Executive Summary

Starting an advisory firm is a bold risk, but even after it is established, growth introduces new and evolving risks that can undermine long-term sustainability if left unexamined. Advisors are trained to assess and manage risk in client portfolios, yet many give far less attention to the risks embedded in their own businesses. As with clients, the goal is not to eliminate all risk, but to align a firm's risk exposure with its goals and capacity – removing unmanaged or misaligned risks while embracing those that offer strategic upside. For firm owners, this requires clarity not only on where the risks lie, but on when to act, when to monitor, and how to prepare for inevitable disruptions.

In this article, Senior Financial Planning Nerd Sydney Squires discusses how advisory firm risk manifests across seven different dimensions, and how advisors can evaluate and integrate risk into their advisory firm in a thoughtful, strategic way as their firms grow.

First, profit margin functions as a firm's shock absorber and growth engine. A healthy margin (ideally around 40%) enables hiring, experimentation, and resilience in down markets, particularly for AUM-based firms that are exposed to market volatility. However, excessive profit retained at the firm level can become a retention risk if compensation growth lags. Introducing variable pay structures can both boost advisor well-being and more closely align team incentives with firm performance.

From there, advisors can consider the various risks and rewards of different service models. For example, recurring revenue provides predictability and stability – and at the same time, many advisory firms integrate AUM into their fee model, which scales well in bull markets, but compresses quickly in downturns. Blended models that combine AUM and planning fees offer more durability, especially when paired with stress-tested revenue scenarios.

Additionally, client types can pose different types of risk. Firms that depend heavily on a few large clients or underprice certain client segments create fragility in their revenue base. Much like concentrated portfolios, these risks require proactive diversification – either by gradually adjusting fees, 'graduating' misaligned clients, or growing segments with similar profiles. And in the realm of client acquisition, many solo or small firm advisors rely heavily on their own time and energy for marketing, creating a bottleneck as the firm scales. As the firm grows, this advisor-centric approach becomes unsustainable. Shifting to scalable marketing channels, outsourcing, or delegating to team members reduces dependency on the lead advisor and lowers long-term acquisition costs.

Finally, advisors may consider the risks inherent in their team structure and capacity. If a firm waits too long to hire, it risks burnout and turnover – yet hiring prematurely also introduces cashflow stress. At the same time, as the firm grows, it is easy for processes to increasingly exist in 'just' one advisor's head. This, in turn, creates a severe risk of turnover or leave of absence! Without process documentation and cross-training, firms are vulnerable to knowledge loss and inconsistent service. Establishing regular process reviews and redundancies improves team resilience and allows firms to scale more confidently.

Ultimately, the key point is that none of these types of risk is inherently bad. Rather, the challenge is for advisory firm owners to embrace 'their' risk that best aligns with their goals. Strategic use of guardrails, backup plans, and market stress testing can help firm owners make more confident and strategic decisions over time. Further, reducing low-reward risks while doubling down on growth-aligned ones allows advisory firms to scale more sustainably. Advisors who understand and intentionally shape their firm's risk profile are better equipped not just to survive, but to grow something uniquely molded to their long-term vision!

Advisors spend an immense amount of time discussing risk with clients – after all, risk management is one of the key areas of financial planning. Do they apply the same attention to detail to their own risk decisions as business leaders/owners?

A little more detail: a client's risk tolerance is a fundamental part of how advisors create the plan for their clients. Advisors are often managing both to a client's risk tolerance and their risk capacity: how much market volatility they can emotionally endure (or ignore) vs. how much market volatility their retirement plan and other goals can withstand. Whether this risk tolerance is expressed through a questionnaire, a synchronous conversation, or some blend of the two, a client's relationship to risk is something that is explicitly and implicitly revisited throughout the length of the planning relationship. The client's relationship with risk will evolve as their career, retirement, and other life goals – sometimes in predictable ways, sometimes in surprising ways.

Many people think they have a high-risk tolerance until they realize that high volatility doesn't only mean great upsides, but also sharper downsides – or they have low risk tolerance, yet may have their portfolios overweighted in their employer's stock. Yet these inconsistencies are challenging to capture in both an official assessment... or self-assessment. For example, this psychology study on how men and women assessed their own risk tolerance found that men tended to overstate their tolerance, whereas women understated theirs (an interesting counterweight to the typical risk tolerance gap between men and women, in which men tend to score higher, and women score lower). In short, people often struggle to articulate their own risk tolerance well – both due to factors such as survivorship bias, lack of experience in certain markets, or the money script a person uses to define their own values (even if they don't follow it all the time).

While there is plenty to say about client risk tolerance, the framework also applies for advisory firm founders.

Do Advisory Firm Founders Evaluate Risk Well? Should They?

To begin assessing the risk profile of an advisory firm, it's worth acknowledging a key fact up front: starting a firm itself is a risky decision – nearly half of all businesses fail in their first five years (although it's difficult to assess the success rate for advisory firms, the U.S. Bureau of Labor & Statistics suggests that "finance and insurance" businesses on the whole followed this trend). For firm owners, every decision is a balancing act of risk capacity, risk tolerance, and overall goals. These decisions become easier once an advisory firm has established the client base and capital to have a greater margin ... and margin for error … but the risks never disappear entirely.

But when advisors talk about risks with clients, it's rarely about removing all risk – that can't truly be done. It's more about right-sizing risk for the client's priorities and goals. Some clients may have a greater appetite for job risk, reaping both higher compensation, but also working in more turbulent industries. Other clients may be entrepreneurial and willing to take on additional debt to achieve their goals. Even within investments, while some risks can be diversified away, many clients are willing to consciously take on additional risk to align with their values or achieve their goals. Advisory firm founders face similar dilemmas: some risks are inherent, while others are undertaken in order to achieve the firm's specific priorities and goals. No decision is completely risk-free or guaranteed to work out, from choosing a fee structure to deciding whom to hire. There is always a degree of thoughtfulness to understand the risk being undertaken … and a degree in which options have been vetted as much as they can be, and a decision just has to be made!

However, just as clients tend to overlook or misunderstand the risk they may 'actually' be undertaking, so too can advisory firm owners. In some ways, as noted above, this is a necessary attribute of all entrepreneurs… and in others, it's possible to dangerously understate the amount of risk that has been undertaken, especially with the many pieces of the firm that are moving in conjunction. For example, imagine a small advisory team that has had an influx of clients, and everyone's capacity during the workday is tight. The firm's profit margin is high, but a few team members are locked in a place of high stress, placing them at risk of burnout – and at a small team, any team member quitting or even taking prolonged leave can create a domino effect of stress, burnout, and limited capacity.

So the advisor opts to reduce the risk of turnover by hiring a new employee – a risk in itself. If the employee is a good fit for the role and firm, then the team's stress eventually declines, and the profit margin will eventually recover as the lead advisor is able to delegate, creating space for additional clients and/or deeper service.

Risk is not a bad thing in itself. Much as how, with clients, the answer is not to 'opt out' of risk (which is, ironically, risky in itself!), as risk is a necessary component to return. Yet there are some areas where advisory firms may be hyper-aware of risk being undertaken … and other spots that are ignored, or that can inadvertently impact other areas of the firm – much as how risk is not so much about an individual asset, but about the portfolio as a whole.

So, the challenge to advisory firm owners is to right-size their risk exposure: eliminating the 'bad' risks, while reinvesting into the higher upside risks that align with the firm's long-term goals.

Seven Dimensions Of (Advisory Firm) Risk

Risk has many dimensions at an advisory firm, ranging from marketing to team management to more traditional metrics like profit margin. As is the case with risk itself with investments, some of these dimensions are in tension. Again, no risk is inherently bad, but it is important for advisory firms to 'choose their risk' and consider what strategic components they are undertaking that may make their road ahead more challenging – whether it is a temporary added risk or a long-term part of the business structure!

Profit Margin

Profit margin is essential in general, but perhaps especially at advisory firms that charge based on some component of market performance. Profit margin gives advisory firms space to hire, explore, and invest in new offerings, and acts as a buffer against unexpected mishaps.

In general, it's hard to have 'too much' profit margin; True Ensemble's Data Insights on 2025 Growth and Profitability suggests that around a 40% operating profit margin is advisable. Firms that are actively growing and reinvesting profits may be as low as a 25% operating profit margin; slower-growing firms are more likely to be at or above 40%. Overall, a healthy profit margin is especially crucial for firms that largely rely on AUM for revenue, since they are not only dealing with 'typical' business risk, but also market risk!

On the other hand, there is a chance that the profit margin of a firm is 'too high' if a firm has an advisory team and the revenue isn't being redistributed to employees at a satisfactory pace. If growth opportunities and pay increases don't present themselves, then that can ultimately create some level of employee retention risk.

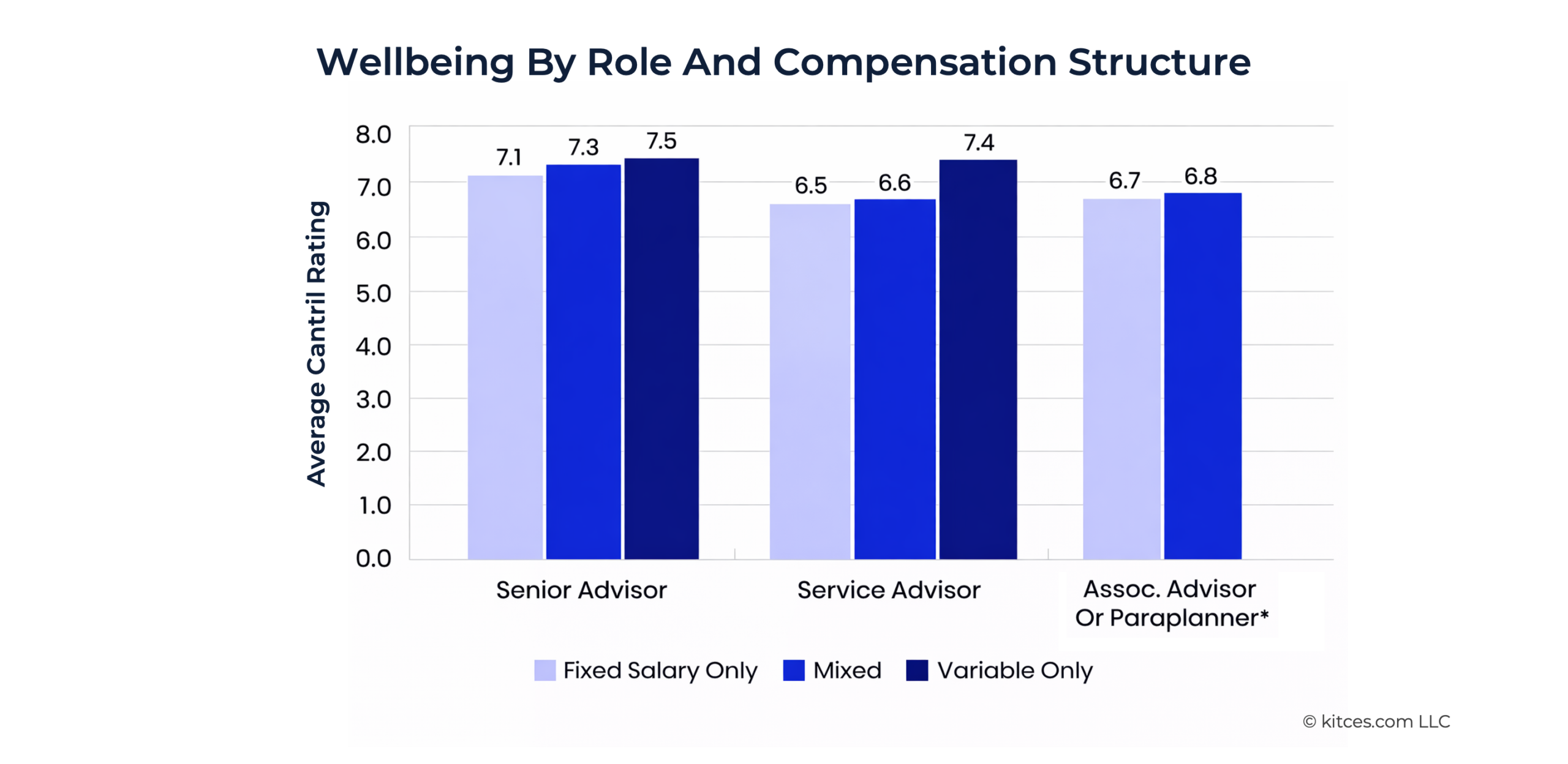

While some of this comes down to higher base pay, this is also an area where variable pay can be especially powerful, especially if the firm wants to incentivize employees to help the firm grow. In fact, Kitces Research on What Actually Contributes To Advisor Wellbeing indicates that variable pay is highly correlated with a team member's overall wellbeing. There is a 6% difference in levels of wellbeing between a fixed salary senior advisor and a variable only senior advisor.

Some of this correlation is because variable pay is also associated with high levels of autonomy and other factors that boost advisor satisfaction. But variable pay also increases the average pay employees receive – even across similar roles with similar levels of experience - that an advisor receives. A well-structured incentive pay structure can incentivize employees to remain focused on growing the firm… while minimizing revenue risk to the firm during tougher quarters/years.

About Kitces Research

The Wellbeing Study is one of four original scientific studies – on advisor wellbeing, advisor technology, advisor productivity, and firm marketing – conducted by Kitces Research and shared with Kitces.com readers on a rotating schedule every two years. The most recent Kitces Research study is our look at The Technology That Independent Financial Advisors Actually Use and Like.

The Wellbeing Study is one of four original scientific studies – on advisor wellbeing, advisor technology, advisor productivity, and firm marketing – conducted by Kitces Research and shared with Kitces.com readers on a rotating schedule every two years. The most recent Kitces Research study is our look at The Technology That Independent Financial Advisors Actually Use and Like.

Recurring Revenue

The spectrum of recurring revenue risk is fairly straightforward (especially compared with other dimensions of risk). Simply put: the greater portion of an advisory firm's fees that are recurring, the easier it is to project both revenue and revenue growth consistently. Conversely, one-time fees pose much higher levels of risk in advisory firms. This is especially true for one-time clients who may not re-engage after receiving the advice they need, which means the advisor has to continually prospect just to maintain revenue.

On the other hand, if an advisor mainly offers one-time plans, they also don't have to worry about clients who may not be a viable long-term fit for the firm. Many firms end up adjusting their planning fee (and their client base) – especially after their first few years, when they need to onboard almost any client to ensure that they can bring in revenue. Then, as the firm is viable and begins to grow, the firm must decide what to do with the early clients who took a bet on a new firm… but may not be able to afford the new fee.

Advisory firms and owners need to keep themselves afloat and remain profitable… and this is also a stressful situation for both advisors and their early clients, which can be reduced or at least mitigated by some one-time planning fees when the firm 'just' needs cash flow!

Revenue Sources

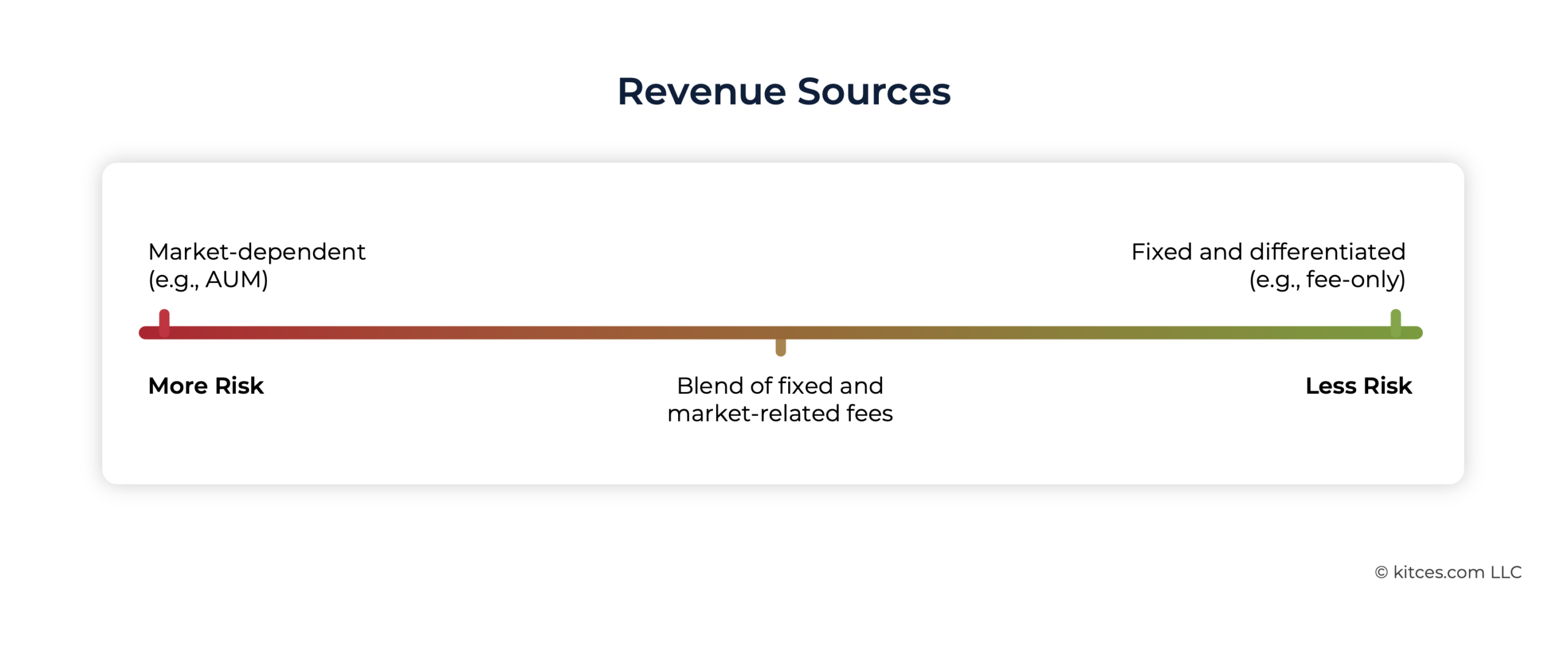

The current industry norm is for financial advisors to charge as a percentage of assets under management (AUM), which has several key benefits: namely, as the stock market goes up, so too do an advisor's fees. However, tying a firm's revenue to market volatility presents its own risks. Prolonged slow markets can make it challenging for a firm to scale at the pace it's used to; for many firms, a recession would be disastrous. According to a study by the Ensemble Practice, the average firm in 2024 had an average operating profit margin of 39.2% - and nearly 42% of them were confident in their ability to survive with few adjustments to their business (typically, owner compensation). Which means, conversely, that 58% of advisory firm owners were less-than-confident in their ability to withstand market corrections without making serious adjustments!

The risk that advisors are deciding between in their fee structure can be expressed as such: Technically speaking, having a fixed fee would be less risky. However, for a fixed fee to be less risky in the long term, advisors need to increase their fees regularly to at least keep pace with inflation.

In general, for some advisory firms, the better balance may be a blended fee charged on both AUM and a basic planning fee to insulate the firm somewhat from market turbulence. Just as client portfolios are stress-tested against prolonged bear markets (often using historical market data), advisors may test their fee model against different markets to determine a firm's 'true' risk.

Revenue Differentiation

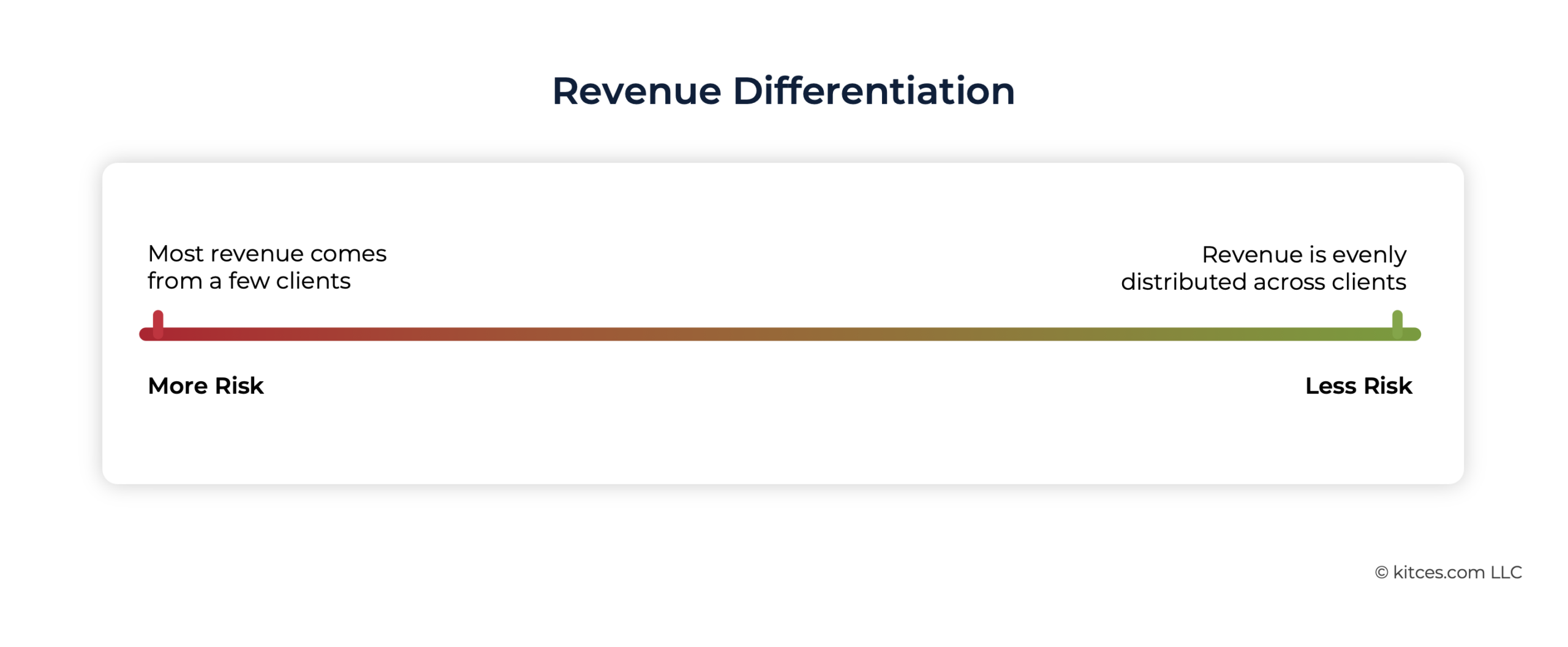

In many advisory firms, it is normal to have some level of fee differentiation, either due to client complexity or the size of the portfolio being managed. While this is very normal – and often a part of trying to move 'upstream' to larger or different clients – it can present disproportionate risk. While advisory firms typically boast a high proportion of client retention (of above 90%!), The reality is that advisory firms may be facing a higher level of risk with some clients and others. If an advisory firm manages to charge all clients more or less the same thing, then that risk is reduced greatly. The goal is not to have all clients paying less than the advisor is worth, but instead to gradually raise advisory fees with time, either by moving 'upstream', right-sizing fees for all clients, or 'graduating' clients who cannot pay the minimum fee.

A good equivalent to this is a client's concentration risk. Say that a client has highly concentrated stock (likely from a current or former employer). At what level of concentration does the client's portfolio risk become untenable (20%? 50%?)? The advisor can't gradually 'sell down' their concentration risk (and a high-paying client is not such a bad problem to have!), but it may be a good prompt to plan for alternatives in case that client becomes unhappy. At minimum, firms may not want to assign fixed costs to revenue that comes in from a single client. Perhaps this prompts an opportunity to strategize how the firm might find more people like said client.

Client Acquisition Process

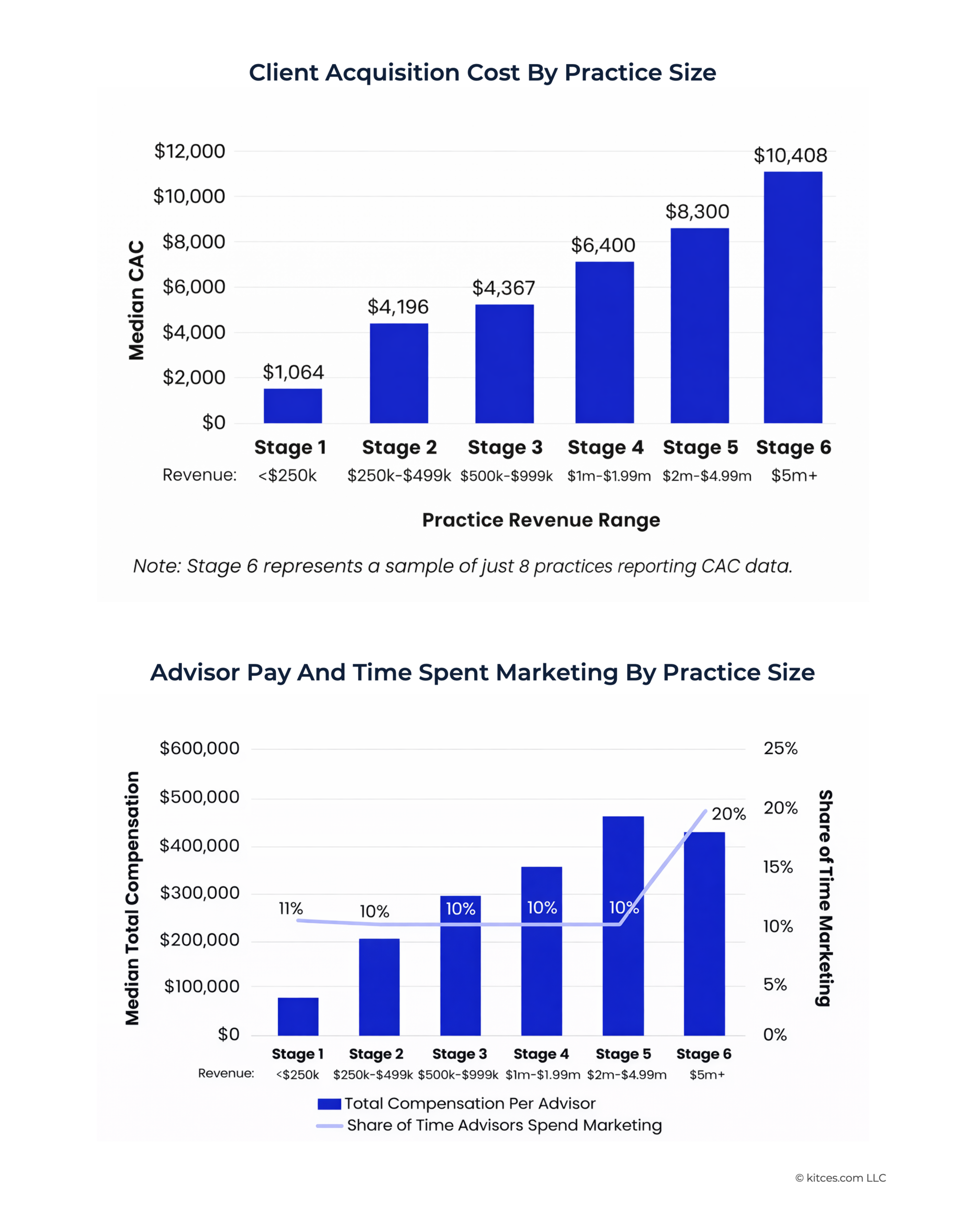

When starting their advisory firm, the lead advisor is essentially responsible for every role (at a new firm, there aren't really other options!). Even after the firm is established and the team starts to grow, it is very common for lead advisors to continue to do the prospecting in the client acquisition process. However, when the marketing begins to work, and an advisory firm and team grow, it can pose a significant risk for the firm if most or all of the machinations of marketing rely on the lead advisor's continued time and attention. Kitces Research on How Financial Advisors Actually Market Their Services finds that as firms grow, advisors spend more time marketing. To some degree, this is logical, especially as many advisors opt for time-based marketing tactics such as marketing events. These tactics are effective, particularly in the early days of the firm before an advisory firm starts to grow. However, once the firm starts to grow, the advisor's compensation typically increases as well. So, even if the amount of time that an advisor spends on marketing stays the same, these tactics become more 'expensive' in parallel with the advisor's time. Which then culminates in a higher client acquisition cost! These dynamics are illustrated below: when an advisor's core marketing strategy relies on their time, client acquisition cost will inevitably grow with the practice revenue.

Furthermore, marketing tactics centered on an advisor's time and attention are also harder to scale: an advisory firm can increase their spending on an online ad campaign, for example, but changing the lead advisor's time allocations tends to be more of a 'game of inches' as a firm matures, since their time is divided between more clients, team needs, and other demands of the business. If marketing cannot be delegated, at least in part, to someone or something, then a firm runs the risk of being unable to maintain the same pace of growth without putting in increasing amounts of time.

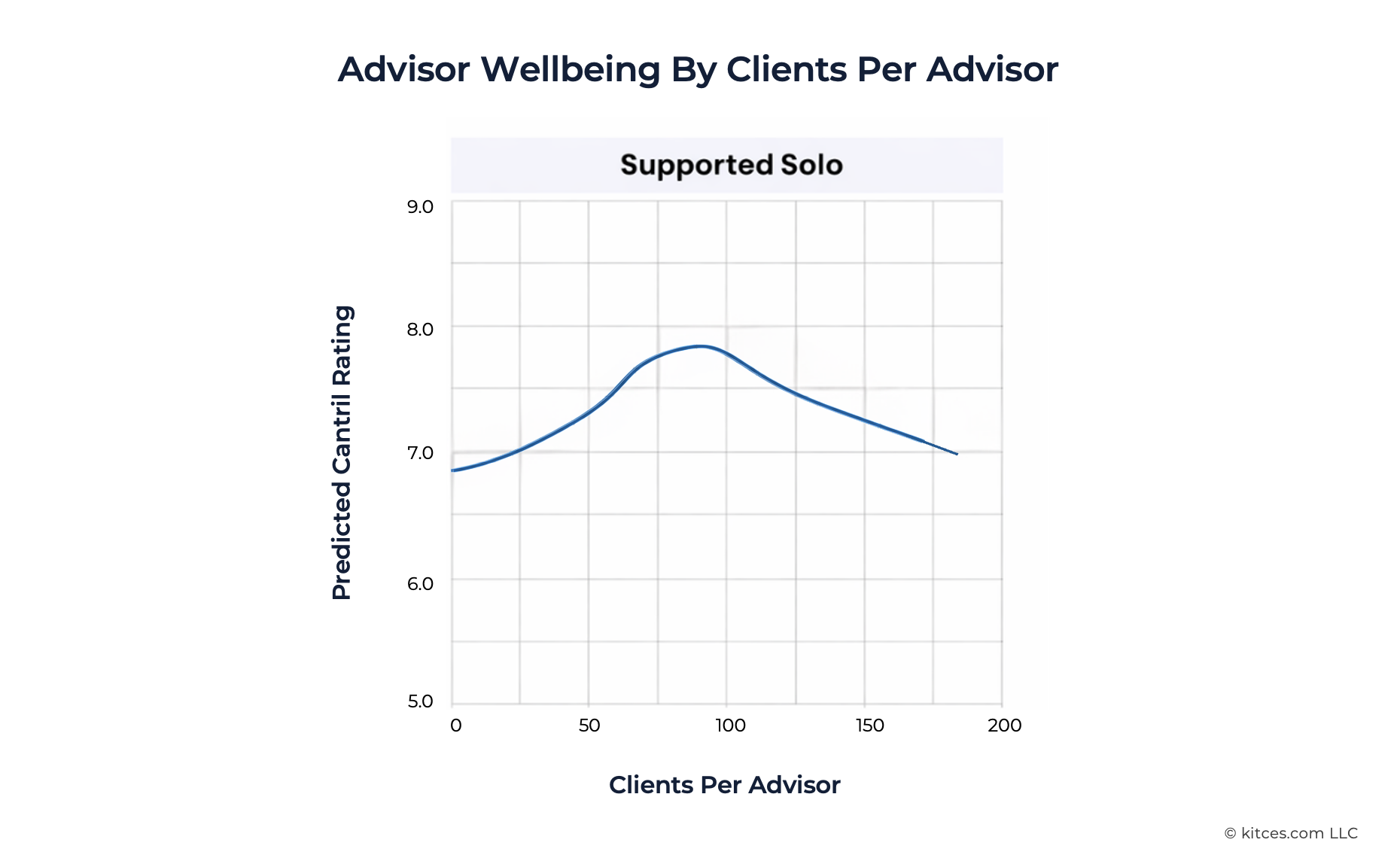

Firm Capacity For Additional Clients

Kitces Research on What Actually Contributes To Advisor Wellbeing points to the crossroads of the number of clients an advisor can serve, while still maintaining high levels of self-reported well-being. For an advisor with support staff, satisfaction typically peaks between 75 and 100 clients – more than that, and advisors either may not give the depth of advice they'd like, or they risk working too many hours to accommodate client needs.

If an advisory firm wants to increase the number of clients they serve, there will need to be a point when additional staff is hired – whether support staff or junior advisors, which inevitably means a hit to the profit margin. Furthermore, there is usually an 'in-between' phase after a new hire onboards when the firm has almost enough to keep them busy full-time… but not quite, leaving everyone with extra time while the firm's processes and client capacity catch up.

On the other hand, advisory firms 'late' in hiring run into the opposite problem: team members run into capacity issues, get stressed, and are at a greater risk of leaving, especially if the stress is prolonged. As an advisory team grows, the risk of either hiring or losing an employee will shrink, although they never disappear entirely.

Employee Dependency And Turnover

When an advisory team is small, it is common for processes to solely live in someone's head. It can be challenging to articulate processes well enough to 'just' delegate, let alone structure them in a way that team members can actually continue with 'business as usual' in their each other's absence.

Sometimes the risk of this is relatively small -some tasks can just naturally wait until someone returns! However, it can take an absence for gaps in cross-training to really appear, especially for tasks that the lead advisor 'used to' own, which may have evolved and grown since they were delegated to other team members. As such, it is important to not only have documentation explaining these steps, but also people who have been proactively trained and have had a chance to practice doing these processes while the person who normally leads on those steps is present.

If an advisory firm is just starting on process documentation, a once-a-year review of documentation of truly core processes is usually a good place to get started.

Understanding A Firm's Individual Risk

In sum, seven types of advisory firm risk have been presented. Notably, this doesn't include some of the more 'practical' types of risk, such as the risk of being sued and the need for E&O insurance. But it may highlight some of the risks that advisory firms face as they grow and scale. The bigger question is: how can firms understand their own level of risk, and what types of risk – once identified – require immediate action, and which may simply need to be monitored? Further, which selected risk exposures are necessary in order for the firm to grow as envisioned?

First, review these seven points and map out where the firm's risk actually falls. Whether there are some risks that are long-term (such as a certain type of fee structure to serve a firm's clients) or others that are short-term (such as trying to onboard staff to meet new client demands), this can be a helpful way to create a snapshot of the firm's current risk. Below is an example of how one firm might rate itself.

For example, the firm above has recently hired a new client service associate (CSA), so their profit margin has dropped, and the team's capacity has increased – which increases cashflow risk until the firm adds additional clients and increases its overall revenue again.

Once the firm has completed this self-assessment, it's time to get clear on what really happens if various types of risk go poorly. This can be similar to using Monte Carlo guardrails as a better way to illustrate risk: there is a difference between 'failure' as clients traditionally think about it (e.g., going bankrupt), and 'adjustment' (e.g., reducing spending). In the context of the advisory firm, it's worth taking a look at these higher-risk decisions and setting some preliminary guardrails in advance. What will the advisor do if their new hire doesn't work out? How is the firm braced for a market correction?

Nerd Note:

For advisory firm owners, there are a few personal 'guardrails' that can be put in place to further help insulate the firm against these types of risk, as is discussed in this episode of Kitces & Carl, such as maintaining access to a home-equity line of credit (HELOC) or taking options against market performance, that advisors may consider, especially in higher risk seasons of their firm. There are also other personal dynamics that can adjust a firm's risk: for example, if the advisor is the breadwinner, then that will inherently increase the risk of many business decisions vs. being in a two-income family!

Short-Term Adjustments

In the immediate term, profit margin is really the largest risk factor, given how it impacts so many other portions of the firm. Many firms have high profit margins, yet those same margins are also tied to market performance.

When it comes to changing profit margin, firms have a few options – although the main levers continue to be either making more or spending less. While advisors can work to increase their value and the quality of the product they deliver, or examine their expenses for possible areas of improvement – both valuable practices – it may be worth starting with the fee itself. Kitces Research on Advisory Productivity affirms that for most firms, it's less about AUM or planning-only or a blended fee structure (the various aforementioned risks of different fee structures aside); it's truly more about charging clients 'enough' to pay for their time, and charging their fees consistently without 'discounting' themselves. It is difficult to use accounting to work one's way out of 'too low' advisory firm fees.

In short, it is common for new advisory firms to underprice themselves while they get started. If it has been a few years since the firm's fee structure was moved upwards, this may be the signal to do so... especially if the aggregate number of clients has continued to grow.

Marketing Strategy

In the intermediate term, once the fees have been adjusted, much of the firm's risk can be mitigated by freeing up the lead advisor's time as much as possible for client-facing and prospecting calls. The two easiest components to focus on are administrative work and components of the marketing strategy – and both components lead to happier advisors, according to Kitces Research on Advisor Wellbeing. The less the marketing strategy relies on the lead advisor, the more likely it is that a firm can continue growing at a higher rate. Some firms may upskill their other advisors or staff, outsource parts of their marketing, find ways to automate portions of their marketing, or do some combination of the above. Reducing the demands of marketing on a lead advisor's time – and allowing them to spend more time on clients or in prospecting calls – is one of the key components of a high-growth.

Insulating Against Risk In The Long-Term Options By Focusing On Team Retention

In the long-term, it is hard to grow without a satisfied team that stays with the firm. All team members want the chance to grow, and especially to grow in roles that become closer to what they really 'want' in the long-term. This includes progress in both career opportunities and compensation – and, as mentioned earlier, variable pay can play a large part in long-term team motivation and retention.

Ultimately, regardless of the team role, it is rare that anyone other than the owner is a 'forever' employee. So while a plan to increase satisfaction and encourage retention is crucial, so too is ensuring that team processes and procedures are documented. This will make it possible for team members to cover other roles, whether in the long or short-term!

Ultimately, the key point is that business risk is a tool, and is certainly necessary to yield long-term growth and rewards. The conversations and principles that help clients better assess their 'real' risk apply aptly to thinking through business risk – especially when it's 'easier' to downplay that risk!

The reality is that risk is inherent to business ownership and leading a growing firm – and the secret is not to avoid it, but rather to use it strategically where appropriate. When possible, adopting a guardrail-like strategy is a helpful mindset for assessing and managing risk while allowing firms to insulate themselves from the worst long-term adverse outcomes. And the opposite is true, too: when risk pays off, advisory firm leaders are set up to reap the rewards!

Leave a Reply