Executive Summary

For financial advisors bound by a fiduciary duty, acting in the client's best interest goes beyond avoiding conflicts of interest: it also requires a duty of care. This means prudently evaluating whether an investment is suitable and fully understanding what's being recommended. It follows that the more complex or opaque an investment is, the more due diligence work is required to have a "reasonable basis" to believe a recommendation is in the client's best interest. As alternative investments have become more accessible to retail investors – and more aggressively marketed to financial advisors – cutting through the marketing noise to evaluate each potential investment on its own merits has also become more difficult.

The SEC has made clear that fulfilling the duty of care requires a documented due diligence process. In a 2023 Staff Bulletin, the SEC outlined essential considerations for evaluating an investment's appropriateness, including its objectives, cost structure, risk profile, liquidity, tax implications, and portfolio role. However, there is no one cookie-cutter process; the level of scrutiny an advisor applies must scale with the investment's complexity. Publicly available research tools (e.g., Morningstar) may suffice for evaluating straightforward products like index ETFs. But as advisors move up the complexity curve to alternative investments like options strategies, hedge funds, or private equity, the due diligence bar rises dramatically. Advisors must go deeper, not only in understanding the mechanics of a product, but also in stress-testing assumptions, vetting management, and evaluating operational integrity.

Private fund investments, such as private equity and private credit, present unique challenges. Technology platforms like CAIS and iCapital have lowered barriers to entry, and fund managers are tapping new pools of capital, leaving advisors flooded with opportunities to access products that were traditionally exclusive to institutional and high-net-worth investors. However, there's a critical distinction between access and appropriateness. Unlike public markets, there's no index for private funds: each is actively managed, often opaque, and highly variable in performance. Picking the wrong fund could lock up client capital in a poorly managed or even fraudulent investment with limited recourse – up to and including total loss. Advisors must therefore assess not only whether private investments make sense at the category level (given their illiquidity and downside risk), but also whether individual managers have credible strategies, sound operations, and fee structures that don't unduly erode returns.

Effective due diligence on private funds therefore requires a multi-layered analysis. At the client level, advisors must evaluate risk tolerance, liquidity needs, and whether simpler public-market solutions could meet the same goals. At the manager level, advisors must evaluate investment strategy, operational controls, and costs. Additionally, going beyond a fund's marketing materials is necessary to verify its stated investment strategy and adherence to it, ensure third-party oversight exists for fund accounting and audits, and analyze its fees and costs (including its provisions around leverage, incentive hurdles, and 'catch-up' provisions). As illustrated in a 2014 SEC Risk Alert, useful due diligence practices include demanding position-level transparency, conducting background checks, and even vetoing investments based on operational red flags.

The key point is that most alternative assets were historically limited to institutional investors presumed to have the resources to evaluate complex and risky investments – and when advisors recommending alternatives, they assume that evaluative responsibility. Outsourcing parts of the due diligence process to third-party providers like outsourced CIOs can help, but the fiduciary responsibility remains with the advisor. Ultimately, due diligence – whether outsourced or internal – must be thorough enough to reasonably justify that a given investment is in the client's best interest, protecting clients from unsuitable or dangerous investments and reinforcing the advisor's role as a prudent steward through thoughtful, well-informed recommendations.

The "Due Care" Obligation Of Advisors' Fiduciary Duty

One of the core duties of Registered Investment Advisors (RIAs) is to act in their clients' best interest when providing personalized investment advice. The Investment Advisers Act of 1940, which covers advisors registered with the SEC, along with state securities laws and regulations that cover advisors at the state level, imposes this fiduciary standard on all firms compensated for giving advice on securities, while the SEC's Regulation Best Interest rule similarly requires broker-dealer representatives to act in their clients' best interest when making investment recommendations.

On one level, this means advisors have a duty of loyalty to their clients and can't make recommendations that benefit themselves more than the client, e.g., broker-dealer or insurance representatives recommending the product that will earn the biggest commission for themselves rather than the one that actually best meets the client's goals and needs. Conflicted compensation models have long been an area of focus for both regulators and advocates of the fiduciary standard, as the most glaring cases of advisors failing to act in their clients' best interests have often come as a result of advisors seeking to maximize their own fees or commissions at the expense of what's right for the client.

But regardless of the advisor's own incentives, they also owe a duty of care to their clients, meaning advisors need to act prudently and reasonably when make recommendations and investing on the client's behalf – in other words, advisors can't recklessly use or recommend investment products to clients that are unsuitable for the client's needs and/or that the advisor doesn't fully understand. Even in a hypothetical world where the advisor doesn't have any compensation-based conflicts of interest, they still owe it to their clients to understand the risk, expected performance, costs, liquidity, tax characteristics, and other key factors relevant to any investments they recommend. And while the duty of care doesn't usually get as much attention in the media as compensation-related conflicts of interest, it nonetheless plays just as big of a role in upholding advisors' fiduciary duty.

The SEC and state regulators have enforced the duty of care in cases like Frontier Wealth Management, LLC and Shane Sokolosky, and UBS Financial Services Inc. Both involved advisors recommending complex options-based strategies without fully understanding how the strategies would perform in all market conditions, leading the advisors to misrepresent how risky the investment strategies really were and resulting in steep losses for clients who had expected a relatively conservative, low-volatility investment. Arbitrators have also levied large awards to investors in cases where advisors negligently recommended products that were far riskier than what the client was prepared to take on, including a recent eye-popping $133 million award to clients of an advisor who put them in a volatile structured-note strategy without being adequately trained or supervised on the strategy.

Notably, the issue in the cases above was not that the investments were risky or lost value – all investing involves assuming some degree of risk, and the possibility of short-term loss is often a necessary tradeoff for achieving the long-term return necessary to meet an investor's goals. The problem instead was that the advisors failed to adequately assess and communicate to clients how risky the investments they recommended actually were – either because the advisors weren't trained or supervised on the products they were recommending (as in the Frontier Wealth Management case), or because they misunderstood how the products would work in reality (as in the UBS case).

When an advisor doesn't understand the risks of a particular investment, it's impossible for them to properly disclose that risk to the client. It's also impossible to determine whether or not the client needs (or could tolerate) the level of risk the investment represents in their portfolio. And if the amount or type of risk a particular investment adds to a client's portfolio can't be known, then it's impossible to make a reasonable case that that investment is truly in the client's best interest. Which is what makes the duty of care such a central element of advisors' overall fiduciary duty.

Due Diligence Defined

An advisor's duty of care is why it's important to have a process for performing due diligence on any investment products being recommended – or under consideration for being recommended – in client portfolios. In its 2023 Staff Bulletin on Standards of Conduct for Broker-Dealers and Investment Advisers Care Obligations, the SEC broadly defines this process as "developing a sufficient understanding of the potential risks, rewards, and costs of the investment or investment strategy to have a reasonable basis to believe that the recommendation or advice could be in a retail investor's best interest".

Conversely, as the Staff Bulletin notes, firms with no due diligence process "cannot have a reasonable basis to believe that their recommendation or advice aligns with a retail investor's investment profile in a way that satisfies their obligations to make a recommendation or provide advice that is in the specific investor's best interest". In other words, in the SEC's view, it's impossible for an advisor to fulfill their fiduciary responsibility without an adequate understanding of the investment products or strategies they're recommending.

The SEC also includes a list of factors in its Staff Bulletin that their staff believe are among the most important for advisors to consider about potential investments, including:

- The investment's objectives (e.g., income, principal protection, growth, or other goals);

- Costs (e.g., management fees, performance incentive fees, borrowing costs);

- Risks and key characteristics (e.g., liquidity, margin or capital-call terms, and early repayment risks);

- Expected performance, including how the investment would perform under varying market or economic conditions;

- Other features, such as tax characteristics or guaranteed payments; and

- How the investment fits within the context of the investor's entire portfolio (e.g., is it a core holding or a small component, and does it diversify or concentrate the portfolio's assets?).

Different Investments Need Different Due Diligence Processes

For some investment products, the factors above may be enough to develop a sufficient understanding of the product to determine whether it's in the client's best interest. However, as the SEC Staff Bulletin notes, the list is non-exhaustive – implying that for at least some investments, those factors alone might not make up an adequate due diligence process.

The key phrase, which is used multiple times in the SEC's Staff Bulletin, is "reasonable basis". Advisors don't necessarily need to know everything about every potential investment option, but they do need to know enough to reasonably determine whether a particular option is in the client's best interest. For relatively simple and transparent investments, that determination might not be difficult to make. But for more complex or opaque products, the learning curve could be much steeper and require a much more thorough fact-finding process before deciding whether to make a recommendation.

In short, different investments require different levels of due diligence. While some are relatively transparent about their structure, risks, and costs, others require a much deeper dive for an advisor to meet the 'reasonable basis' standard. Rather than having a single, standard due diligence process for every single investment, RIAs are better off tailoring due diligence practices to each product or strategy so they can reasonably determine whether each would be in their clients' best interest.

Case Study: Three Due Diligence Processes

Imagine there are three RIAs: A, B, and C. RIA A uses investment strategies based on model portfolios consisting solely of index ETFs. RIA B uses complex bespoke options-based strategies constructed in-house with its own trading team. RIA C, meanwhile, allocates a portion of client portfolios to hedge funds managed by third-party asset managers.

RIA A's due diligence process is likely the simplest of the three. ETFs publish their holdings and fee schedules publicly and can be traded any time market exchanges are open. For an index-tracking ETF, the fund's performance history can be easily compared to the index it purports to follow to see how well it tracks the benchmark. Almost all due diligence for an index ETF can be done using free, publicly available data from sites like Morningstar or Yahoo Finance.

RIA B's due diligence process for its options strategies is more involved. Options strategies often have unique risk characteristics that make their behavior hard to predict. A 'black swan event' or sudden change in market volatility can turn a strategy that may have historically produced steady, low-risk returns into something much more volatile. For each options strategy that RIA B creates, it will need to test many different market conditions – not only those seen in recent history or at selected periods of time, but also numerous hypothetical, historical, and seemingly unlikely scenarios – to understand how the strategy could behave, so the advisor and client can have a realistic discussion of the potential risks and rewards. The good news, however, is that because RIA B creates its options strategies in-house, it presumably has access to the data on the options contracts and trading strategies it uses, allowing for objective evaluation (even though that evaluation must go deeper than RIA A's evaluation of its index-ETF models).

RIA C has the hardest due diligence task of all. As with RIA B, the hedge funds RIA C uses may employ complex strategies that are difficult to model (and indeed may change strategies on a regular basis). But unlike RIA B, which implements its own strategies in-house, RIA C relies on third-party investment managers who may be unwilling to divulge meaningful details of their investment or trading strategies. RIA C may have little to rely on for due diligence purposes other than the hedge fund's marketing materials, which naturally present the fund in the best light. As a result, RIA C may need to do much more detective work than either RIA A (which has a trove of publicly available ETF data) or RIA B (which has access to in-house data ).

The key point isn't that any of the above investment strategies is inherently better than the others – although the transparency and generally lower cost of the index-ETF strategy might be preferable all else being equal, there are cases where the risk-return characteristics of an option or hedge fund strategy might be more appealing (particularly for some very high-net-worth clients prioritizing principal protection over additional growth) despite the greater complexity and cost. But the farther an investment goes along the spectrum of opacity and complexity, the more work is needed to fully understand the investment well enough to determine whether it's in the client's best interest to recommend.

Due Diligence Considerations For Alternative Investments

The New Wave Of Private Investment Funds

Alternative investments have been a hot topic in recent years. "Alternatives" can encompass a broad range of investment approaches – from derivative strategies to commodities to crypto to hedge funds – but in the last few years the biggest focus in alternatives in the RIA space has been on private equity and private credit. Advisors have fielded an increasing number of pitches for different products, owing largely to two factors. First, technology and creative product structuring have lowered many of the historical barriers to investing in private funds, whose multimillion-dollar investment minimums and decade-plus lockup periods traditionally restricted their use to institutional investors (e.g., endowments and pension funds) or ultra-high-net-worth investors. Enterprise wealth managers have introduced 'feeder funds' to pool capital from multiple individual investors who otherwise might not meet the investment minimums on their own. Likewise, alternatives exchanges like CAIS, iCapital, and Alternatives Investment Exchange (AIX) have used technology to streamline the processes of sourcing, subscribing to, and monitoring alternative investments for financial advisors, which previously required extensive back-office support to manage the pile of paper subscription documents, capital calls, and account statements for each private investment.

The second factor behind the recent influx of pitches for alternative investments has been the alternative industry's own goals for growth. Asset managers face high demand for investment: On the equity side, startup companies increasingly seek to remain private instead of going public to retain founder control and avoid the higher scrutiny of publicly traded companies; on the debt side, companies have sought more private financing as traditional banks de-risk balance sheets to comply with the stricter capital requirements of Dodd-Frank. But while demand for private investment has increased, the supply of investors who are both eligible to invest in private funds (most private funds require 'accredited investors' with a net worth of over $1 million excluding a primary residence, or an income over $200,000 individually or $300,000 jointly) and willing to tolerate the illiquidity and other risks of private investments has stayed relatively static in recent years. Which has led alternative asset managers to seek out investors outside their usual base of institutional and high-net-worth clients, resulting in partnerships with traditional asset managers such as Capital Group (partnering with KKR), Calamos (with Aksia), and even Vanguard (with Blackstone) to offer private funds to retail clients, distributed either directly or – more often – via financial advisors.

Additionally, two new regulatory developments may further increase private fund offerings to retail investors. First, in May 2025, the SEC dropped its informal rule requiring closed-end retail funds with more than 15% of assets in private equity to limit their availability to accredited investors only. And in August 2025, President Trump signed an executive order directing the Department of Labor to re-examine fiduciary guidance on alternative assets and clarify how plan administrators should evaluate including alternative assets in their plan offerings – in other words, to issue regulations that would clear the way for including alternative assets in employer retirement plans like 401(k)s.

The Importance Of Picking The 'Right' Private Fund

In their pitch to advisors, alternative asset managers frame the increased access to private funds as an exciting new opportunity, "unleashing" the previously restricted access to such funds and "democratizing" investment vehicles that had once been available only to the wealthiest investors. Managers highlight recent private-equity outperformance versus public markets, the supposed illiquidity premium (i.e., the additional return demanded by investors for long lockup periods for private investments – although it's debatable whether such a premium really exists), and the potential for diversification and better risk-adjusted returns (although that's also debatable, given concerns about "volatility laundering", i.e., the mirage of stable returns created by infrequent valuation compared to public markets).

Setting aside the debate over the pros and cons of the asset class as a whole, advisors exploring investment in private funds must confront the reality that individual private funds vary greatly in performance. There is no private-markets version of an index fund that can passively track the returns of the entire asset class; instead, the industry is comprised entirely of actively managed funds that either over- or under-perform the average – often by large margins in either direction. So for advisors implementing private funds in client portfolios, there's a great deal riding on picking the right funds, especially given liquidity restrictions that prevent investors from pulling out their capital amid signs of trouble. And, unlike diversified portfolios of public securities, the realistic chance that a client's investment could go all the way to zero.

The decision, therefore, is not only whether to add private funds to clients' portfolios, but also how to screen potential investments to ensure clients end up in the right funds with appropriate safeguards and risk controls – not in vehicles that could be zeroed out if their funds are mismanaged.

Shaping A Due Diligence Process For Private Investments

The heightened risk of investing in private funds, and the wide dispersion in results between the best and worst funds, lead to two takeaways for advisors. First, private funds are likely appropriate only for clients who can absorb the risk (in the worst-case scenario) of a 100% loss on their investment. And second, for advisors who do allocate their clients into private funds, there is significant value to provide by vetting and screening private fund managers that can do a good job of safeguarding clients' money.

These two takeaways shape the due diligence process for alternative assets like private funds. As discussed earlier, the aim of due diligence is for the advisor to learn enough about a particular investment to have a reasonable basis for believing whether the investment is in the client's best interest. For alternative investments, the process must encompass not only whether alternatives in general serve the client's best interest, but also whether a specific fund or manager meets that standard.

Client Considerations: Risk, Liquidity, Opportunity

The first consideration – whether alternatives as a category are a good idea for the client – depends largely on the client's circumstances. As mentioned above, the client needs to be in a position where they can afford to lose whatever amount is allocated to alternatives – because even with thorough due diligence, circumstances beyond the manager's control can still sink an investment.

The other big factor is the client's liquidity needs. Will the client be okay if their investment is locked up for one year, five years, or even ten years or more? A newer class of so-called semiliquid alternatives like interval funds may offer more frequent redemption opportunities, but those might still allow withdrawals no more than once per quarter or so and may have caps on the amounts that can be withdrawn. For most alternatives, the assumption should be that the client won't need the funds for a long time. Which merits special consideration for clients like retirees who require regular portfolio withdrawals: In that case, the alternatives portion of their portfolio might be limited to funds that the client doesn't expect to use during their lifetime, with more liquid traditional investments funding ongoing expenses.

After taking the client's risk and liquidity needs into consideration, the high-level question for the advisor is: Does the opportunity in private equity or credit justify the investment, given the risk and liquidity downsides? Could the client achieve the same investment goals – whether they're focused on growth, income, preservation of principal, or a combination thereof – just as easily using public-market investments instead?

The SEC's 2023 Staff Bulletin on Standards of Conduct emphasizes these considerations, stating: "When recommending, or providing advice about, complex or risky products, the staff believes firms should consider whether lower risk or less complex options can achieve the same investment objectives." Advisors are also encouraged to put their analysis in writing, as the Staff Bulletin goes on to state: "Firms that make recommendations of, or provide advice about, complex or risky products to retail investors should also consider documenting the process and reasoning behind the particular recommendation or advice, including consideration of less complex alternatives, and how it fits within the retail investor's broader goals or strategy."

The implication is that advisors can expect scrutiny during examinations from the SEC or state regulators regarding their rationale for using alternatives, with emphasis on whether they are truly necessary to meet clients' investment goals. Advisors recommending alternatives would subsequently need to assess and document their clients' investment goals, risk tolerance, and liquidity needs – and maintain any analysis that supports the conclusion that alternative investments better meet those needs than other options.

Manager Considerations: Strategy, Operations, Costs

At the manager level, the aim of the due diligence process is to decide whether a particular manager or fund is best suited to meet the client's investment goals. There are essentially three main prongs of the process:

- The manager's investment strategy (both the underlying investment thesis and the manager's adherence to their stated strategy in practice);

- The manager's operations (both of the fund itself and the overarching asset manager); and

- The costs (management fees, performance incentive fees, and any internal expenses such as borrowing and operational costs).

For specific due diligence practices addressing these areas, the SEC's 2014 Risk Alert "Investment Adviser Due Diligence Processes For Selecting Alternative Investments And Their Respective Managers" can be a useful guide. Published in 2014, when the use of alternative investments was picking up among institutional investors like pension and endowment funds, the Risk Alert summarizes the SEC's examination findings on how RIAs and investment consultants conduct due diligence around alternative investments. While it does not explicitly endorse any specific practices – since the adequacy of any due diligence process depends greatly on circumstances specific to each individual firm – the Risk Alert does highlight ways RIAs can overcome the challenges of doing due diligence on alternative-investment managers.

Investment Strategy

Nearly all alternative investments take an active approach to investment management, so each manager presumably has some type of investment thesis and strategy that they pursue to achieve their investment objectives. For example, a private equity fund may target companies meeting certain criteria for size or profitability, while a hedge fund might develop models using large amounts of quantitative data that it believes will achieve better risk-adjusted returns. The manager due diligence process starts with asking what goals the manager is pursuing and what strategy is being used to get there.

However, it's not enough to simply accept the manager's description of their investment strategy at face value. Not all private investments are what they claim: Some supposedly sophisticated investment strategies have turned out to be either uninformed, speculative stock-picking, and in the worst cases, criminal Ponzi schemes. Unlike publicly traded investments like mutual funds and ETFs, private investments have few disclosure requirements and therefore leaving advisors with few ways to verify that the manager is actually following the stated strategy. The problems with many of the worst investment strategies don't become apparent until it's too late for investors to do anything about it. A deeper level of due diligence is needed to ensure that the manager's investment strategy aligns with the client's goals not just in theory, but in practice as well.

Some practices that RIAs have used to evaluate and verify alternatives managers' investment strategies, as highlighted in the SEC's Risk Alert, include:

- Requesting regular, position-level information on fund holdings, both to achieve transparency in how the client's funds were being invested and to allow for more in-depth risk analysis of the fund in the context of the client's entire portfolio;

- Requesting that client accounts be managed as a Separately Managed Account (SMA) rather than as shares of a larger pooled fund to provide full transparency and better monitoring of the fund's ongoing investment management; and

- Performing quantitative tests comparing the fund manager's stated investment strategy with reported investment returns to detect potentially manipulated return data and verify how closely the manager adheres to their stated strategy.

Operations

How a fund is managed on a day-to-day basis can tell a powerful story about its viability as a long-term investment. Alternative asset managers range from huge firms like Blackstone, KKR, and Bridgewater to small shops with only a handful of staff, and operational approaches are almost as varied as the firms themselves. Regardless of the firm's size, issues can arise when an investment manager doesn't have appropriate operational processes and safeguards in place, from inaccurate valuation of fund assets to self-dealing transactions to outright theft of client funds. Part of the expanded due diligence process for alternative assets may therefore include operational due diligence, to ensure that a manager who receives client funds has appropriate procedures in place to prevent their misuse.

Areas of operational due diligence highlighted in the SEC's Risk Alert include:

- Requiring managers to use an independent third-party administrator for services like fund accounting, NAV calculation, and reconciliation, and requiring periodic transparency reports provided directly from the administrator;

- Verifying the fund's relationships with third-party service providers like independent auditors and administrators (and doing additional due diligence on those third parties if they aren't known to the advisor);

- Conducting background checks on the alternative-investment manager and its staff;

- Requesting the results of any SEC examinations;

- Conducting on-site interviews at the manager's offices to better understand the firm culture and personnel; and

- Reviewing the fund's audited financial statements to identify issues such as concerns with valuation or related-party transactions.

If an alternatives manager uses a third-party auditor or administrator that is inexperienced or unqualified for the required work – or if the manager has made repeated changes to its key service providers – it can be a red flag that the manager is obscuring something in its operations that a more qualified or longer-tenured administrator would catch. Additionally, if there isn't an adequate process for fair valuation of fund holdings, or if there's a lack of controls or segregation between investment and operations staff, the investment team may have outsized influence on how the fund is valued – and therefore on the fund's performance and fee calculations.

The SEC's Risk Alert notes that some RIAs give their internal operational-due-diligence staff veto power over investment allocation decisions – meaning that even if an alternative investment seems to be sound from an investment standpoint, it could still be rejected if there are overriding concerns about its operations.

Cost

Alternatives are generally costlier than traditional investments. Beyond just management fees, which themselves can exceed 2% per year, alternatives often include performance incentive fees (usually billed as a percentage of the fund's profits above a specific return hurdle), feeder-fund fees, borrowing costs if the fund uses leverage, and 'passthrough' fees for overhead and administrative costs paid by fund investors rather than being absorbed by the manager itself – all of which can add up to 10% or more per year.

These higher fees don't necessarily mean that alternatives should never be recommended by financial advisors. While cost is one factor that must be considered in evaluating an investment, it isn't the only one, and a higher-cost selection could hypothetically be in the client's best interest if it can do a better job of meeting the client's investment goals than other lower-cost options. But the higher the investment's fees compared to other reasonable alternatives, the higher the barrier they present to being in the client's best interest.

In addition to being generally higher than traditional investments, alternatives' cost structures also tend to be more complex, making it harder to know total cost without digging into how a particular fund charges.

For example, while some funds charge their management fees based only on the amount of invested capital, others charge as a percentage of committed capital (i.e., dollars that investors have promised to put into the fund but that haven't actually been invested yet). Because uninvested capital can't earn a return, funds that charge based on committed capital tend to have worse net-of-fee returns, particularly in their early years when their capital hasn't been invested yet.

Similarly, some funds that use leverage charge fees based on gross assets (including borrowed assets) while others charge on net assets (excluding borrowed assets).

Example 1: A private debt fund raises $1 million in capital from investors and uses 20% leverage, giving it $1 million × (1 + 0.2) = $1.2 million in gross assets.

If the fund charges a nominal 2% management fee based on gross assets, its fee is $1.2 million × 0.02 = $24,000, meaning the actual management fee paid by investors on their invested capital is $24,000 ÷ $1 million = 2.4%.

Not only can the fund's gross-assets fee base make the stated 2% management fee misleading (since investors are charged a higher amount on their invested capital), but it also means that the fund must earn a higher rate of return on its borrowed dollars than its management fee plus the cost of borrowing before the fund's leverage benefits investors.

Example 2: Imagine the fund in Example 1 above borrows $200,000 at a 6% interest rate. The fund must therefore earn a rate of return of at least 6% (the cost of borrowing) + 2% (the management fee) = 8% before the investors see any value from the borrowed funds!

Furthermore, although incentive fees in alternative investments theoretically ensure that managers are only paid additional fees if investors also benefit, Morningstar's The State of Semiliquid Funds report details how funds can design their fee structures so the fund manager earns additional fees with little additional benefit to the investor. For example, many funds have a 'hurdle' rate of return above which incentive fees apply, but use 'catch-up' provisions that allow the manager to take the incentive fee on the fund's entire return after the hurdle rate is reached – not just the portion above the hurdle.

Example 3: A private fund charges a 20% incentive fee once performance reaches a 5% hurdle.

In Year 1, the fund returns 4.5%, so the incentive fee isn't triggered.

In Year 2, the fund returns 5.5%, triggering the 20% incentive fee on the fund's entire return.

The net return for the investors in Year 2 is 5.5% × (1 – 0.2) = 4.4%, which is less than the net return in Year 1, despite the gross return being 1% higher!

Additionally, as the Morningstar report lays out, private debt funds can set their incentive hurdles to be lower than the yields on the debt they hold, effectively guaranteeing that they'll surpass the hurdle rate and earn the 'incentive' fee each year.

Understanding the cost of alternative investments, then, often requires advisors to read carefully into fund literature and/or subscription documents to determine exactly how the fund's fees and costs are structured.

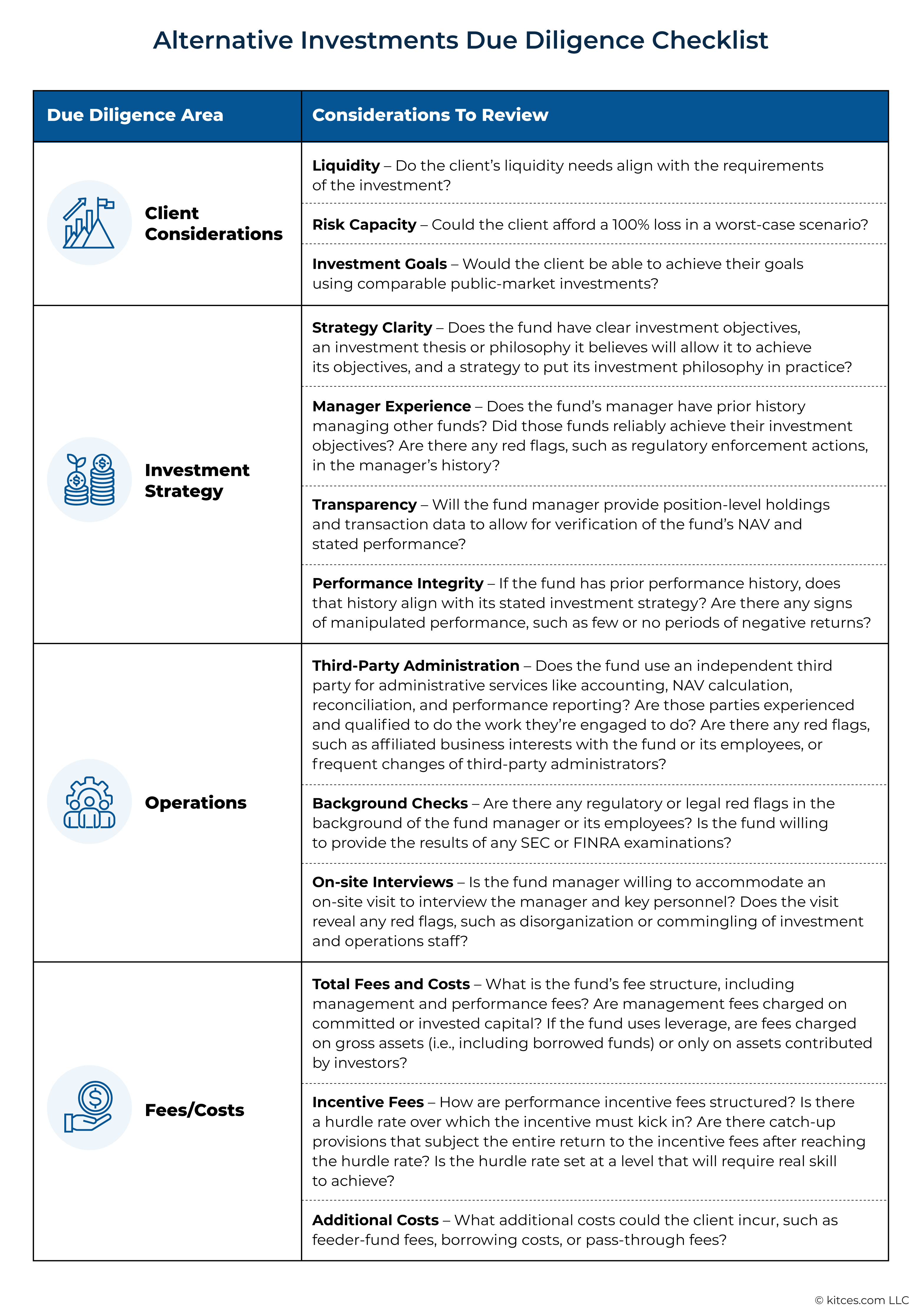

A Due Diligence Checklist For Alternative Investments

Distilling the considerations above to their key points, it's possible to create an advisor checklist that broadly covers the due diligence process for alternative investments. The checklist below begins with the appropriateness of the investment for the client, then moves to a detailed examination of the particular fund's investment strategy, operational structure, and fees and costs.

As noted earlier, regulators like the SEC expect advisory firms to tailor their due diligence processes to the specific investments under consideration, meaning that no single checklist will necessarily be the right process for every situation. For example, a hedge fund or option-based strategy may require additional quantitative analysis of the investment strategy – such as back-testing the strategy against different historical market environments – to adequately grasp the risks that a client would incur in investing in the strategy. But this checklist serves as a starting point for the kind of information an advisor would need to know about an alternative investment to reasonably determine whether alternative investment is truly in the client's best interest.

Due diligence on alternatives can take up a significant amount of firm resources, especially for RIAs without dedicated research staff. Advisors without in-house support can consider outsourcing some of the due diligence process – for example, Outsourced Chief Investment Officer (OCIO) services like Cornerstone Portfolio Research and Wealthspire Advisors can perform the due diligence work on private funds, and alternatives marketplace platforms like CAIS and iCapital perform some level of due diligence on funds listed on their exchanges – but ultimately it's up to the advisor to ensure that even if they're outsourcing their due diligence to a third party, the third party is covering (at least) all the areas of the above checklist, and any others that might be needed for the specific investment(s) the advisor is considering.

The bottom line is that, with alternatives increasingly promoted to financial advisors as a way to differentiate themselves by offering clients access to products once limited to institutional and ultra-high-net-worth investors, it's worth keeping in mind why those restraints existed in the first place. The complex blend of risk factors, illiquidity, and costs of alternative investments makes them better for those with the resources and expertise to vet investment options and make informed choices – and, by the same token, a poor fit for anyone drawn mainly by the mystique of an 'elite' investment vehicle. Advisors can play a key role, then, as a gatekeeper between their clients and the fund managers who want to distribute to them – using a thorough due diligence process to ensure client funds are allocated according to their best interest (even if that means not allocating to alternatives at all!).

Leave a Reply