Executive Summary

The traditional role of a financial advisor is to provide financial planning services to their clients, or at least to support the financial planning process in an advisory firm. However, with the growing number of programs that provide the educational foundation required by the CFP Board for rising certificants to earn their CFP designations, there is an increasing demand for qualified teachers of financial planning. This growing opportunity has appealed to many advisors – not only has it offered new career options for financial planning professionals as an alternative to client-facing work, it can also be a unique marketing opportunity that increases the credibility of an advisor as a well-qualified financial planning expert in their work with clients, and gives firms an opportunity to see first-hand the top students in a local program that might be future hires (at least within the limits of what university conflicts-of-interest policies will allow for their instructors).

However, there are many different types of teaching roles that a financial advisor can consider. A position as a part-time instructor may make the most sense for advisors who want to continue serving financial planning clients. Compensation typically ranges from $3,000 to $7,000 per semester course, though part-time instructors at the undergraduate level are generally required to have earned a Master’s degree in a related field in order to get the paid teaching opportunity. For those who are interested, aside from the time commitment of actually teaching courses (which typically involves approximately 45 hours per semester per course), advisors should be aware of the time commitment involved in preparing for the course (for the first-time instructor, this can involve several hours per lecture given). Accordingly, given the relatively low salary range and high time commitment, financial advisors who choose to teach in these roles generally do so out of a love for teaching and as a way to give back to the industry by helping to prepare new advisors.

Full-Time instructors, on the other hand, tend to have a regular assignment of courses with some certainty of when and which subjects will be offered throughout the year. The job security of a full-time instructor is much more stable than that of a part-time instructor and, for non-tenure track positions (i.e., less permanent appointments with little or no research commitments), annual compensation levels generally start in the $50,000 to $80,000 range. However, full-time positions will make it more difficult for an advisor to continue working outside the classroom (though it may still be possible); thus, advisors will typically need to be willing to give up work in their financial planning practices, and should be prepared for an academic career (and academic compensation levels). In addition, advisors again will generally be required to have earned a Master’s degree and have some relevant professional experience for a full-time instructor role.

Individuals interested in pursuing tenure-track professor roles will find opportunities at research and/or teaching universities with financial planning PhD programs (and occasionally PhD programs in other fields, such as Family and Consumer Sciences), though the requirements to qualify for an appointment are much more stringent than for other types of teaching roles. New “assistant professors” can expect starting salaries to range widely from $60,000 to $130,000. While maintaining a financial planning practice may be very difficult for a tenure-track professor because of the work involved in both teaching and research, advisors can find ways to stay connected to their firm, potentially through occasional ad hoc planning work, relying on other firm partners, or by outsourcing work to others.

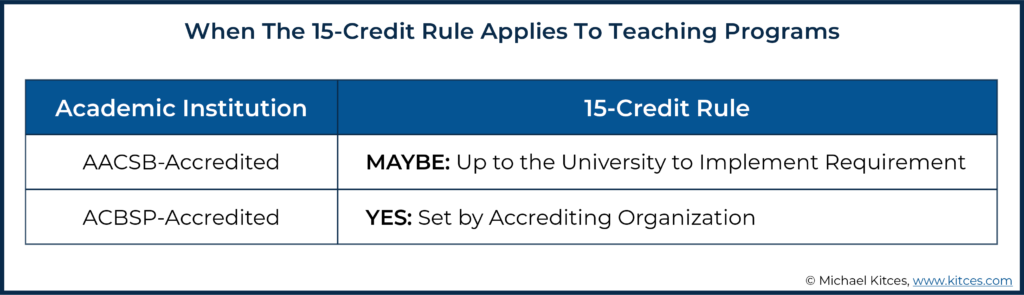

For those in a tenure-track position, earning tenure involves a long process unto itself, but their positions become very secure as tenured faculty positions are permanent, lifetime appointments (where it’s very difficult to get fired short of very substantive failures to do the core job). However, research universities will generally require a significant amount of research to be done by their faculty in a tenured professor role. For example, some popular CFP Board Registered PhD programs expect their faculty to publish an annual average of three articles in peer-reviewed academic journals every year, though the actual expectation varies greatly and can be gauged by determining what tenured professors published during their own probationary (tenure-track) period. In addition to research requirements, some institutions (e.g., those that are accredited by the Accreditation Council for Business Schools and Programs, or ACBSP) require individuals to have 15 finance graduate credits in order to teach in their programs, though other institutions (accredited by the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Businesses, or AACSB) don’t necessarily share this 15-credit requirement, but may have their own standards (which vary by institution, and could still include a 15-credit requirement) that define requirements for teaching eligibility.

Ultimately, the key point is that there are many financial planning teaching opportunities, some of which have relatively low education and experience requirements that can be managed by a financial advisor without having to give up their practice of financial planning itself. On the other hand, for those who actually wish to pursue a financial-planning-based career in academia on a full-time basis, there are also growing opportunities for full-time instructors and even tenure-track faculty positions at a research university. Regardless of the role, though, teaching opportunities in the financial planning field can serve as a great way for advisors to enhance their current job roles (or even switch careers altogether!) and to contribute to the profession by supporting the education of aspiring financial planners!

With the rapid rise of CFP educational programs, there is an increasing number of opportunities available to individuals who want to help teach the next generations of CFP professionals. However, navigating academia (either on a full-time or a part-time basis) can be a confusing endeavor with many considerations facing individuals interested in teaching in a CFP program, regardless of whether they want to pick up some extra teaching on the side or pursue an academic career on a full-time basis.

There are many different paths an individual may want to pursue while teaching in a CFP program, so it is important to first understand one’s goals and objectives for their teaching pursuits. In this article, we examine three common paths available to financial planning academics:

- Part-time work as an instructor

- Full-time work as an instructor

- Tenured/Tenure-track professor at a teaching or research university

Each of the paths above can have vastly different requirements, responsibilities, and earning potential, so it is important to understand how academic positions vary more generally.

However, there are also some similarities and considerations that apply across most academic positions, so we will cover those first.

Will A University Affiliation Help A Financial Advisor’s Business?

Many financial advisors who are considering a teaching position may wonder whether a university affiliation might help them bring in more business. For instance, being affiliated with a university may improve a prospective client’s perception of a financial advisor (e.g., there may be a halo effect where the prospective client might assume that the advisor’s university role reflects positively on their ability to deliver financial advice). Yet while there may be some grounds for such an assumption, advisors hoping that teaching will be a significant driver of new business may be disappointed.

First and foremost, the university an advisor works for will likely have restrictions related to the use of the university’s name in any marketing efforts (particularly public universities). Generally, it is okay to state factual information about your employment (and advisors are required to disclose outside employment information via their ADV), but the use of a university’s name, or the teaching position itself, in a manner that implies any sort of endorsement from the university will almost certainly be prohibited.

Many universities publish conflict-of-interest and similar policies online, which can help provide a sense of the typical rules that may be enforced (e.g., see here for a list of policies at Iowa State University).

There are also considerations to ensure that faculty members do not misuse any university resources for business purposes. It should go without saying that using university letterhead, business cards, logos, etc. within an advisor’s own business will be against university policy.

However, there are more complicated considerations with respect to the incidental use of a university-issued laptop, email account, etc. Often, incidental use is allowed (and sometimes the use of resources, like office space, might be allowed if the university is paid a market rate for their use), but there are other good reasons to keep any advisory business activities entirely separate from those involving the university.

For instance, even incidental use of a university email address or computer presents confidentiality concerns, since the university owns and can access the computer and all email content. If working for a public university, all email correspondence will also be subject to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, so all email messages will effectively be open to public review (there are some exceptions or content that would be redacted, but most communication would be available to the public). Which means any client correspondence from a university email address or computer may no longer be private (and likely against the advisor’s own Client Privacy Policy).

Advisors must also be careful with respect to hiring interns or having any other employment-related relationship with CFP students, at least while the advisor is their current professor. The primary concern with hiring students is the significant potential for abuse of power by an instructor with employment-related student relationships.

It is generally a best practice to wait until after a student has graduated before entering into any sort of employment arrangement with a now-former student. Even if a student has completed a faculty member’s course, there may be concerns that a faculty member could still abuse their power while a student is in a program (e.g., threatening to terminate employment if a student doesn’t assist with a research project, withholding an affirmative vote on a thesis/dissertation for employment-related reasons, etc.).

That being said, there may be cases where precautions could be taken to allow for a student to participate in an internship with a firm an instructor is affiliated with, so it is not something that can never be done, but any such arrangements should always be made with full communication between and in consultation with relevant authorities within a university (e.g., department chair, dean, etc.).

So, in short, while there will likely be some halo effect associated with a university affiliation as a form of credibility, and possibly some secondary benefits such as advantages in recruiting future employees, there are also a lot of complications and university rules around business activities outside a faculty appointment. Accordingly, it is easiest for advisors to maintain complete separation between their work as a financial advisor and an instructor to avoid the complications that may arise from potential conflicts of interest or from hiring students for positions at the advisor’s firm (or at a minimum, it is crucial to report any potential conflicts of interest and to receive university guidance and approval for how to deal with those conflicts).

Which means in the end, financial advisors seeking university affiliations primarily for business purposes will likely find themselves disappointed. At best, the credibility of being affiliated with a university CFP program, and having a pipeline to prospective students as future employees, will likely be a useful but ancillary benefit.

Part-Time Work as a CFP Program Instructor

Ostensibly, the most likely track for financial advisors to teach in a CFP program is to pick up part-time work as an instructor. Such work could be done on an ongoing basis (e.g., a part-time instructor who regularly teaches a course over several academic terms) or simply on a one-time basis (e.g., contracted to teach a course with no guarantee to teach in the future), and is often characterized as an “adjunct professor” or simply “instructor”.

This path can make a lot of sense for advisors who want to be involved in teaching to give back to the profession or nurture the next generation (or for some of the ancillary benefits of ‘professor’ credibility and a pipeline of future employees), but primarily still want to run their advisory practice. Given how lucrative financial advising can be as a career, compensation for teaching a course will most likely not be a strong motivator for advisors.

As while there may be exceptions, in most cases, compensation for teaching a single semester-long course typically falls in the $3,000 to $7,000 range. And once the advisor factors in the time required to prepare lectures and manage administrative duties (e.g., grading and attendance) beyond the 45 hours of actual time in class over a typical semester, the hourly pay will likely only be attractive to advisors who want to teach for the love of doing so (or who are early in their career and may really need some additional income).

The requirements to become a part-time instructor are the lowest in comparison to the requirements for full-time and tenure-track teaching roles. Generally speaking, to teach as a part-time instructor at the undergraduate level, you will likely need to have a Master’s degree.

Different schools may vary in how selective they are regarding the field of your Master’s degree (e.g., a financial-planning-related Master’s degree, or any graduate degree?), but instructors will generally have more leeway in their degrees than individuals might in other areas.

If you have an MBA or a Master’s in a relevant field (e.g., finance, accounting, financial planning, psychology), that is probably sufficient for teaching, and particularly if you also have your CFP marks. Furthermore, industry experience is often valued in instructor or adjunct professor roles, and professional experience may be equally, if not more, important than your academic experience in some cases.

If there is a local college or university you are interested in teaching in, a good first step would be to reach out to that program director. Depending on the exact position being sought, schools may need to go through a formal search, but often universities are happy to have qualified individuals willing to teach, so they may also maintain a less formal list of individuals who are willing to teach.

Through this process, you may also learn that a program may not have much need for instructors, but a conversation with the program director is a good place to start.

The most meaningful barriers to teaching as a part-time instructor are probably more so related to uncertainty regarding how to teach a CFP course in the first place. That is a big topic on its own, but there are a few things to remember in this situation: (1) almost everyone feels uncertainty about their teaching approach and teaching methods when teaching at first, (2) almost everyone feels like they are being thrown into the fire during their first courses, and (3) there are probably many individuals at a college or university who would be happy to provide some mentoring.

So, advisors who really want to teach shouldn’t let the intimidation of doing so stop them. The Columbia University Financial Planning Teaching Seminar is one excellent resource that can help advisors learn how to teach, and will provide connections to other individuals who may be going through the same process.

Notably, unlike other types of teaching pathways (e.g., tenure-track professors), instructors are not expected to publish research as part of their adjunct professor role. Publishing research in financial planning journals (e.g., Journal of Financial Planning, Financial Services Review, Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, Financial Planning Review, Journal of Financial Services Professionals, Journal of Personal Finance) could be something to consider for the purposes of contributing to the body of knowledge of the profession, and having some personal research work to talk about in class, but it won’t be a requirement to receive or maintain an instructor position.

Good part-time instructors can be very valuable to a CFP program. It is probably no surprise that many professors lack insight into real-world, day-to-day operations of a financial planning practice, so this perspective can be very valuable to students, and professionals can be a resource for helping students get connected to their local industry.

Ultimately, teaching on a part-time basis is more of a way to “give back” to the industry and help prepare the next generation of financial planners. While perhaps gaining a little credibility for affiliation with the university, and some dollars for your time (albeit still nowhere near the Return On Time of being a financial advisor working with clients directly).

Full-Time Work as a CFP Program Instructor

Working as a full-time instructor has the benefit of generally providing a bit more stability in teaching load, courses, etc., from semester to semester. As while part-time instructors are often subject to the uncertainty of when/whether a course will even be taught from one semester to the next, full-time instructors typically have an expected ongoing cycle of classes they (can expect to) teach. However, individuals in these positions will still lack the type of job security that tenured professors have, and the compensation is likely going to start out in the $50k to $80k range (substantively less than what full-time tenure-track professors at a comparable university would make), albeit with higher salaries available within business schools (which tend to have higher compensation across the board than CFP programs housed within other types of academic programs).

Titles for full-time teaching jobs may vary. For instance, while many in these roles may be called “instructors” (or “lecturers” or “adjunct professors”) similar to part-time roles, there are also non-tenure-track full-time teaching positions such as a “clinical professor” or “professor of practice” that would be similar in many respects (e.g., a non-tenure-track position with the primary emphasis on teaching) except for higher expectations regarding one’s professional experience.

Many full-time instructors will teach the number of courses that are considered a full-time teaching load at their college or university. In general, four courses per semester is considered a full-time teaching load, but sometimes lower-ranking colleges and community colleges may require higher teaching loads of full-time instructors (while professors with research responsibilities might only teach two courses per semester).

One thing advisors can consider when evaluating teaching opportunities is that teaching loads can and do vary quite a bit based on how many different courses (often referred to as “preps”) instructors are required to teach. For instance, two instructors each on a 4/4 load (i.e., teach four courses each in the fall and spring semesters) would need to put significantly different amounts of time into their teaching if one instructor is teaching four sections of the same course (four courses but only one prep) and the other is teaching four different courses (four courses that entail four preps).

Furthermore, classes are generally easier to teach once you have prepped them once in the past, so teaching the same courses semester-to-semester is going to be less burdensome than being expected to develop (and/or needing to prep) new/different courses.

Working as a full-time instructor is likely not feasible for most financial planners, since it truly will be a full-time job. It is still possible to maintain a financial planning practice on the side as a full-time instructor in a CFP program, but full-time instructors will be much more limited in the amount of time that they can devote to growing their practice in comparison to an instructor who is just teaching an occasional course.

That said, depending on the appointment (i.e., whether the work is based on a year-round 12-month contract or a 9-month contract that includes a summer break), you may still have a significant chunk of time (summer and winter breaks) to focus on your practice (and may work well as part of a “meeting surge” strategy).

Similar to part-time instructors, full-time instructors will also have less rigid academic qualifications (at least relative to tenure-track professor roles). A Master’s degree and relevant professional experience will likely be sufficient, although it would probably be harder for someone with a lot of professional experience but no Master’s degree to secure a full-time instructor position than it would be to secure a part-time instructor position.

Like part-time instructors, full-time instructors generally do not have any research responsibilities. However, particularly if you find yourself in an instructor role but would like to move into a tenure-track professor role at some point (probably more likely among those who are interested in full-time instructor positions versus part-time in the first place), then you will need to maintain an active research agenda (even though it is not a requirement of your current position).

The reason for maintaining an active research agenda is that doing so will likely be necessary in order to get a tenure-track (TT) position in the first place. In many respects, it is not ‘fair’ that hiring committees for TT positions aren’t going to be adjusting for one’s teaching load when comparing candidates, but, all else being equal, a candidate with five publications is going to look more attractive on paper than a candidate with one publication, and many TT positions are going to focus primarily on research first when evaluating candidates (though that’s not to say that other factors aren’t important – they are – but candidates without an active research agenda likely aren’t going to make the first cut).

More generally, though, the point is simply that while full-time instructor positions are primarily student-facing “teaching” positions, tenure-track (and actual tenured) professor positions are often research-centric positions (or at least have substantive research publishing expectations). Which means financial advisors who prefer to focus on teaching will likely remain at the full-time instructor level, while those who want to pursue tenure-track professorships will need to be prepared for and likely want to start bolstering their research skills and accomplishments.

The Academic Tenure-Track Process

Before we cover work within tenure-track CFP programs, it can be helpful to cover some basic considerations for securing a tenure-track position, which provides an opportunity for ultimately earning tenure.

Earning tenure is important because tenured faculty positions are permanent, lifetime appointments from which a professor can be terminated only for a limited number of reasons (e.g., incompetence, elimination of the position due to financial constraints of the university, etc.). Tenure was established in the interest of encouraging intellectual discourse by offering academics the freedom and autonomy to explore and research topics in their fields of expertise (without the risk that university politics could result in their termination for potentially controversial research).

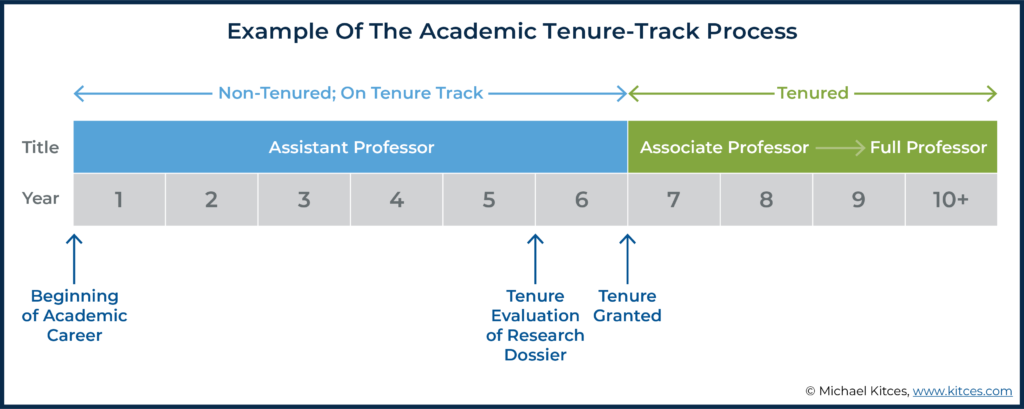

Most schools with tenure-track positions will use a six-year tenure clock. Generally, professors begin their academic careers as an “Assistant Professor” (non-tenured but on the tenure track) and will be evaluated for tenure in their sixth year. Which means that they generally only have five years to actually get research published since they will need to submit a tenure dossier for evaluation about a year before their clock expires (as the tenure evaluation process itself includes a lengthy internal and external review of the dossier).

If professors are successful and earn tenure, the granting of tenure will often occur simultaneously with a promotion to an “Associate Professor” position. If a professor doesn’t earn tenure, then they will generally need to look for new employment. At this point, some may choose to leave academia altogether, while others may seek positions with other universities where they can begin the tenure-track process anew.

The final promotion rank of many tenured professors is to be appointed at the level of a “Professor” (i.e., no associate or assistant prefix) or what might be referred to as a “Full Professor”. Unlike the six-year tenure clock, there is less standardization regarding the progression from associate professor to full professor once becoming tenured, but often it will still take at least another five years of work to receive this promotion, and individuals who do receive this promotion need to demonstrate sustained progress in their research and teaching beyond what they accomplished when receiving tenure. There is also no guarantee an individual will receive this promotion, and many professors are never promoted beyond the associate level.

If an individual still wants to pursue earning tenure after being denied tenure at another university, they will likely have to do so at a lower-ranking university (based on relative prestige within a field, which often aligns with the prestige of a university generally, but could deviate within a specific field) or possibly within a program that provides a better fit for their specialty. But those who are open to pursuing instructional or other non-tenure-track positions that don’t require the same degree of research expectations will have more options.

There are a lot of misconceptions about tenure (e.g., that professors with tenure are impossible to fire), but once a professor has tenure, it is true that they are much harder to fire, and it is a pretty desirable job to have. For this reason, there’s a lot of competition for such positions, and the primary way professors compete for these positions is via their research. So, where should researchers publish?

Unfortunately, the answer to this question is, “It depends”, but there are some general considerations with respect to different types of CFP programs one might have a tenure-track position in.

Tenure-Track Professor at a Teaching or Research University

If you actually want to pursue an academic career on a full-time basis, often tenure-track (or tenured) positions are the most highly sought-after positions.

Notably, though, a tenured professorship is different in practice depending on whether it is at a ‘teaching’ university, as distinguished from a ‘research’ university, where the primary difference in positions between these two types of universities is the balance of teaching and research responsibilities.

A teaching load is often expressed in terms of how many 3-credit courses a faculty member teaches each semester. So, a 3/3 would indicate that a professor is required to teach six courses in a year, generally compromised of teaching three in the fall and three in the spring.

At teaching universities, teaching loads will range from a 4/4 to a 3/3, although even higher teaching loads are not unheard of. Once you get down to a 3/2 teaching load, though, some of these universities may at least aspire to be more research-oriented (e.g., a growing public university that wants to move towards being a research university).

By contrast, at research universities (e.g., “R1 universities” as ranked by the Carnegie rankings), you generally will not see teaching loads higher than 2/2, and sometimes teaching loads may be lower (and this does vary by field; a 2/2 may be considered a high teaching load at a research university in some fields, but 2/2 is pretty standard at financial planning programs).

Interestingly, although one might expect that the focus for tenure evaluation in a teaching university would be teaching, the focus actually tends to still be more so on research. Of course, these faculty are held to very different standards than those at research universities, but publishing is still crucial for tenure in almost any institution.

Furthermore, if you want to advance your career as an academic (in the sense of moving up in institutional prestige without jumping off of the tenure track), then research is the primary way that you do so. Landing a huge grant can open up doors as well, but that’s easier said than done, and there’s probably more of a stochastic (i.e., random and uncertain) element to that in comparison to the daily effort of continuing to advance one’s research agenda.

Some good resources for those who are interested in advancing an academic career include:

- Tenure Hacks: The 12 Secrets of Making Tenure by Russell James (Note: Russell James is a professor of financial planning at Texas Tech)

- Good Work If You Can Get It: How to Succeed in Academia by Jason Brennan

- The Professor Is In: The Essential Guide To Turning Your Ph.D. Into a Job by Karen Kelsky

Salaries are going to vary considerably based on the type of program one is interested in. For assistant professors just starting out, base salaries could probably range from $60k (e.g., CFP programs outside of business schools and core financial planning programs) to $130k or more (e.g., finance positions in AACSB-accredited business schools).

On top of base salaries, professors often also have opportunities for teaching in the summer or receiving a salary for grant-related work that might increase their pay up to an additional 33%, although these opportunities for additional compensation are generally not guaranteed.

For top professors who have more experience, earning $200k or more is not unheard of, but it is not common. Salaries in this range or higher are probably most realistically achieved by looking to advance within business schools but, again, such compensation levels are not common among professors with a true financial planning focus.

Maintaining a financial planning practice while in a tenure-track role is doable, but it certainly presents its own challenges. Ideally, advisors would probably want to outsource as much as they can (or have partners) to make it work.

Picking up ad hoc planning work may work particularly well (e.g., doing planning or hourly work when you have an opportunity) and may help an advisor stay connected to the practice while also working primarily as an academic. But you have to be realistic about your potential to get your research, service, and other requirements fulfilled to get tenure and then move up as a tenured professor, while also running a financial advisory business.

Some programs may also be more open to this than others. All else being equal, universities with existing faculty who have already successfully managed their outside business while fulfilling their duties as a professor will likely be more receptive to the idea (and you generally will need to get permission for outside business activities, so don’t neglect to have that conversation during an interview!).

Business schools also seem to be generally more receptive to the idea, as they like faculty to be engaged in consulting and outside real-world business work that translates well to the classroom.

Programs within research universities but outside of business schools or core financial planning programs will probably be the least receptive to this idea. This is likely due to several reasons: (a) they’ve probably just never seen it done, and it does not sound feasible to them, (b) these programs value real-world experience less and are more focused on research, and (c) many programs outside of business schools rely more heavily on grant-writing for funding and would want you to be spending much of your ‘free time’ doing that.

Further Considerations For Tenure-Track Positions Within Research Universities

Universities are very hierarchical in nature. Every field is going to have its top programs (often Ivy League or comparable universities), and graduates from those top programs are going to have the best shot at tenure-track positions within their fields.

However, these programs typically graduate more students than there are jobs for, so there’s going to be some cascading in which individuals who didn’t receive jobs at these top institutions move down a tier and compete for jobs at that level.

Financial planning programs are somewhat unique in that most programs are still so young that the field is nowhere near as saturated as many. While financial planning positions at research universities and within business schools are still highly competitive and hard to come by, it is nowhere near as competitive as established fields such as finance, economics, or psychology.

For some perspective, in their book Cracks in the Ivory Tower, Philip Magness and Jason Brennan note that in 2015 over 55,000 students in the US received a doctorate degree from one of 432 institutions offering such degrees. And while not all of these students who received their doctoral degrees intended to go into academia, only about 7,400 reported having an academic job following graduation.

For some perspective, in their book Cracks in the Ivory Tower, Philip Magness and Jason Brennan note that in 2015 over 55,000 students in the US received a doctorate degree from one of 432 institutions offering such degrees. And while not all of these students who received their doctoral degrees intended to go into academia, only about 7,400 reported having an academic job following graduation.

If we use this as a base rate (at least initially, some of those students may secure jobs in the future), that implies that less than 14% of Ph.D.’s across all universities initially end up with academic jobs. While I am not aware of any published statistics regarding the outcomes for Ph.D. job seekers from financial planning programs (which is likely biased by the fact that some students in financial planning Ph.D. programs want to be practitioner-scholars and do not want to pursue an academic career), anecdotally it seems that more than 14% of graduates who want academic jobs are currently finding them. Furthermore, the growth of CFP Board Registered Programs as universities seek to add this offering creates a lot of opportunities for employment that do not exist in other fields.

In fact, while there are only four CFP Board Registered Ph.D. programs, there are now over 150 undergraduate CFP Board Registered programs, which implies the level of saturation is very different than most of academia within financial planning. However, it is also true that some CFP programs may have few, if any, faculty with doctorates and may instead rely more on individuals with a Master’s degree and practical experience to teach.

Research Requirements For Academic Tenure-Track Positions In CFP Board Registered Financial Planning Programs

Tenure-track positions at research universities are generally going to have the highest research requirements. Both quality and quantity of research are going to matter, with different fields or departments potentially placing more or less weight on each.

The best way to roughly figure out what a given program’s research requirements are is to look at the publications of professors who have successfully earned tenure. There’s some chance they cleared the bar by more than was required, but at least you know they cleared the bar.

While there’s never a guarantee and there’s always some subjective element to tenure evaluation, within one of the CFP Board Registered Ph.D. Programs (Texas Tech, Georgia, Kansas State, and Missouri) I would guess that a relatively “safe” tenure dossier would average out to at least 3 publications per year with at least 1 publication per year within an indexed journal, which are journals that are indexed in different academic databases and that are considered to have higher peer-review standards than non-indexed journals (e.g., the Social Science Citation Index [SSCI] or Emerging Sources Citation Index [ESCI], although the former will count for more than the latter).

Among the core financial planning journals identified by Professors John Grable and Jorge Ruiz-Menjivar in 2014, indexed journals would include journals such as Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning (ESCI) and Journal of Family and Economic Issues (SSCI). Additionally, outlets such as Journal of Consumer Affairs (SSCI) and International Journal of Consumer Studies (SSCI) will tend to be highly valued in financial planning programs, although these journals may also publish research that is often less relevant to financial planning specifically.

The remaining “core” financial planning journals identified by Grable and Ruiz-Menjivar would all be good outlets for rounding out a candidate’s dossier and establishing a focused research agenda. These journals would include journals such as Journal of Financial Planning, Journal of Personal Finance, Financial Services Review, Journal of Financial Services Professionals, Journal of Financial Education, and the CFP Board’s new Financial Planning Review. Of these journals, Financial Planning Review may have a bit more upside from a tenure evaluation perspective since the aim of that journal is to be an indexed journal in the future, and the CFP Board is putting a lot of resources towards making this a quality journal. But that process will take some time, and it is unclear right now where that journal will ultimately land.

Opportunities For Financial Planning Faculty Positions Outside Core Ph.D. Programs

Outside of the core financial planning Ph.D. programs, there are a number of financial planning programs outside of business schools within research universities. Commonly, these programs are housed in areas such as Family and Consumer Sciences (or similar).

For faculty positions within these programs, research expectations are probably similar to those within core financial planning programs, with the exception that, at least in some programs, faculty who are unfamiliar with financial planning programs may discount financial planning journals, and you may have to focus more on publishing in indexed journals.

This may mean that faculty in these programs have to publish research that is a bit less relevant to financial planning specifically, or at least they will need to find ways to frame their research that will be of broader interest (in order to fit the interests of the non-financial-planning-specific indexed journals).

For those within business schools, schools often rely on some form of journal ranking list to assist in the evaluation. Some common journal lists include:

- UTD 24 (the University of Texas at Dallas’ list of top 24 journals in business research)

- FT 50 (Financial Times’ list of top 50 journals in business research)

- ABS Rankings (Academic Journal Guide published by the Chartered Association of Business Schools which contains 1,582 journals)

- ABDC Journal Quality List (list of 2,682 journals published by the Australian Business Deans Council)

The ABDC journal quality list is the most expansive journal quality list and will, therefore, tend to be used by lower-ranking business schools. The higher ranking the business school, the fewer journals that will typically “count” for promotion and tenure considerations in the first place.

For instance, at the most elite finance programs, faculty may heavily discount anything that is not within a top finance journal (Journal of Finance, Journal of Financial Economics, Review of Financial Studies), a top economics journal (Econometrica, American Economic Review, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Journal of Political Economy, Review of Economic Studies), or perhaps a top accounting journal (The Accounting Review, Journal of Accounting Research, Journal of Accounting and Economics).

Few financial planning faculty would likely find themselves needing to publish in the most elite finance or economics journals, but the higher the ranking of journals you can publish in, the more it will open up your career opportunities as an academic.

Interestingly, although I cannot think of any professors who necessarily fit the description, an alternative career path within a business school context for someone who is interested in publishing financial-planning-relevant research but also wants to be in a higher-ranking business school (outside of a CFP program), could actually be pursuing a Ph.D. (or research agenda) in marketing with a specialty in consumer behavior. Journals such as Journal of Consumer Research and Journal of Consumer Psychology both make the FT 50 list and regularly publish research on consumer behavior that is (or could be) highly relevant to financial planning. Furthermore, publications such as Journal of Consumer Affairs, which rank slightly lower but are still highly respected, would be valued in both a marketing department and a financial planning program.

Nerd Note:

The number of publications expected for tenure can vary quite a bit by field and department. The average of 3 per year number put forward above was specific to financial planning programs which are open to publications in non-indexed journals such as Journal of Financial Planning, but an average of 1 per year (or fewer) could be acceptable in programs if the publications are of sufficiently high quality or impact (of course, the same applies within financial planning programs, as well).

Some programs will be highly restrictive with respect to a journal’s field classification (e.g., finance vs. marketing), whereas others will not. Lower-ranking business schools may have lower quantity and quality expectations (e.g., 5 publications total of “C” or higher in the ABDC list regardless of specialty).

Again, your best bet for determining what is expected at a given school is to look at what tenured professors published during their probationary period (their tenure-track period).

Do You Need 15 Finance Graduate Credits To Teach In A Business School Finance Program?

One of the most pervasive misunderstandings regarding teaching CFP courses in a finance program (specifically, a finance program within a business school, not simply a financial planning/CFP program outside of a business school) is whether you need to have 15 graduate credits to teach in a program.

Much of this confusion stems from different academic accreditation requirements. Generally speaking, the “15-credit rule” does apply within Business schools accredited by the Accreditation Council for Business Schools and Programs (ACBSP), but it does not necessarily apply to those accredited by the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB).

AACSB Business School Accreditation

AACSB accreditation is more common than ACBSP accreditation among higher-ranking business schools. It was originally founded as a consortium among elite business schools (e.g., Harvard, Yale, Penn, Columbia, etc.), but has expanded to now accredit over 780 schools worldwide.

There are two key considerations that help clarify the 15-credit rule with respect to AACSB accreditation: (a) AACSB universities set their own standards for defining whether a scholar meets the standards to be a “Scholarly Academic” (“SA”, which is an important status to attain because schools are not going to want to offer a tenure-track position to someone who is not academically qualified), and (b) anyone who earns a doctorate from a university with an AACSB-accredited business school (even if that doctorate comes from another department of the university outside of the accredited business school itself!) is generally automatically qualified for Scholarly Academic status for 5 years after graduation within AACSB programs.

What this means is that there is no requirement, necessarily, that a finance faculty member in an AACSB school has any graduate education in finance. If you earn a doctorate from a financial planning Ph.D. program (Georgia, Kansas State, Missouri, or Texas Tech), from AACSB’s perspective, you will have automatic status as academically qualified for 5 years after graduation because all of those universities also have AACSB-accredited business schools under their university umbrella (even though it’s not where their financial planning programs are housed).

The tricky part is that some specific schools may select to self-impose a 15-credit rule, so you may not be qualified at a particular school, but that is just a self-imposed rule by a particular university, and not a requirement of AACSB (further complicating matters here, in my experience, is that some faculty at AACSB think they have a 15-credit rule – perhaps because a previous school they were at had one or they think all AACSB schools have one when they, in fact, do not – so there can be confusion and it’s always good to reach out to a school and inquire about their specific requirements!).

Beyond the first five years of automatic status as a Scholarly Academic, a scholar must then meet a program’s specific requirements for qualification, which is almost always going to be based on publication requirements but might also include a credit hour rule. (Note: AACSB universities in the south appear to be more likely to have self-imposed 15-credit rules.)

Notably, this consideration is really only relevant for individuals within AACSB schools who want tenure-track positions (those that would need to be classified as SA for accreditation purposes), as those who may want to be full-time instructors who can more easily be classified under alternative categories without causing accreditation issues (e.g., Practice Academic [must have a Ph.D.], Scholarly Practitioner, or Instructional Practitioner).

ACBSP Business Education Program Accreditation

While also a well-respected accreditation institution, ACBSP emerged in 1989 with the purpose of accrediting business education in community colleges and more teaching-focused institutions (whereas AACSB was historically more focused on research-focused business schools). ACBSP accredits about 3,000 programs worldwide.

Unlike AACSB, accreditation under ACBSP does have a 15-credit rule that applies more generally to all faculty (both tenure-track and non-tenure-track). There is some nuance here related to the course being taught and the faculty mix, but the bottom line is that graduates from a core financial planning Ph.D. program will run into credit hour issues unless they have taken at least 15-credit hours of graduate-level finance coursework “in-field” (e.g., finance).

15-Credit-Hour Conclusion

Given that the 15-hour rule is applied by some AACSB programs and applies to all ACBSP programs, students who want to maximize their career opportunities should strongly consider taking at least 15-credit hours in finance within a properly accredited program.

That said, it shouldn’t be assumed that this is a requirement for those who want to teach in an AACSB program, as it is more often not the case that you need 15 credit hours so long as you otherwise meet a school’s requirements for classification as a Scholarly Academic. And for those who aren’t specifically trying to teach within a business school, the dynamics of AACSB vs ACBSP accreditation and the 15-credit requirement are a moot point.

Ultimately, there are – and will likely increasingly be – many great opportunities to teach within a CFP program. For most financial planner practitioners, the best route to teaching is probably to consider part-time teaching of an occasional course as an instructor at a local university.

Fortunately, the hurdles you have to clear to be qualified for this type of teaching are the lowest (generally a Master’s degree will be sufficient, with potential requirements for credit hours “in field”), and it can still be a very valuable way to share your wisdom with future generations of financial planning professionals.

For those who are interested in more of a full-time academic career (with or without a financial planning practice alongside it), there are more considerations regarding credentials and fulfilling research and other requirements (depending on whether you are pursuing a full-time instructor or tenure-track professorship), but there is still tremendous opportunity to have a great career and contribute to the profession.

Excellent article, but I feel I need to add my two cents. I retired three years ago from full-time employment as a Senior Financial Advisor. I did not wish to leave the field altogether, and decided to teach on a part-time basis. I felt this might be a good option for me since throughout my career I have taught a variety of finance-related courses outside of my full-time work. Although I have fine-tuned my post-retirement assignments over the last few years, I have found the overall experience to be enriching. The financial rewards, from my experience, have been modest, however the money is secondary to remaining engaged in a field I enjoy.

Sincerely,

Kenneth Romanowski, CFP(R), CTFA, MBA

Ardmore, PA

I like that you covered this topic. While I wasn’t actively looking for a teaching opportunity, one kind of fell into my lap at my alma mater, which I’ve remained very involved since graduating. You hit the nail on the head with the amount of time commitment involved for creating a curriculum from scratch as a first-time lecturer, coupled with the realization that many of us want to be true advocates for the industry where we feel we need to be thorough (yet keep our material simple enough for the average person to absorb) and simultaneously accurate (so as to not be called out on any one of the 100 items we covered during the semester by someone who went down a rabbit hole on a particular subject matter which isn’t necessarily our strong suit).

I will say the experience has been personally rewarding to me, as I’ve had an opportunity to share common knowledge to students in hopes a few of my nuggets of information will resonate with them as they continue on their life’s journey. While I never wanted to solicit my students in the classroom, I hope they come find me someday when they’re ready to seek out a qualified financial advisor.

The pay isn’t fantastic as a per-course instructor (only $4500 per 3 hour course per semester), yet it’s enough to pad my monthly budget as I ramp-up my portfolio as a newer financial advisor. There’s certainly not a quantitative value I can place on the exposure it will give me over time. Actually, the university just recently recorded me in a mini series covering personal finance topics of monthly budgeting, creating a savings plan, and understanding investments to be released in early 2021 to our alumni. That’s free marketing with exposure to a few hundred thousand alumni from the university. Although in reality, not everyone will see the videos, I couldn’t think of a better free marketing of myself to boost presence and credibility to so many people. And the videos didn’t need to get pre-approved by compliance since I already had my OBA approved as a lecturer and introduced myself as a lecturer and not affiliation with my BD.