Executive Summary

Starting a new role as an associate advisor can be exciting – and nerve-racking. The onboarding period, which typically lasts between 90 days and six months, represents a critical window for associate advisors to demonstrate their value to the firm. There's a lot to learn in those early days, and even with a structured onboarding process, new advisors still carry much of the responsibility for absorbing procedures, taking initiative, and finding ways to contribute – often while they're still learning the ropes!

In this article, Senior Financial Planning Nerd Sydney Squires details how associate advisors can develop the required skills and make a strong impression during their onboarding period.

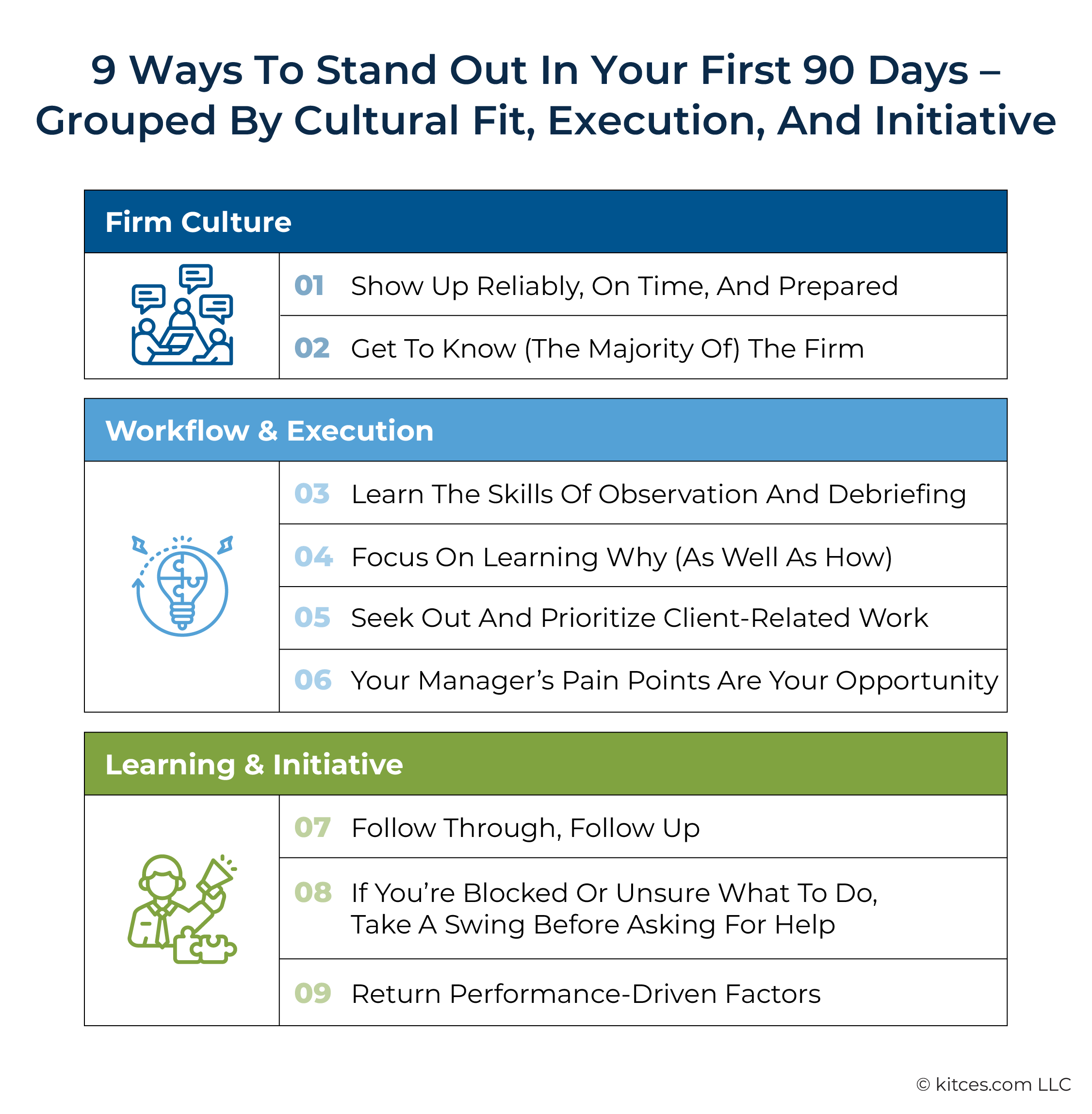

During onboarding, advisors are typically evaluated in two broad areas. The first is technical competence: the ability to learn the skills required for the role. This involves learning through shadowing and observation, following workflows and processes, and increasing responsibility with hands-on execution. The second is cultural fit. While more subjective, this part of the manager's evaluation is just as important – and often shaped by the associate advisor's communication style and interpersonal skills.

Thankfully, there are many strategies for associate advisors to set themselves up for success. For example, preparing for meetings by reviewing a client's background in advance, showing up on time, and proactively building relationships with colleagues, especially those in complementary roles, all go a long way in gaining context and building early trust within the advisory firm. Asking thoughtful questions to delve into client meeting strategies can help advisors transform their passive observation into a deeper understanding of the firm's client communication style. And since new advisors often bring fresh eyes to established systems, identifying inefficiencies and opportunities for improvement in processes can provide surprising value.

When roadblocks arise, proactively attempting to solve problems before asking for help is another subtle but powerful way to demonstrate initiative and learning. And when their managers are overwhelmed, offering to take on one of their smaller pain points can make a difference not only in helping the advisor learn but also in alleviating their manager's load – further demonstrating their value to the firm.

Ultimately, the key point is that mindset makes a tremendous difference during the onboarding period. Advisors who embrace curiosity, flexibility, and growth are more likely to find the transition more manageable – and more rewarding. The first 90 days are not about perfection but about steady, visible progress. And by focusing on showing up reliably, engaging thoughtfully, and easing their manager's load, new advisors can lay a strong foundation for long-term success!

After all the stress of finding a job, starting that job is often both relieving… but it can also introduce a whole new kind of stress. New hires have a fairly limited amount of time to show up well and make a great impression during their probationary training period (which is typically somewhere between 90 days and six months). Newly hired associate advisors have a lot to learn in a short period of time: who the clients are, who their teammates are, what the company culture is like, how to use the firm software… oh, and how to actually do their job!

What To Expect During The Onboarding Period

During the first 90 days, it's customary for the manager and new advisor to work closely together – starting with observation and gradually moving toward hands-on work with increasing independence. Associate advisors typically shadow client meetings, meet other employees, and take on entry-level tasks. By the end of the first 90 days, they're generally expected to be comfortably iterating on most of their day-to-day responsibilities, at which point they're formally evaluated by their manager.

Note: Managers are often senior advisors and may also be the owner or founder, especially in small firms. For clarity, this article will refer to the newly hired associate advisor as "the advisor", and their supervisor will be referred to as "the manager".

Broadly speaking, new advisors are evaluated in two main areas. The first is technical ability. In an associate or entry-level position, employees are evaluated for their immediate competence (i.e., can they perform the level of planning and technical work they conveyed during the interview process?) and their long-term aptitude. Since many roles begin with an extended period of observation, part of this evaluation also includes how effectively the advisor is learning from what they observe.

The second area of evaluation is cultural fit. This is more subjective in nature, but managers are often watching how the advisor's personality fits within the team dynamic. They may also be evaluating the associate advisor's long-term potential in future roles: Are they someone who might step into a management role? Take ownership of client relationships? Or develop into a deeply technical specialist? These aren't decisions that get made during the first 90 days, but it's common for managers to have these possibilities in mind as they assess how the advisor might fit into the long-term future of the firm.

In short, a lot depends on doing good work in the first 90 days.

Taking Initiative As A New Employee

The paradox of onboarding is that associate advisors are often trying to demonstrate that they're proactive, problem-solving self-starters… but they may not know how to do anything yet (at least within the framework of the firm). At the same time, managers are often under pressure to get the new advisor up to speed quickly enough to begin delegating some of the work, especially if the position was created to replace someone who left unexpectedly. The manager may already be stretched thin – they've made time to interview and hire, and now they need to onboard. In the meantime, it's likely the work has piled up.

The new advisor will take that work on… eventually. But, especially in smaller firms – where it's harder to reabsorb work during times of turnover or absence – there's often a limit to how quickly the advisor can be trained and delegated to. (This dynamic tends to be less intense in larger firms with more robust onboarding programs and full-time team members who can focus on providing hiring support, but it takes a while to reach that level of infrastructure!)

Which means it's natural for the new advisor to feel like they're joining the race at mile 20 of the hiring-and-replacement marathon – and anyone who has run a marathon knows that the last six miles are solely about survival!

(To be clear, this doesn't mean the advisor is doing anything wrong; it's simply the reality of how stretched many managers are, especially with the responsibility to construct and carry out the onboarding plan. Being aware of this dynamic can help set realistic expectations – and perhaps ease some unnecessary self-doubt!)

Even when the manager is under pressure and stressed for time, they're almost always looking for opportunities to train, delegate, and reward proactive behavior. The manager wants the advisor to learn and master their role as quickly as possible – and even the more complex parts will eventually be passed down.

There are real and practical things an associate advisor can do not only to make a great impression with their (possibly harried) manager, but also to truly excel in their first 90 days – both in terms of building cultural fit and demonstrating technical ability.

Firm Culture

A big part of a new advisor's success comes from how well they show up – both literally and figuratively. That means being reliable, professional, and prepared, and also beginning to form the relationships that make collaboration and communication easier over time. These habits can quickly build trust and help new advisors become a valued part of the team.

1. Show Up Reliably, On Time, And Prepared

A big part of making a good impression in the first 90 days is simply showing up reliably – on time, consistently, and with a professional presence. Being punctual is often an invisible asset that may not be noticed when done well… but being late tends to be extremely visible. (To paraphrase the old saying, if someone can't be trusted with the small things, they won't be trusted with the big things.) Of course, emergencies happen and exceptions will come up, but aim for consistency.

Timeliness is especially important for client meetings. If meetings are virtual, plan to be 'in the call' a few minutes early, especially for the first call of the day. Meeting software has a habit of updating at the least convenient times (is anyone not in a meeting at 11 AM on a Tuesday?!), so it helps to buffer for software issues. For in-person meetings, check with the manager about when to enter the room – but be ready to do so at least a few minutes in advance.

Dressing professionally is another way to signal that the advisor takes their role seriously. What counts as 'professional' will vary depending on the firm, and a dress code is often a part of firm culture. A good general rule for the first 90 days is to dress about 5% better than the norm. For example, if most of the team wears jeans, that doesn't mean showing up in a suit – but dark jeans and a sweater may be a safe, slightly more polished choice. (And be sure to check if the firm has a different expectation on client meeting days – many do!)

Finally, come to meetings prepared. For client meetings, review the notes in advance. Understand who the clients are, their savings and goals, their stage of life, what to-dos came out of the last meeting, and the themes and expected outcomes of the current meeting. Most managers won't ask new associate advisors to lead meetings right away or to contribute beyond introductions, and being prepared and informed about the client shows respect for the client and the process.

2. Get To Know (The Majority Of) The Firm

While learning the day-to-day tasks is essential, taking time to build social rapport can also make a big difference. Getting along with coworkers helps with problem-solving amicably, navigating firm dynamics, and, perhaps most importantly, making the workday more enjoyable (because it's nice to enjoy the company of the people we spend so much of our time with!).

In small firms, there may only be a few people to meet. In larger firms, there may be entire departments to navigate. If there are a lot of people to choose from, consider starting with:

- Someone in a similar role who's slightly more senior (e.g., someone who joined a year earlier). They're likely to have salient, timely insights and may be a helpful guide through the early stages of onboarding.

- Someone on a complementary team, such as a Client Service Associate (CSA) or someone from the investments team. Making their jobs easier will go a long way in building goodwill and credibility.

- Someone further removed from the advisor's direct work – maybe someone in marketing or operations – just to get a broader sense of how the firm runs.

The conversations don't have to be deep or time-consuming. A quick coffee chat is usually plenty to get things started. Ask about their role and personal background, and don't be shy about asking for advice on navigating the firm – most people appreciate being asked.

Nerd Note:

Getting to know people and being sociable can feel like an extrovert's game. Some people are inherently social, but ultimately, sociability within the workplace is a skill set that can be learned. Good references include "How to Know a Person" by David Brooks and many of Dr. Meghaan Lurtz's articles (such as this one on communication styles). Knowing how to connect with others – whether coworkers or clients – is a foundational skill in this profession!

Getting to know people and being sociable can feel like an extrovert's game. Some people are inherently social, but ultimately, sociability within the workplace is a skill set that can be learned. Good references include "How to Know a Person" by David Brooks and many of Dr. Meghaan Lurtz's articles (such as this one on communication styles). Knowing how to connect with others – whether coworkers or clients – is a foundational skill in this profession!

One added benefit of getting to know others within the firm is having more people to turn to when questions come up. While managers are usually happy to answer questions, it helps to have a few friendly faces to lean on for the small stuff!

Understanding And Executing Within The Firm's Workflows

Alongside cultural fit, advisors are also evaluated on their technical skills. Early on, much of the learning happens through observation – especially in client meetings – but the real growth comes from turning that observation into action. By asking thoughtful questions, looking for hands-on opportunities, and understanding how firm processes support client outcomes, new advisors can begin to build confidence and competence in their day-to-day work.

3. Learn The Skills Of Observation And Debriefing

A major part of the onboarding process for associate advisors is shadowing, especially in client meetings. Observation is crucial, but the most important insights that experienced advisors have often come from nuanced, complex decisions that aren't always visible in the moment (Think of the classic duck-on-a-pond metaphor: calm on the surface, but paddling like mad underneath).

It's hard to appreciate that effort solely by observation, which is why taking the time to debrief calls can be valuable. Debriefing doesn't have to be done after each individual meeting; it can be done at the end of the day, or as a batch review of the week's meetings and calls. Either way, debriefing is an essential part of turning observation into learning.

Here are a few debriefing questions to spark valuable conversations about client meetings:

- How did you know to ask….?

- I'm not quite sure how [A] connected with [B]. Can you tell me how you knew to explore that further?

Why ask: This question can help delve deeper into the advisor's reasoning and decision-making. For example, did a client say something that implied a deeper issue prompted a follow-up question? - Was there anything unique you did for this client? Why?

Why ask: Financial advice work is highly relational, and every client is different. This question helps reveal how the advisor uniquely adjusts their approach based on the client's personality, communication style, life stage, financial education level, risk tolerance, and other traits. - Was there anything specific you wanted me to take away from that meeting?

Why ask: This catch-all gives the manager space to highlight more specific takeaways that may have been missed and helps reinforce the most important lessons.

4. Focus On Learning Why (As Well As How)

New hires bring a unique superpower to the table: they see everything with fresh eyes. That means they're often the first to notice processes that more-established team members have stopped questioning. Some workflows are highly refined and optimized. But others were put together in a rush, simply built to function – like a "6 PM on a Friday and never circled back" sort of decision (guilty). And some are just 'good enough' based on time or resource constraints. Still other processes are intentionally built around the client experience, even if they're not the most efficient.

It's helpful to learn the differences between these types of processes. While systems that reflect the firm's core value proposition are worth mastering, others may represent opportunities for iteration and improvement.

Understanding the components that are a part of the firm's core values – what keeps clients coming back and what sets the firm apart – also helps advisors make better decisions in the long term. Even if they're not making strategy decisions now, they might be asked for input as the firm considers expanding, retracting, or adjusting its offerings to clients.

5. Seek Out And Prioritize Client-Related Work

While shadowing and observation are important early learning tools, it's difficult to learn through observation alone – ultimately, doing the work is required to learn and master it. However, closing the gap between observation, practice, and production can be challenging. And while it can be tempting to wait until everything feels 'ready', that often leads to the familiar trap of needing experience to get experience.

Instead, look for opportunities to engage directly with clients' financial plans and problems, even if the work isn't so glamorous. This might include entering data, taking client meeting notes, reviewing AI-generated summaries, or helping with client communication or compliance tasks. These small, tangible contributions go a long way toward deepening understanding and retaining real-life applications and strategies, building credibility – and value – with their team and manager.

At first, most work will require review and feedback. But those review cycles are where real learning and growth happen. Advisors may find it helpful to track patterns in their feedback and create customized 'double-check' checklists over time to minimize missteps and match their personal workflow.

In the short term, diving into tangible work as quickly as possible might lead to more early mistakes – but it also leads to faster learning and a smoother path to mastery!

6. Your Manager's Pain Points Are Your Opportunity

One of the quickest ways to get involved in client-facing work – and become indispensable to the manager – is to help solve the pain points that cause them stress. Every manager has something they don't enjoy doing, or simply don't have time to do well. And every advisor has the potential to take one of those tasks off their plate.

It doesn't have to be a big move; just look for small ways to offer help where it's needed. It can be as simple as saying, "Hey, I would be happy to give this a try. What would that look like?" or "If it would help, I can try to take that on. Can I watch you do it, then give it a shot?"

If the advisor is observing a process, it can help to ask whether the session can be recorded. Having a reference point to follow makes it easier to take ownership without needing repeated instruction and demonstrates initiative in a way that tends to get noticed.

(As a personal aside, I've done this many times in my own career, and it's one of the quickest ways to get promoted, especially in small firms where managers are often stretched thin. A little "How hard can it be?" attitude can go a long way… even if the task turns out to be harder than expected!)

Learning And Initiative

Beyond learning the ropes and getting to know the team, new advisors also have to figure out how to stay afloat in the day-to-day workflows of a new role. Once the basics of fitting in and doing the work are underway, the next challenge is building the inner habits that help everything stick. Advisors who stay curious, keep track of what they're learning, and show up with a steady mindset tend to grow faster – and feel more confident doing it!

7. Follow Through, Follow Up

One of the clearest signs of task mastery is when a manager can stop checking to see whether something was done – or whether it was done correctly. There are two levels to this: first, being trusted that the work is getting done on time, and second, being trusted that the work is being done correctly and doesn't require review.

Level 1: Trust that tasks are getting done on time. Reaching the first level is nearly always achievable early on. Advisors can build this trust by meeting deadlines consistently and communicating clearly about progress. It's also important to understand the layers of review and approval that may be required between task assignment and final delivery.

Level 2: Trust that tasks are done correctly – without review. This second level may require more time, but it's a strong indicator that the advisor has mastered the work. There are likely some recurring tasks that can be learned to this degree within the first 90 days. The ideal is to reach a point where the advisor can be handed a task and to follow up only when the task is complete. This demonstrates the advisor's reliability and ability to work independently.

Striving for both levels helps establish credibility and lightens the manager's mental load – both of which make it easier for the advisor to earn more trust and responsibility going forward.

8. If Blocked Or Unsure, Least Take A Swing Before Asking For Help

When learning something new, it's normal to get stuck or feel unsure. And especially when client-facing work is involved, it's important not to take unnecessary risks. It's okay – and may be necessary – to say "I don't know" when initially working on tasks independently. But even so, it helps to make a thoughtful attempt at solving the problem before asking for help.

Whether the issue is about finding a file, formatting a deliverable, or troubleshooting a financial planning analysis, taking a moment to investigate often leads to useful insights. Even when the right solution isn't clear, it's more productive to say, "I looked in [place] and tried [approach], and I think the answer is [X]. Can I confirm that with you before I send it off – is that right?" Or to say, "I checked [resource] and tried [step], but I'm still not sure. Can you talk me through this again?"

(Note that there is an upper limit to this – don't spend most of the workday trying to solve a task that should take only 15 minutes!)

Over time, developing this type of problem-solving skill becomes essential. Advisors who can resolve smaller issues on their own tend to need less oversight, and meetings with their manager can focus more on high-value strategic conversations!

9. Don't Underestimate The Power Of A Good Mindset

Curiosity and flexibility are crucial in the early days of a new job. The learning curve may feel uncomfortable, especially if this is the advisor's first job out of college or first position with an advisory firm. Early career years can be unpredictable, and it's hard to know exactly which skills will matter most or what kind of work will feel the most rewarding.

That's why it helps to keep an open mind and keep exploring new professional opportunities and challenges. Develop a habit of being consistently curious and learning how to learn. Dig into issues. Reflect on new ideas. Books like "Hidden Potential" by Adam Grant and "Grit" by Angela Duckworth offer helpful insights into growth and resilience, and there are plenty of podcasts and other books that cover similar themes in more bite-sized ways. Subscribing to a few that focus on delivering better financial advice can be a great way to keep learning on the go.

That's why it helps to keep an open mind and keep exploring new professional opportunities and challenges. Develop a habit of being consistently curious and learning how to learn. Dig into issues. Reflect on new ideas. Books like "Hidden Potential" by Adam Grant and "Grit" by Angela Duckworth offer helpful insights into growth and resilience, and there are plenty of podcasts and other books that cover similar themes in more bite-sized ways. Subscribing to a few that focus on delivering better financial advice can be a great way to keep learning on the go.

It also helps to explore content that speaks to the firm's niche. For example, if a firm serves only C-suite executives, find out what those clients are reading or listening to. This kind of research not only improves understanding of the target audience, it can also help advisors ask sharper, more relevant questions in meetings.

Finally, if the firm owner mentions a particular book (or books) that have shaped their thinking or business approach, consider reading that, too. These resources often hold great insight into how the firm operates and what it values.

Finally, if the firm owner mentions a particular book (or books) that have shaped their thinking or business approach, consider reading that, too. These resources often hold great insight into how the firm operates and what it values.

Above all, be patient – with others, and with yourself. There's a lot to do and a lot to learn, and mistakes will happen! The important thing is to continue learning. The goal isn't perfection, but progress. Keep showing up, take the work seriously (but maintain a sense of humor), keep trying, and don't forget to celebrate the small wins along the way!

Ultimately, the first 90 days can feel busy and chaotic – but they're also full of opportunities. By remaining curious, trying new things, being dependable, and looking for ways to ease their manager's load, new advisors can make a strong early impression. And over time, they may surprise themselves with how quickly they grow – developing the technical and relational skills needed to give great financial advice!

Further resources:

10 Tips For New Financial Planners To Maximize Career Progression

Leave a Reply