Executive Summary

For many financial advisors, the journey of building a firm from scratch is a blend of idealism, grit, and inevitable growing pains. The early years in particular are fraught with challenges that make survival difficult. However, for those who persist, the reward can be a firm – and a team – that reflects the founder's values and supports their lifestyle.

In this article, Shawn Tydlaska, founder of Ballast Point Financial Planning, candidly shares the wins and lessons from his first nine years of entrepreneurship. He offers a grounded, honest account of building a multi-advisor firm from scratch – without a client base, personal brand, or local network – while navigating the complex realities of leadership, growth, starting a family, and self-worth. Now he leads a $130 million AUM firm serving over 130 households and reflects on both the strategic decisions that fueled his firm's growth and the missteps that tested his leadership and mental health along the way.

One of the most pivotal decisions was simply starting. Unable to find a salaried role aligned with his desire to serve younger clients, Shawn embraced an "accidental entrepreneur" path, launching his firm in 2016 after a marketing internship at Personal Capital. With modest personal overhead and strong intrinsic motivation, he minimized his overhead, meeting clients in coffee shops and libraries. And with few tech solutions designed for his clientele at the time, he built custom Excel templates for spending plans, equity compensation, and cash flow – tools that met the real-world planning needs of younger clients better than traditional retirement-centric software.

As the firm grew, so did the challenges of scaling a team. Shawn recounts the struggles of 'right-sizing' staffing to revenue, as well as the need for infrastructure to support people once they are hired. Career tracks, sabbatical policies, HR calendars, and feedback loops became essential to guiding the team and building a team culture – and so did learning how to transfer client relationships to developing advisors.

Alongside the professional journey came personal highs and lows: defining success on his own terms, adjusting to fatherhood, and working to balance health, family demands, and ambition in a shifting world. Through therapy, self-reflection, and personal growth, Shawn found greater clarity about what matters most to him.

Ultimately, the journey highlights the importance of aligning vision, values, and structure over time. Despite earlier ambitions focused on 'going big', his current definition of success emphasizes sustainability: building a firm that supports his team, nurtures his family, and creates space for meaningful work – without losing himself in the process. Looking ahead, part of his vision includes building on his work as co-founder of the BLX Internship Program, which provides internship opportunities for underrepresented groups in financial planning, and expands into creating infrastructure to address the broader industry challenges around accessibility and advisor development to offer opportunities to more aspiring planners!

As I reflect back on my first nine years in business, a lot has changed since I wrote my Last Kitces article in 2017 on the 12 Tips to Survive Your First 12 Months As An Independent Financial Advisor. My wife and I now have two kids, we bought a home, and are settling into life in the Bay Area. Professionally, my business and vision for the future have evolved beyond those early days. So now, nine years in, I thought it would be a good time to reflect on my journey, share the wins, be real about my mistakes (a.k.a. learnings), and talk about my plans for the future. I hope this article will be helpful to other advisors wherever they are on their journey.

Today, I would describe my firm, Ballast Point, as a "Small Giant" firm. We are an ensemble-based, multi-advisor financial planning, investment management, and tax preparation firm. We work with 136 ongoing households, and I have a team of five professionals (plus me). We also just brought on a summer intern through the BLX Internship Program, which I co-founded in 2020 to expand opportunities for aspiring Black and Latinx financial planners. The firm recently registered with the SEC and has about $130 million in AUM. However, our fees are based on client net worth rather than AUM, with an average upfront fee of $1,625 and an average ongoing fee of $653/month, for a run rate of about $1.065 million of financial planning revenue. Our tax prep services add about another $200k of ongoing revenue.

Historically, we bundled financial planning, investment management, and tax prep into one flat fee. Starting with the 2024 tax season, though, we decided to charge separately for tax prep. To support that shift, we hired a CPA/CFP to handle tax preparation completely in-house. Our average tax prep fee is about $2,000, and this year we expect to complete about 99 returns.

The team today is structured as follows: I am the CEO and lead advisor for 32 clients. Drew Hanessian, CFP, MBA, is a Lead Planner working with 55 clients. Vidalia Cornwall, CFP, is an Associate Advisor serving 53 clients. JoAnn Huber, CPA, PFS, CFP, is a Senior Tax Associate; she primarily handles tax preparation, creates tax projections, and addresses complex tax questions. She is still relatively new, so we're still figuring out how best to leverage her skills outside of tax season. Nikki, our part-time Operations Associate, keeps things running smoothly behind the scenes. And Kimberly Keesler Herrera, MBA, is our Financial Planning Resident, who is approaching her 90-day check-in and is planning to sit for the CFP exam in November.

1. Taking A Chance On Myself (Something I Got Right)

Before launching Ballast Point, I struggled to find my place in the industry. I think this is a common story: many of us enter financial planning because we want to help people, but landing that first job is incredibly difficult. According to a recent Cerulli study, 72% of advisors leave the industry during their first year – which doesn't surprise me. Most entry-level positions require new planners to achieve aggressive sales requirements despite having very limited experience. If they don't make it, the firm doesn't lose out; the clients they brought in simply stay behind as clients of the firm.

And for the positions that offer salaries, it often means working for more established firms with an older client base. I'm generalizing, but the typical client many firms target has $2–$10 million of AUM, is between 55 and 65 years old, and prefers to delegate.

But this wasn't the audience I wanted to serve. I think many of us got into the business to help others who are like them. I come from a middle-class family where we didn't talk about personal finance. I didn't know anything about how money worked. Once I learned how to best manage my own finances, I was hooked. I wanted to work with others who were young in their careers and who wanted to take control over their finances. Then, after working for a firm with a $2 million minimum, I decided to go to business school because I wanted to provide a wider audience with access to financial planning.

However, even after finishing business school – at age 34, with a CFP, an MBA, and a few years of planning experience under my belt – I struggled to find a job serving the demographic I wanted to work with. In 2015, I moved to the Bay Area without a job, hoping to land a position in the then-emerging field of FinTech (which was far smaller than the Kitces.com Financial AdvisorTech Solutions map today). At the time, I was looking for opportunities at firms that blended technology with personal advice. When those opportunities didn't pan out, I broadened my search and interviewed with upstart firms like Betterment, Wealthfront, NerdWallet, Credit Karma, and Personal Capital.

Since I was new to the Bay Area, I leaned on professional organizations like FPA San Francisco and FPA Silicon Valley to build connections, and eventually became a member at large for FPA San Francisco. Some of those early relationships were invaluable, and I even found informal mentors who helped guide me in those early years.

Eventually, I landed a job at Personal Capital as a post-MBA intern in their marketing department in the fall of 2015. It was during that time that I discovered XYPN and started to consider launching my own firm. The internship was supposed to last three months, extended to four, but it was clear there wouldn't be a long-term opportunity for me. So, on Valentine's Day of 2016, I joined XYPN and began exploring the idea of starting my firm.

At the time, my wife had a solid job at Thermo Fisher, we were renting an apartment that was relatively affordable (by Bay Area standards), and we didn't yet have kids or even our dog. I was hungry to pour myself into something and prove I could make it work. And to some extent, maybe I was trying to prove to myself that I belonged in this industry.

Looking back, I'd call myself an 'accidental entrepreneur'. And now, nine years later, I can't imagine working for someone else. The ideas I have for new businesses are never-ending and just keep coming; there is so much I want to do, and I have so much creativity inside of me. While I wouldn't mind partnering with someone on a new business venture, working the traditional 9–5 in corporate America is not my jam.

Takeaway:

When I reflect on those early years, it was both a safe and scary time to take a chance on myself, and I am very proud of making it work. I had no client base, had never been a lead planner, and was new to the Bay Area with no natural market to draw from – but I still built a firm from scratch.

For anyone thinking about starting a firm, I would recommend working at an RIA for two to three years, earning your CFP marks, and giving yourself three years of personal financial runway.

2. I Bootstrapped Everything! (Something I Got Right)

Early on, I had more time than client work. I also didn't have much revenue. So I had to get really creative about keeping my costs minimal.

One example: I didn't have a physical office. Instead, I figured out flexible ways to meet with prospects and clients. Back then, in pre-COVID times, even though I was set up to be a hybrid firm, most people still preferred meeting in person. So I found spaces that were mutually convenient for both sides: study rooms at my local library, local coffee shops, clients' homes, their company's meeting rooms, or even the lobby of a nearby hotel.

Initially, I worried that prospective clients would be wary of working with an advisor without an office. But one prospective client surprised me on the way out of our Discovery Meeting, remarking, "Maybe we want to work with an advisor who can figure out how to have office space without paying for it."

Takeaway:

As I reflect on this profession, I think financial advisors could almost be classified as professional communicators. So much of our work comes down to how we frame and present things to clients. Keeping overhead low without a physical office space, for example, can be framed as keeping costs low so client fees can stay low. The same principle can be applied to everything we do as planners:

- When a mistake happens, own up to it, explain what happened, and tell them how you will avoid it in the future.

- When raising fees, frame it around the improved services clients will receive and the added value they'll get from it.

3. Building A Vision For What I Wanted To Create (Something I Got Right)

When I launched back in 2016, there weren't templates for how to do financial planning for young professionals. It was really fun to create things from scratch, test them with clients, iterate, and polish them over time.

Instead of relying on complicated financial planning software tools, we built easy-to-understand Excel templates for things like spending plans, cash flow projections, beneficiary summaries, equity compensation projections, and housing affordability calculators. Most of the planning software back then – and even now – is geared toward retirement projections, but that wasn't the primary need for my clients.

In my first year, I often wondered if what I was doing was good enough. Classic impostor syndrome. To shorten my learning curve, I invested in sales and financial life planning training, which gave me EQ and sales process skills that have proven invaluable over the years. To gain perspective and see what others were doing in the industry, I hired my own planner, attended industry conferences and seminars, read blog posts, and tried out financial planning services like LearnVest, Facet, and Vanguard. I picked my peer's brains through 'financial planning swaps' where I provided a financial plan to them, and they provided one to me. (Sorry to my wife for making you work with so many planners over the years!)

I also collaborated with my launchers study group from XYPN. It was really helpful to share my early financial plans and get feedback on my work. My first engagement was a rent-versus-sell analysis for a client in San Diego. My study group peer, Eric Gabor, reviewed it and gave me confidence that my work was high-quality and worth way more than the $400 I charged.

Not only is it fun coming up with new tools, but I also had a vision for how I would want planning to be done if I were the client. That vision shaped the processes we use today – from creating a balance sheet before each meeting and tracking clients' net worth progress over time, to building quick calculators that show if they're on track for retirement.

Takeaway:

Having a clear vision for how to serve clients – and then manifesting it into reality – has been one of the most rewarding parts of building my firm. Don't be afraid to create tools that reflect your vision, and don't hesitate to get peer feedback along the way.

4. Treating My Financial Planning Firm Like A Business (Something I Got Right)

From day one, I had a business plan. It's really morphed since then – but that isn't the point. The point is to be intentional, thoughtful, and metric-driven. Early on, that meant tracking activity rather than results (something I talked a lot about in this podcast episode).

When I started my business, I held quarterly off-site retreats by myself to carve out time to 'work on the business'. While it's been difficult to continue holding retreats since I had my first child, I would really like to bring them back.

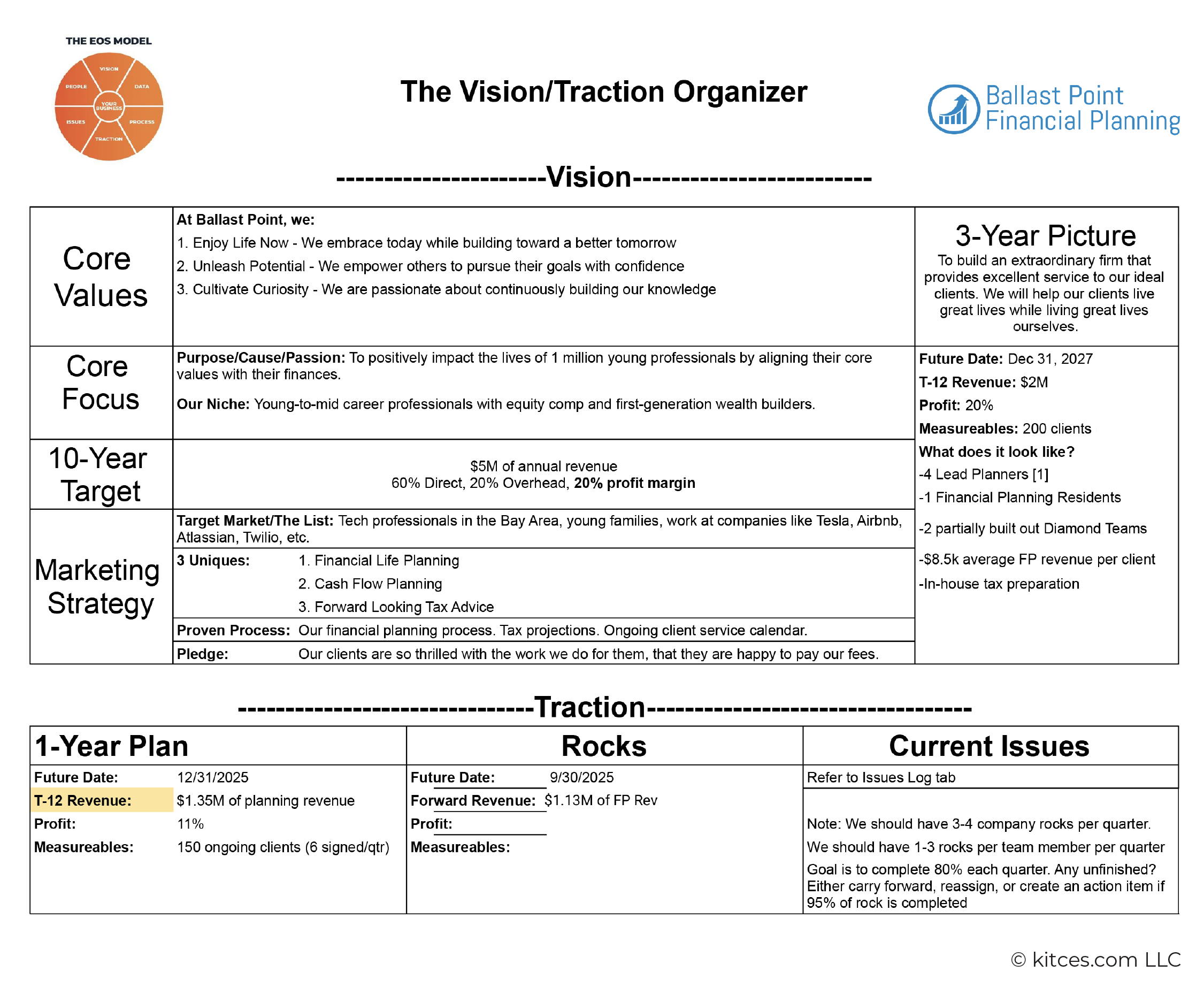

In my last blog post, I mentioned that I had just started to read Traction by Gino Wickman. That framework is still something we use today. Here is an example of our recent Vision/Traction Organizer (VTO).

There's something really valuable about stepping away from the day-to-day work and environment to think about what you want out of your business and your life. I encourage anyone to do this at an off-site location. Twice a year, I also get together with my team for business planning, team building, and relationship building.

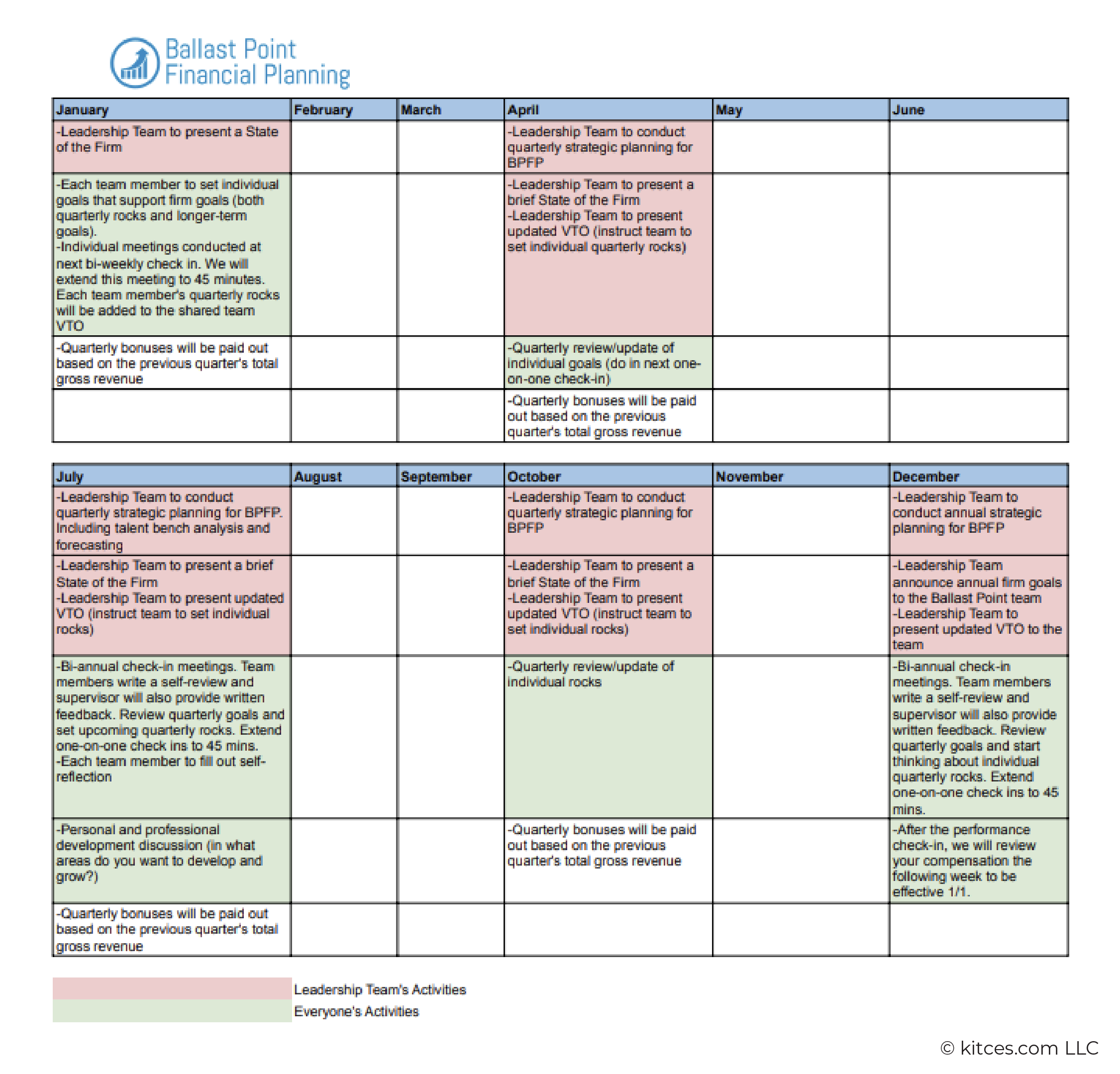

For the size of my firm, I believe we're highly developed when it comes to human capital management, benefits, career tracks (thanks to Herbers & Co), a shared bonus system, a structured HR calendar (thanks to Shannon O'Toole), an HR Manual, a well-organized chart of accounts (thanks to Lori Martz), and we even just rolled out a sabbatical policy (thanks, Chat GPT!).

Takeaways:

- Treat your business like a business.

- Invest time to develop the tools and systems you need to run your business well – and don't be afraid to bring in consultants when needed.

5. Working On Myself (Something I Got Right)

If I'm being honest with myself – and with anyone reading this – for many years while running my business, I wasn't in a very good headspace. I wasn't happy with what I had achieved. I compared myself to others. I think the exposure to Harvard Business School (through my wife, who graduated from there in 2010) warped my sense of what success means. That same year, several of her peers launched companies like Birchbox, Rent the Runway, Blue Apron, and LearnVest.

From the outside, many people might have looked at my situation and said I was successful. But even if people said that to me, those words fell on deaf ears. I didn't feel it intrinsically. I dreaded turning 40. I was worried about getting injured/hurt and not being able to run (more on that shortly).

To help me feel better about myself, I self-medicated with alcohol – especially during COVID. I justified having two or three beers at the end of a hard day by telling myself I had earned it and that it was a celebration, given everything I accomplished that day with my business and running. In a warped way, I even convinced myself that being a little hungover gave me something to overcome and something to be proud of.

A lot of people used COVID as an excuse to drink more. And I definitely was one of them. I was drinking most nights of the week, if not every night. Given my family history of alcoholism, this was something I worried about. And with two small kids, I didn't want a hazy memory of their childhood. I simply wasn't happy with my relationship with alcohol, so on December 12, 2020, I challenged myself to quit for 90 days. It was really hard at first, but I haven't had a drink since.

Still, quitting drinking didn't solve everything. If anything, it exposed deeper unresolved issues in my life. I felt worse about myself, struggled with injuries, and wasn't able to run. After a seven-year streak of qualifying for and running the Boston Marathon, I missed qualifying by 26 seconds in the fall of 2021.

What solved it? There was no silver bullet. I went through years of therapy. I read a lot of books on the meaning of life and midlife transitions and really worked on myself. I rotated through therapists until I found one that clicked. Through some exercises with her, and by confronting some issues from my past, I was able to break out of some of the negative head trash I had and carve out some new, positive-framed neural pathways.

This is still something I'm working on. But when I think back to the version of me from 9-10 years ago, I think I'd be thrilled with where I am right now.

Takeaways:

- Be kind to yourself. It's okay to be ambitious and driven, but revisit your values and drivers as they evolve over time.

- Achieving personal satisfaction and happiness is incredibly hard – but doing the work on yourself is something to be very proud of.

6. I Tried To Grow Too Fast And Hired Too Often (Something I Got Wrong)

In the very beginning, I hired cautiously – outsourcing through Delegated Planning for a few hours a month and Simply Paraplanner to find remote support – before moving into full-time hires. At one point, though, I had eight team members and a total of nine direct reports across Ballast Point and BLX. Yes, nine people reported directly to me. In addition, I was responsible for helping my team with their career development and growth, while also handling all new business development, reviewing client tax returns, and serving as lead advisor for more than 70 relationships.

To cover the financial demands of such a large payroll, we needed to add 10–12 new clients per month. For a short time, we made this work. But, unsurprisingly, that pace was unsustainable for a number of reasons.

First of all, I had assumed that everyone would simply self-manage their workloads and career progress. I had a basic feedback process in place, but it wasn't sufficient. I had quarterly check-ins with each team member, but not consistent one-on-one meetings.

That changed after I met Shannon O'Toole, a presenter at XYPN Live. She helped me build out an HR calendar.

I now meet bi-weekly with each team member for 30 minutes and provide documented feedback twice a year. Each team member is asked to fill out a self-review before their check-in that addresses the points below; their feedback has made a huge improvement to our process.

Ballast Point Six-Month Check-In Survey – Areas Of Assessment:

- Proudest accomplishments

- Strengths/wins/successes

- Areas of improvement

- How the company's values are embodied

- Overall job satisfaction

- Career progress

- Quarterly goals

- Personal and professional development

- How the manager/supervisor can support professional development

- Feedback to share about managers

At the time, my vision for Ballast Point was to grow it into a large-scale enterprise firm as quickly as possible. But after a rough and sloppy tax season with too many amended returns, I had to let someone go. That was the first time I had to let a team member go, and I was sick about it. I tried to make things work with documented feedback, hard conversations, and lots of coaching, but it just wasn't a good long-term fit.

Not long after, I had to let go of another team member. We also had an intern who was difficult to manage and develop. On top of that, two other team members left on their own. So Ballast Point went from a team of nine (a full Brady Bunch of Zoom squares) down to a team of four.

To help manage the workload, we considered selling some of our clients to another firm, but after internal conversations with the team, we decided to absorb everyone and transition them to a new advisor. One thing I learned from this experience is that client trust does transfer. When there is a change in the lead advisor for a client, it's natural for some clients to graduate – often because they're ready to self-manage, or occasionally because they choose to follow their advisor to a new firm. However, I would say that we have about a 90% client retention rate when the client is reassigned to another advisor at Ballast Point.

While team and client turnover is hard, I've tried to keep an abundance mindset through it all. I want clients to work with the advisor who is best suited for them, which is why I don't enforce any non-compete or non-solicit agreements. I believe the advisors who left my firm didn't proactively try to reach out to clients. And if clients decided to follow them on their own, I respected that.

Looking back, another hard truth is that I wasn't paying my team enough, something I wasn't happy about either. I reinvested everything back into the business. But with such a rapid hiring spree, I couldn't afford to pay my team market rates. Part of that challenge came from fee confidence: I started my firm charging just $150 per month, and only over time, with multiple fee increases, did I build confidence in pricing that better reflected our value and allowed me to pay my team competitively. And after my second child was born and we purchased a larger home, it really required me to focus on the profit side of the business for the first time.

Takeaway:

- Client trust does transfer. With the right structure, clients can be clients of the firm, not just of an individual advisor. Don't let fear of client loyalty prevent you from building thoughtfully.

- Growing too quickly can stretch both finances and leadership capacity. Building a team takes more than just hiring people – it takes fair compensation, clear expectations, and consistent feedback systems.

7. Managing Team Turnover (Something I'm Still Learning From)

One harsh reality of being a business owner is the challenge of talent management. On more than one occasion, I was blindsided when a team member submitted their resignation. I thought we had friendly and open relationships – that they could come to me if something wasn't working. Maybe that was naive. From their perspective, they were likely protecting themselves and their own financial livelihood. Or perhaps they assumed there was no option for changes to their job duties.

Still, I would have appreciated the opportunity to have a conversation about working on things together. We could have experimented with adjusting responsibilities, gathered feedback, reassessed, and reevaluated before deciding whether it was a good long-term fit. Instead, on at least four occasions, team members gave notice with their minds already made up. In every case, they didn't even have another job lined up – which was hard for me to process.

I'll admit, those moments were really hard on me. I was hurt, and I probably could have handled the resignations better. It is really difficult not to take it personally.

Takeaway:

- Employees won't stay with you for life, even with a culture of open communication. Don't assume team members will always tell you if something isn't working.

- To get ahead of surprises, I now check in twice a year with each team member about their job satisfaction.

8. Tempering The Cost Of Isolation (Something I'm Still Learning From)

When I launched my firm, I had such a fire inside of me that I wanted to move at 100 miles per hour. While I really loved my launchers group, over time, I felt like I had outgrown them, especially as I was the only one striving to build an enterprise firm. One regret I have is leaving that group. In an effort to regain control over my time and calendar, I also didn't replace it with a new study group – and to this day, I don't have one.

For years, I also didn't have a business coach. In fact, I've had a hard time finding a business coach who feels like a good mutual fit, and I've rotated through many.

Eventually, I left XYPN altogether. Part of it was financial – I wasn't getting enough value from the network for what I was paying. Another part was that I felt I had outgrown the network. XYPN is great for the first one or two years of launching a solo advisory firm, but it didn't seem to have as many resources for advisors who wanted to grow enterprise or multi-advisory firms.

The main reason, though, was the lack of support I felt from the network when we launched the BLX Internship Program in the fall of 2020. At the time, XYPN indicated that they didn't have resources to support us, which was disheartening given what was happening in the country with the Black Lives Matter movement and a contentious election.

With a heavy heart, I decided to leave. I love the XYPN community, but I didn't want to support the network financially any longer.

Takeaway:

- If I had to do it over again, I would have tried to make it work a little longer with my study group or tried to find a new study group.

- Don't compromise your core values. If a group no longer aligns with them, it's okay to move on in a respectful way.

9. Comparing Myself To Others (Something I'm Still Learning From)

"Comparison is the thief of joy."

For years, I eagerly listened to XYPN and Kitces podcasts and compared myself to others – those who launched around the same time, and those who started before me. I defined 'success' for myself as growing faster than they did, whether that was in terms of revenue or clients served. I would constantly compare my position with where other launchers were. I excluded anyone for comparison purposes who didn't start from scratch like I did. Or, if they had a co-founder, I would tell myself that they were doing something different from me.

It's still something I'm working on. As a striver – living in the Bay Area, having the Harvard Business School experience, and heck, maybe it's because I even have an older brother – I've always had a hard time feeling satisfied with where I'm at.

However, given the stage and season of life I'm in now, I can truly say I feel happy. After a lot of personal work, I finally feel content with where I am at.

I recently learned of the "garden and the flower" framework. At this stage, I'm the gardener for my family's household. My wife loves her job and is thriving professionally, but it is very demanding (with a one-hour commute each way). That leaves more of the child-rearing duties to me. Sometimes I enjoy it and feel like it has helped my relationship with my kids. Other times, it builds resentment. As two career-driven professionals without local family support in the Bay Area, we've had to figure out systems to raise our family. We've outsourced a ton and are currently experimenting with a "family helper" who makes dinner and does dishes up to three nights a week during the workweek.

Takeaway:

- Success looks different for everyone. Figure out your own definition of success and be willing to keep refining that definition over time.

Where Do I Go From Here?

I still have a nagging itch to 'go big'. However, I don't have the energy or appetite to pursue that right now. I'm happy with the balance I currently have.

But stay tuned. I remain passionate about addressing the lack of entry-level opportunities in our profession and am working on ways to help solve that issue. I have a vision for a "Financial Planning Collective" – an incubator for new advisors to learn the business, get licensed, earn a decent salary, and grow their careers without the pressure of immediately developing new business. My hope is to create an ecosystem where advisors can truly thrive and we can address the talent gap in our profession!