Executive Summary

For many homeowners, moving to a new residence is a straightforward process of selling one home and buying another. But for clients who choose to keep their former primary residence as a rental, the decision opens a range of complex tax considerations – and, with them, planning opportunities. Converting a home to a rental property fundamentally changes how expenses are treated, how gains are taxed, and how future sales can be structured to maximize tax efficiency. Advisors who understand these rules can help clients navigate the timing of deductions, leverage the home sale gain exclusion, defer gains through 1031 exchanges, or even use multiple strategies in combination to minimize taxes on property that's converted to rental.

Once a primary residence becomes a rental, previously personal expenses may become deductible rental expenses. However, the timing of the conversion matters. Routine maintenance and repairs performed after the property is "available for rent" can often be deducted, but similar work done beforehand is generally considered a nondeductible personal expense. Depreciation also begins at conversion, using the lower of the home's basis or fair market value.

These upfront expenses – combined with potential delays in finding an initial tenant – can often result in a net loss during the property's early years. But rental losses are generally 'passive' and can only offset other passive income. For individuals with AGI under $100,000 who 'actively participate' in managing the rental, up to $25,000 of losses may be deductible against other income (with the benefit fully phasing out at $150,000). Consequently, documenting expenses and activities such as marketing, screening tenants, or making repairs is essential for maximizing their rental deductions.

Other tax planning opportunities can center on the $250,000 (single) or $500,000 (joint) primary residence gain exclusion under Section 121, which can remain available for up to three years after the home ceases to be a primary residence. Some individuals may also consider selling the property to a wholly owned S corporation (i.e., owned fully by themselves) before the three-year deadline. This can lock in the gain exclusion, reset the property's basis for depreciation, and preserve (indirect) ownership of the rental – though it may require careful structuring and strict adherence to sale terms to withstand IRS scrutiny.

For clients seeking to defer taxes – whether due to holding the property beyond the three-year gain exclusion window or realizing appreciation in excess of the Sec. 121 exclusion amount – a 1031 exchange can enable a tax-deferred swap into another investment property. And for clients who qualify for both the exclusion and a 1031 exchange beyond the exclusion limit, an "1152 plan" combines the benefits of Section 121 and 1031, offering a hybrid approach: By selling within the three-year window, pocketing the exclusion amount, and rolling the remainder into a like-kind property, clients can effectively 'cash out' the excluded tax-free portion while deferring the remainder. This strategy can be particularly useful for highly appreciated properties or for clients seeking to pass the property on to heirs with a step-up in basis.

Ultimately, converting a primary residence to a rental can unlock meaningful opportunities – but also potential tax pitfalls. Advisors can play a key role by helping clients maximize the deductibility of expenses, preserve gain exclusions, consider S corporation or 1031 strategies, and navigate passive activity loss limitations. By approaching the transition with careful tax planning and an eye on both short- and long-term goals, clients can transform a personal home into a productive rental asset in a way that aligns with their financial objectives and minimizes unnecessary tax costs!

When most individuals decide to move, it's usually a one-for-one transaction. They sell one property and move into another. But from time to time, when individuals decide to move and make a new home their primary residence, they may not want to sell the 'old' primary residence.

In some situations, individuals may be reluctant to sell their old home for financial reasons. The area may be 'hot' at the moment, and they may see renting their old home as a valuable income stream. Other times, the market may be down, and there may be a desire to wait to sell the old home until after the price of the home has rebounded.

In other situations, the desire not to sell an old home might be driven more by sentimental feelings. Perhaps the home has been in the family for many generations, and selling seems like a betrayal of family values. Or maybe there's a thought that one of the kids might want to move back in at some point.

Regardless of a client's motivations, choosing to turn a former primary residence into a rental can create unique tax consequences – and important planning opportunities. Advisors who understand the tax rules and recognize available strategies can help clients make informed decisions that align with both their financial and emotional goals.

How Personal Expenses Become Rental Expenses And Why Timing Matters

Once an individual turns their home into a rental property, it changes the nature of personal expenses to rental expenses. In some cases, this may amount to a tax preparer merely 'moving' the expenses from one form to another on the tax return (e.g., moving mortgage interest on the home from Schedule A as an itemized deduction to Schedule E as a rental expense). In many other situations, however, it may turn a previously nondeductible personal expense (such as painting the house) into a deductible rental expense.

Naturally, then, this shift means it also becomes much more important to maintain records of such expenses once the home is turned into a rental property. And to the extent that there are things an individual wants to fix before the property is rented, it can make sense to consider delaying such repairs until after they've moved to their new primary residence.

Nerd Note:

Potential repairs (or other maintenance) that could be deductible as a rental expense include repairing leaks, patching holes and painting, repairing heating or cooling units, servicing appliances, cleaning gutters, patching roofs, and other similar expenses that don't significantly extend the life of the property.

By contrast, other expenses that do extend the life of the property generally are not fully deductible and must be capitalized and depreciated over their useful lives. Such expenses typically include replacing a large portion of (or an entire) roof, installing a new heating or cooling system, installing new flooring, replacing windows, and installing new appliances.

Notably, if an individual makes repairs to their home while it's still their primary residence, those repairs are personal in nature – even if they're made because they'll 'need' to be completed to successfully rent the property. However, delaying such repairs until after moving out may delay the rental start date, which could result in lost rental income. That trade-off should be considered when deciding on the timing of any work.

Of course, this raises the question: when does a residence officially become a rental property? In other words, what triggers the shift from personal to deductible rental expenses? Technically, this point is generally determined by the date the property is "made available for rent". But, as with many things in the tax world, this can be a gray area – highly subjective and dependent on "facts and circumstances".

For instance, if an individual is still living in their home when a repair is made, the property is clearly not yet available for rent, and that repair would be considered a nondeductible personal expense. But what if the owner has moved out and listed the property for rent and then repaints the home? In such cases, the deductibility of the expense can depend upon whether the repair was truly necessary to rent the home, or merely helpful. Most homes, for instance, could likely be rented without a new paint job. Which means the repainting could be considered a deductible expense because the home was already available for rent before the work was done.

Once a primary residence is ready and available to rent, one key deduction that becomes available is depreciation. The starting basis for depreciation is the lesser of the homeowner's basis in the property, at the time it became available for rent or the fair market value at the time of conversion.

Often, individuals converting a personal residence to a rental property will incur significant upfront costs – repairs, maintenance, and other improvements to make the property more attractive to tenants. Couple these potentially large expenses with possible delays in finding a tenant, and it's not hard to imagine new landlords running a net loss on rental income for the year.

In general, rental income is considered passive income, and thus, a rental loss can only be used to offset other passive income. There are limited exceptions to this rule, however. Taxpayers with $100,000 or less in Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) who 'actively participate' in managing the rental (typically by owning more than 10% of the property and contributing to management decisions) can deduct up to $25,000 in rental losses against non-passive income annually. Additionally, taxpayers who qualify as real estate professionals may be able to deduct rental losses against other income, though they may still be subject to other limitations, such as the limitation on excess business losses.

Tax Planning Strategies For Converting A Home Into A Rental

Once a home is converted to a rental property, a range of tax planning opportunities come into play – particularly when the property has appreciated substantially in value or is expected to generate deductible losses. From leveraging the primary residence gain exclusion to structuring future sales for maximum tax efficiency, there are several strategies that may be worth exploring before any decisions are finalized.

Retain The Gain Exclusion By Selling Within Three Years

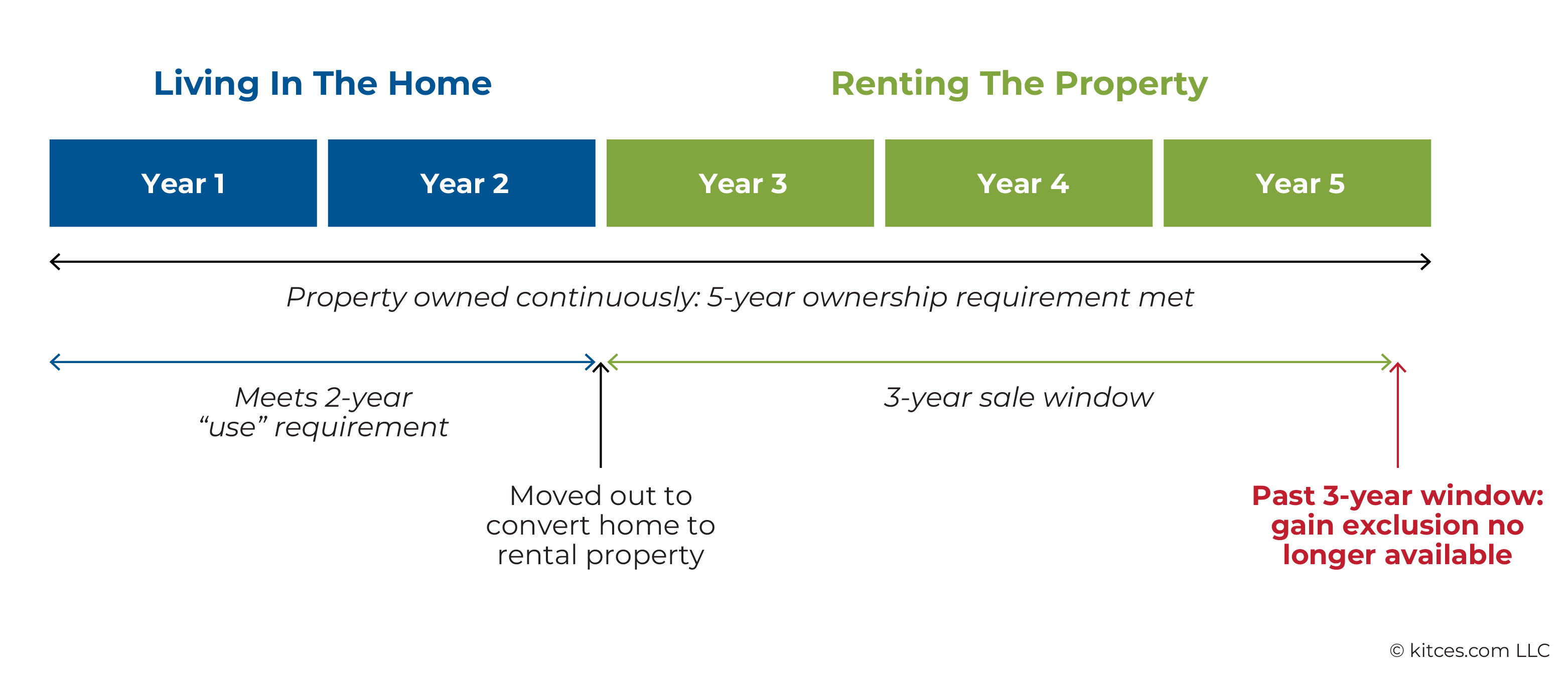

Recall that the gain exclusion of up to $250,000 for single filers or $500,000 for joint filers requires that the taxpayer meet the ownership and use requirements – generally having owned and lived in the home for at least two out of the past five years. Notably, there is no rule that prevents this exclusion from applying to a recently converted rental property, as long as the ownership and use requirements are still met.

Example 1 : Lois and Peter purchased a house on Spooner Street in 1999 for $300,000. Over time, the house appreciated substantially and is currently valued at $1MM. Recently, the couple inherited a property from Lois's parents closer to the beach, and after thinking it over for a bit, they decided to move in.

Lois and Peter aren't totally sure they'll love the new (inherited) home, though, so they want to keep their Spooner Street house in case they decide to move back. The cost of carrying both homes is more than they feel comfortable spending, so they decide to rent out the Spooner Street property while settling into the new coastal property.

Fast-forward two years…

Lois and Peter absolutely love living in their new home and can't imagine ever going back to Spooner Street. With their newfound confidence and clarity, they put the Spooner Street home on the market for sale.

Six months later, the home sells for $1 million. Even though Lois and Peter haven't lived in the home for the past two and half years – and even though they've been renting it out during that time – they still qualify for the $500,000 gain exclusion since they still owned and lived in the property (as their primary residence) for at least two out of the last five years!

As this example illustrates, selling a former principal residence within three years of converting it to a rental property (so that the two-out-of-the-last-five-years requirement is still met) allows the homeowners to retain the full capital gain exclusion.

From a tax planning standpoint, this makes it essential to begin conversations about a potential sale early enough to ensure that if there is a desire to sell, it happens before the three-year deadline.

Example: Now consider the same facts from the previous example, but this time Lois and Peter aren't ready to let go of their Spooner Street residence at the two-year mark. In fact, it's not until the three-year point that they finally feel ready to sell.

Fortunately for them, it's a seller's market. The property sells quickly – really quickly – with a cash buyer offering to close in one week for $25,000 over the $1 million ask price.

On the surface, Lois and Peter should be thrilled with the outcome. A cash buyer, quick sale, and over asking price!? Sounds like every seller's dream. Unfortunately, while the Spooner Street house may have sold quickly, it wasn't quick enough to help Lois and Peter save their $500,000 gain exclusion.

While the couple still meets the ownership requirement for the exclusion (they've owned the property for the past five years), they don't meet the use requirement. Since they've been out of the house for more than three years now, they've used the house as their primary residence for less than the required two out of the previous five years.

Accordingly, the entire gain on the sale of the Spooner Street property will be taxable.

If the same sale had occurred just a few weeks earlier, Lois and Peter would have been able to exclude $500,000 of gain, resulting in substantial tax savings.

These examples illustrate how important the three-year mark can be – and why conversations ahead of that time are critical.

Nerd Note:

Any portion of the gain that is attributable to depreciation taken while the home was a rental home will be Section 1250 gain and taxed at ordinary income tax rates, up to a maximum of 25%. It is not eligible for the gain exclusion.

Sell To A Wholly Owned S Corporation

In some cases, individuals may be able to sell their primary residence to a wholly owned S corporation – that is, an S corporation that the homeowners themselves have created and fully own – and still qualify to receive the same treatment as if the sale were made to another buyer. While there is some discussion amongst tax professionals as to the validity of this approach, many tax experts believe it can be a viable strategy when structured properly.

Such a sale can offer taxpayers a number of potential benefits. One of the most notable is that it may allow individuals to make use of the gain exclusion on the sale of a personal residence even when they continue to (indirectly, via the S corporation) own the property.

Example: Recall Lois and Peter from our earlier examples. This time, let's suppose that they are only about six months out from the three-year deadline to sell their former primary residence and receive the gain exclusion. They understand the potential tax savings that would come from a sale before that time, but they're not quite convinced that they are ready to part with their old home forever just yet.

Enter the sale to a wholly owned S corporation. In this case, Lois and Peter could create a new S corporation and sell their personal residence to it for fair value, likely in exchange for a note back from the S corporation. Such a note can be structured in any number of ways (e.g., longer, shorter, amortizing, balloon-style, etc.) as long as it represents fair market value. Whatever the terms are, though, they should be respected by the taxpayer as failing to abide by the terms could easily result in the IRS disregarding the sale as a "sham transaction".

If this sale occurs prior to the three-year mark (since moving out of the home), the sale should still qualify for the $500,000 gain exclusion. If there is profit in excess of $500,000, that amount would be taxable. But unless the couple never planned to sell the house (in which case there'd be a future step-up in basis), accelerating taxation on the 'excess' gain (i.e., the gain in excess of the available exclusion) in exchange for the gain exclusion is likely 'winning' move.

In addition to securing a gain exclusion that would otherwise be lost, selling a former primary residence to an S corporation has another benefit if the property is to be subsequently rented. More specifically, such a sale can reset the basis of the property for future depreciation purposes.

Example: Once again, recall Lois and Peter, who bought their house on Spooner Street years ago for $300,000, and which has a current value of $1 million. If the couple continues to own the home personally while renting it, their basis for depreciation purposes (ignoring any value to the land or improvements made to the home over the years for simplicity) would be $300,000. Since residential real estate is generally depreciated over a period of 27.5 years, that would give the couple an annual depreciation of $10,909.

Suppose, however, that prior to renting the property, the couple sells the home to a wholly owned S corporation for the $1 million fair market value. Now, the S corporation can depreciate the home based on its $1 million purchase price instead of the 'old' $300,000 cost basis. At 27.5 years, that equates to an annual depreciation deduction of $36,364 – more than three times the annual deduction that would have been available absent such a sale!

Notably, the above S corporation strategies are not considered particularly aggressive in general, but there is at least enough ambiguity or grayness to the benefits of such sales that clients should always be encouraged to seek further counsel from a qualified tax or legal professional prior to moving forward with such an approach.

Of course, like many (most?) potential tax strategies, there are potential trade-offs to consider. For instance, if the home is purchased by the S corporation via a note, in general, the interest paid by the S corporation to its related-party owners would be taxable to them personally as interest income (though under special rules, it would not be subject to the 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT)). And while that same interest expense would be deductible to the S corporation as a business expense, the income and the expense may not fully offset one another in the same calendar year. This is because potential losses of the S corporation may not be fully passed through and usable by the owners on their personal returns, due to one or more limitations – such as the limit on the ability to deduct passive activity losses against non-passive income (as discussed in greater detail below).

1031 Exchange Can Defer Taxation

Once a home has been converted to a rental property, the owner may be able to dispose of the property without triggering current taxation by using a 1031 exchange to swap it for another like-kind property. This may be appealing if the owners want to stay invested in rental real estate without making their now-former residence their primary rental real estate, instead swapping to another piece of real estate to rent out (without triggering capital gains on their original property).

The caveat, however, is that a primary residence cannot be exchanged for rental real estate. Only rental real estate can be 1031 exchanged to another rental property. Which means the property must be fully converted to a rental property (and away from being a primary residence) before it can be exchanged.

There is no statutorily required time that a property must be rented before it qualifies for a 1031 exchange. However, many tax professionals recommend holding the property as a rental for a minimum of 1–2 years to reduce the risk of an IRS challenge (e.g., the IRS claiming the property was still the client's primary residence at the time of sale).

While there are many situations in which a 1031 exchange of a formerly-primary-residence property may be useful, the most obvious may be the following:

- The taxpayer is no longer eligible for the gain exclusion. If a sale of a principal residence turned rental property is happening more than three years after conversion, the gain exclusion is no longer available because the use test is no longer met. In such situations, a 1031 exchange can avoid current taxation and may provide an outsized benefit. (By contrast, if the sale is still within the capital gains exclusion window, it may be faster and easier to simply sell the property, exclude most or all of the capital gains, and simply reinvest the proceeds directly.)

- The taxpayer has substantial gain beyond the available exclusion. While the $250,000/$500,000 maximum gain exclusion amounts are arguably generous, they may not cover the gain on higher-priced and/or long-held personal residences. This is a growing problem, as the exclusion amounts are not indexed for inflation, even though home prices (generally) continue to appreciate over time!

Suppose, for instance, an individual purchased a home for $1 million 20 years ago. Today, that home might be worth $3 million or even $4 million. And while excluding $500,000 of the gain on such a sale is better than nothing, it would still leave the overwhelming majority of the gain on such a sale subject to income taxes. However, if the home is first converted to a rental property instead, it can later be swapped for another like-kind property via a 1031 exchange, deferring taxation on the entire profit.

Notably, the merits of both approaches above are enhanced for an individual nearing the end of their life expectancy. Property received in a 1031 exchange can still be eligible for a step-up in basis, which can turn deferred capital gains into a permanently avoided tax liability for heirs.

Implementing An "1152 Plan"

First, a little transparency… there's no actual thing called an "1152 Plan". It's just a (perhaps silly) way of describing a strategy that combines the gain exclusion available for a primary residence (under Section 121) and the tax deferral provided by a 1031 exchange (121 + 1031 = 1152) in a single transaction.

While implementing an 1152 plan takes a fair amount of planning and forethought, for the right type of client, the benefits can be pretty astounding.

In short, an 1152 plan allows a client to exclude up to their applicable maximum gain exclusion amount, while also deferring any excess gains via a 1031 exchange. This is accomplished by splitting the proceeds of the sale – walking away with the portion that's sheltered by the Section 121 capital gains exclusion for selling the primary residence and using the rest of the proceeds to purchase a subsequent rental property in a manner that still qualifies for a 1031 exchange.

To be effective, though, there's a tight window of time in which the strategy must be deployed. Specifically, a former principal residence turned rental home must generally be sold within one to three years of being converted to a rental home in order for this approach to work.

Why?

Because, as discussed earlier, in order to qualify for the gain exclusion, the sale of a former principal residence turned rental home must, in most cases, be completed within three years of the change in status of the property. That deadline sets the upper limit on the timeframe in which this strategy can be executed.

At the same time, to satisfy the 1031 exchange requirements and avoid a potential challenge from the IRS, the same property must generally be held as a rental for at least a year (and some tax professionals recommend at least two). That sets the lower limit on the time frame for the strategy.

Put together, this means there's a fairly tight 1–2 year window during which an 1152 plan can be executed effectively to provide the right type of client a massive tax break.

Example: Mort lives in a home that he and his wife, Muriel, purchased in 1990 for $120,000. Over the years, the couple made additional improvements of $80,000, giving them a total adjusted basis of $200,000.

In recent years, the surrounding area has blossomed, and the home's value has increased to $1,100,000. Unfortunately, Muriel died in September of 2010, so Mort is only eligible for a maximum gain exclusion of $250,000 upon the sale of his residence. Selling the property now would result in a significant taxable gain.

At the same time, Mort is in declining health and doesn't expect to live longer than another 5 to 7 years. He'd like to move to Florida and buy a small condo, but he'd need the cash from the sale of his home to make the purchase. He also doesn't want to trigger a large capital gains tax – especially knowing that his heirs would receive a step-up in basis if he held onto the appreciated property until death.

Given this fact pattern, Mort would be an excellent candidate for exploring an 1152 plan.

To implement the plan, Mort could move to Florida and rent a place for a few years, while also renting out his old home. After two years, he could sell the rental home to unlock the 1152 plan benefits.

Assuming the former home turned rental sells for $1,100,000, Mort could 'pocket' $250,000 of cash from the sale under the gain exclusion and use that to buy his new condo.

The remaining $1,100,000 – $250,000 = $850,000 could then be reinvested into another rental property via a 1031 exchange. If Mort holds the new rental until death, his heirs would be eligible for a step-up in basis and could sell the property free of income tax.

Nerd Note:

In order for the 1152 plan to work, the 'excess' gain must be reinvested through a valid 1031 exchange. Thus, all the standard 1031 formalities and rules must be respected, including the use of a Qualified Intermediary to hold the proceeds of the sale until the 1031 exchange is completed, the identification of replacement property within 45 days of the home sale, and the purchase of replacement property within 180 days of the home sale.

Be Mindful Of Passive Activity Loss Rules

In many circumstances, particularly early on in a property's rental "life cycle", the rental activity can result in a loss. And in general, rental real estate is a passive activity, which means losses can only be used to offset other passive activities.

An exception to the passive activity loss rules is available, however, for individuals who are "active participants" in rental activities and have AGI below $100,000. In such situations, individuals can deduct up to $25,000 of passive losses from their real estate activities against non-passive income (e.g., interest, dividends, retirement account distributions).

Nerd Note:

"Active participation" is a fairly modest standard, especially compared to "material participation". It generally requires the individual to own at least 10% of the rental property and be substantially involved in its management (e.g., signing leases, authorizing repairs).

By contrast, material participation turns what would otherwise be a passive activity into an active one, removing the barrier of the passive activity loss rules in deducting losses of the business on the owner's personal return. Material participation is a much higher standard, though, and requires meeting one or more of seven material participation tests.

Notably, though, this exception to the regular passive activity loss limitations is phased out as a taxpayer's income goes from $100,000 to $150,000. Accordingly, advisors should give extra attention to potential income tax planning approaches that could either raise a client's income enough to phase them out of all or a portion of this deduction, or lower their income enough to receive some or all of it.

In effect, for every $2 of income a client adds between $100,000 and $150,000 of AGI, they may have to pay tax on an additional $3: $2 for the actual income, and $1 less of passive activity losses that can be used to offset non-passive income. By contrast, the opposite is also true: For every $2 of income a client reduces in that same range, they may reduce their taxable income by $3: $2 less of actual income, plus $1 of additional passive activity losses that can now offset non-passive income.

Remember, when it comes to tax planning, it's all about the marginal rate – not the bracket. So it's important to be especially mindful anytime adding or subtracting income can have an outsized impact on a client's marginal rate.

In most cases, when a homeowner is ready to leave their primary residence behind and head elsewhere, they're simply going to sell their home and either buy or rent a new residence. However, in certain circumstances – such as when the existing home may be able to generate significant rental income or when the owner wants to avoid incurring capital gains on a highly appreciated property – transitioning the 'old' primary residence to a rental property can make for an intriguing option.

Notably, the gain exclusion available under Section 121 can remain available for up to three years after the property is no longer the owner's primary residence, and can even be utilized in a sale to a wholly owned S corporation. Alternatively, once converted to a rental property, tax deferral can be maintained through a 1031 exchange – or variations thereof (e.g., "1152 plan").

Ultimately, the key point is that when changing primary residences, tax-sensitive clients often have more options than they realize – and which should be considered before any irreversible decisions are made.