Executive Summary

Welcome to the September 2024 issue of the Latest News in Financial #AdvisorTech – where we look at the big news, announcements, and underlying trends and developments that are emerging in the world of technology solutions for financial advisors!

This month's edition kicks off with the news that Fidelity has announced a new bundled technology offering for advisors, including its own Wealthscape brokerage and eMoney financial planning software, alongside Advyzon's portfolio management and performance reporting platform – which is rather surprising given that Wealthscape itself was once advertised as an "all-in-one" solution that could replace third party portfolio management software like Advyzon, and suggests that Fidelity's aspirations for (and massive investment into) Wealthscape as a core software offering that would make its custodial platform 'stickier' for advisors and their assets may have been upended by advisors' preferences to use independent standalone software instead?

From there, the latest highlights also feature a number of other interesting advisor technology announcements, including:

- GeoWealth has announced an $18 million investment from BlackRock to enhance GeoWealth's capabilities for offering customized investment models (such as those provided by BlackRock itself) – which raises questions about whether BlackRock's ownership stake in one of its own distribution channels will cause conflicts if BlackRock products are favored on the platform at the expense of other asset managers, or if BlackRock is content to invest passively in GeoWealth (since as long as BlackRock sees some share of the assets on GeoWealth's platform, it will benefit as long as the TAMP continues to grow)?

- Estate planning software provider Vanilla has announced an estimated $20 million capital raise as it builds out its estate document preparation service on top of its existing estate analysis tools, reflecting investors' enthusiasm for the growth potential for software tools that can also be packaged as a service (and priced accordingly higher) – although the question remains whether there will actually be enough demand for estate planning documents to sustain the service, given that clients only update their estate documents every 5–10 years (at most)?

- Hearsay, the social media marketing and compliance platform for financial professionals, has announced that it is being sold to Yext for $125 million, 11 years after being valued at $171 million – highlighting how even becoming a largely successful AdvisorTech provider (as Hearsay's 260,000 users and $60 million in revenue attest) wasn't necessarily enough to live up to the expectations of everyone who expected social media to be the dominant channel for advisor marketing.

Read the analysis about these announcements in this month’s column, and a discussion of more trends in advisor technology, including:

- Wealthtender, a platform for gathering client reviews and testimonials, has partnered with the AI-powered compliance provider Hadrius to allow advisors to scan all testimonials collected through Wealthtender for compliance with the SEC's Marketing Rule, and flag potential violations for human review – which represents a way to harness AI for a function that it truly does well in reading large amounts of text and flagging passages with specific meanings and implications, although given the relative infrequency that testimonials actually come in, there might not be that much time savings.

- Morgan Stanley has become one of the first financial services firms to launch its own internal AI meeting notes tool, which highlights the unique opportunity that mega-firms like Morgan Stanley have (with the reams of internal data at their disposal) to build their own in-house AI tools without the potential for exposing client data to a third-party vendor.

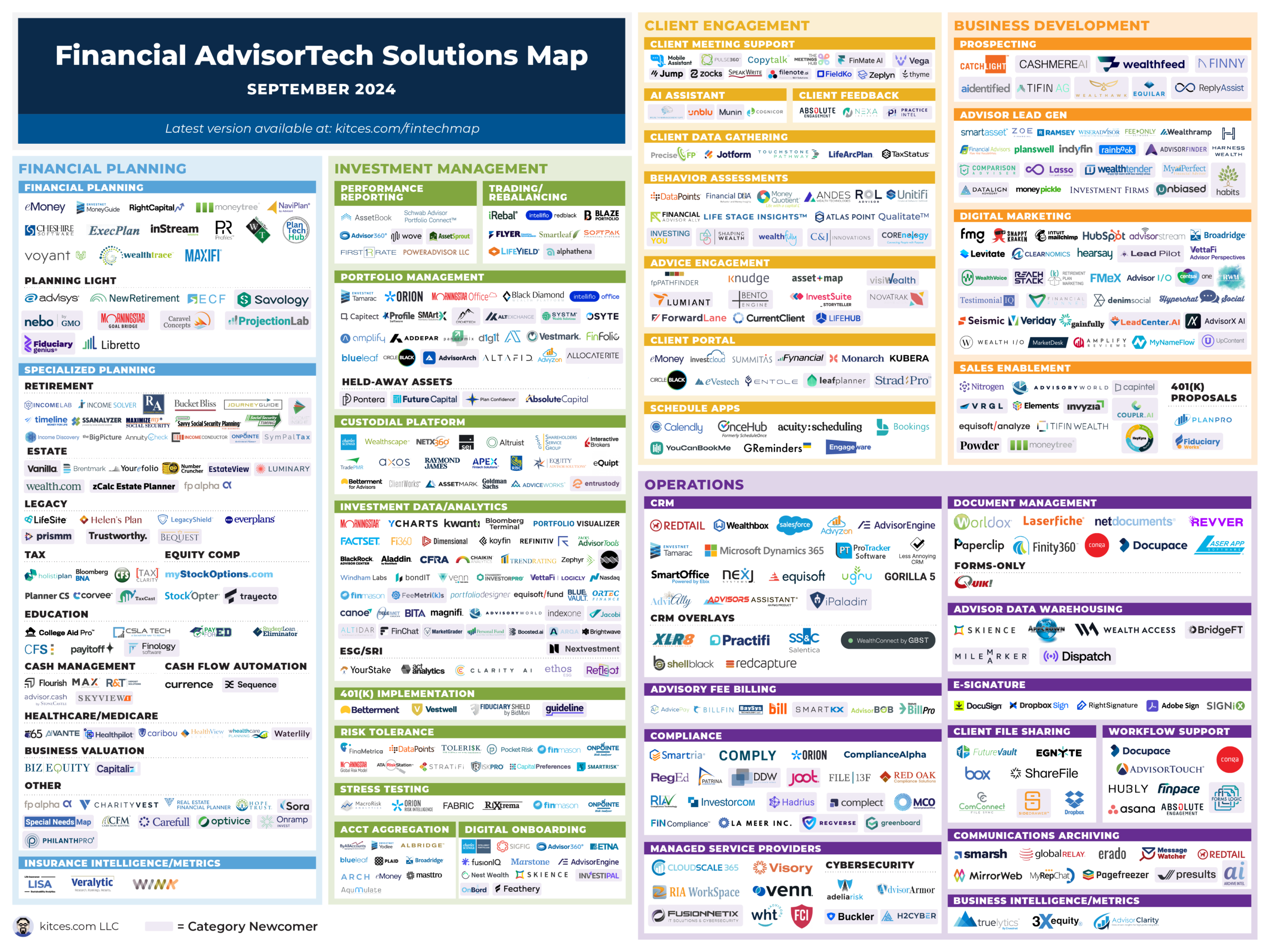

And be certain to read to the end, where we have provided an update to our popular "Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map" (and also added the changes to our AdvisorTech Directory) as well!

*And for #AdvisorTech companies who want to submit their tech announcements for consideration in future issues, please submit to [email protected]!

Fidelity Announces A New "All-In-One" Tech Bundle… But Is It Actually Just Unbundling Its Own All-In-One Solution?

While the financial advice industry has long debated the merits of using a single all-in-one software platform versus various individual "best-of-breed" solutions, RIA custodians have historically had an interest in seeing only one of these options playing out: Namely, an all-in-one platform, ideally (from the custodian’s perspective) built around the custodian's own technology "hub". It's easy to see why that makes business sense for the custodian: The more deeply the custodian's technology (in practice, usually portfolio management and performance reporting tools) can be embedded into the advisor's tech stack, the more disruptive it would be for the advisor to leave, which means the 'stickier' that advisor – and their clients' assets – become for the custodian, ensuring their continued business and revenue stream.

The caveat, however, is that when the primary reason for a custodial platform to offer technology isn't the technology itself but rather to make it easier to retain client assets, it creates a fundamental tension in the allocation of the firm's resources to technology versus other areas that are more central to their actual custodial business. Which ultimately can make it harder for the custodian to build and sustain technology that's competitive with standalone software companies for whom building good technology really is their core competency. And so the pendulum has swung back and forth over the years between custodians trying to build (or buy) their own all-in-one portfolio management and performance reporting systems, and then backing off to focus on other initiatives. A prime example of this being Charles Schwab buying PortfolioCenter as a multi-custodian portfolio management platform in 2010 before selling it and pivoting towards third-party integrations (and its own Schwab-only PortfolioConnect system) a decade later.

Another example of a custodian building its way towards an all-in-one solution, ostensibly in the hopes of better attracting and retaining advisors to its core custodial offering, was Fidelity's Wealthscape platform. Launched in 2016 to great fanfare, Fidelity promised that it would obviate the need for traditional third-party portfolio management software with its deep integration with Fidelity's systems and competitive price point compared to independent tools at the time. Fidelity purported to allocate several hundred staffers to Wealthscape's initial development, with a planned total of over 1,000, all of which would add up to a substantial portion of their purported $2.5 billion technology budget – all with the goal not of making a profitable standalone software product, but of making one that would make its advisor relationships sticky enough to realize a potentially huge return on the massive investment through more revenue growth on its custodial assets.

It comes as a rather great surprise, then, that this month Fidelity has announced it is offering an "all-in-one tech stack" bundling together not only Fidelity products such as eMoney and Wealthscape, but also a third party portfolio management tool in Advyzon. In its announcement, Fidelity highlighted how this new bundle would serve to reduce advisors' time spent on evaluating individual components of their tech stack by pre-packaging several of those core pieces together. But in practice, the move really seems like an effort by Fidelity to unbundle from its prior aspirations for Wealthscape, which is included in the new bundle as simply a "brokerage platform" – a far cry from the all-encompassing portfolio management solution it had once aimed to be (that in theory would have obviated ever needing a solution like Advyzon to plug in externally).

For advisors, Fidelity's new tech offering does provide more choice and flexibility (at least for those with the $100M+ in assets rumored to now be required to custody with Fidelity). Advisors who like Wealthscape's current breadth and capabilities can continue to use it, while advisors who prefer Advyzon (which was the highest-rated performance reporting solution in the 2023 Kitces AdvisorTech Technology) will have the ability to buy it at a 20% discount. With the additional benefit that an independent provider like Advyzon may be more attractive for independent RIAs that want to avoid becoming too reliant on their custodian for the technology they use, as well as those who use (or plan to use) more than one custodian, for which a third party solution is often more streamlined for working with multiple custodians at once (despite custodial technology offerings' frequent claims of having multi-custodial support).

Nonetheless, it's hard not to be stunned at the sheer level of investment that Fidelity has purportedly made into Wealthscape, that may amount to hundreds of millions of dollars or more, only to have its hand forced by advisor preferences into offering an option to use an independent technology solution like Advyzon instead. Or stated more simply: How many people at Fidelity may now be second-guessing the decision to build a competitor to independent portfolio management tools, only to have to capitulate and open the door wider to partner with those very tools instead (which it could have done without spending so much trying to compete with them in the first place)?

Which perhaps isn't all that surprising, given that most RIA custodians who have tried to build their own native technology solutions have struggled to keep pace, with only certain niche providers like TradePMR managing to sustain it over the long term. The spotty history of custodial technology offerings also raises questions about whether even the most tech-savvy custodians like Altruist will also struggle with the relative investment required to build out and then sustain a competitive advantage with their own technology, versus simply expanding integrations with independent technology companies who provide that capability as their sole function.

In the long run, it remains undeniable that with a business as lucrative as asset custody, there can be a healthy return on investment with anything that can make the assets more sticky, including investing into substantial internal technology builds. And notably, even Fidelity's most recent announcement also included a separate bundle that includes FMAX, Fidelity's own SMA platform, from which it can generate even more revenue via asset management fees – which means the allure for custodial platforms of offering technology isn't likely to fade anytime soon. However, the question will always remain about how effective custodians can be in building technology if the end goal in doing so is just to increase the stickiness of advisors and their assets, such that the tech itself remains outside their own core competency?

BlackRock Invests In GeoWealth… To Fuel Its Own Asset Management Distribution?

Asset management companies have a number of choices when it comes to distributing their asset management solutions to investors. On the one hand, they can work with institutions like pension plans and hedge funds, which have the benefit of providing large dollar allocations, but can also require a lot of resources to convince their internal portfolio managers, supporting investment consultants, and centralized investment committees, to invest in their products. On the other hand, they can instead work to get the dollars of retail investors, either by marketing themselves directly to DIY investors (a la Vanguard and T. Rowe Price), or by working with various "intermediary" channels, including distributing their funds through the financial advisors who sell or recommend them.

Within this intermediary channel there are of course numerous subsegments of different financial advisors. Asset managers can work with advisors on broker-dealer platforms or advisors who are employees of the broker-dealers themselves (or their RIA arms), or they can go out to the independent RIA channel one firm at a time. And notably, relative to most channels, independent RIAs have proven particularly challenging as a distribution path for most asset managers, since many independent RIAs tend to favor, well, independence – i.e., they're more stringent about maintaining the freedom to choose whatever investment products they please – as opposed to advisors whose product options are largely dictated by the home office.

Additionally, in an industry where many advisors are aggregated in some form (e.g., on broker-dealer platforms or under a corporate RIA umbrella), independent RIAs are harder to aggregate together to market to efficiently. Which has historically led to asset managers cutting deals with RIA custodians (for instance, via their product shelves or model marketplaces) as a way to distribute to many advisors at once. More recently, however, asset managers have expanded into making partnerships with technology providers that increasingly play a role in advisors' asset management decisions, including portfolio management platforms like Orion and Envestnet (and their associated model portfolio marketplaces), as well as "platform TAMPs" that provide technology, services, and support for advisors while providing a market of asset management options for advisors using the platform to choose from.

Which is why it's notable that GeoWealth, one of the fastest growing technology-driven TAMPs in the AdvisorTech landscape, has recently announced an $18 million investment from the mega-asset manager BlackRock – which likely-not-coincidentally comes just one month after the two firms announced a partnership in which advisors would be able to offer customized strategies like direct indexing, fixed income SMAs, and alternative investments in their portfolio models through GeoWealth's platform.

What's interesting about the deal is that GeoWealth reportedly has stated they weren’t necessarily looking to raise fresh capital – but neither was it lacking in ideas for what it could do with the influx in new cash, which it purportedly plans to use at least in part on developing Unified Managed Accounts (UMAs) that allow it to combine multiple asset types or investment strategies within a single account. Which will expand advisors' ability to deploy more varied portfolio models on GeoWealth, including (again likely-not-coincidentally) the kinds of customized strategies that BlackRock will be offering on the platform. In other words, BlackRock's investment in GeoWealth is really a direct investment in enhancing the capabilities of GeoWealth to support the distribution of its own products.

On the surface, an $18 million investment is essentially pocket change for BlackRock, which manages around $10 trillion in assets and has invested significantly larger sums into bigger distribution intermediaries like Envestnet. Still, the GeoWealth deal is an example of an asset manager becoming more vertically integrated in the distribution of its funds, i.e., owning or growing its influence within the marketplaces through which its own products are sold (similar to when movie studios also own the theaters where their films are shown, which was illegal for over 70 years before the court case banning the practice was overturned in 2020).

Fortunately, although there have been some questions about whether BlackRock's investment into TAMPs and other distribution channels could compromise those channels to favor BlackRock's products over other asset managers' in some way – in the form of anything from more prominent placement for BlackRock's strategies on the model 'menu' to (at the extreme) outright exclusivity for BlackRock on the platform – it appears at least for now that BlackRock doesn't plan to interfere beyond investing in the UMA structure that will expand GeoWealth's ability to offer more UMA-integrated strategies (which 'happens' to better enable advisors to choose Blackrock solutions, should they choose to do so). Because at the end of the day, as long as BlackRock's products receive some share of GeoWealth’s expanding market share, any growth of GeoWealth as a platform will incrementally accrue to BlackRock as well, and so investing in GeoWealth's growth effectively serves to fuel BlackRock's own growth, even without turning the TAMP into a proprietary platform for just BlackRock's products.

In the long run, though, some question does remain about what asset managers like BlackRock will ultimately do with the stakes they've taken in intermediary providers that support financial advisors, and when "passive" investment in a distribution platform might tip into more anticompetitive behavior. Yet at the same time, the ironic reality is that there's so much money in the "money" business of asset management, that some asset managers might really just be happy to see advisors (and the technology that they use) grow for the benefit of everyone – including themselves – which in turn has proven to be an ongoing source of capital to invest into the AdvisorTech ecosystem that arguably really is lifting up the state of advisor technology for all?

Vanilla Raises (Another) $20M As It Pivots From Estate Planning Software To Estate Document Preparation

The 2023 Kitces AdvisorTech Study found that the typical advisor spends between 4% and 6% of their revenue on technology, which covers everything from their CRM systems, portfolio management and performance reporting tools, financial planning software, and any other technology the firm needs for ancillary functions (compliance, document management, marketing, etc.). And in the vast majority of cases, that technology is priced as a flat, ongoing monthly software fee (though exceptions do exist, such as portfolio management tools that charge basis points and lead generation tools that charge a percentage of revenue).

But the end result for most advisor technology is that there's only so much market opportunity in total for any piece of software. When mature advisory firms average in the neighborhood of $500,000 to $700,000 in annual revenue per advisor, the all-in technology spend therefore usually comes in between $20,000 and $40,000 per advisor. Beyond that, any new software tool needs to competitively bid to either replace some other tool in the advisors' tech stack, consolidate multiple tools together, or free up advisor or staff time to produce net savings after the cost of the software – otherwise buying more technology would simply be a drag on the firm's profitability.

What's notable about the pricing of software is that it's fundamentally different from the pricing of services (including the advisor's own services), where pricing is usually offered per unit of service offered (e.g., per billable hour, per tax form filed, per dollar of assets managed, etc.), such that while technology companies can scale up simply by selling more units of the software, service firms can only grow by adding more staff to do the service work, and therefore price at the level required to maintain that staff. Which is why services are generally priced higher than software: Because of the higher staffing requirements to deliver the service, as well clients' willingness to pay a higher price to have someone else do the work for them.

In more recent years, the dichotomy between software and service business models has become more apparent across the AdvisorTech ecosystem, most prominently in the growing instances of technology providers expanding to become service providers (and pricing themselves accordingly). Which includes everything from portfolio management tools like GeoWealth that have grown into TAMPs with outsourced investment management services, to marketing platforms like Snappy Kraken that have added "done-for-you" outsourced marketing services, to the more recent rise of estate planning solutions like Vanilla, Wealth.com, and EncorEstate, that not only offer estate analysis software but also handle the preparation of many estate planning documents. Which in the case of estate document preparation increases the provider's revenue potential from the few thousand dollars (at best) per advisor that it would earn in pure software fees to a few hundred dollars or more for each of the advisor's clients who get their estate documents through the service. So for example, while a software provider might earn $2,500 per advisor for a software-only license, it would earn $25,000 from that same relationship if 50 of the advisor's clients got their estate documents prepared for $500 each (though in this case it's usually the client and not the advisor paying for the service).

In this vein, it's notable that this month Vanilla announced a recent capital raise that follows the launch in late 2023 of its Document Builder tool that allows clients to get trusts, wills and related documents done through the Vanilla platform. Although the size of the investment wasn't made public, the company has stated that it's raised over $66 million to date – which given their previous estimated funding total of $46.4 million, implies that this round added around $20 million in new capital.

Vanilla's recent pivot from pure estate planning software to estate document preparation service provider broadens the capabilities of what Vanilla provides to advisors on their platform – particularly in the domain of working with more affluent and complex clients, where Vanilla's estate planning and analysis software has most differentiated itself. As advisors aim to develop their relationships with high-net-worth clients both by going deeper into sophisticated planning strategies and by providing more 'white glove' services in-house, the combination of estate analysis and document prep is appealing as a way for advisors to accomplish both aims with one tool.

But at the industry level, the shift into document preparation places Vanilla more squarely in competition with others in the space that have already been offering some combination of estate analysis and document preparation, including the aforementioned Wealth.com and EncorEstate as well as (from more of a pure document preparation standpoint) Trust & Will. All of which are competing for the opportunity to generate hundreds of dollars per client, and/or thousands of dollars per advisor, by not just fulfilling a software need but by solving the challenge of getting clients set up with estate documents in a world where the cost of getting them from an attorney has been seen as increasingly unreasonable even for more affluent clients. And to that end, Vanilla is well positioned compared to the competitive landscape with its focus on supporting high-net-worth clientele, where its founder Steve Lockshin has very deep roots and experience in his own advisory business (whereas most of its competitors have focused more on the other end of the wealth spectrum, serving more 'mass affluent' clientele who just need some documents in place for asset distribution and guardianship purposes).

In the long run, the question is just how big the market for estate planning document services really is among advisors. Unlike, for instance, tax returns, clients don't need to come back and re-prepare their estate documents each year, and at best they might look to revisit their documents every 5-10 years (or even less frequently if the documents are drafted with some degree of flexibility). Which means that realistically, an advisor who has 100 clients at full capacity may only actually need 5 to 10 sets of documents per year – which ironically may only add up to around what the provider would have earned from a software-only fee in the first place. And the while there does seem to be potential for advisors to leverage document preparation to help their clients get the estate documents they need while expanding and deepening their client services (since finding estate documents for clients is a real pain point for advisors in the aggregate, even if it doesn't come up frequently for each individual client), time will tell whether Vanilla's success in raising capital reflects the actual market potential for their services, or if it will prove to be overexuberant about the latent demand for estate planning documents made easier and more cost effective through technology.

Hearsay Sold To Yext For $125M, Closing The Hype Chapter Of Advisor Social Media Marketing

In the 2000s, one breakthrough social media platform after another emerged in relatively quick succession: Within 5 years of each other, LinkedIn, Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter all launched and gained rapid traction. All of a sudden, consumers were spending inordinate amounts of time on these platforms, especially after the rise of smartphones put everyone within arm's reach of their social feed – which led to speculation at the time that social platforms could displace email or even websites themselves.

In the context of the financial services industry in particular, social media was hailed as the future of marketing for financial advisors. The idea was that the ability for any advisor to post or share out useful information would make it exponentially easier to get in front of prospective clients, which in turn could spell the end of traditional marketing campaigns and even obliterate the need for cold calling or cold knocking as a way to get established.

The caveat, however, is that from a regulatory perspective, social media was (and still is) considered a form of advertising and marketing communications, which means that any social media posts are subject to compliance review and approval. Which quickly became problematic for advisory firms when advisors' requests for compliance approval went from 1–2 pieces of marketing collateral per year to 1–2 social media posts (or more) per day – utterly drowning compliance departments in review and approval tasks, and leading firms (especially the bigger ones) to ban advisors from using social media altogether, since they had no scalable way to approve and monitor it.

But as often happens, when technology creates problems, new technology arose to solve them. In this case, Hearsay, along with other providers, aimed to help firms manage the sheer volume of compliance review necessary for social media marketing at scale, providing systems that made it easier for advisors to generate social media content; for compliance to review, approve and monitor advisors' social media activity; and for firms to scale their content distribution by making centralized investment and financial posts that could be shared out on all of their advisors' profiles.

With solutions like Hearsay effectively unlocking social media for financial services firms, the prevailing view was that social media was the future of advisor marketing (as it was also seen as the future of marketing in almost every other industry) – which led to a number of leading players in the space to raise eye-popping levels of capital as they built to fulfill those aspirations. Most notably, Hearsay raised a total of $51 million in 3 rounds led by Sequoia Capital spanning less than 3 years – an enormous amount at the time in the early 2010s, when few AdvisorTech providers had received any investment from venture capital firms. At its 2013 peak, Hearsay was valued at an estimated $171 million.

Fast forward to just over a decade later, however, and although social media certainly remains ever present in our lives (remarkably still anchored around the original giants of Facebook, Twitter/X, LinkedIn, and YouTube, though other platforms like Instagram and TikTok have also gained prominence), it hasn't turned out to be anything like the dominant advisor marketing channel it once seemed destined to be. Ironically, this was driven in no small part by social media's own popularity: Once everybody was on social media, it became harder to stand out from anyone else, let alone for consumers to figure out who was actually trustworthy (a problem that has gotten even worse in recent years with the rise of 'finfluencers' who come from outside the advisory world, and face few consequences for sharing misleading information). Furthermore, it eventually became clear that advisors who did become successful through social media became so by the uniqueness of what they had to say – exactly the opposite of the cookie-cutter approach that made social media marketing scalable for most firms, and that technology like Hearsay was best equipped to enable.

And so it's notable, though not entirely surprising, that Hearsay recently announced that it was selling itself to the digital branding platform Yext for $125 million (plus a contingency consideration of up to $95 million, though that appears to be based on how successfully Yext can leverage the solution for its existing customers).

For advisors who use Hearsay, the deal doesn't necessarily change much. Hearsay still generates a reported $60 million of revenue, and Yext (which is a public company) isn't likely to want to disrupt that revenue stream. So the large range of financial services firms where Hearsay is embedded (which includes BlackRock, Schwab, and New York Life), and the reported 260,000 advisors and insurance agents who use the service, can realistically expect to continue using Hearsay (while probably also being pitched on Yext's other products and services).

The real impact of the Hearsay deal is at an industry level, where Hearsay's exit at a lower valuation than where they raised capital 11 years ago (or, if they manage to hit their contingency targets and achieve the full potential sales price, at a rate of return that doesn't even outpace inflation over that time) shows how being anointed the "next big thing" in AdvisorTech doesn't always justify a huge valuation. Because in reality, the advisory industry is only so big, and so even Hearsay's relative success in achieving market penetration and revenue (and Hearsay's 260,000 users and $60 million in revenue are certainly far higher than most AdvisorTech companies) still fell short of expectations for a company that raised $51 million in its first 4 years of existence. Or stated more simply, as with any investment, it's not just about how big you expect the company to get: The price you pay to invest matters too, and if everyone else expects the same exponential growth and values the company accordingly, it gets harder and harder (and sometimes effectively impossible) for it to live up to those expectations.

To that end, it's still notable that Hearsay really did build a big and successful AdvisorTech company by capturing the industry's pivot into social media just as it began to emerge, and notwithstanding the results for those who invested at its peak, it does go to show the size of the opportunities available when building technology for advisors. At the same time, it's a reminder that AdvisorTech, like any startup field, can raise 'too much' money relative to the actual market opportunity, especially when excitement over the possibilities for new technology crosses over into overexuberance (which seems particularly notable at a time when AI is often being touted as the future of advisor technology). Ultimately, there are still opportunities to build great companies, however, in a market where success can be measured in being valued in the tens of millions of dollars rather than being the next billion-dollar unicorn.

Wealthtender Partners With Hadrius To Scan Client Testimonials For Compliance With SEC's Marketing Rule

Advisory firms have the obligation to implement policies and procedures meant to identify and prevent wrongdoing, both in the delivery of advice to clients and in the marketing and promotion of their services. In fact, the entire origin of the fiduciary obligation for RIAs stems from the SEC's anti-fraud provisions requiring advisors to be truthful and accurate in how they describe their services and represent themselves to the public. This scrutiny around the way firms market themselves included a decades-long ban on firms using any kind of client testimonials in their advertising, due to concern by regulators that firms might cherry-pick the experiences of only the clients that had the best performance results, painting a too-rosy picture that wasn't representative of the typical client experience. And even though the SEC ended its ban on testimonials in 2022, advisors still have a duty not to be misleading in the testimonials they display to the public, and those testimonials (like all of their other advertising and marketing communications) must be reviewed for compliance purposes to confirm that they aren't misleading about the firm's services, investment performance, or other results.

From an advisory firm perspective, managing these compliance obligations becomes challenging as a firm grows and adds advisors, since each advisor produces additional marketing material that must be reviewed and approved. And the compliance burden per advisor has only grown over the past 20 years as client and prospect communication has increasingly moved away from in person meetings and phone conversations to email and other digital means, creating even more pressure on firms to review an exponentially growing volume of marketing and related communication.

In the last couple of years, however, the rise of ChatGPT and other Large Language Model-based tools has led to a proliferation of technology that can quickly scan through large bodies of text and pull out what it recognizes to be key information. And while much of the industry is still debating where these AI tools can actually be used effectively in a way that saves time for advisors, compliance reviews represent arguably one of the strongest use cases for AI in advisory firms, given that parsing large volumes of text for particular information is exactly the challenge that takes up so much time for compliance departments. And at least conceivably, an AI tool trained on specific compliance rules and regulations could do a better job than the current most common approach of searching communications for individual keywords like "guarantee" (which can miss potentially questionable material if it doesn't happen to contain the exact keyword being searched for), since an LLM would be much better equipped to recognize the actual meaning of the text, or at least do so well enough to flag it in order for a human to provide a full review.

In this context, it's notable that Wealthtender, a platform supporting advisors in gathering reviews and testimonials from clients, has announced a partnership with Hadrius, an AI-powered compliance review tool, to launch what they're calling a Testimonial Compliance Scanner. The new service will instantly scan any of an advisor's testimonials that come through the Wealthtender platform to confirm that they're compliant with the SEC's Marketing Rule, and flag any potential violations for manual review.

For advisors, one of the core anxieties around client testimonials is that clients don't necessarily know what is or isn't allowed by the SEC – and yet, if the client leaves an inappropriate testimonial that the advisor inadvertently misses, it's the advisor who would risk getting in trouble with the SEC. And so one of the virtues of a testimonial platform integrating a tool like Hadrius is that it can automatically scan every word of every testimonial. Which on the one hand does require the advisor to actually trust that the technology can work as advertised and flag every potential violation (without also flagging so many false positives that the compliance department is swamped with reviews of testimonials that are actually fine) – but on the other hand, with the compliance tool being embedded directly into Wealthtender rather than requiring a third party piece of software, the advisor can always turn off the compliance scanner (without being out any additional software fees) if they don't feel like they're getting any value from it.

Which serves to highlight an emerging question around the use of AI tools by advisors in general: Whether it's better to have a standalone tool that applies AI to a particular function (e.g., AI-driven compliance, AI meeting notes, AI document scanning, etc.), or whether it's better to build AI natively into the place where the action actually happens, such as having a client testimonial platform that also uses AI to scan testimonials for compliance. Because while many advisors are certainly excited about AI and its possibilities for the advisory industry, the greater number aren't necessarily excited about AI per se (at least to the extent that they're motivated to buy a standalone AI tool) – they simply want software that does what they need it to do, and if it happens to use AI to work better, then so much the better.

All that being said, it remains to be seen if the new partnership with Hadrius will lead to more traction for Wealthtender in the competitive lead generation environment. Because in the end, a lack of an efficient compliance review process isn't the reason most advisors don't use testimonials in their marketing now, more than 3 years after the SEC reversed its stance on advisor testimonials. For many, it's the fear of what clients will actually say when asked to leave a review, uncertainty about how to ask for testimonials in a compliant way, and not having a marketing process built to productively leverage testimonials. And even for those who do use testimonials in their marketing, the relative infrequency at which new testimonials come in (which might at best be one per month) limits how much actual time savings they can realize from automating the compliance review portion.

Nevertheless, for the small but growing number that do use testimonials, the rules around compliance review do still exist – for which case Wealthtender's Testimonial Compliance Scanner seems like a key step forward to provide a necessary compliance function with less time investment for the advisor.

Morgan Stanley Debuts Internal "Debrief" AI Meeting Assistant

It's been nearly 2 years since OpenAI and its ChatGPT tool went mainstream, leading seemingly everybody to try it out to see what it was capable of. And at least while the novelty of it was still fresh, chatting and interacting with ChatGPT really did produce a "wow"-level experience, as no previous publicly available technology had been as capable of instantly synthesizing human-like responses and coherently structured writing in response to user-submitted questions.

But in the time since then, there have been no small number of questions about the data used by OpenAI to train the Large Language Model (LLM) that powers ChatGPT (with similar questions for Google, Microsoft, and other tech companies with their own LLM-based tools). Namely, who owns the information that was hoovered up by OpenAI and other providers? And what compensation are they owed for the revenue those tools generate for their creators?

From the perspective of financial services in particular, the questions get even thornier. If an AI tool is built to perform some financial planning function, it needs to be trained on financial planning data – which presumably comes from real-life clients. If a client's data is used to train a third-party LLM tool, then who provides it to the developer? And what happens to the data after it's used to train the model? If an advisor uses the AI tool, will their clients' data get pulled into the LLM as well? So while it may or may not truly constitute a privacy issue for the client, some firms may still be uneasy about the provenance of data used in third-party AI tools.

The obvious alternative would be for a firm to build its own in-house AI model, where the data would all be from its own internal clients and there would be no concern about what would happen to it in the hands of a third party. Except because of the massive amounts of data needed to actually train an AI model, it's only a realistic option for the very largest firms that actually have all that data to feed into the model. Firms like Morgan Stanley, with its base of around 16 million clients, and which announced in March of 2023 a partnership with OpenAI to build in-house tools with OpenAI technology built on Morgan Stanley's own reams of internal data and debuted its first product in the form of a research assistant tool that September.

And now Morgan Stanley has gone one step farther with its internal AI tools with its launch of Debrief, the wirehouse's version of an AI meeting notes tool that generates a summary of the conversation, creates a first draft of a follow-up email for the advisor to edit and send to the client, and saves the meeting notes into Salesforce for archiving purposes.

Of course, meeting notes and related post-meeting follow-up tools have already become popular use cases for AI in the rest of the advisory world, given the sheer amount of time advisors spend on meeting preparation and follow up (about an hour each per meeting, according to Kitces Research on the Financial Planning Process). And the free flowing nature of most client meetings is conducive to AI tools and their ability to process large amounts of verbal communication and summarize the key points and applicable takeaways. Morgan Stanley is one of only a handful of firms for which it was practicable to develop its own proprietary tool, based on its own internal data, since most medium and even large advisory firms simply don't have the amount of internal data available to train an LLM.

But while it remains impressive that Morgan Stanley can create its own in-house meeting notes tool, the question remains whether it will actually prove effective enough to be an improvement over emerging standalone solutions like Fathom, Jump, Zocks, and the many other tools flooding the marketplace today – which is a challenge faced by any large firm that attempts to build its own in-house technology that can keep up with external solutions, made even more difficult by the rapid pace of development and disruption in AI today. But in an environment where the industry and regulators haven't quite figured out where to draw the compliance lines on collecting and using information captured in meetings, Morgan Stanley largely forgoes those concerns by building their own LLM that 'just' uses the data of clients who are already at the firm, and keeps it all within the firm's walls rather than interfacing with a third-party vendor.

In the long run, the industry debate between building versus buying technology will remain, as large firms (who usually the only ones for whom "build" is even an option) decide what's worth making from scratch versus using what others have already developed. But in the context of broader questions about the impact of AI tools ingesting client meeting data, and the ensuing discussion around data privacy, what Morgan Stanley's Debrief highlights is that maybe AI-driven tools will be the point where scales tip in favor of building internally, simply as a way to protect internal data – at least until third-party providers get firms comfortable with sharing it externally.

In the meantime, we've rolled out a beta version of our new AdvisorTech Directory, along with making updates to the latest version of our Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map (produced in collaboration with Craig Iskowitz of Ezra Group)!

So what do you think? Is it better to use third-party technology than a custodian's "all-in-one" solution, even if the custodian's is less expensive? Is BlackRock's investment in GeoWealth simply an investment in the TAMP's future growth, or will there be too strong of a temptation to push its own products on the platform? Does it make sense to use software like Vanilla to prepare clients' estate planning documents when they only need to be updated once per decade? Let us know your thoughts by sharing them in the comments below!

Leave a Reply