Executive Summary

Advisors launching their own firms often wear every hat – from marketing to compliance to client service – and while solo practice offers flexibility, it also comes with inevitable limits on time and energy. Eventually, growing client demands push the advisor to a key decision point: remain solo or hire the firm's first employee? Historically, the "capacity crossroads" emerged around $250,000 to $400,000 in annual revenue, or 30–40 clients. This crossroads also implies a risk, as hiring too early can lead to financial strain, while hiring too late can result in burnout and a decline in service quality. For growth-minded advisors, the first hire is not a matter of "if", but a question of "when" – and advances in technology are rapidly shifting that timeline.

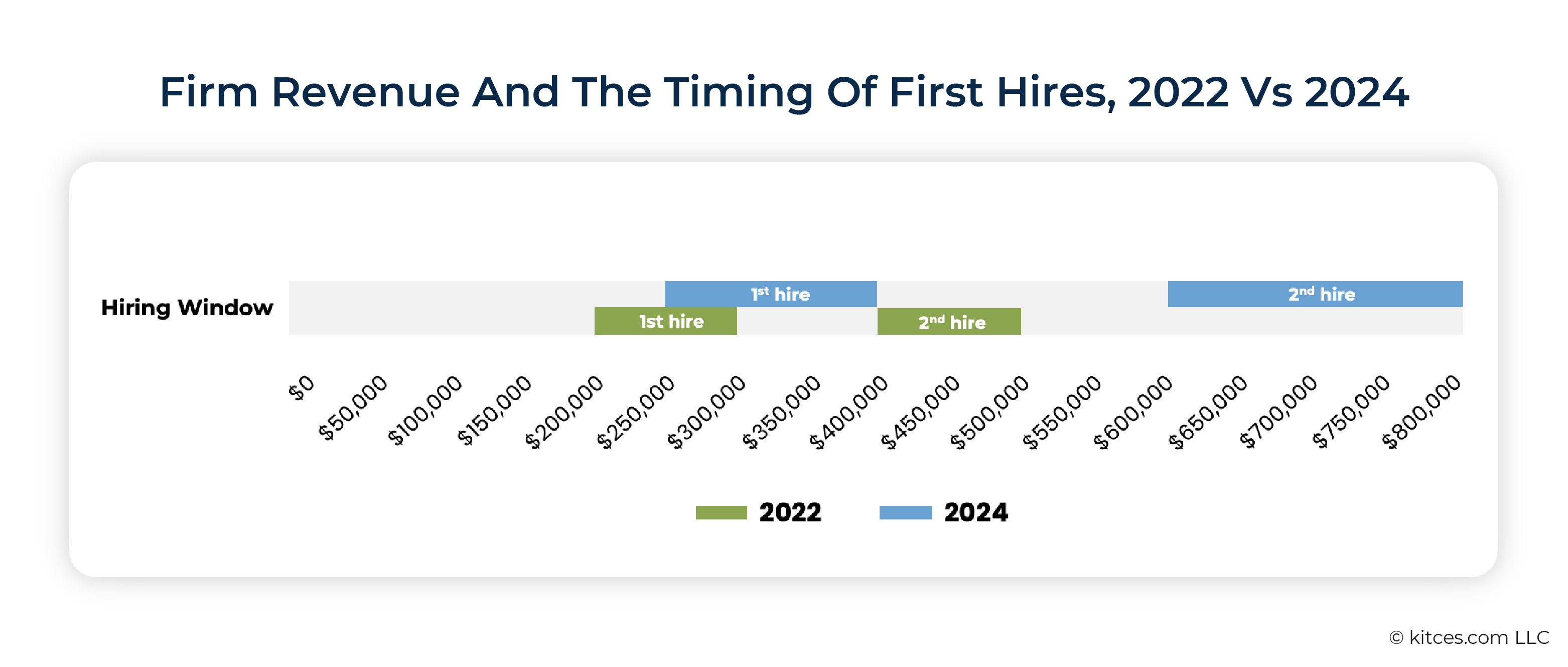

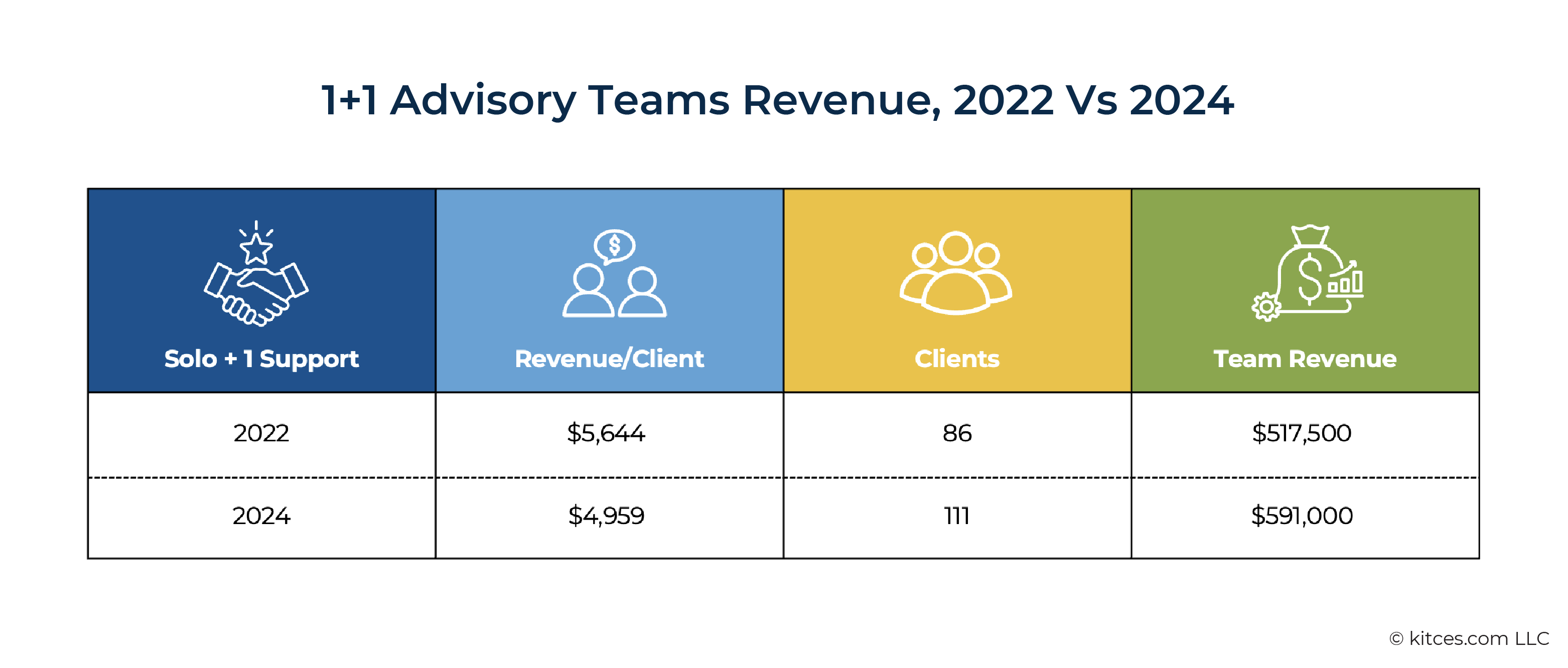

In this article, Sydney Squires, Senior Financial Planning Nerd, discusses how technology has shifted the 'new' capacity crossroads for advisors looking to make their first hires. Data from Kitces Research indicate that hiring patterns have undergone notable changes in just a few years. In 2022, most firms made their first hire at $200,000–$300,000 in revenue, and the second at $400,000–$500,000. By 2024, those thresholds had risen: the first hire now often occurs between $250,000–$400,000, and the second between $600,000–$800,000. More telling, however, is the dramatic increase in productivity between those milestones. In 2022, firms with one support hire serviced 86 clients and generated $517,500 in revenue; by 2024, comparable firms handled 111 clients and earned $591,000, despite lower revenue per client. This jump highlights how much more effective teams have become, particularly when leveraging automation and process improvements.

This evolution is tied closely to the nature of advisory firm work. While front-office tasks like client meetings are resistant to automation and retain fixed time demands, middle- and back-office tasks – such as scheduling, meeting prep, and follow-up – are increasingly streamlined through technology and delegation. Today's first hire spends far less time on these tasks than they would have even a few years ago, thanks to tools like AI-generated meeting notes, automated email summaries, and scheduling software. These time savings not only boost the productivity of support staff but also free up lead advisors to focus on high-value, revenue-generating client work.

The result is a compounding effect: advisors can push their capacity threshold further before needing to hire, and when they do bring on help, they can leverage that new employee far more effectively. This trend is expected to continue as AI and automation technology advance, though limitations remain. Most advisors still view technology as a way to enhance efficiency, not replace human interaction, particularly in client-facing roles. As such, growth-focused firms will still need to hire eventually, but technology-savvy advisors can delay that decision until their firms are on stronger financial footing, reducing risk and maximizing return on investment.

Ultimately, the capacity crossroads can be extended and shaped by the advisor's willingness and ability to optimize operations. Those who embrace technology and process improvement can extend their capacity and delay hiring, while others may benefit more by hiring operationally strong staff who can build those systems for them. Regardless of approach, the key is a mindset of continual refinement – because as firms grow more efficient, they also create space to offer more value, serve more clients, and scale more sustainably!

When an advisor opens their own firm, they are typically responsible for every role – from compliance to marketing, prospecting to business strategy, and account management to client relationships. In those early days, there are many demands on an advisor's time, but the advisor eventually molds their schedule in a way that best fits their work style while still ensuring that all the work gets done. At the same time, as the number of clients gradually increases, so too does the time required to service those clients, even accounting for the efficiencies of experience. This presents a serious constraint on the advisor's time – a moment referred to as the "capacity crossroads". At this point, when an advisor is nearly at (or just past) their maximum professional capacity for work, they must determine whether to stay solo or to hire their first employee. For some advisors, that decision in itself is difficult. However, for those who have dreamed of building a boutique or enterprise firm, this first hire is not a question of 'if', but 'when'.

And when to make the firm's first full-time hire is a legitimate question, as it represents a substantial investment on behalf of the firm. Hiring too early can create substantive cashflow risk for the firm, and the new hire may not have enough work to fill their time. Hiring too late risks the founding advisor's personal capacity being overrun, which could potentially result in a decreased quality of service or burnout. And even if the advisor manages to get the timing right, advisors must also hire a right-fit employee to whom the advisor can actually delegate work.

How Building An Advisory Team Impacts Firm Productivity

Out of the myriad choices that must be made while building an advisory team, a few components have stood out from Kitces Research on How Financial Planners Actually Do Financial Planning:

First, most advisors typically reach their capacity threshold at $250,000–$400,000 in annual revenue. This is typically 30–40 client households.

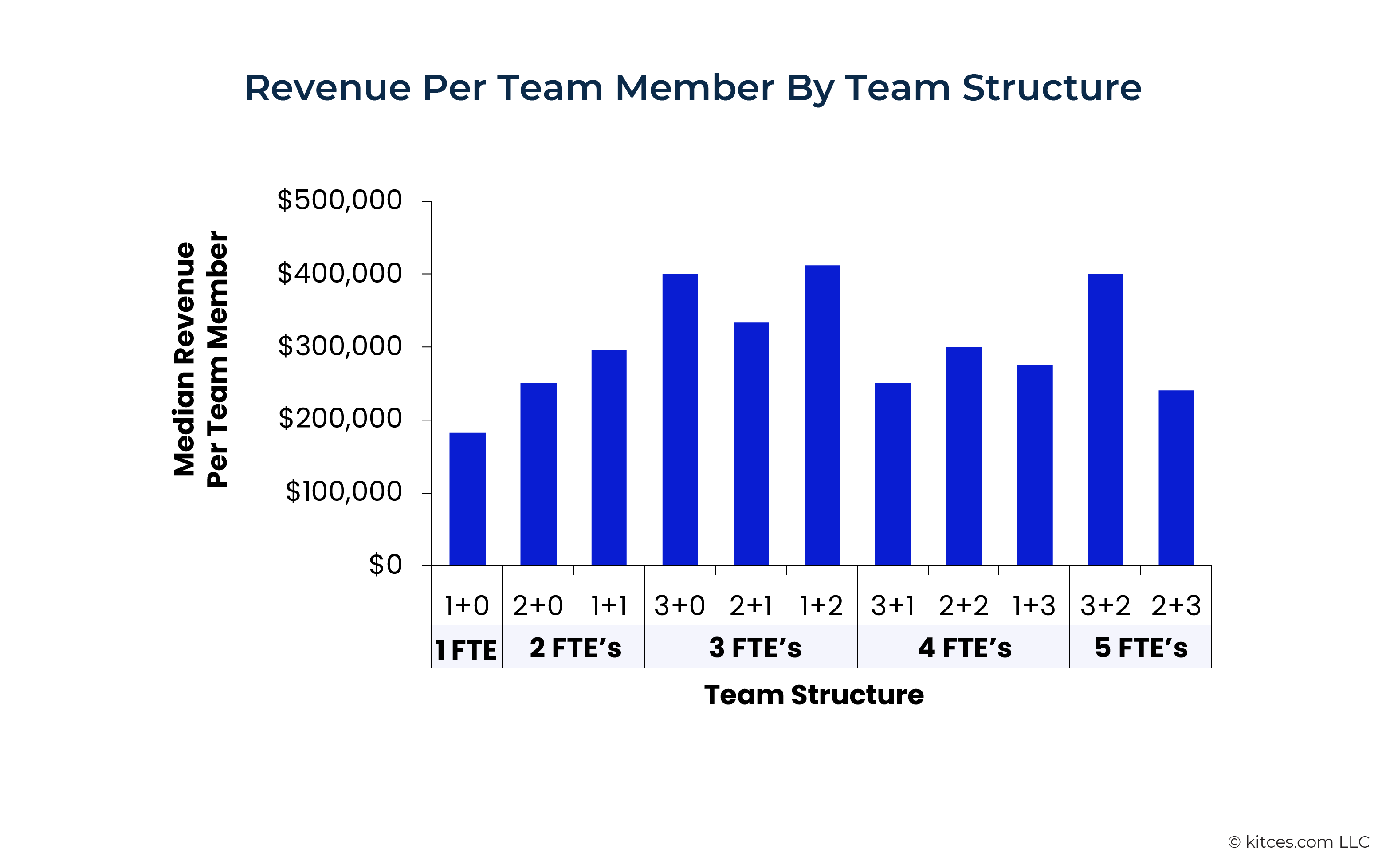

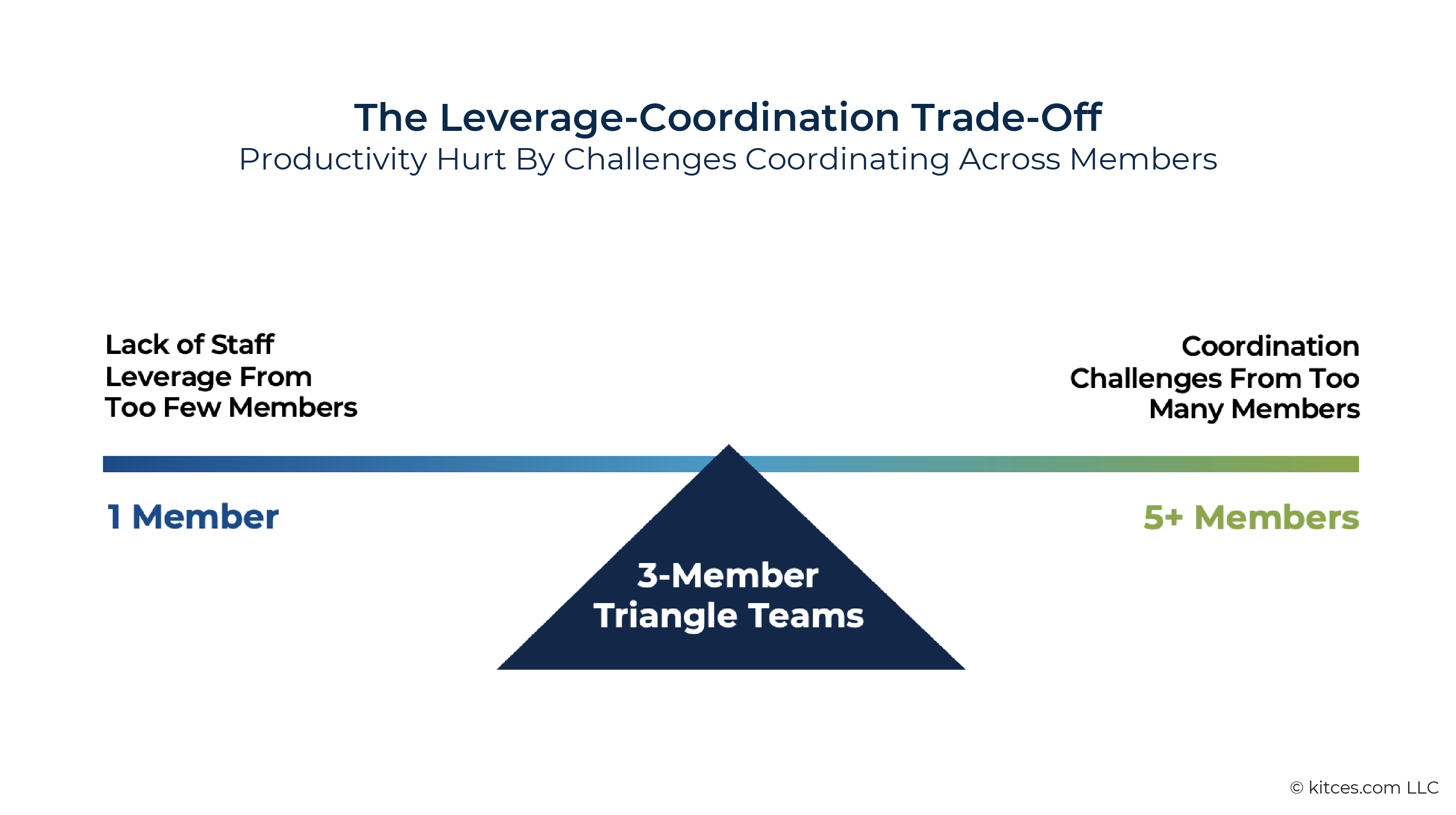

Second, firms usually see the greatest increase in productivity when they form a "Triangle Team" – that is, the lead advisor (e.g., the firm founder) hires a Client Service Associate (CSA) and an associate advisor. In the graphic below, Triangle Teams are shown as a 1+2 teams: one lead advisor and two support staff (the CSA and Associate Advisor), which creates some of the highest levels of productivity amongst any small advisory team.

The Triangle Team provides an outsized lift in productivity when compared to other team structures because the lead advisor is able to delegate the 'lower-value' tasks, which are important, but do not directly drive team revenue. This in turn enables the lead advisor to focus more of their time on revenue-producing activities such as prospecting and client meetings. At the same time, the management and meeting 'cost' is lower for a two-person team than a larger team – there are inherently fewer team-related pieces to keep organized!

In other words, Triangle Teams enable lead advisors to reap the benefits of delegation while minimizing the costs of team coordination and management.

How The Capacity Crossroads Is Changing

Constructing a triangle team remains a sound strategy for a hiring advisory firm. However, recent shifts in team productivity have started to alter the hiring timeline.

In the 2022 study on Kitces Productivity, advisory firms typically made their first hire at $200,000–$300,000 in revenue (with an average client load of 30–40 clients). The second employee was typically hired when the firm had reached $400,000–$500,000 in revenue.

When the same study was conducted in 2024, this hiring timeline had shifted dramatically: advisory firms typically made their first hire at $250,000–$400,000 in revenue. Which means that today, some advisory firms are making their first hire at almost the same revenue point that firms were making their second hire just a few years ago! And the median advisory firm made their second hire between $600,000–$800,000 in revenue.

Another way to look at this is in the difference in the number of clients supported by a "1+1" team over the last several years. In 2022, the average (established) solo advisor serviced 37 clients for a total revenue of $150,000; after they made their first hire, they serviced 86 clients for a total team revenue of $591,000.

In contrast, in 2024, the average advisor serviced 42 clients for team revenue, but after their first hire, they serviced a total of 111 clients – a 29% increase in client load, with a 14% increase in team revenue!

Even accounting for a decrease in average revenue per client, this represents a profound increase in team productivity over the last several years. Compared to just a few years ago, new hires are providing an outsized increase in the number of clients a firm can service. This in turn increases the firm's overall revenue and extends the timeline between its first and second hire. (And a higher bottom line also lowers the financial risk of hiring another full-time employee!)

In other words, something has changed in how that capacity is being managed.

Understanding Differences In Advisor Productivity

So, why has productivity increased among advisory firms? To understand this shift, it's helpful to start with the solo advisor's workload and then note how it changes when they make their first hire.

Solo advisors are typically responsible for almost everything at their firm as they build new processes, talk to prospects, and try to develop planning processes. At this stage, iteration is crucial – and most updates come as a result of continuously solving for the next immediate need – whether for a particular client or for the advisor themselves.

Sometimes, at a small business, the first iteration of a process is deemed 'good enough', and that initial solution more or less remains the procedure. However, if the work is done repeatedly and is somewhat painful (whether due to difficulty, time, or disinterest in the task itself), then the process is slowly improved over time. In practice, these process changes follow a cycle of expansion and reduction: they are first established, expanding to take up time that they initially did not. If the work is repeated enough, then it is eventually refined, which reduces (but rarely eliminates) the time required.

However, not all work shrinks equally. Advisory firm work can be divided into three components:

- Front-office: Client and prospect meetings (or other prospecting activities)

- Middle-office: Client meeting preparation, financial plan preparation, compliance, professional development, and investment research

- Back-office: Investment management, client servicing, and administrative work

Any of these areas of work can be improved upon. However, while process improvements can be made to the middle- and back-office tasks that reduce the time they take, it is perhaps more difficult to reduce the time required by front-office work.

For example, consider annual client meetings, which comprise front-, middle-, and back-office tasks. Imagine that one solo advisor's process is relatively simple: the meeting must be scheduled (back-office) and prepared for (middle-office), the meeting must happen (front-office), adjustments to the plan must be made (back-office), and follow-up communication must be sent (back-office). The middle- and back-office work lends itself more readily to automation and efficiency – for example, the advisor may set up a calendar management system that augments calendar scheduling and reminders. And the advisor may adjust their meeting schedule or experiment with different meeting lengths.

Yet after a certain point, every type of work hits an 'optimization wall' where it cannot be made more efficient while remaining effective. Front-office tasks hit this optimization wall much sooner than middle- and back-office tasks – at least, in terms of the time these tasks take. While a level of 'right-sizing' client communication can be helpful, the reality is that advisors cannot delegate away annual meetings to their support staff, nor can they conduct the meetings particularly faster.

The 'Double Lift' Of Delegation

While front-office tasks, such as prospecting and meeting with clients, resist time optimization, Kitces Research on Advisor Productivity also affirms that the more time that lead advisors spend on front-office tasks, the higher the firm's overall revenue. Which is logical, since the majority of front-office tasks are also revenue-producing. If the lead advisor is spending more time meeting with clients, serving more clients, and/or prospecting more, that in turn increases the firm's productivity. However, the majority of front-office tasks, again, cannot be done faster – so increasing revenue is tied to doing more of that client-facing work, not just doing it more efficiently.

On the other hand, middle- and back-office tasks are both easier to automate and to delegate to a new hire. When the lead advisor hires, they often begin to delegate middle- and back-office tasks. Returning to the annual meeting example, many of the tasks related to annual meetings can be delegated: calendar management, client meeting preparation, reviewing meeting notes, and even drafting the initial follow-up emails. Portions of these tasks can also be automated. For example, the calendar management software can automatically send clients a meeting reminder (with a link that allows the client to reschedule automatically in the event of a conflict), or the AI meeting notes software can queue up a first draft of an email summary.

This rise in automation has fundamentally shifted the responsibilities of the firm's first employee. While they may be responsible for the majority of middle- and back-office tasks, technology allows them to spend less time in the aggregate on this delegated work than was needed even a few years ago. This all adds up for the firm's first employee, who may be responsible for the majority of this work, but is spending less aggregate time on any particular task than they were even a few years ago. Compare, for example, the difference between an associate advisor documenting the client meeting notes, then drafting a summary email for the senior advisor to review, with the associate advisor fact-checking the AI meeting notes for accuracy, then reviewing the auto-generated summary email. The latter scenario will take far less time.

This increased efficiency is beneficial for one task, but becomes a force of nature when multiplied by the capabilities of automation and artificial intelligence across a variety of areas over the last few years, such as client meeting support and data gathering. This means that delegated tasks are taking less time, on average, than they were a few years ago. As a result, more work can be delegated – and the advisor can spend more time on revenue-producing tasks.

When this combination of time savings and delegation is multiplied by the way that advisor technology has advanced over the last few years, it is easy to see why firm productivity has expanded so greatly: the advisor is able to do more work, more efficiently, before they hire, and then their first employee is able to multiply this productivity boost.

How Technology (And Process) Optimization Changes The Capacity Crossroads

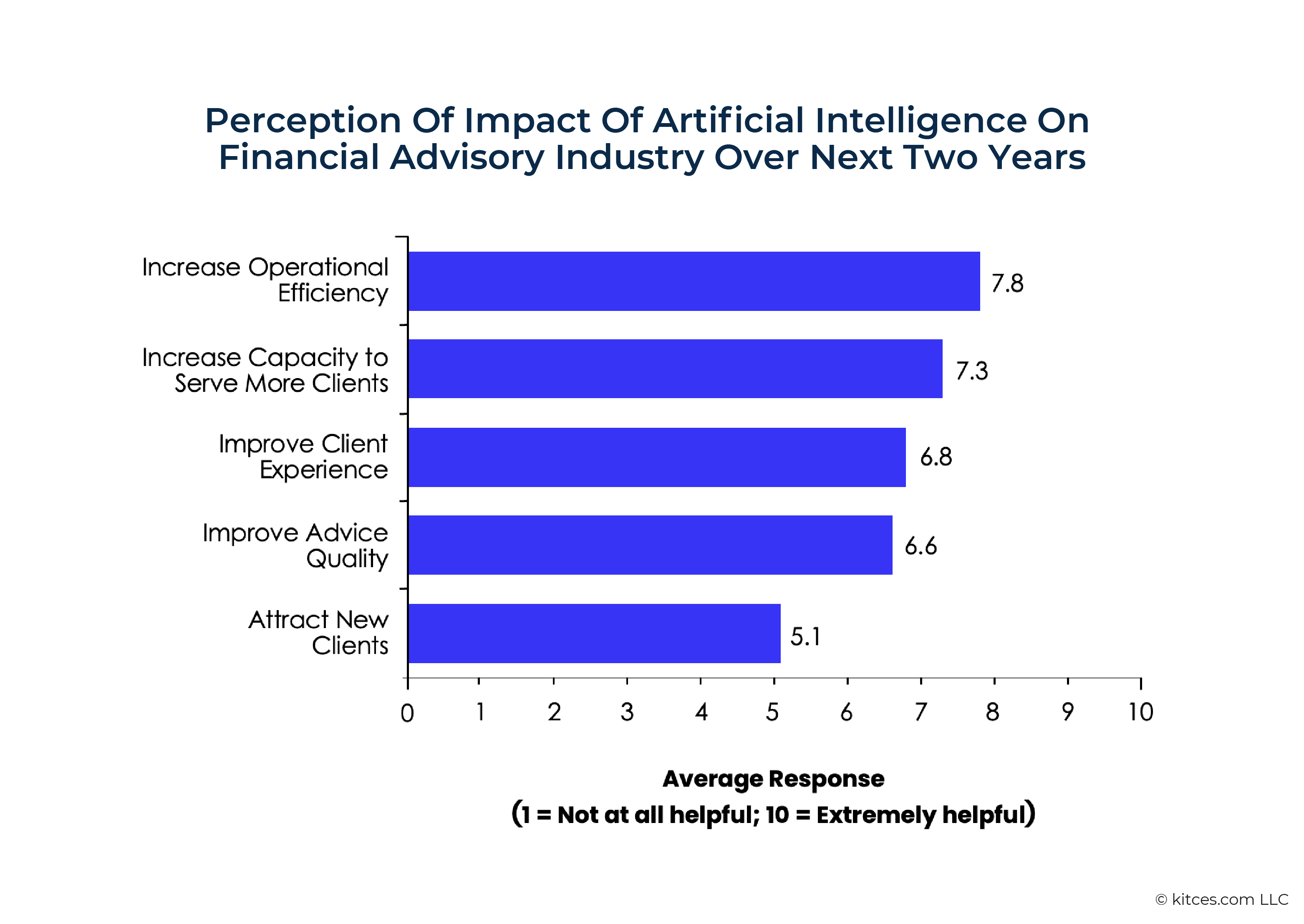

The potential for non-client-facing tasks to be optimized is also hinted at in Kitces Research on The Technology That Independent Financial Advisors Actually Use (And Like). When asked to rate how helpful advisors believe that AI will be across five business objectives over the next two years, most advisors envisioned that AI would be most helpful in increasing operational efficiency and increasing capacity to serve more clients. On the other hand, advisors were less optimistic about AI's capability to aid in attracting new clients.

Most advisors anticipate that AI (and automation at large) will be used as a time-saving force that makes work more efficient, rather than as a wholesale replacement for the work itself. As the report says: "Broadly, advisors are most interested in using AI to expedite tasks in ways that substantially reduce staff labor while still keeping the advisor 'in the loop' to review output and remain engaged in client-facing delivery".

In some ways, this pattern of middle- and back-office automation, delegation, and increases in efficiency is likely to continue – but the front-office client tasks are by nature difficult to automate and expedite in the same way (most clients who hire a human advisor aren't looking to have an annual review meeting with a robot).

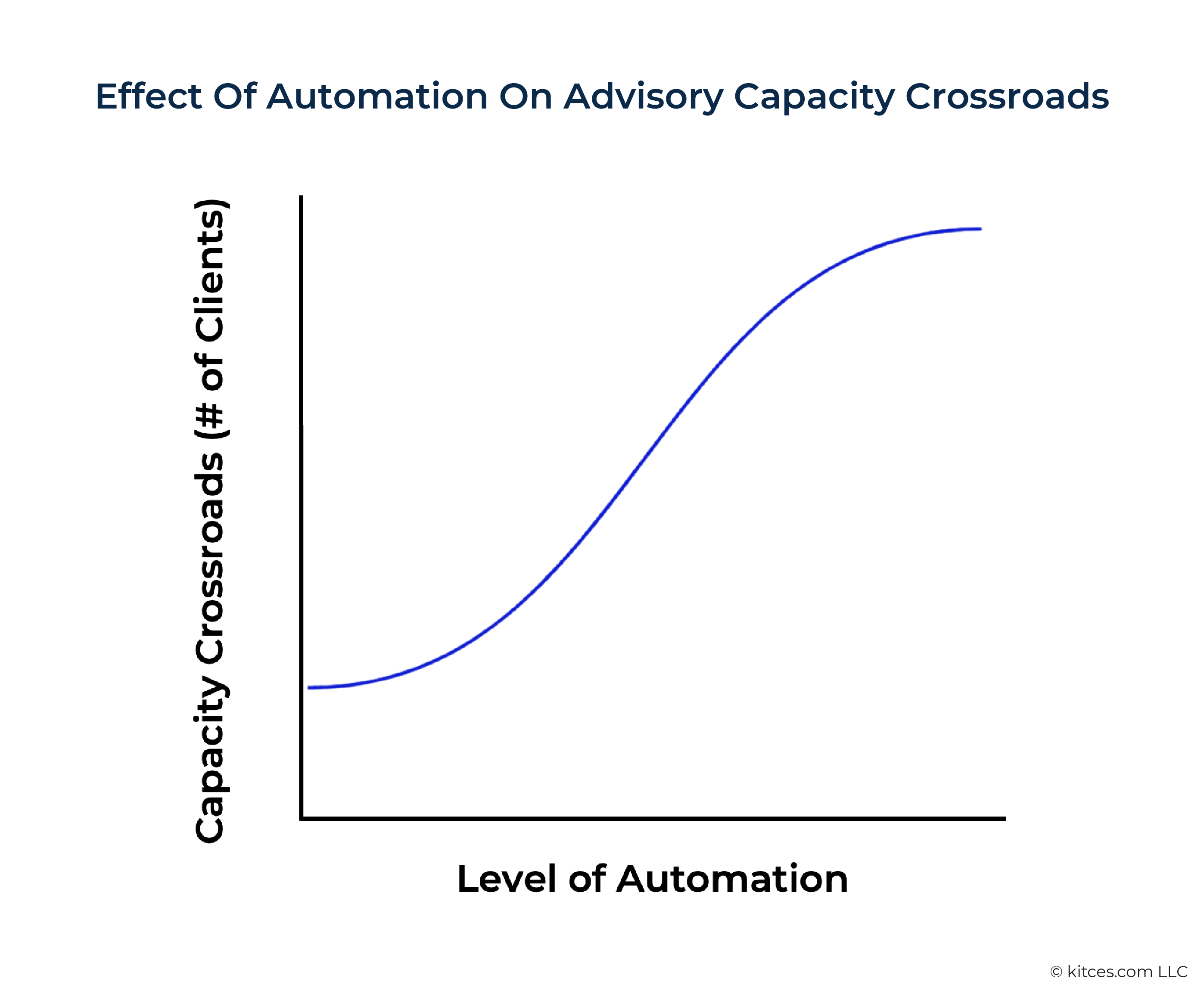

In other words, it is likely that the 'horizon' of the capacity crossroads will continue to shift – but this doesn't mean that the future of financial advice is a group of highly automated solo advisors. In fact, because many front-office tasks are resistant to compression and efficiency, growth-oriented advisors eventually will need to hire someone regardless of technology-driven efficiency gains. However, differences may begin to emerge between more process- and technology-oriented advisors and their less technologically inclined peers, with the former group hiring later than the latter group. This could pose an advantage for the advisor with technological savvy, who can delay hiring until the firm has higher revenue and is thus potentially more stable.

The question yet to be seen will be the pace of adoption. Even firms that are slow to adopt technological changes must do so at some pace to preserve the same level of competition with their peers. However, as the rate of technology development continues to accelerate, the differential early adopters and laggards will grow wider. At the same time, however, moving too quickly poses a different type of risk – of trying to grow too quickly in too many directions, or adopting technology solutions that don't solve a relevant problem for the firm.

Adopting Technology To Extend The Capacity Crossroads

As such, perhaps a logical conclusion for the advisor still looking to hire is to attempt to delay their capacity crossroads as far as possible by automating and improving their processes. Currently, technology integration and automation capabilities present endless possibilities. Most firms can yield meaningful improvements in automation without a deep knowledge of coding, programming, or software development. Most technologies offer automation options within the software itself (and integrations with other advisor technologies), which can yield great results when applied to common client problems.

In the event that two technologies don't integrate natively, software solutions such as Zapier or If This Then That may be able to increase the firm's automation capabilities. At this level of automation, the advisor creates "If / Then" statements with the help of their software, which can be adjusted based on certain conditions (This can be as simple as, "If a client call concludes, then the meeting notes are automatically sent to a certain email"). When identifying which tasks to automate, it's easiest to start with those that are unfulfilling and repetitive, yet unavoidable. Reducing the time spent on this type of work provides the advisor more time to focus on high-value work – or simply increases job satisfaction. For those without the technical inclination to fully automate tasks, even partial process improvements can reduce task time and yield positive results.

Implementing technology to streamline processes can be approached in a piecemeal way, especially given that most software has some level of automation capabilities that simply need to be activated and calibrated. Even taking an afternoon a month to improve one part of the process will yield significant results quickly.

When To Hire Anyway

For some advisors, iteratively improving their workflows, testing out technology solutions, and adjusting processes is both inherently rewarding and yields great results. However, there is an inherent upper limit to the results most advisors will get from automation, organization, and process optimization – especially when compared with the productivity boost that comes from hiring additional staff. This is perhaps most true for advisors who are not process- or automation-oriented – as refining processes will take more time, and the result may still be non-optimal.

For those advisors, it may yield greater results to explicitly screen for process-building and organizational inclinations in their hiring process – hiring someone with those strengths, who can help with building the processes as the firm grows, will pay better dividends in the long-term than whatever the non-process-oriented advisor would be able to build.

The trick is, to reap these benefits, the advisor must actually be willing to delegate responsibility to this person – not only for what is done, but also for how things are done. In that event, stay clear on which parts of a delivered item are crucial to the firm's brand, value to clients, or the advisor's preferences – and what is open to change. But insofar as that employee is able to own, simplify, and improve processes, then the advisor will be able to delegate more to them – which, again, lifts productivity in the long run!

Ultimately, as advisory firms iterate through technology and process solutions, much about the capacity crossroads stands to change, and it is likely that team productivity will continue to increase. The reality is, though, that as solutions simplify some processes, advisory firms always find new ways to add value and different offerings. Which, in turn, creates an environment where advisory firms continue to grow over time!

Leave a Reply