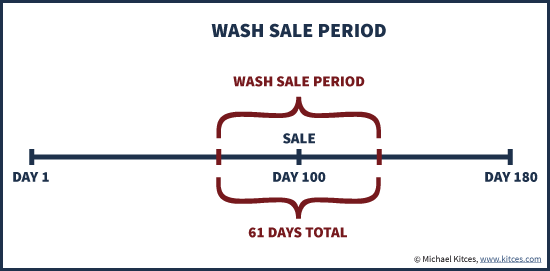

The basic concept of the wash-sale rule is relatively straightforward – its purpose is to limit someone from Tax Loss Harvesting (TLH) by just selling an investment for a tax loss and immediately buying it back again, which could otherwise result in tax savings (in the form of a deductible loss) without the investor substantively changing his/her economic position at the end of the day. Thus, to the extent the investor has purchased a stock within 30 days before or after a sale that recognized a loss, the purchase within that 61-day period causes the otherwise-deductible loss to be a wash.

In other words, when the wash sale rules are triggered, any harvested tax losses from the original sale are no longer deductible. Instead, the disallowed loss is added onto the cost basis of the replacement security (which essentially means its value will not be received until a subsequent sale in the future), which is automatically tracked by custodians if the securities are held in the same account under the recent new required cost basis reporting rules for custodians. In addition, the holding period of the new investment (i.e., to determine eligibility for long-term capital gains treatment) will include the holding period of the original investment sold at a loss.

Example. You purchased 1,000 shares of XYZ stock for $80/share back in February of 2013. On March 3rd of this year (2015), you sell the stock for $62, recognizing an $18/share (or $18,000 loss). Later that week, the stock rebounds to $66, and you buy it back a week later at $67/share on March 9th. Because the purchase occurred within 30 days of the sale, the original $18/share loss is no longer deductible. However, the newly purchased stock will now have a cost basis of $67 (purchase price) + $18 (wash sale loss) = $85/share.

Given this treatment, if the stock is later sold for $67, the $18/share loss will again ultimately be recognized; the loss was simply held in abeyance. Alternatively, if the investment is held until it appreciates above $85/share, that $18/share price increase will not be taxable, effectively having been offset by the wash sale loss. (However, if the wash sale rules are triggered because the replacement investment is purchased inside a retirement account, the tax deduction for the loss may be permanently lost!)

Notably, the new shares purchased at $67/share will also immediately be eligible for long-term capital gains rates, as the 25-month holding period from the original stock is automatically “tacked on” to the replacement purchase.

A key aspect of the wash sale rules is that they are only triggered when the investor buys back a “substantially identical” investment to the one that was sold for a loss (and/or a contract or option to buy the investment again). Thus, for instance, selling Ford and buying back Ford (or Ford call options) would trigger the rules, but selling Ford and buying GM, or selling Dell and buying Hewlett-Packard (same industry but clearly a different company) would be in the clear.

Of course, buying a substantively different investment – at least for the wash sale period – introduces the “risk” that the new investment will not generate the same performance as the original one during what is effectively a 31-day waiting period. But ultimately, that’s actually the point of the wash sale rules. Congress will allow an investor to "harvest" the loss and subsequently own the investment again, as long as the investor puts themselves at substantive risk of at least one month’s worth of tracking error; alternatively, this also means that it’s not even worth harvesting a tax loss unless the potential tax deferral benefit of the loss outweighs the risk of tracking error during the intervening time period.

The Wash Sale Problem And “Substantially Identical” Mutual Funds

In the context of individual stocks and bonds, the application of the wash sale rules and what constitutes a “substantially identical” security is fairly well established. Stocks of different corporations are not substantially identical, nor are bonds substantially identical if they have different issuers, and of course securities are not substantially identical if their underlying provisions differ (e.g., different interest rates or maturity dates). However, the requirement to trigger wash sale rules is not that they be precisely identical, merely that they be substantially identical. Thus, for instance, IRS Publication 550 still notes that different corporations may be substantially identical if they’re predecessor and successor corporations of a reorganization, and preferred and common stock can still be substantially identical if the former is convertible into the latter and they have the same voting rights and dividend restrictions (and trade at prices similar to the conversion ratio).

When it comes to mutual funds, though, the situation is murkier. Strictly speaking, the origin of the wash sale rules predates the first (open-ended) mutual fund, though with the passage of nearly 90 years since both have been in effect, there has still been remarkably little clarification on the issue. In former IRS Publication 564, the Service acknowledged that “ordinarily, shares issued by one mutual fund are not considered to be substantially identical to shares issued by another mutual fund”, but without any clarification as to what circumstances two mutual funds could be substantially identical.

The wash sale issue in the context of mutual funds is the fact that ultimately, a mutual fund is a pooled investment vehicle for the underlying stocks, bonds, or other securities, and in the end the mutual fund only declines in value because of losses on its underlying securities. Which means a tax loss harvesting sale of a mutual fund and switching to another replacement fund isn’t actually about harvesting the loss of the mutual fund itself, per se, but the losses on the underlying securities. Even though the reality is that the replacement fund could actually be holding those exact same loss securities.

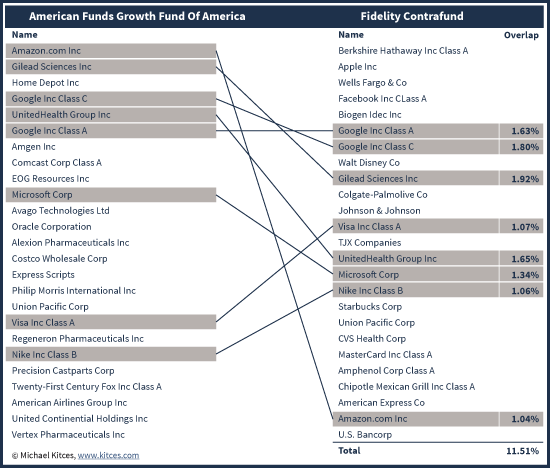

For instance, consider two of the largest actively managed mutual funds out there today: American Funds’ Growth Fund of America (AGTHX), and the Fidelity Contrafund (FCNTX). The two funds would “easily” be considered substantively different mutual funds. Yet a deeper look of the underlying holdings reveals that amongst the top-25 holdings alone, almost 1/3rd of the securities are overlapping, accounting for almost 12% of the funds’ assets. And that’s just amongst the top-25 holdings!

In fact, the sheer amount of overlap in the funds leads to remarkably similar investment performance as well; the cumulative returns for the two funds are shown below over the past 10 years. While cumulatively the funds have exhibited a significant compound difference, the correlation of their daily price changes is a whopping 0.93!

Data from YCharts

Given the incredibly high correlation between these two funds, the grounds for calling them “not identical” arguably begins to break down. Not only does the substantive overlap in their securities lead to remarkably similar price returns – especially over periods as “short” as a 30-day wash sale period – but the reality is that big losses in just a few stocks could drive down the price of the whole mutual fund, which means selling one and replacing with the other could literally be replacing the exact stocks that were down with identical stocks held in another fund.

In other words, if a loss in Growth Fund of America was triggered by a big decline in the tech sector stocks like Amazon, Google, and Microsoft (overlapping holdings in both) while the rest of the market was flat, and the investor sold for a loss and replaced it with Contrafund, the investor would replace the exact stocks that were down with the identical replacement stocks and still claim the loss! Even though the reality is that if the investor held the underlying stocks directly, harvesting those losses could still be done (on a stock-by-stock basis, leading to even more loss harvesting opportunities), but the replacement securities to avoid the wash sale would actually have to be different stocks, not the same stocks just held within a different pooled mutual fund wrapper!

Wash Sales With Substantially Identical ETFs

Over the years, the IRS has not pursued wash sale abuses against mutual funds, perhaps because it just wasn’t very feasible to crack down on them, or perhaps because it just wasn’t perceived as that big of an abuse. After all, while the rules might allow you to loss-harvest a particular stock you couldn’t have otherwise, it also limits you from harvesting ANY losses if the overall fund is up in the aggregate, since losses on individual stocks can’t pass through to the mutual fund shareholders. Ironically, this is actually why Indexing 2.0 solutions are becoming popular.

However, at least with mutual funds, the funds could and often were managed in a substantively different manner. While large diversified mutual funds often have a big chunk of overlap, there are clearly at least some differences in the underlying stocks, as well as the manner by which the manager buys and sells those stocks over time. Given these differences, and what at least was usually just “limited” overlap, mutual funds have kept their “ordinarily not substantially identical” treatment.

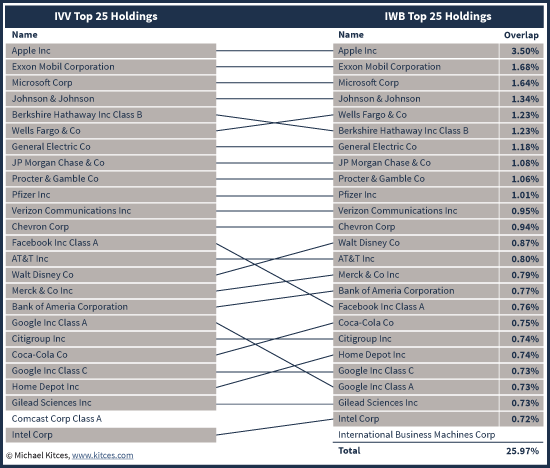

With ETFs, though, the situation gets much murkier, as nominally different ETF funds and even ETF providers may in the end be mimicking the exact same underlying index and basket of stocks. For instance, swapping from SPY (the State Street S&P 500 index fund) to IVV (the iShares version of the same index fund) is a different fund manager with a different expense ratio that may execute the underlying mechanics slightly differently, but in the end is tracking the exact same index, owning virtually (substantively!?) identical stocks, and thus is arguably the “same” and runs afoul of the wash-sale rules. In a world of active (non-index) mutual funds, this was never an issue; fund managers might have ‘similar’ views and hold ‘similar’ stocks, but they weren’t by design holding the same stocks with the same target allocation. But that was true with index mutual funds. And while the sheer size of index funds limited the impact in the past – 15 years ago in 2000, Vanguard had just over $500B AUM total across all of its funds – indexing has exploded in recent years, with S&P 500 index ETFs SPY, IVV, and VOO alone accounting for nearly $300B of AUM (and the ETF industry overall approaching $2 trillion of AUM).

And while arguably swapping from index funds like SPY to IVV are almost certainly a wash sale abuse (or at least, a transaction that should trigger the wash sale rules), what about situations like swapping from the S&P 500 to the S&P 100 (e.g., from IVV to OEF). To some extent, these are “different” index funds… except the reality is that any losses driven by the top 100 stocks in IVV will by definition by held in the replace OEF fund, overall almost 2/3rds of the S&P 500 is made up of the stocks in the S&P 100 anyway, and the two exhibit a whopping 0.983 correlation on their daily price returns over the past decade!

Data from YCharts

In fact, even switching index providers doesn’t actually yield much of a difference. For instance, going from the S&P 500 to the Russell 1000 (or from IVV to IWB) may sound like different index funds with different companies built in a different way… except their top holdings really are ‘substantially’ identical, and the only difference in their top-25 holdings at all is that the Russell 1000 replaces Comcast with IBM in the #24 and #25 spots. Over the past decade, their daily price changes had a whopping 0.991 correlation!

In fact, because the performance of large-cap stocks is so dominating in cap-weighted index funds, IVV actually has a 0.989 correlation to the Vanguard Total Stock Market fund (VTI) as well. Unless the fund is extremely constrained – e.g., by some non-traditional weighting approach, or perhaps narrowly confined to a particular industry or sector – a huge portion of “different” ETFs based on differently-constructed indexes or from different providers still end out with extremely similar performance tracking, especially over time periods as “short” as a 30-day wash sale period.

Where Is The Line On “Substantially Identical” And Wash-Sale Rule Abuse?

In the end, the problem with the wash sale rules – at least as currently written – is that they simply were not intended for a world of pooled investment vehicles. In the context of individual stocks and bonds, the rules are fairly straightforward to apply, and the determination of what constitutes “substantially identical” can be made by simply looking at the characteristics of the stock or bond itself. But when it comes to mutual funds and ETFs, looking at the construction of the underlying investments is just not as practical.

For instance, with two funds that “just” overlap by 70% in their underlying holdings, how do you determine whether they are substantially identical or not? Is there a threshold where the rules would apply (must have 50%, or 75%, or 90% overlap?)? Does it matter (or not) whether the losses being harvested are attributable to the 70% of overlapping stocks, or the “other” 30%, and is there an easy way to figure this out?

And as shown earlier, the problem is not merely hypothetical. A large number of common mutual funds and ETFs really do have incredibly high levels of overlap and “near perfect” correlations in daily performance, suggesting that even if a “slightly” different index (e.g., S&P 500 vs S&P 100) or “slightly” different provider (e.g., S&P 500 vs Russell 1000) are being used, it’s hard to see how the ETFs are not substantially identical. It crops up in regular practice for advisors, and “robo-advisors” like Wealthfront and Betterment run into the same issues in their efforts to automate their loss harvesting and use of (not substantially identical) replacement securities.

Ultimately, there will no doubt be a large number of “grey” and murky situations, but I suspect that until the IRS provides better guidance (or Congress rewrites/updates the wash sale rules altogether!), in the near term the easiest “red flag” warning is simply to look at the correlation between the original investment being loss-harvested, and the replacement security; at correlations above 0.95, and especially at 0.99+, it’s difficult to argue that the securities are not ”substantially identical” to each other in performance.

Of course, the common goal of finding “good” replacement securities when doing tax loss harvesting is specifically to find those that have the lowest possible “tracking error” in anticipated performance relative to the original security… yet the whole origin and purpose of the wash sale rules is to ensure that tracking error is present, so there is a risk/return trade-off to be considered any time you harvest a loss. In other words, if you believe you’ve found a replacement investment that removes any danger of a material difference in performance during the wash sale period, you’ve probably just defined for yourself what constitutes a “substantially identical” security that would violate the wash sale rules! Alternatively, if the replacement security does present a less-than-near-perfect correlation to the original one being loss-harvested, then it should pass muster with the wash sale rules… but you’ll still have to decide if the (tracking error) risk is worth the tax-deferral (not tax avoidance!) value of harvesting the loss in the first place.

Unfortunately, the say on “substantially identical” is determined by the IRS, and when they send a nasty gram disallowing capital losses claimed on a tax return, it’s simply too late to do anything other than decide if the definition is worth fighting in tax court. I suspect legal fees will drastically outweigh the value of the deduction in almost all cases.

There is a “substantially similar” standard laid out that uses a 70% overlap as the dividing line. You can’t be identical if you aren’t at least similar so this is an easier test to flunk. Therefore we’ve felt that if you have a less than 70% overlap you shouldn’t have to worry about wash sales. Above 70%there is no bright line test.

Bob are there any tax cases or IRS rulings to support this 70% test? I have been looking for anything official involving mutual funds and wash sales but other than former IRS publication 564 I’ve been relatively unsuccessful. I was wondering if you could point me in the right direction?

There is a “substantially similar standard” that uses 70%. Our thinking is if you aren’t substantially similar you certainly can’t be substantially identical.

It is in the straddle rules.

Really very helpful blog.Thanks for sharing nice information on your blog.Mutual Fund Holdings

I was just wondering if you know if capital losses can be still claimed from a mutual funds loss sale if you happen to repurchase the same mutual funds that you may have sold within a 30 day period. Is there a tax rule called a wash sale that will disallow the capital loss deduction when filing taxes later if you repurchase the same funds within a 30 day period? I read a little on this and wondered if it applied in my case with mutual funds.

Your information is welcomed and appreciated

Joseph,

Yes, mutual funds and ETFs are subject to the exact same wash sale rules as any other investment, where the loss is disallowed if you buy an identical replacement investment during the wash sale period.

– Michael

Hi,

was wondering if its worth doing a tax loss sale but not replacing it with anything? i know i still get the tax deduction and the amount saved = loss * tax rate is not reinvested in anything.

can you explain the mechanics of replacing an investment vs just taking the loss with no replacement.

thanks!

Does “substantially identical” mean same fund same number of shares, or same fund any number of shares? If I get a capital gains dividend that is automatically reinvested and then within 30 days liquidate the fund holdings at a loss that is larger than simply selling the shares received as a result of the dividend reinvestment, can I claim the loss on the shares that exceed those received as a result of the reinvestment? My understanding is that the wash sale of just the LTCG shares adjusts the basis of the remaining holdings. How does it work when you have some lots that yield gains and some that yield losses after you have disposed of the original dividend shares in a wash sale? Can I apply the wash sale loss to lots of my choice or do I have to allocate them in any particular way?

The law explicitly says “substantially identical stock or securities”. In my opinion this relates to the nature of the stock/security, but not the performance. Hence I find your correlation argument interesting….

How about two companies stocks perform identical? (hard to find in the real world)

Would you consider that a wash sale too?

What if you sell a mutual fund purchased at various cost basis? the overall sale is a profit but a handful of the shares in the lot are higher than the sale price?