Executive Summary

Investors nearing or in retirement often face the challenge of balancing their aversion to short-term losses with the need to maintain exposure to growth assets to meet long-term goals. Traditionally, portfolio managers have used a mix of equities and less volatile assets like bonds to dampen portfolio swings while retaining at least some of equities' upside potential.

However, even stock-bond portfolios still carry some risk of loss, at least in the short term, which can rattle investors who are sensitive to declines in their investments' value. Fixed income doesn't experience the same kind of drawdowns as equity during periods of market volatility, but most bonds and bond funds can still lose value (other than individual Treasury bonds, whose principal is guaranteed by the U.S. government). Furthermore, while bonds and equities have been negatively correlated for much of the 21st century – offering portfolios a natural buffer with bonds experiencing positive returns when equities go negative and vice versa – the correlation has flipped to positive in recent years, increasing the chances that all parts of an investor's portfolio are in the negative at once – making it even more psychologically difficult for investors to stay the course during periods of volatility.

One increasingly popular response has been the rise of 'defined outcome' ETFs, which use structured derivative strategies like option collars to set boundaries around both downside risk and upside return. Among these, 'downside protection' ETFs have gained attention for their promise of protecting investors from loss while offering some equity market participation, typically capping positive returns at a given rate (currently around 7%). Compared with similar alternatives like Fixed Income Annuities (FIAs) or DIY option collars, downside protection ETFs are often more liquid, scalable, and tax-efficient, giving them a powerful sales pitch to risk-averse investors.

However, a closer look at the mechanics of the funds currently on the market uncovers traits that undercut the sales pitch. Because the ETFs are based on option strategies with specific beginning and end dates, their stated upside and downside limits are only fully available to investors who buy them at the very beginning of the cycle. Within the year, prices can still fluctuate, meaning the promised psychological comfort only holds if investors don't look at their account value throughout the year!

The promise of 'equity participation' is also more limited than it appears. With performance caps currently in the 6–7% range, downside protection ETFs lag equity returns in most historical rolling one-year periods. Investors who buy mid-cycle may even see losses relative to their entry price, despite the 'no loss' marketing. And unlike bonds or Treasuries, which offer guaranteed income and principal preservation, downside protection ETFs can deliver flat or even negative real returns after fees if markets are flat or slightly down.

Ultimately, downside protection ETFs can serve a niche purpose, such as holding short-term funds earmarked for near-term goals where principal protection is critical and the investor is comfortable sacrificing upside. But they are not a true substitute for equity exposure, and their complexity can mask the relatively modest benefits they offer compared to more traditional fixed income strategies. For advisors, the deeper value lies not in outsourcing risk management to a product, but in reinforcing disciplined investment management and behavioral coaching. By helping clients stay invested through market volatility – armed with a long-term perspective and a thoughtfully constructed portfolio – advisors can deliver not only better outcomes but also greater peace of mind than a 'defined outcome' ETF can promise.

Risk Vs Return In Investing

In investing, risk and reward go inextricably hand in hand. Assets with higher expected returns over the long run are likely to have a higher risk of loss in the short term. Likewise, assets that are 'guaranteed' never to lose value, such as cash and Treasury bonds, tend to have the lowest returns over time.

This tradeoff is what makes it possible to grow wealth via investing. If one invested solely in cash and Treasury bonds guaranteed never to lose value, the investments' growth would at best barely keep up with inflation (and may even lose purchasing power over the long term), forcing the investor to save a significantly higher percentage of their income to meet retirement and other goals.

By contrast, investing in riskier assets like equities – essentially giving capital to businesses to fund and grow their operations in exchange for a slice of their future growth – allows investors to participate in that growth, even though the investment may decline in value or become worthless if the economy contracts or the company goes bankrupt.

The relationship between riskier and less risky assets has been well studied, notably since the 1950s with the introduction of Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) by Harry Markowitz. The implication of MPT is that investors can use a mix of more and less risky assets to target an expected level of overall portfolio volatility that matches their capacity or tolerance for risk. In other words, if investors don't want to or can't accept the risk of their portfolio declining by 50% or more (as is possible with an all-equity portfolio), they can add less risky assets like bonds to temper overall volatility.

All of which is why portfolio management over the last 50+ years has predominantly allocated some percentage of the portfolio to equities, and the remainder to bonds and/or cash. Having some assets that won't lose value when the equity markets decline (or at least won't decline as much) serves as a natural damper on portfolio volatility, while keeping some portion in equities allows investors to keep at least some of the upside potential of exposure to riskier assets. And by maintaining those allocations over time through occasional rebalancing, investors can preserve a steady level of expected risk in their portfolios – and conversely, a reasonable long-term return expectation they can use for planning purposes.

Challenges Of The Stock-Bond Portfolio

While the equity-bond mix has proven a useful way to blend risk and return expectations for long-term planning and has achieved overwhelmingly positive long-term returns historically, it's still riskier than investing only in guaranteed assets: Blended portfolios can, and do, go down from time to time. As such, some investors with extreme sensitivity to downturns – even when the portfolio is likely to bounce back in the long run – can have trouble accepting a stock-bond portfolio as the answer to their investing needs.

One challenge is that bonds themselves can lose value. U.S. Treasury bonds, when held to maturity, are guaranteed to return principal and interest and have never experienced a default. But other types of fixed income – from corporate to municipal to mortgage-backed securities – can default, leaving the investor with less than (or none of) their original investment back. And when traded rather than held to maturity, as in most bond mutual funds and ETFs, bonds – even U.S. Treasury bonds – can lose value on a mark-to-market basis based on prevailing interest rates and the perceived creditworthiness of the issuer. So while fixed income assets have historically been less volatile than equities, the bond sleeve of a portfolio can still produce negative returns over months- or even years-long stretches.

It's easier to accept losses in fixed income when fixed income itself serves as a hedge against equity declines, generating positive returns when equity declines. And for most of the 21st century, the bond market has been negatively correlated with equities – that is, fixed income has performed positively when equities have declined, and vice versa. For most of that time, then, losses in bonds at worst served to dampen (though not completely offset) the positive returns generated by equities. And when equities have declined – even in major market crashes like the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and the 2020 onset of the COVID pandemic – fixed income has performed positively and dulled equity's losses for investors who have maintained a mixed stock-bond allocation.

However, since around 2021, correlations between equities and fixed income have flipped positive, meaning both markets are likelier to rise or fall together. Which makes portfolios riskier for any given level of stock-bond allocation – because losses in one part of the portfolio are no longer offset by gains in the other. It also makes fixed income seem riskier, since it now appears to amplify rather than tamp down on equity losses.

That doesn't mean a stock-bond mix is no longer a viable way to manage a portfolio. Correlations were mostly positive throughout the 20th century when many of today's portfolio management practices were established, and the core purpose of fixed income to lower overall portfolio volatility hasn't changed. Mathematically, as long as the portfolio's volatility is within the investor's risk capacity – particularly near and during the first years of portfolio withdrawals – investors can absorb the marginal extra risk without jeopardizing their investing goals.

But regardless of what the math says, investors still face a behavioral challenge: accepting the risk of short-term losses to achieve long-term gains. One of the biggest challenges for financial advisors can be keeping clients invested in the market – even during the worst periods of market volatility – to avoid missing out on the likely eventual recovery. When an investor sees negative numbers across all of the assets in their portfolio, equities and fixed income included, they're more likely to sell out and move to cash than if some of their assets are at the very least not losing any value. In other words, even though fixed income can provide enough of a volatility buffer to keep a portfolio within the investor's risk capacity, its (modest) fluctuations can still feel like too much for investors who get nervous about short-term downturns.

Option Strategies As A Psychologically Appealing Volatility Dampener?

Investors wanting more rigid downside protection than a stock-bond portfolio can offer (without simply moving to cash) can limit their exposure to loss with derivative-based strategies using put and/or call options. But the rule of risk versus return applies here, too: To protect against loss, investors must give up some of the potential for higher returns.

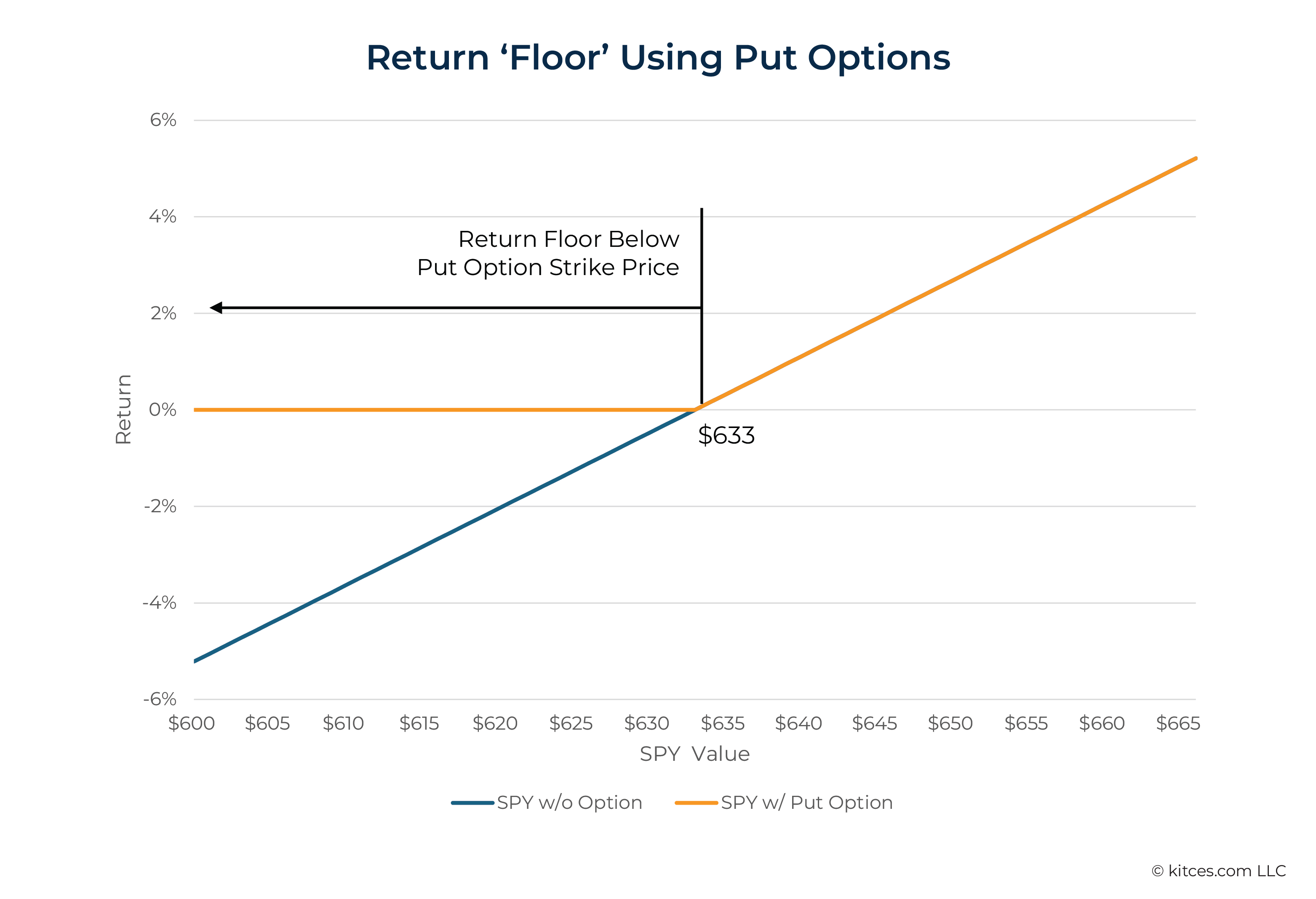

A put option is a contract that gives one party the right – but not the obligation – to sell a given security (known as the 'underlying') to the other party for a specified price (the 'strike' price) after a specified time period (the 'expiration'). For example, imagine an investor buys a one-year put option on the SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY) at a strike price of $633. If SPY closes higher than $633 at expiration, the option expires unused – the investor would be better off selling SPY at the market price. But if SPY closes lower than $633, the investor can exercise the option and sell at the strike price. In effect, the put sets a floor on losses, with the strike price determining where the floor lies.

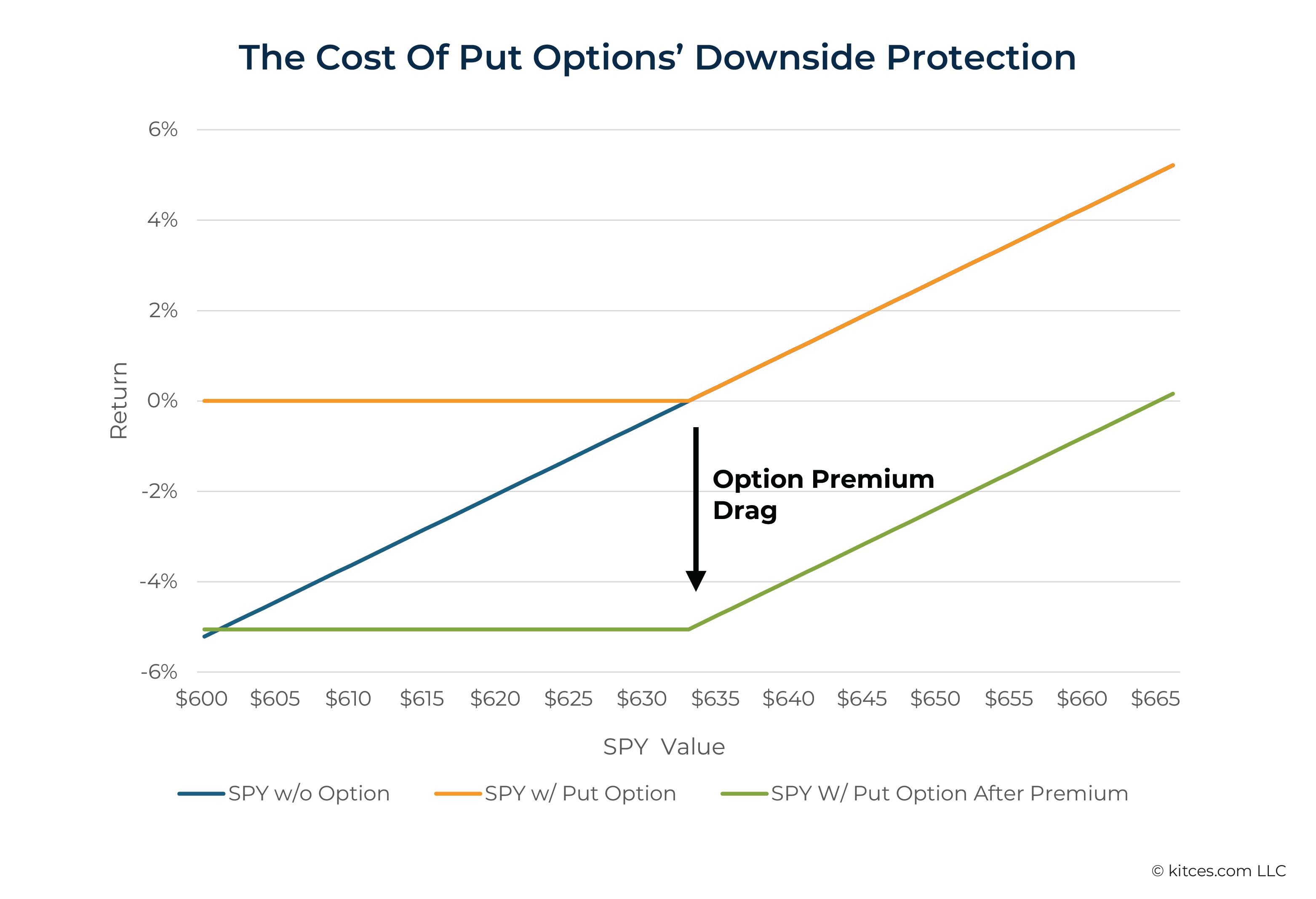

But here's where the risk/return tradeoff comes in. Although put options can provide downside protection, they have a cost in the form of the option's premium. And that cost can impose a serious drag on overall returns.

Example 1: Sarah owns 100 shares of the SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY), with a current market value of $633 per share, for a total market value of $63,300. To protect her investment from loss, she buys a one-year SPY put option with a $633 strike price for her 100 shares at a price of $32 per share, or $32 × 100 = $3,200 total.

If SPY closes below $633 at expiration, Sarah can exercise the put option and sell SPY for a total of $633 × 100 = $63,300. But after factoring in the cost of the options, she only ends up with ($633 – $32) × 100 = $60,100, a 5% loss.

Even if the underlying security finishes above the option's strike price, the cost of the option premium still eats into the investor's return. And because all options expire at some point, the investor must keep paying the option premium each time they renew it to maintain the downside protection they want – even though that 'protection' still allows for a potential loss after accounting for the premium cost. And the more volatile the market, the higher the premium, meaning that in turbulent market conditions, when investors demand the most downside protection, it becomes more expensive to buy that protection, eating that much more into the investor's overall return.

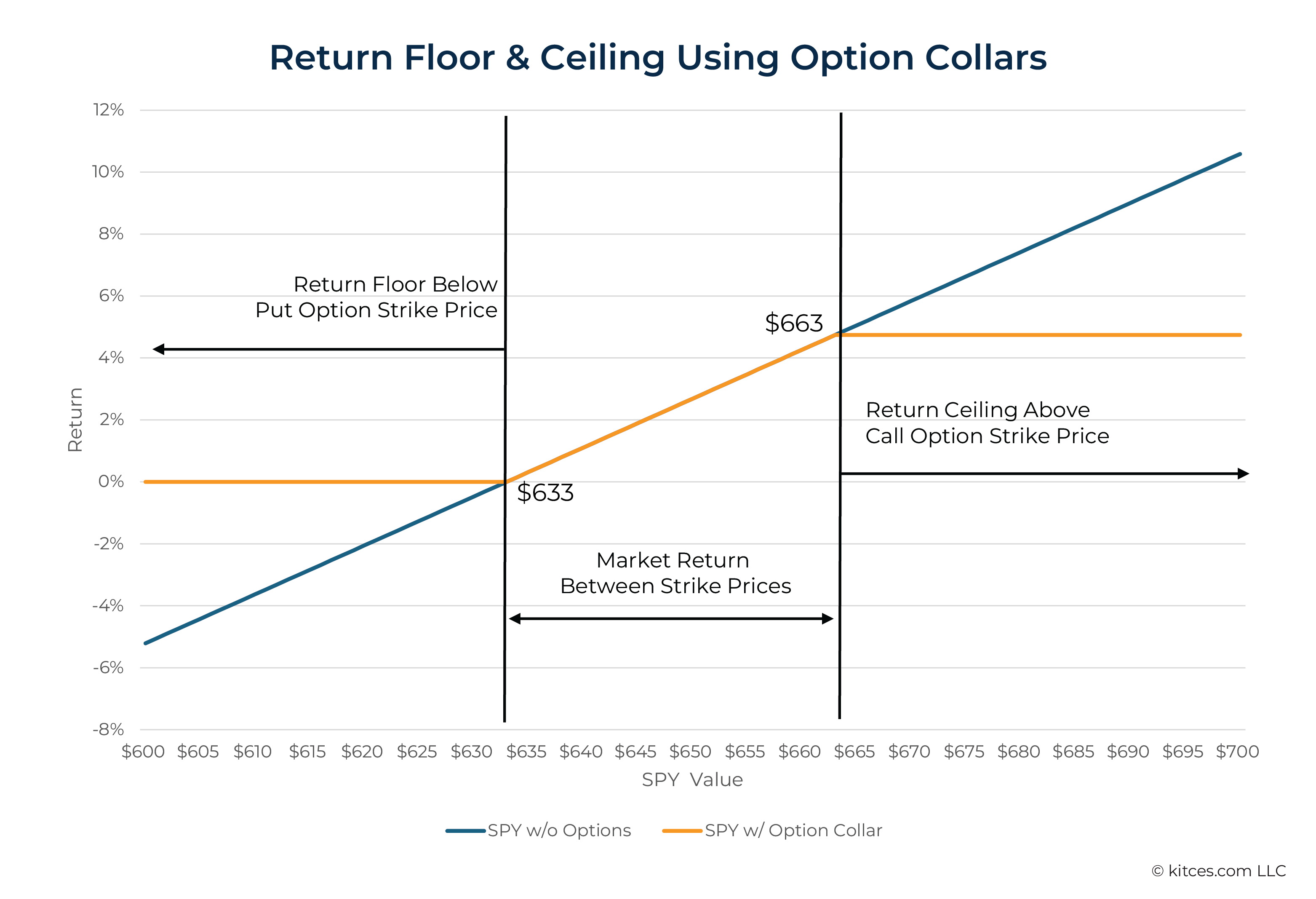

One way to offset the cost of buying put options is to sell a different option, most commonly a call option, which generates income to cover the cost of the downside-protecting put option. Call options work in the opposite way as put options: The buyer has the right to buy (rather than sell) the underlying security at the strike price upon expiration. By selling a call option for the same price as the cost of simultaneously buying a put option, the investor can reduce or eliminate the drag on returns created by the put option's cost.

Example 2: Sarah, from Example 1 above, buys a one-year SPY put option with a $633 strike price for $32 per share for her 100 shares, or $3,200 total. At the same time, she sells a one-year call option with a $663 strike price, which pays her $32 per share, also totaling $3,200.

The income from the call option offsets the cost of the put option, resulting in zero net cost for the strategy.

However, just as buying a put limits the downside of the underlying investment, selling a call sets a hard cap on the investment's upside potential. If the underlying security closes higher than the call's strike price, the seller must sell the security at the strike price, losing any additional return beyond that amount. The end result is a strategy with limits on both the potential downside (via the put) and upside (via the call), commonly called a 'collar' due to the constraints on both ends.

Example 3: Sarah, from Examples 1 and 2 above, buys a one-year put option on her 100 shares of SPY with a $633 strike price, and sells a one-year call option with a $663 strike price.

After one year, Sarah will receive a minimum of $633 × 100 = $63,300 for her SPY shares (if SPY closes below $633), and a maximum of $663 × 100 = $66,300 (if SPY closes above $663).

If SPY closes between $633 and $663, the shares will simply be worth their market value, and both options will expire unexercised.

In sum, an option collar strategy provides a narrow range of exposure to the underlying security, whether a single-company stock or a broad-based ETF like SPY. The investor only receives the actual return of the underlying security if its price is between the strike prices of the two options upon their expiration. Otherwise, they receive either the minimum set by the put or the maximum set by the call.

Put simply, an option collar limits how much an investor can gain or lose on the underlying security. Instead of incurring the risk of loss and benefiting from the upside potential that comes with it, investors accept a defined range of outcomes that caps both the risk they incur and the amount of return they can realize. While not offering the full upside potential of equity exposure (which is capped by the call option), option collars do have the potential advantage of offering 100% downside protection, which is otherwise only the case for risk-free assets like cash and Treasury bonds.

This makes option collars a potentially appealing strategy for investors who value the psychological security of downside protection. This is how such strategies are often pitched and sold to investors: as a way to maintain some equity exposure while simultaneously being protected against any loss of principal.

Operational Challenges Of DIY Option Collars

Option collar strategies have long been employed by both retail investors and professional asset managers seeking to limit their downside exposure in exchange for capped upside. This tradeoff has its own set of issues, discussed further below. And for those who do use them, option collars present additional operational challenges that make them hard to execute at the scale of an independent advisory firm.

First, there's the task of implementing the collar strategy itself. Because standard options expire by definition, each time the collar's options run out, the investor must buy and sell a new put and call to keep the strategy going. With most collar strategies lasting from around six months to two years until expiration, this process recurs about as frequently as regular portfolio rebalancing, but with more complexity – including the need to price and compare each round of options to ensure that the call income fully offsets the put's cost.

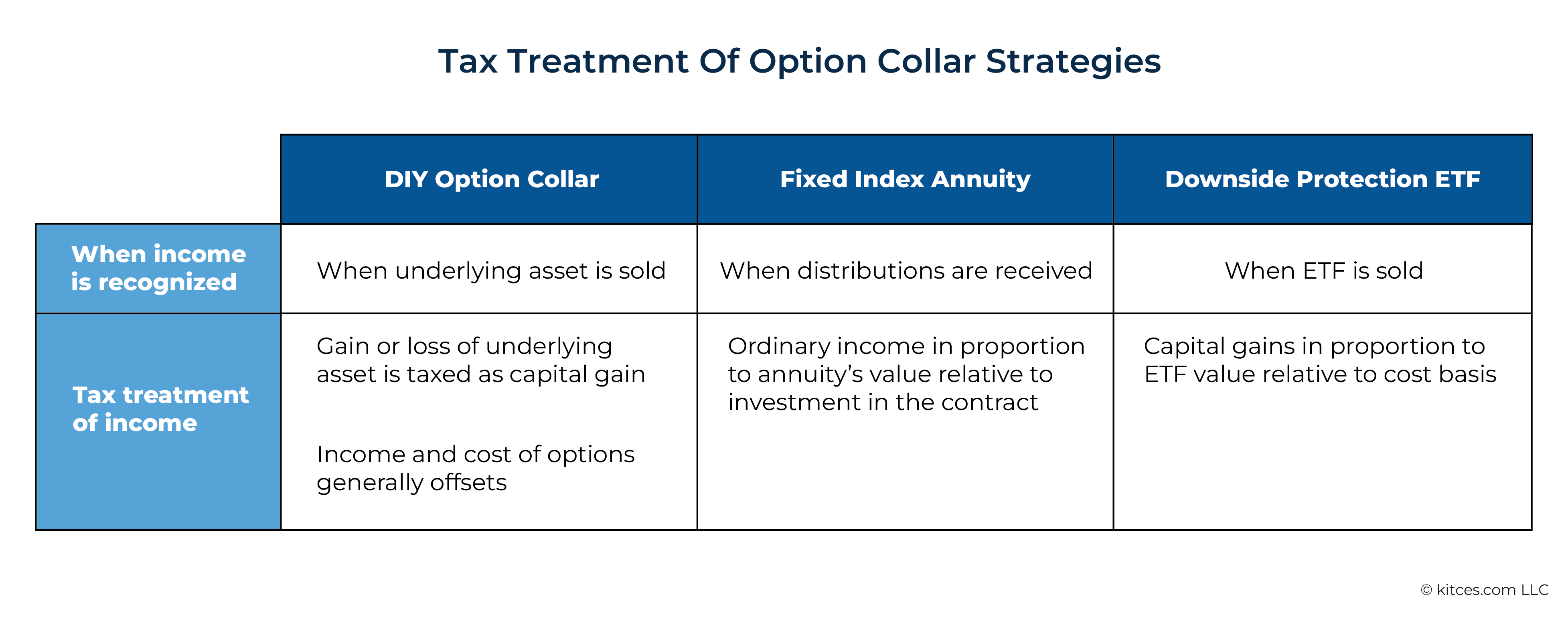

Option strategies in taxable accounts can also have significant tax consequences. If exercising either the put (when the underlying investment falls below the put option's strike price) or the call (when it rises above the call option's strike price) triggers a sale of the underlying investment, the investor is taxed on any realized gain.

Example 4: Sarah, from Examples 1–3 above, owns 100 shares of SPY at a current value of $633 per share and a cost basis of $500 per share. As in the previous examples, she buys a one-year put option on SPY with a $633 strike price for $32 × 100 = $3,200, and sells a one-year call option with a $663 strike price, also for $32 × 100 = $3,200.

On the expiration date of the options, SPY is trading at $615, and Sarah exercises her put to sell at $633 per share. She avoids the loss on her investment, but in doing so, realizes capital gains income of ($633 − $500) × 100 = $13,300. At a 15% long-term capital gains rate, she will owe $13,300 × 15% = $1,995 of tax on the sale.

Thus, the defined range of outcomes provided by the collar strategy can result in a tax bill whenever the underlying investment's price moves outside the collar's boundaries. While the investor can always buy back the shares after the sale if they want to continue the collar strategy, they'll still be taxed on any gains incurred each time an option is triggered. And if losses are realized on the original investment when it's sold, buying the investment back within 30 days of the sale would trigger a wash sale, causing the loss to be disallowed.

Nerd Note:

The options in a collar strategy also have their own tax impact. Call option income is either added to the realized gain of the underlying security if the option is exercised, or if it's taxed as short-term capital gain if it expires. The put option's cost is either added to the cost basis of the underlying security if exercised or treated as a separate capital loss if it expires.

In a pure 'no-cost' option collar, the tax consequences of the put and the call effectively cancel each other out. But if the put option's cost and the call option's income don't exactly match, additional gain or loss may be realized beyond that of the underlying investment. For more information, see IRS Pub. 550, beginning with the section titled "Options".

These challenges make it hard for advisory firms to scale collar strategies without a dedicated trading team or outsourced investment management through a Separately Managed Account (SMA). Their tax complexity creates additional challenges when using them in taxable accounts. Which might be one of the reasons why bespoke option collar strategies are relatively uncommon among financial advisors and their clients.

Downside Protection ETFs As An Operationally Efficient Wrapper For Collar Option Strategies

Most financial advisors may not want to create their own option collar strategies for clients, given the lack of scalability and potential tax inefficiency. However, other vehicles exist that can deliver similar results in a 'packaged' solution, eliminating the need to construct and manage an option collar on their own.

For example, Fixed Index Annuities (FIAs) employ similar option-based strategies to offer downside protection guarantees with capped upside. The chief advantages of FIAs are that the annuity provider effectively handles the option collar mechanics, and any gains realized within the annuity are tax-deferred rather than being taxable in the year they're incurred. However, as annuity products, FIAs generally come with multiyear lockup periods that prevent the owner from taking any withdrawals without incurring a surrender charge. Additionally, once withdrawals do begin, any growth on the strategy is taxed at ordinary income tax rates rather than capital gains rates. So, for investors with shorter time horizons (for whom guaranteed downside protection might have the most appeal), and especially for those in higher ordinary income tax brackets, FIAs might not be the best option.

More recently, option collar strategies have increasingly become available within an ETF wrapper in the form of downside protection ETFs. These are an offshoot of the blossoming category of 'buffer ETFs', which are ETFs that track an index and offer protection against a certain percentage of losses in exchange for capped upside over a defined time period (most often one year). Downside protection ETFs take the idea further, aiming to protect against 100% of losses rather than only up to a certain limit. Like a standard option collar, the maximum return is capped at a certain percentage to pay for the cost of the 100% downside protection.

Several sponsors offer downside protection ETFs, including Innovator ETFs, Calamos, iShares, and First Trust. Each fund has certain specified terms:

- Return period: the start and end dates of the options that the ETF uses to implement its strategy (commonly one year, but can range from six months to two years);

- Reference asset: the investment whose performance the ETF is designed to track, usually an S&P 500 index ETF like SPY;

- Performance cap: the maximum return of the fund over the return period;

- Minimum floor: the lowest return possible over the period (commonly 0% before fees); and

- Expense ratio: the fund's annual operating cost, expressed as a percentage of assets. This fee reduces both the minimum floor and maximum performance cap (e.g., the return of an ETF with a 0% floor, a 7% cap, and a 0.5% expense ratio will actually range between –0.5% and 6.5%).

These criteria are key when comparing downside protection ETFs to each other, as well as to other options like DIY option collars or FIAs.

The Importance Of Timing In Downside Protection ETFs

Because option collars are time-based strategies with a beginning and end point based on the respective purchase and expiration dates of the options, downside protection ETFs are also structured around a start and end date. For example, Innovator ETFs sells a series of 12 downside protection ETFs with one-year terms, each starting in a different month. The ETF implements the option strategy at the beginning date, and at each reset, when the fund's options expire, the ETF executes a new set of options and rolls the strategy forward into a new term.

Since the ETFs operate perpetually, rolling over from one time period to the next, the ending value of one term becomes the starting point of the next. For example, if the ETF reaches its maximum cap in Year 1, that capped amount becomes the new minimum floor in Year 2. Thus, downside protection ETFs operate like a perpetual option collar that automatically rolls forward until the investor sells the ETF.

Example 5: Otis buys a one-year downside protection ETF with a 0% floor, 7% performance cap, and SPY as the reference asset starting at $25 per share.

During Year 1, SPY returns +15%, which is above the ETF's 7% performance cap. The ETF's price at the end of Year 1 is $25 × 1.07 = $26.75, which becomes the starting price for Year 2.

During Year 2, SPY returns –7%, which is below the 0% performance floor. The ETF's price at the end of Year 2 remains at $26.75, which is the starting price for Year 3.

During Year 3, SPY returns +5%, which is between the ETF's 0% performance floor and 7% performance cap, so the ETF's price at the end of Year 3 is $26.75 × 1.05 = $28.09.

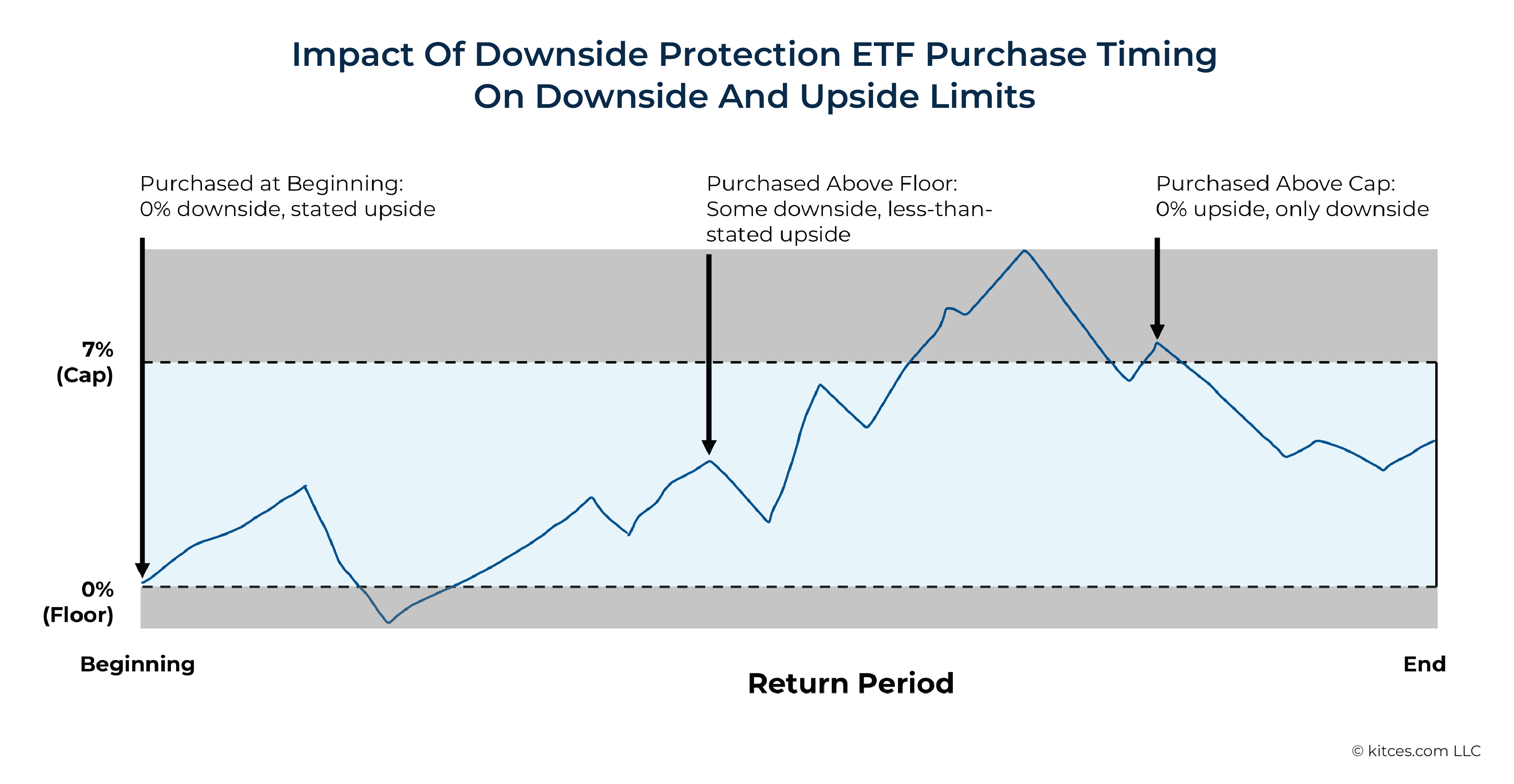

The caveat, however, is that to actually achieve the advertised performance results of a downside protection ETF, the investor must buy the ETF at or near its price at the beginning of its return period. That price, and not the price where the investor actually buys the ETF, is what the fund's upside cap and downside floor are based on.

Example 6: Aretha buys a downside protection ETF on January 1, the first day of the return period, at its opening price of $25 per share. The ETF has a performance cap of 7% and a floor of 0%.

Because Aretha bought the ETF at the same price that its performance cap and floor are based on, she'll receive the same downside protection and maximum upside as the fund itself.

Investors who buy a downside protection ETF at a different price from where it begins its return period, however, won't have the same set of defined outcomes as the fund itself.

For instance, if the market continues to go up, the investor may not be able to realize the ETF's full performance cap if they buy the fund when its price has already risen above its initial level.

Example 7: Etta buys the same downside protection ETF as in Example 6 above, which has a 7% performance cap. However, instead of buying it on its starting date of January 1, she buys it six months later on July 1, when its price has risen to $26 per share.

Since the ETF's initial price was $25, it has already risen by ($26 ÷ $25) − 1 = 4% out of a maximum of 7%. Once the ETF reaches $25 × 1.07 = $26.75, it cannot go any higher.

Therefore, the maximum return that Etta can realize is ($26.75 ÷ $26) – 1 = 2.9%, not the ETF's stated 7% cap.

Likewise, if the price of the ETF is above the fund's minimum performance floor, the investment can still lose value down to that floor.

Example 8: Using the same ETF as in Example 7 above, Etta buys at $26.

The ETF's floor is its price at the beginning of its return period, which was $25. If the market declines after Etta purchases the ETF, she could realize a negative return as low as ($25 ÷ $26) – 1 = –3.8% before the price reaches the floor.

There's no 100% downside protection for an ETF that's risen above its original performance floor!

When buying a downside protection ETF, it's essential to know how much upside remains and how far the fund can decline before hitting its minimum floor. As shown in the graphic below, the stated downside protection and upside limits only really apply at the outset of the ETF's return period. And at the extreme, buying after the ETF has already reached its maximum performance cap could mean zero upside and only downside risk, since, at best, the price might stay at the same level (if the market stays above the fund's performance cap) and, at worst, it could decline all the way down to the fund's performance floor.

To that end, it's most often best to buy a downside protection ETF at the very beginning of its return period rather than at some point in the middle. However, if the market has remained relatively flat, and the ETF is close to its initial price, it may still be possible to buy it and at least get most of the downside protection and upside potential offered by the fund.

It's also important to note that downside protection ETFs don't necessarily move perfectly in line with the index they're tracking throughout their performance period. Option prices tend to move more the closer they are to their expiration date. In other words, if the markets have risen by 3% since the start of an ETF's return period, it's unlikely that the ETF itself will have risen by 3% as well. Even if the market jumps above the ETF's maximum performance cap immediately after the beginning of the fund's return period and doesn't come back down, investors will likely need to hold the ETF for the entire return period to actually realize the fund's maximum performance.

Other Characteristics Of Downside Protection ETFs

Beyond how downside protection ETFs operate, there are some practical details worth noting. In particular, tax treatment and fees can both have a meaningful impact on how these funds ultimately perform.

Tax Treatment

The ETF structure has several advantages over both DIY option collars and FIAs. Like FIAs, the process of creating and maintaining the option collar is outsourced, in this case to the ETF manager. Additionally, like FIAs, any capital gains within a downside protection ETF tend to be tax-deferred because of the ETF's ability to make in-kind redemptions. If the ETF is held in a taxable account, there are generally no tax consequences until the ETF is sold, at which point any gains are taxed at capital gains rates. This is an advantage of ETFs over FIAs, where gains are taxed at ordinary income rates when withdrawn.

Fees

The maximum cap and minimum floor on a downside protection ETF's performance are typically shown on a before-fee basis. The actual limits are lowered by the ETF's expense ratio. For example, a downside protection ETF with a 0% floor, 7% cap, and 0.5% expense ratio will actually deliver returns ranging from –0.5% to +6.5%.

Why Downside Protection ETFs Aren't A Substitute For Equity Exposure

After making sense of how downside protection ETFs work, the question becomes: Do they actually make sense to use – and if so, when?

'Downside Protection' Depends On Your Starting Point

As the name implies, the main benefit of downside protection ETFs is their guarantee to protect against loss. But as noted earlier, that protection only applies from the start to the end of the return period. In between, the ETF's value can still fluctuate between its minimum performance floor and maximum cap. Put differently, the downside that the ETF protects against is entirely in relation to the beginning of the ETF's return period, not the value of the ETF owner's investment over any other time period.

For instance, the ETF could rise for the first few months of the year and then decline over the next few months. The investor would still see a loss in those months, even though the total value of the ETF wouldn't go below their initial investment. The extent of the downside protection depends entirely on the reference point: compared to the initial investment, the ETF won't lose value, but if the fund has appreciated at all since the start of its return period, there's no guarantee it won't decline back down to where it started.

Additionally, if an investor buys a downside protection ETF at any time other than the start of its return period, it won't necessarily provide the full 100% downside protection. In fact, the investment could actually lose value compared with the price at which the investor bought it.

So if the goal of a downside protection ETF is to spare investors from the sight of negative returns, it only succeeds for those who both 1) buy the fund at the start of its return period, and 2) look only at the value of their investment at the start and end of that period. It's not a ratchet that moves only in one direction: As long as the underlying asset's return (e.g., SPY) stays within the ETF's performance floor and cap, the ETF's value will continue to move up and down like any other investment.

Will an investor feel more comfortable with a quarterly loss if they're assured of a no-lower-than-0% (before fees) annual return? Perhaps – but at that point, the ETF's offer of downside protection is based on a more or less arbitrary set of starting and ending points rather than actual protection against loss. And if the investor is willing to accept some short-term loss for the continued possibility of (limited) upside, well… that's the same proposition offered by a traditional mix of stocks and bonds.

So while there may be some logic in using a downside protection ETF to protect a specific amount of investment principal from loss (e.g., a chunk of funds for a down payment on a home), it doesn't make as much sense as a long-term investment strategy, since the 'protection' only applies to whatever the value of the investment happens to be as of the start of the return period.

The Misleading Promise Of 'Equity Participation'

Along with protection against loss, the other side of the pitch for downside protection ETFs is their promise of 'participation' in equity market returns, which gives them theoretically better upside potential than assets like bonds. But in reality, this participation is extremely limited compared with the actual performance potential of equities.

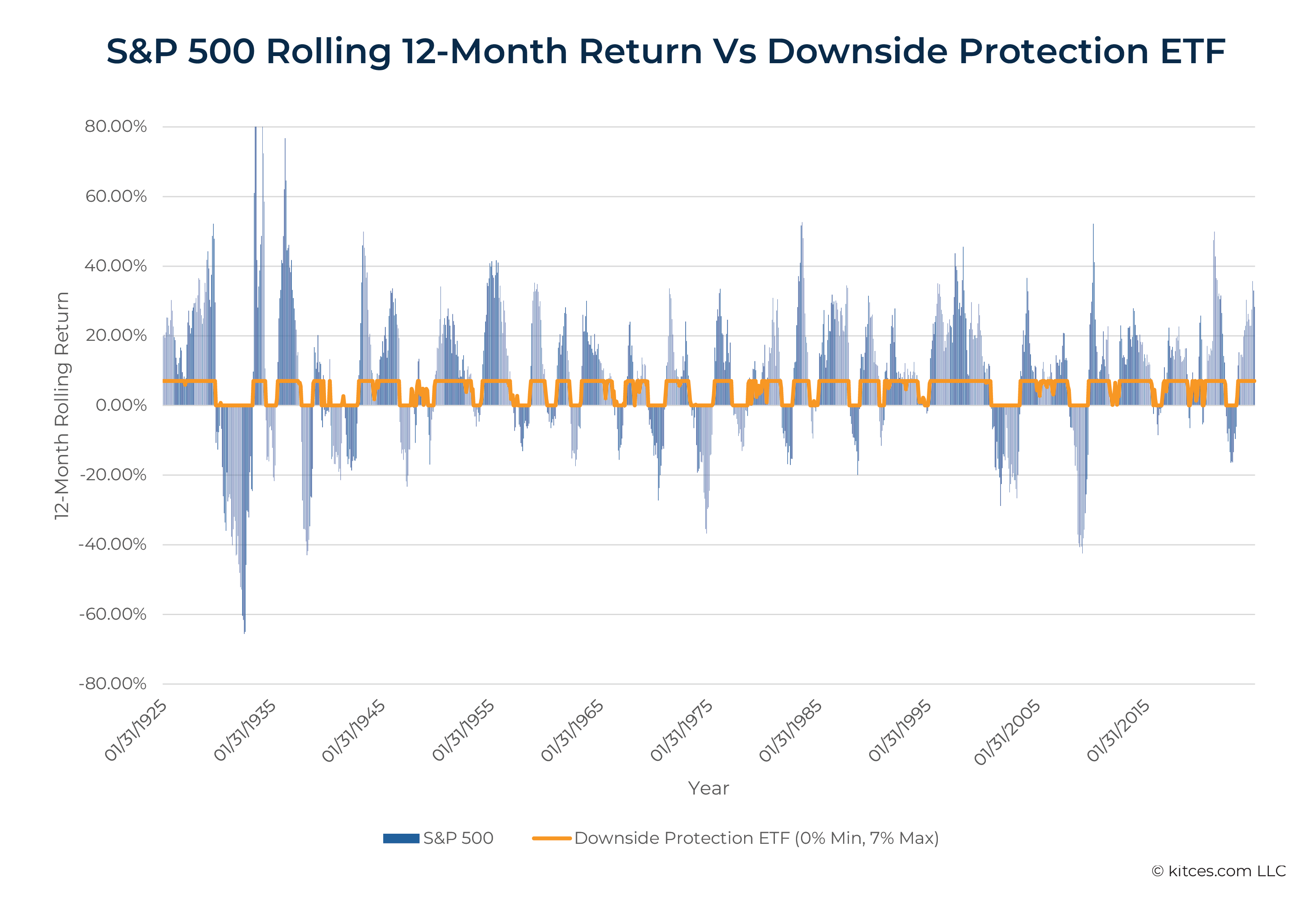

As of this writing, the performance caps on downside protection ETFs are approximately 7%. That means if the reference asset (usually an S&P 500 ETF) exceeds a 7% return, the fund tops out at 7%. If the reference asset is negative, the fund returns 0%. And if the reference asset lands between 0% and 7%, the fund matches the same amount (minus fees in all cases).

Using historical market data from Robert Shiller, out of 100 years of rolling 12-month S&P 500 return periods going back to 1925, 58% would have exceeded a 7% return cap, while 29% would have returned lower than a 0% floor. In only 13% of rolling 12-month periods would a downside protection ETF have actually returned the market rate, between 0% and 7%.

Notably, performance caps on downside protection ETFs don't stay the same from year to year, but fluctuate based on interest rates and market volatility – the factors that influence the price of the options that underlie the ETFs' investment strategy. If rates decline, performance caps tend to decline as well, leaving even less equity participation than the relatively small amount currently available.

In practice, then, a downside protection ETF offers less 'market participation' than an either/or proposition: Either the market declines below the performance floor, triggering downside protection, or it exceeds the cap, limiting total return. Only rarely does the ETF's performance equal the market itself.

Additionally, when the market does exceed the cap, it usually does so significantly. Over the last 100 years of rolling 12-month returns, the average positive return was 18%. On a long-term basis, that's simply far too much upside to give up in exchange for the protection against the relatively fewer negative years – 71% of rolling 12-month periods were positive, versus 29% that were negative. Missing out on the market's best years to avoid the relatively few bad ones more or less guarantees a mediocre overall return and makes it harder for investors to achieve their goals over the long term.

So while the advertised value proposition of downside protection of ETFs is centered around equity exposure – both shielding against volatility and allowing some upside participation – they're hardly a replacement for actual equity exposure in a portfolio. The outcomes are extremely limited compared to equities, both on the upside and downside. And for those who say to that, "Well, that's the point", it's worth remembering that there are assets (like bonds) that already feature less risk and lower returns than equity, without the added expense and complexity of an option-based ETF.

"Defined Outcome" ETFs Are Less Defined Than Treasuries

While downside protection ETFs may not make sense as replacements for equities, they can be more appropriately compared to other assets that also offer protection against loss. Other assets – such as cash in an FDIC-insured bank account, CDs, and Treasury bills – are similarly guaranteed against loss. So what sets downside protection ETFs apart from those assets, which don't have the complexity or fees associated with the ETF products?

The sales pitch for downside protection ETFs is that they provide more upside potential than cash, CDs, or Treasuries, with a similar guarantee of protection. And that is true to a point: With performance caps currently around 6.5% net of fees, downside protection ETFs do offer the potential for higher returns than any of those safe assets, with the added bonus that gains will be 1) deferred until the ETF is sold, and 2) taxed at capital gains rates.

However, there's also a fair chance that a downside protection ETF could return less than those assets. These ETFs bottom out at a 0% return (or, more accurately, –0.5% to –0.8% net of expenses), whereas cash, CDs, and Treasuries guarantee both principal and income. For instance, buying a one-year Treasury today (as of September 2025) would guarantee a return of 3.8%, while a downside protection ETF could return 6.5%, –0.5%, or anywhere in between. If the point of the downside protection ETF – or as they're also commonly marketed, "defined outcome" ETFs – is to have some certainty of outcome, why not use a Treasury where the outcome is actually guaranteed?

If the appeal of downside protection ETFs is that they offer more upside than bonds with similar protection against loss, then the key question is: How likely are they to outperform the one-year Treasury? Using historical stock market data from 1925 to the present based on Robert Shiller's market research, we can come up with a simple estimate: Over 100 years of rolling 12-month return periods, downside protection ETFs would have outperformed the current 3.9% one-year Treasury rate 64% of the time and underperformed in 36%. In other words, about two-thirds of the time, owning a downside protection ETF would have beaten owning a one-year Treasury (which is also the same as saying that owning the S&P 500 as a whole beats owning a one-year Treasury two-thirds of the time).

When looking at a single one-year period, the choice of whether to use a Treasury bond (which has the highest yield of the other similarly guaranteed assets) or a downside protection ETF comes down to whether the ETF's higher potential upside (again, about 6.5% net of fees versus 3.9% for the Treasury) is worth the approximately one-in-three chance that it will underperform the Treasury. In that context, many investors might rather take the guaranteed return over the extra return upside – again, since the whole selling point of the ETF is to provide certainty of outcome rather than the highest expected return.

It's definitely true that investing is not for the faint of heart, and holding on through market volatility can be a major psychological challenge (especially for investors approaching or at retirement age, who are often more concerned with preserving the savings they've built up than growing those funds further). A balanced mix of equities and bonds can dampen this volatility, but it can't eliminate the possibility of loss entirely. That's what makes the sales pitch for downside protection ETFs so compelling; they promise nominal equity exposure with none of the downside.

But the reality is that there's no free lunch in investing. Upside potential always comes with the risk of loss, and reducing downside inevitably involves sacrificing upside. There's no product that can eliminate downside risk without losing much of the upside potential that makes equities a core component of an investment portfolio, and downside protection ETFs are no exception.

The bottom line is that while downside protection ETFs may feel emotionally satisfying to risk-averse investors, in reality, they offer little (if any) more protection than traditional diversifiers like bonds – and they often add more cost and complexity. For advisors, a disciplined portfolio management process (with an emphasis on keeping clients aware of the benefits of staying invested through volatility) can help clients avoid shortsightedly focusing on avoiding near-term losses, keeping them focused on what will help them better achieve their long-term goals!

Leave a Reply