Executive Summary

When a financial advisor transitions from one firm to another, they're often offered incentives by the new firm based on how much client revenue they bring with them. The challenge, however, is that advisors generally don't have the legal authority to simply transfer clients to a new firm. Because client relationships are technically "owned" by the firm – not the individual advisor – any transition requires clients to take action to shift from one firm to the other. This creates a host of challenges tied to client privacy laws and the advisor's contractual obligations to their former firms.

In this guest post, Isaac Mamaysky, Partner of Potomac Law Group and Cofounder of QuantStreet Capital, discusses the legal and compliance issues that arise when an advisor tries to bring clients with them to a new firm and the key considerations – including data privacy restrictions under SEC Regulation S-P and non-solicit clauses in employment agreements – that create complex dynamics and potentially conflicting obligations advisors must navigate to avoid violating privacy laws or breaching contractual obligations.

From a privacy standpoint, client data held by an RIA or broker-dealer is considered Nonpublic Personal Information (NPI) under Regulation S-P and generally cannot be shared with an unaffiliated third party without the client's consent – unless the firm's privacy policy explicitly allows it and the client has not opted out. Which means that if an advisor leaves a firm whose privacy policies don't permit such sharing, they can't take any client data with them, including names, contact details, or even knowledge that an individual was a client of the old firm. Furthermore, in states with stricter rules, such as California's "opt-in" privacy requirements, clients must affirmatively authorize information sharing at all times, adding another layer of complexity.

Although the Broker Protocol allows for the sharing of limited client contact information between firms, advisors and their firms are still required to comply with Regulation S-P. Advisors may only take information if their firm's privacy policies allow it and clients haven't opted out. In other words, participation in the Broker Protocol doesn't override privacy laws.

Further complicating matters, advisors may be bound by contractual non-compete or non-solicit clauses in their employment contracts with their old firm. These clauses typically prohibit advisors from encouraging clients to move with them to a new firm. So if an advisor is required to obtain client consent before transferring information to their new firm, they may be contractually prohibited from even asking for that consent. In other words, when privacy laws prohibit sharing information without consent, and contractual obligations prohibit asking for that consent, advisors risk violating either privacy law or their agreement with their previous employer!

Ultimately, the key point is that moving clients from one firm to another requires careful coordination across three fronts: Federal and state privacy laws, firm privacy policies, and employment agreements. While obtaining client consent is generally the safest approach, advisors must understand whether asking for that consent could violate their employment contract. While the rules can be complex, a thoughtful evaluation of the advisor's legal and contractual obligations, along with careful planning, can help manage their risk and increase the likelihood of a successful transition!

When a financial adviser prepares to sell their practice or transition to a new firm, the obvious goal is for clients to follow them – part of the sale price or negotiated payout is often tied to that very outcome. After all, the adviser's practice hinges largely on how many clients – and how much AUM – make the move. Yet, despite how essential client data is to ensuring a smooth transition, transferring that data isn't always straightforward.

While advisers may have built long-standing relationships with their clients, the wrinkle is that clients don't technically 'belong' to the adviser – they're clients of the firm the adviser is leaving, and they're free to either follow or stay put. Which means that taking client records, even with the best of intentions, could trigger violations of privacy laws or breaches of contract.

To further complicate matters, advisers often find themselves in a legal catch-22. Privacy laws like Regulation S-P (and opt-in state laws like California's) require client consent before nonpublic information can be transferred. But employment agreements often prohibit the adviser from seeking that consent before leaving. The result is a regulatory and contractual maze where each available option presents its own set of risks.

The Legal Landscape Of Client Data Transfers

Federal privacy laws, evolving state-level consent requirements, restrictive employment agreements, and the limited protections offered by the Broker Protocol all create overlapping legal considerations for advisers navigating a business sale or firm transition. Understanding how these layers interact – especially when the value of the transaction depends on client retention – can help advisers and their counsel evaluate possible approaches to preserve relationships without running afoul of privacy rules or contractual obligations.

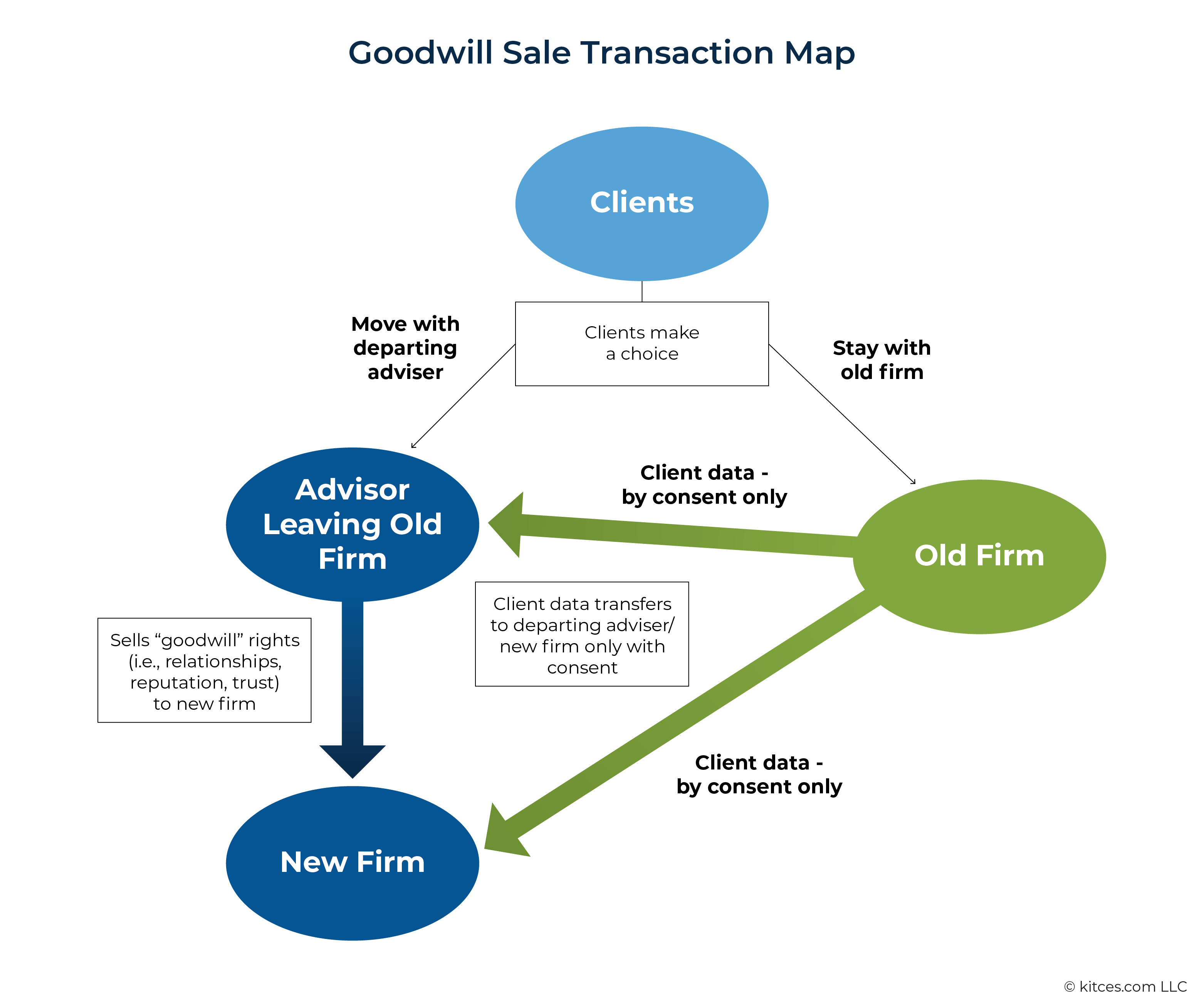

Because advisers don't own their clients, advisers can't sell client accounts outright. Instead, these deals are usually structured as a sale of goodwill – essentially, the adviser sells their personal relationships and influence with clients. In this context, the selling adviser is incentivized to persuade as many existing clients as possible to join the new firm. As a first step, they naturally want to take their client list and contact information with them upon departure. That way, they can reach out to 'their' clients, inform them of the move, and – when unimpeded by restrictive covenants – encourage them to join the new firm.

Once the sale closes, the adviser is typically paid out over time based on how many clients – and how much AUM and revenue – follows them to the new firm and remains there for a specified period. Even when the adviser's ultimate goal is retirement, they typically stay with the new firm for a few years to solidify client retention and maximize their payout.

Accordingly, the adviser needs access to client records at the new firm. These client relationships often span decades and include detailed notes and files – information that can be essential for continuing to serve clients efficiently and without disruption during the transition period.

How Regulation S-P Limits Client Data Transfers

Under Regulation S-P, adopted by the SEC pursuant to the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA), financial institutions must provide customers with a privacy notice explaining how their information may be shared, along with the opportunity to opt out of certain types of information sharing with unaffiliated third parties. This means that RIAs generally cannot share Nonpublic Personal Information (NPI) about a client unless the RIA's privacy policy explains how the client's information may be shared and the client does not exercise their right to opt out.

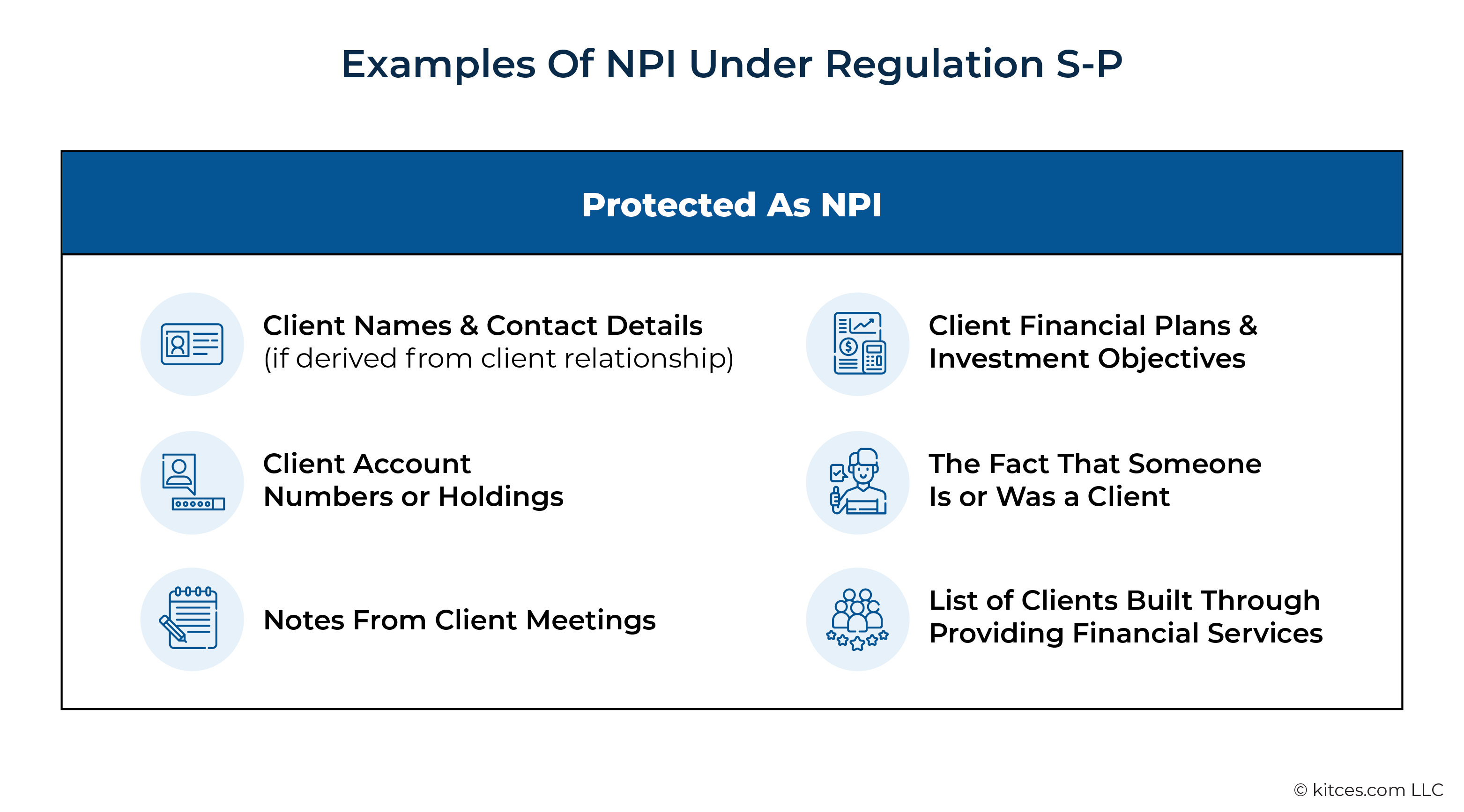

What Counts As NPI Under Regulation S-P

To understand how privacy rules apply in practice, it's important to clarify what Regulation S-P actually protects. The key concepts are Nonpublic Personal Information (NPI) and Personally Identifiable Financial Information – both of which have a specific legal definition.

Regulation S-P provides the following definitions of the two key terms:

Nonpublic Personal Information means:

- Personally identifiable financial information; and

- Any list, description, or other grouping of consumers (and publicly available information pertaining to them) that is derived using any personally identifiable financial information that is not publicly available information.

Personally Identifiable Financial Information means any information:

- A consumer provides to you to obtain a financial product or service from you;

- About a consumer resulting from any transaction involving a financial product or service between you and a consumer; or

- You otherwise obtain about a consumer in connection with providing a financial product or service to that consumer.

In other words, if the information relates to someone's finances, can be linked to them personally, was obtained as part of providing financial services, and isn't public, then it's probably considered NPI.

The Adopting Release to Regulation S-P explains that NPI includes customer lists, names, addresses, and phone numbers that are derived from information provided to a financial institution by a customer. Indeed, the very fact that an individual is a customer of a financial institution is considered NPI.

As the SEC wrote in the Adopting Release to Regulation S-P, the very fact that an individual has a customer relationship with a financial institution is, in and of itself, NPI. Some advisers have taken the position that something like a memorized client list, supplemented with publicly available contact information, is fair game – but the SEC disagrees.

We disagree with those commenters who maintain that customer relationships should not be considered to be personally identifiable financial information. This information is "personally identifiable" because it identifies the individual as a customer of the institution. The information is financial because it reveals a financial relationship with the institution and the receipt of financial products or services from the institution.

Per Regulation S-P Sec 248.3(u)(2)(c) itself, personally identifiable financial information includes: "The fact that an individual is or has been one of your customers or has obtained a financial product or service from you."

By contrast, NPI does not include publicly available client lists when the public source discloses the individual's relationship with the firm. But if an adviser knows a list of clients only because they've provided financial services to them – and their status as clients is not publicly available – then the list itself is NPI and protected under Regulation S-P.

That information cannot be shared with an unaffiliated third party unless the sharing is disclosed in the firm's privacy policy and the client did not opt out after receiving this disclosure.

In the context of a sale of goodwill, the departing adviser and their new firm are considered unaffiliated third parties. If the old firm's privacy policy doesn't allow information to be shared with them – or if the client opted out – then Regulation S-P prohibits the adviser from taking that information upon departure without the client's affirmative consent.

Why the "Sale Of Business" Exception Doesn't Apply To Advisers

The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) does contain several exceptions under which information can be shared regardless of opt-outs. Most relevant for immediate purposes, these include information-sharing in connection with a merger or sale of a business. At first blush, this might seem like welcome news to a departing adviser engaged in a sale of goodwill, but in reality, the exception only applies to the financial institution involved in the transaction. It does not apply to the financial adviser, because the clients are customers of the firm – not of the individual adviser.

This distinction was explained in the SEC administrative proceeding, Next Financial Group, Inc. While this opinion was decided in the context of a departing representative of a broker-dealer, its reasoning applies equally to a departing financial adviser of an RIA. The administrative law judge wrote:

[Rule 15(a)(6) of Regulation S-P] excepts disclosure of nonpublic personal information "in connection with a proposed or actual sale, merger, transfer, or exchange of all or a portion of a business or operating unit if the disclosure of nonpublic personal information concerns solely consumers of such business or unit."…

Under Regulation S-P, the consumer whose nonpublic personal information is being disclosed is a consumer of the brokerage firm; not a consumer of the registered representative who anticipates resigning from the brokerage firm… A registered representative who is not him- or herself a separate financial institution does not have customer relationships within the meaning of [Regulation S-P]. Such an individual lacks the standing to initiate a proposed transfer of one brokerage firm's business to another brokerage firm.

In other words, the "Sale of Business Exception" that allows the transfer of client information belongs to the financial institution (the old firm), not to the individual adviser. Even if the adviser built the book of business and maintains the client relationships, the clients are legally customers of the firm. Unless the firm itself is transferring the client data as part of a business sale or merger, the individual adviser cannot rely on the Sale of Business Exception to transfer client data.

Reviewing The Old Firm's Privacy Policy

As noted earlier, a financial institution may not disclose a client's NPI to an unaffiliated party – such as a departing adviser or their new firm – unless the client has been informed of that sharing practice and has not opted out.

This point was underscored in the SEC's Next Financial Group decision, which emphasized that departing advisers have a duty to review their employer's privacy policies to determine whether those policies allow the transfer of NPI to a new firm.

As the judge explained:

If a brokerage firm permits its transitioning representatives to disclose customer nonpublic personal information to successor brokerage firms, Regulation S-P requires the brokerage firm to inform customers that this disclosure could occur.

Clients must then have the opportunity to opt out of that type of information sharing. If the privacy policy lacks this disclosure, the departing adviser must obtain affirmative consent from each client before transferring any NPI. Likewise, if a client previously opted out, consent is still required.

Regulation S-P requires financial institutions to maintain a privacy policy that discloses how client data may be shared and provides clients with an opportunity to opt out of such data sharing. If the policy doesn't explicitly permit the adviser to share information with their new firm – or if a client has opted out – then the adviser must either leave the information behind or obtain affirmative consent.

State Privacy Laws Can Require More Than Regulation S-P

While Regulation S-P sets a Federal 'opt-out' standard, some states have adopted stricter privacy laws that require affirmative consent ("opt-in") before client information can be shared.

For example, California law states:

It is the intent of the Legislature…

- To ensure that Californians have the ability to control the disclosure of what the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act calls nonpublic personal information.

- To achieve that control for California consumers by requiring that financial institutions that want to share information with third parties and unrelated companies seek and acquire the affirmative consent of California consumers prior to sharing the information.

- To further achieve that control for California consumers by providing consumers with the ability to prevent the sharing of financial information among affiliated companies through a simple opt-out mechanism via a clear and understandable notice provided to the consumer.

While California is a standout example with especially strong privacy protections, it's not the only state with financial privacy requirements. Advisers must carefully assess the privacy laws in every state where their clients reside to determine whether affirmative consent is required before sharing nonpublic personal information. For advisers with clients across multiple jurisdictions, this may require a thorough, multi-state legal analysis.

Although many states do not currently impose opt-in requirements akin to California's, the landscape of state privacy laws is evolving quickly. In states that have not enacted more stringent standards, the Federal opt-out framework under Regulation S-P remains the governing rule.

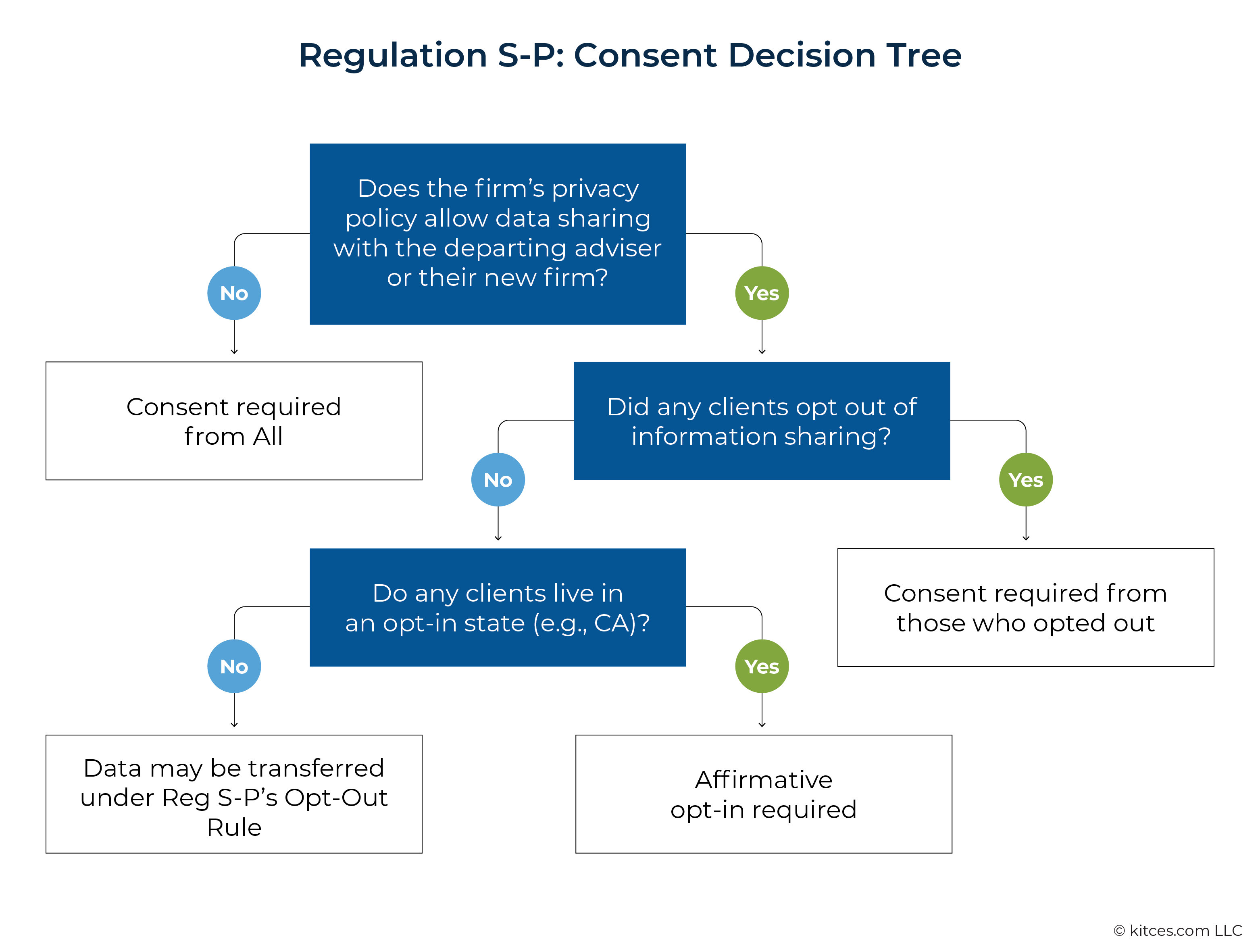

Taken together, these Federal and state privacy laws create a three-part framework for determining when client consent is required to transfer data, which involves assessing these factors:

- Whether the firm's privacy policy allows sharing client data with the adviser's new firm;

- Whether the client has opted out of such sharing; and

- Whether any state laws require affirmative consent before sharing Nonpublic Personal Information (NPI).

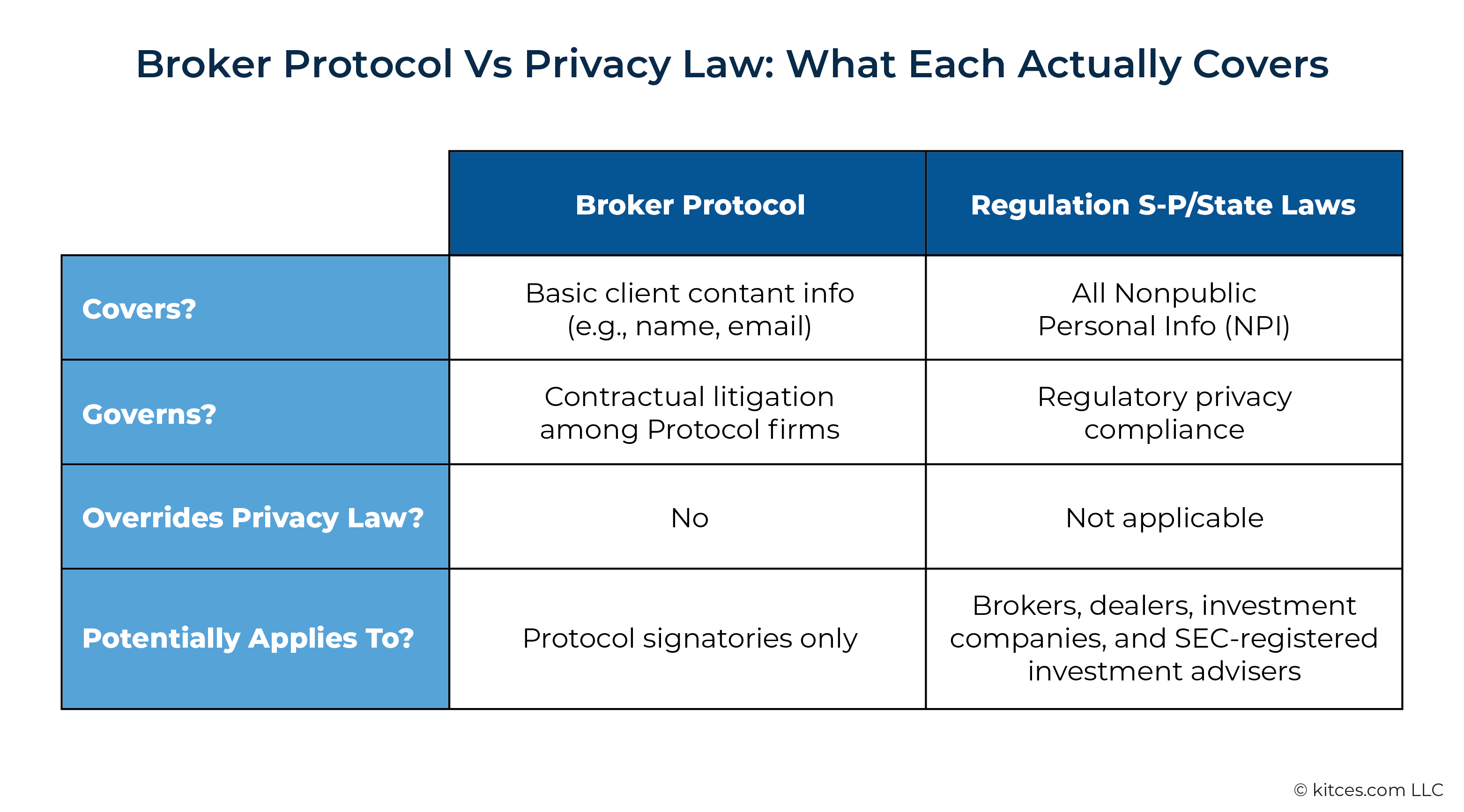

How The Broker Protocol Interacts With Privacy Law

Where does the Broker Protocol fit into all this?

The Broker Protocol is an agreement among its signatories that allows a departing representative from one member firm to take limited client contact information when moving to another member firm. Specifically, the departing individual is permitted to take names, addresses, phone numbers, emails, and account titles, but no other sensitive information or account details. The limited contact information can then be used at the new firm to seek client consent for the old firm to release more sensitive data or account-specific NPI.

As the Next Financial court ruling explains:

Under the Protocol, signatories agree not to sue one another for recruiting one another's registered representatives, if the representative takes only limited customer information to another participating firm and if the receiving firm does not engage in "raiding."… Resignations must be in writing and must include a copy of the customer information that the registered representative is taking to the new firm. The information may be used at the representative's new firm only by the representative, and only for the purpose of soliciting the representative's former customers.

However, it's important to understand that the Broker Protocol does not override privacy laws. It's simply an agreement designed to limit litigation over restrictive covenants between participating Broker Protocol members.

The departing adviser must still ensure that their actions don't violate Regulation S-P and any state privacy laws. As Next decision further explains:

…some, if not all, of the customer contact information transferred between Protocol signatories is nonpublic personal information. Nevertheless, before a violation of Regulation S-P could be proven, it would be necessary to determine whether the releasing firm's privacy policy informs customers of its disclosure practices and provides them a reasonable opportunity to opt out of the disclosure. This analysis must be done on a case-by case basis.

The key takeaway is that the Broker Protocol addresses contractual issues – it limits litigation over restrictive covenants between member firms – but it does not override Federal or state privacy laws. Even when operating within the bounds of the Protocol, a departing adviser must still ensure compliance with Regulation S-P and state statutes. Customer contact information taken under the Protocol may still qualify as protected NPI.

In short, the Broker Protocol lifts contractual restrictions, but it does not provide a regulatory shield. Privacy law compliance remains a separate and distinct consideration.

The Catch-22 Of Client Consent And Contractual Conflict

Even with a clear understanding of what the law permits, advisers often left without an obvious path forward. Moving client information from one firm to another can create significant legal risk. From the perspective of data privacy laws and SEC precedent, the ideal approach is to obtain affirmative consent from every client whose information the adviser plans to take with them upon departure.

However, while still employed, advisers are typically bound by contractual confidentiality, non-solicit, and non-compete provisions, as well as a common law fiduciary duty of loyalty to their employer.

And herein lies the problem: If an adviser seeks client consent before leaving, they risk breaching their duties to the old firm. But if they take client information without that consent, they may violate privacy laws or trigger SEC scrutiny. Either way, the adviser is faced with a dilemma that presents meaningful legal risk.

Contract Restrictions That Prevent Advisers From Seeking Consent

Notwithstanding the requirements of Federal and state privacy laws, many departing advisers are reluctant to request client consent before taking information from their current firm due to contractual restrictions. These may include confidentiality provisions, non-solicitation clauses, and non-compete agreements that limit an adviser's ability to act in anticipation of their departure.

In addition, advisers owe a fiduciary duty of loyalty to their firm while still employed – a duty that generally prohibits competition and other actions that would undermine the firm's interests or divert clients elsewhere.

The Memorized List Myth And Other Risky Workarounds

Some advisers attempt to sidestep the issue of taking client information by reasoning that they don't need to 'take' anything at all. The thinking goes: "Once I leave the firm, I can just Google my clients, find their publicly available contact details online, and reach out to them that way."

But this approach raises two important legal considerations.

First, as discussed above, Regulation S-P defines NPI to include any customer list derived from the adviser's provision of financial services. Even if the contact information itself is publicly available, the knowledge that these individuals are clients (i.e., the client list itself) – acquired through the adviser's role at the firm – qualifies as NPI and is subject to Regulation S-P protection.

Second, there are contractual implications. Many confidentiality agreements explicitly define client lists (including memorized ones) as confidential firm property. In these cases, an adviser who uses a memorized list to identify and contact clients – regardless of how contact information is located – may still be violating their agreement.

Client Files and Account Information

Beyond client lists, NPI also includes client files, account details, financial plans, and notes about client goals, investment timelines, and other circumstances. These records are often essential for maintaining continuity of service, but they're difficult to replicate at the new firm. They're also protected by Regulation S-P, state privacy laws, and most confidentiality agreements.

When it comes to this information, advisers typically have two choices:

- Take the information without consent and risk violations of state and Federal privacy laws; or

- While still employed, request client consent – and risk breaching employment contracts or the fiduciary duty of loyalty.

Without the cooperation of the old firm – whether through a contractual release, participation in the Broker Protocol (discussed earlier), or simple goodwill – there's no easy way to avoid both legal and contractual risk.

The Blurry Line Between Informing And Soliciting Clients

When helping advisers navigate these decisions, attorneys often conduct a 'liftout analysis' to manage the client communication process and evaluate the legal boundaries of pre-departure conduct. One area of focus is whether an adviser can inform clients about their departure without violating a non-solicitation clause. Case law supports the idea that simply telling a client "I'm leaving" – without encouraging them to follow – may not amount to solicitation or impermissible competition with the adviser's old firm.

For example, in Edward D. Jones & Co., L.P. v. Kerr (S.D. Ind. 2019), Edward Jones sued a former representative, alleging that his pre-departure communications breached a non-solicitation agreement. But the court rejected the claim, holding that advisers have a fiduciary obligation to inform clients of material changes, including their departure from the firm.

Still, this line quickly blurs. While telling clients "I'm leaving for another firm" may be defensible, the message begins to sound much more like a prohibited solicitation when the follow-up question is: "Can I take your file with me when I go?" These nuances need to be considered carefully during the liftout analysis.

Evaluating Risk: Frameworks For Legally Moving Client Data

Given the regulatory backdrop and contractual tensions at play, advisers considering a goodwill sale must carefully evaluate the legal risks before transferring any client information. While there may be no perfect solution, the frameworks discussed in the sections that follow can help advisers assess whether – and how – client data might be moved legally and responsibly.

A goodwill sale typically involves the adviser transferring relationships – not actual client accounts – which means clients must choose whether to follow. The graphic below illustrates this dynamic and the legal constraints around transferring data.

Regulatory Considerations: Can Client Data Be Transferred?

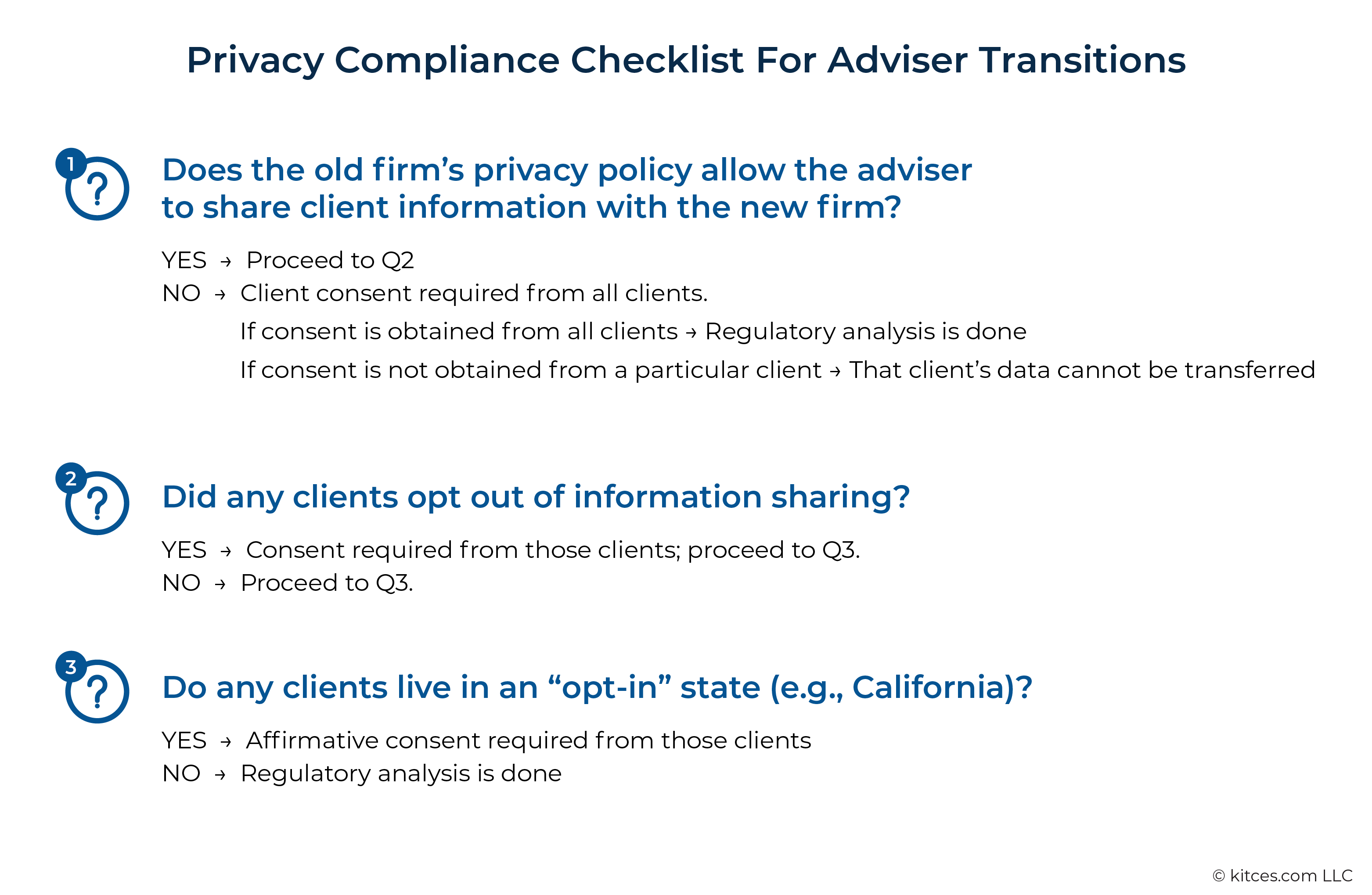

Before moving any client information, advisers must determine whether doing so complies with privacy laws and regulations. The following questions offer a practical framework to help advisers assess whether client data can be shared under Regulation S-P and applicable state privacy laws:

- Does the old firm's privacy policy allow a departing adviser to take client information to their new firm?

- If yes, proceed to question 2.

- If no, the adviser needs consent from all clients whose information is being transferred from the old firm. With affirmative consent from all clients, questions 2 and 3 become moot.

- Did any clients opt out of information sharing?

- If no, then proceed to question 3.

- If yes, then the adviser needs the affirmative consent of those clients to supersede their opt-out election. Then, proceed to question 3.

- Do any clients live in an "opt-in" state?

- If no, then the regulatory analysis is done.

- If yes, then the adviser needs their affirmative opt in.

Nerd Note:

Could a "negative consent" approach be sufficient in the Regulation S-P context? In other words, could a departing adviser notify clients in advance of their intent to transfer client information to a new firm, and proceed unless the client affirmatively opts out?

The SEC has recognized this type of negative consent mechanism in certain contexts, such as when an advisory firm is sold and client contracts are assigned to a successor firm. In that scenario, the SEC allows firms to provide clients with advance notice of the assignment and an opportunity to object, treating silence as consent. More broadly, Regulation S-P itself is built on a negative consent framework: Firms must deliver a privacy policy that discloses potential information-sharing practices and offers clients the ability to opt out. If the client does not opt out, then the firm may proceed as disclosed in the policy.

Whether this negative consent approach could apply when an individual adviser – not a firm – is transferring client information to a new employer is a question for another day. One could argue that if clients are fully informed of the intended transfer and given a reasonable opportunity to opt out, then the regulatory risks could be mitigated.

Ultimately, the sufficiency of negative consent in this context is an open question and likely depends on factors such as the specific terms of the firm's privacy policy, the nature of the client notification, and the applicable state privacy laws. A thorough legal analysis, and treading very cautiously, would be prudent before relying on a negative consent approach.

When considering the obligations imposed by Regulation S-P, advisers and their counsel would be well-served to consider the cautionary observation of the SEC's former Deputy Director of the Division of Investment Management. In his comprehensive compliance guide for investment advisors, Regulation of Investment Advisers, Mr. Plaze observes: "A number of cases under Regulation S-P have involved employees or executives of advisers (and broker-dealers) who have taken 'their' client files with them to new jobs. In each case, the SEC or court concluded that such transfer was prohibited by the privacy rules unless client consent was first obtained."

From a regulatory standpoint, consent is the name of the game. The safest practice for a departing adviser is to obtain affirmative consent from each client whose information the adviser plans to take upon departure. At a bare minimum, advisers have an obligation to obtain affirmative consent before taking any information about clients who have opted out of information sharing or who live in opt-in states.

Contractual Risk Assessment

In addition to analyzing regulatory compliance required by Federal and state privacy laws, advisers planning to join a new firm must carefully evaluate their contractual obligations and fiduciary duties to their current employer before transitioning client information or communicating with clients about the departure.

While privacy law presents a series of regulatory concerns for advisers changing firms, the legal analysis doesn't end there. That's because the agreements an adviser signs with their current firm can be equally limiting. Confidentiality provisions, non-solicitation clauses, and non-compete agreements (collectively referred to as 'restrictive covenants') are standard features in many advisory firm employment contracts. In addition, the common law duty of loyalty often restricts advisers from engaging with clients, discussing transitions, or taking any action that might be seen as competitive before officially departing. These restrictive covenants often reinforce those obligations and extend them far beyond the term of employment.

Each of these restrictive covenants serves a different legal function and carries its own risks:

- Non-compete clauses prohibit advisers from joining or starting a competing business within a certain geographic area and timeframe after leaving their old firm. Though often challenged and subject to state-specific enforceability limits, non-competes can delay an adviser's ability to serve clients post-departure.

- Non-solicitation agreements prevent advisers from directly or indirectly encouraging clients to follow them to a new firm. As discussed earlier, even factual or neutral language can be construed as solicitation depending on context.

- Confidentiality provisions typically define client lists, memorized information, and client financial data as proprietary firm property that continues to belong to the firm following the adviser's departure.

Taken together, these covenants form a contractual shield that firms use to protect their business from post-employment competition, solicitation, and use of confidential information.

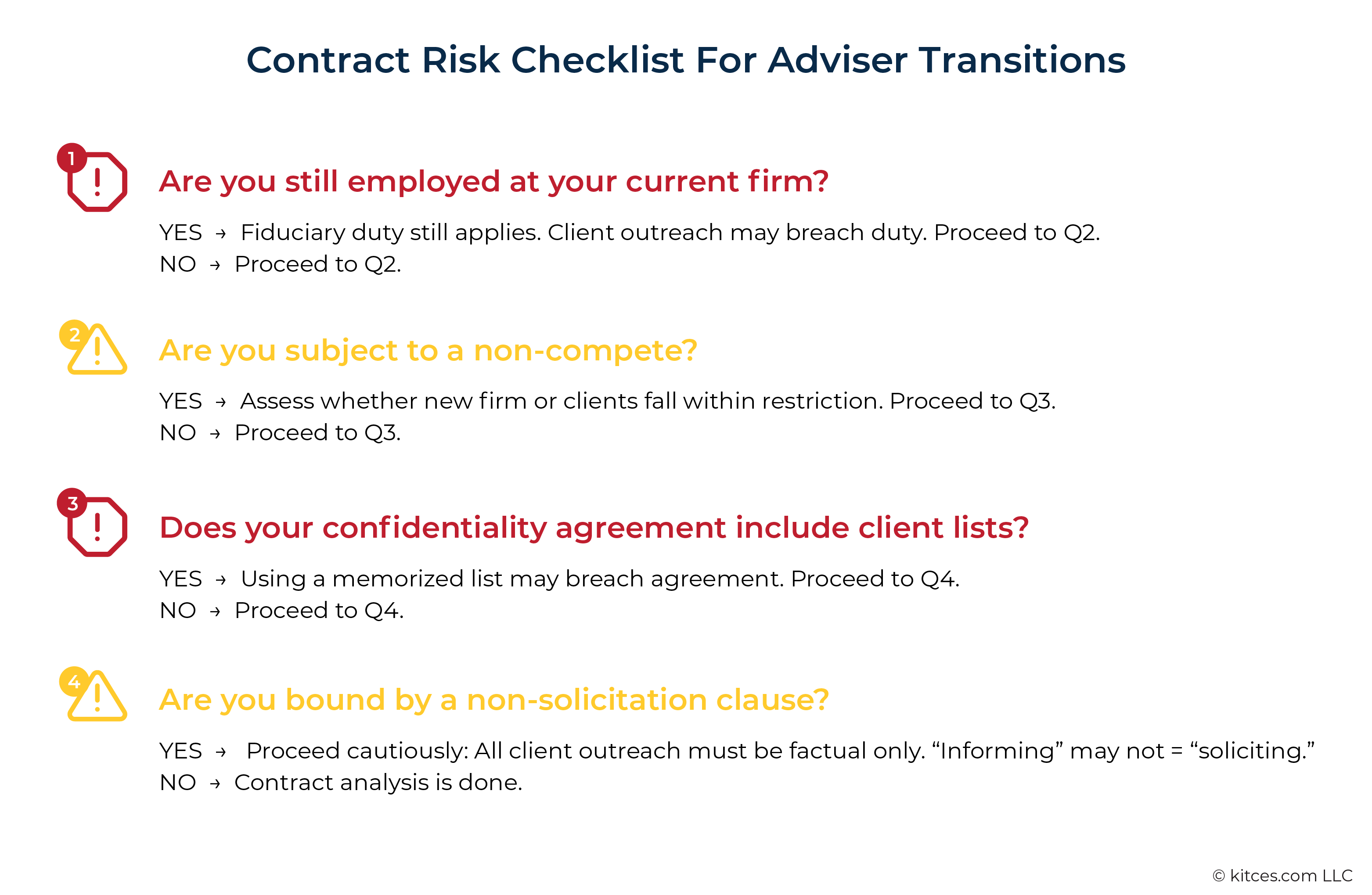

The following questions may serve as a practical framework to help advisers assess some of the relevant considerations:

- Is the adviser still employed and therefore bound by a fiduciary duty of loyalty to their current firm?

- If yes, understand the risk that preemptive client outreach, and seeking client consent for the movement of data, could be deemed competitive with the employer. Proceed to question 2.

- If no (e., the adviser has already left their firm), then the fiduciary duty is likely extinguished. Proceed to question 2.

- Is the adviser subject to a non-compete?

- If yes, determine whether joining the new firm or continuing to serve clients post-employment would trigger a violation. Proceed to question 3.

- If no, proceed to question 3.

- Is the adviser subject to a confidentiality agreement that defines client lists (including memorized ones) as confidential information?

- If yes, understand the risk that using a memorized list to find publicly available contact information, and then contacting clients post-employment, may breach the confidentiality agreement. Proceed to question 4.

- If no, proceed to question 4.

- Is the adviser subject to a non-solicitation agreement?

- If yes, assess how to approach client communication so it is considered factual/informational and not a solicitation (bearing in mind that even neutral language can be deemed a solicitation).

- If no, then the contract analysis is done.

When advisers navigate how to inform clients of their departure and seek consent for the movement of client data, they must carefully weigh these contractual obligations and fiduciary duties to minimize legal risk and avoid breaching their agreements.

For financial advisers transitioning between firms, the sale of goodwill is often a cornerstone of the transaction, but it is only one piece of a complex puzzle. While the adviser's relationships with clients are central to the deal's value, the actual client data belongs to the old firm, and moving that data raises complex regulatory and contractual issues.

The challenge lies in the overlap between what advisers must do under privacy laws (i.e., obtain client consent) and what they cannot do under contract law (i.e., solicit clients or disclose confidential information). Regulation S-P and state privacy laws impose strict limits on transferring Nonpublic Personal Information (NPI), with client consent serving as the legal foundation of any permissible transfer. Meanwhile, employment agreements and fiduciary duties to the current firm may restrict advisers from seeking that consent before they leave.

This tension often creates a significant dilemma for advisers: staying silent could comply with contracts but violate privacy obligations, while proactive client outreach may be legally required under privacy laws but contractually prohibited. And although the Broker Protocol may offer a limited safe harbor for taking basic contact information, it does not override privacy laws.

Ultimately, there is often no perfect solution advisers navigating a goodwill sale – only risk-managed pathways. The safest course remains to obtain affirmative client consent while carefully navigating restrictive covenants, firm privacy policies, and the evolving landscape of applicable state and Federal regulations.