Executive Summary

When deciding on the optimal age to claim Social Security benefits, conventional wisdom – backed by much of the academic research – often favors delaying benefits until age 70. This conclusion is rooted in models that rely on expected value: the assumption that the 'best' decision is the one that maximizes lifetime benefits in dollar terms. To create these models, researchers often use a very low (or even 0%) real discount rate, under the logic that the 'guaranteed' nature of Social Security payments makes them fundamentally different from riskier assets like stocks and bonds. The analysis, therefore, treats future Social Security benefits as nearly (or exactly) equivalent to those received today, which usually favors delaying because doing so results in a higher monthly benefit – and for those who live long enough to reach the breakeven point – a higher total benefit as well.

However, the assumptions used in traditional Social Security research have significant flaws. By focusing exclusively on expected value, they ignore the important concept of expected utility – that is, the value individuals place on outcomes based on satisfaction (or dissatisfaction) those outcomes provide. Although it's easier to assume that every dollar is worth the same regardless of when and under what circumstances it's received, the reality is that preferences vary greatly between individuals. In other words, the practice of using a 0% discount rate – on the basis that Social Security is a 'risk-free' income stream – fails to reflect both the opportunity cost of delaying benefits and the full array of risks associated with that decision.

A more practical framework begins with the expected real return of the portfolio used to bridge the delay – typically around 4%–5% for a balanced 60/40 allocation. Unless a retiree has specifically earmarked more conservative assets, such as a bond or a TIPS ladder, it's realistic to assume that delayed benefits will be funded by withdrawals from the overall portfolio – meaning that the 'cost' of delayed filing is the growth foregone on the assets withdrawn to replace Social Security income.

From there, the portfolio's real return can be adjusted to account for a wide range of risks unique to the retiree. These include mortality risk (dying before breakeven), sequence of returns risk (amplified by higher early withdrawals when delaying), policy risk (future benefit cuts or tax changes), regret risk (emotional reactions if the 'wrong' decision is revealed in hindsight), and health span risk (spending when retirees can enjoy it most). Behavioral considerations also matter: many retirees spend Social Security income more readily than portfolio withdrawals, which means delaying can increase the risk of underspending – particularly in the early years of retirement.

The resulting 'discount rate' for filing age analysis is therefore highly unique to an individual or couple. Retirees with modest portfolios, health concerns, or a propensity to underspend may see effective discount rates of 6%–8% or more, which shifts the decision strongly towards early filing. Conversely, retirees with substantial resources who are less vulnerable to policy or sequence of returns risks may still benefit from delaying until age 70.

The key point is that the default 0% discount rate used in most Social Security research is not just a benign simplification. It biases conclusions toward delayed filing. In reality, each retiree's situation involves a complex mix of behavioral, financial, and institutional risks that require a personalized assessment. By acknowledging these factors and adjusting discount rates accordingly, advisors can offer more balanced, client-specific guidance – often revealing that early claiming may be a rational and preferable choice, not a mistake as traditional expected value-based analyses may indicate!

When it comes to Social Security claiming strategies, there's a very large segment of both practitioners and researchers who have proclaimed that 'waiting until 70' is (almost) always the best route for Americans. There are caveats, of course – such as claiming earlier for a terminally ill individual or considering an alternative claiming age when spousal benefits are factored into the decision – but in many circles, the idea that the higher-earning spouse ought to delay until age 70 is almost treated as a commandment.

While there's substantial research that supports this point, perhaps less appreciated is how controversial some of the key assumptions underlying these analyses are (or at least, how controversial they ought to be!). Looking at the work of researchers like Michael Finke, David Blanchett, William Reichenstein, Laurence Kotlikoff, and Wade Pfau, three notable methodological consistencies stand out that drive the general conclusion to delay until age 70:

- Using an 'expected value' framework

- Using 0% (or very low) discount rates

- Addressing mortality risk by incorporating mortality into future benefit calculations

It's important to emphasize that these researchers are not all identical in their views. For instance, Michael Finke takes a hard line on the use of a 0% (real) discount rate, arguing that "[u]sing a discount rate that incorporates a risk premium is not appropriate for guaranteed future Social Security cash flows." By contrast, Wade Pfau acknowledges that discount rates ought to vary between individuals and that someone with a 6% discount rate might come to different conclusions. Nonetheless, these commonalities exist throughout most of the Social Security claiming research, and, not surprisingly, this would explain why so much of this research arrives at identical conclusions: delay until age 70.

Not everyone agrees with these assumptions. Within the financial advisory industry, for instance, Michael Kitces has argued that the discount rate should reflect the overall portfolio rate of return (i.e., not 0%!). While this might seem like a technical point of disagreement, the implications are actually rather profound. According to a recent CFA Institute study, the average real return for a 60/40 portfolio in the US was 4.89% from 1901 to 2022.

Yet, many research papers use a 0% discount rate for their main analysis and 'stress test' their results with real returns around 2%, then conclude that the results are 'robust' to stress testing. However, 'stress testing' at a 2% real return is still almost three percentage points below actual historical real returns for a 60/40 portfolio. So, if Michael Kitces's view is right, these analyses aren't even close to discounting at the right rates.

But before we get too far down that rabbit hole, it's worth stepping back to consider an even more fundamental issue: Why are these analyses so heavily focused on expected values when expected utility has been the dominant behavioral model for over 80 years?

Expected Value Theory Vs Expected Utility Theory

According to expected value theory, rational actors always maximize monetary expected value. For instance, if given the choice between $20 and a 25% chance to win $100, expected value theory would hold that it is irrational to choose the guaranteed $20 when the expected value of the risky wager is $25 ($100 × 25% chance to win).

However, we know that expected value does a poor job of representing how actual humans behave. Many people do value certainty and are willing to take a guaranteed $20 over a 25% chance to win $100. Expected utility theory – originally developed by Daniel Bernoulli in 1738 and refined later by John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern in 1944 – allows us to acknowledge that most people don't just value things in monetary terms. Instead, they value particular outcomes based on their own subjective utility – or perhaps their personal satisfaction (or dissatisfaction) tied to different experiences.

One common example of this is a (generally) non-linear relationship between utility and money. If someone earning $10k per year gets a surprise $1k bonus, their satisfaction will likely be far greater than that of someone earning $500k per year who receives the same bonus. While most people aren't going to complain about more money, the marginal value of a dollar tends to decrease when someone has more money – this is what economists often refer to as diminishing marginal utility.

Importantly, there are all sorts of layers of complexity we can add to this, such as mental accounting, framing effects, and how reference points shift over time. Someone may have quirky relationships between money and utility (e.g., a business owner might psychologically celebrate going from $999,999 to $1,000,000 in revenue more than they celebrated going from $999,998 to $999,999). The key point is that utility is subjective and is not just about wealth levels; it allows us to examine a much richer landscape of human relationships with money than expected value theory does.

Moreover, there are many ways in which psychological dispositions such as loss aversion can be rational. Our ancestors who were attentive to rustling in the grass – even if it often turned out to be nothing – were more likely to survive than those who weren't. Although this meant reacting to many 'false positives' and expending some time and effort ensuring there was no threat, a small investment of energy was well spent to avoid disaster.

This lens helps explain why behaviors like buying insurance aren't necessarily irrational. On an expected value basis, insurance is always a losing bet: premiums are set such that insurance companies can cover expected claims, administrative expenses, and their profit margin. When buying homeowners' insurance, the payment covers more than the actuarial fair value of the risk. That's not 'irrational' though. It acknowledges that it's worth paying a premium when the trade-off is avoiding a potentially catastrophic loss. Nassim Taleb has argued that when a potential outcome involves ruin, the expected value framework is not reliable as no upside benefit can offset the risk of ruin. As he succinctly puts it: "Don't cross a river if it is four feet deep on average."

Which brings us back to the topic of Social Security claiming strategies. It's very interesting that most of the prominent research familiar to many financial advisors relies on expected value calculations and ignores expected utility. To be clear, work on Social Security claiming strategies using expected utility does exist – but it's often buried as more esoteric content in thinly read academic journals, not in the practitioner-oriented outlets (e.g., Journal of Financial Planning or in financial planning media) where advisors encounter the work from folks like Finke, Blanchett, Pfau, Kotlikoff, and Reichenstein.

The greater representation of expected value work likely owes to its simplicity. It's easier to assume a dollar is a dollar than to untangle the complicated web of what money really means to people. It's also more universal: expected value applies equally to everyone, while expected utility acknowledges that the subjective value of a dollar to one person is not going to be the same as it is to another.

But this is, in effect, a classic example of the "streetlight effect" – invoking the meme of a drunkard losing his keys and searching for them under a streetlight. A police officer asks, "Did you lose them here?" He replies, "No, but the light's better here." In other words, it's the tendency to look for answers where they are easiest to find, rather than where the truth is most likely to be.

Which is why it's silly to pretend that a dollar of retirement income at 62 is no different from a dollar of (potential) retirement income at 95. That's simply not the case, and there are a number of reasons why this assumption should give us pause.

The Ignored Risks Of Delaying Claiming

Before diving into the risks, it's important to acknowledge that the potential benefits of delaying claiming are very real. Almost all attention gets focused on Social Security as longevity insurance – delaying Social Security can help maximize the guaranteed, inflation-protected lifetime income portion of a retirement income plan. That's a real benefit that shouldn't be ignored.

Likewise, there are also meaningful risks associated with delaying claiming, and the list isn't brief. At a minimum, they include:

- Mortality risk

- Sequence of returns risk

- Policy risk (e.g., future benefit cuts)

- Opportunity cost (i.e., missed investment growth potential)

- Regret risk

- Health span risk (i.e., spending delayed into years of declining health and diminished ability to enjoy it)

- Spending optionality/flexibility decline

- Underspending risk (due to lower propensities to spend portfolio income)

Mortality Risk

One of the most obvious risks associated with the Social Security claiming decision is mortality risk. Simply put, this is the risk that an individual dies before reaching the point where they would have come out ahead from delaying their claiming.

While it's true that death itself eliminates the need for retirement income, there are still very material financial risks that individuals face. Consider the following example:

Example 1: James is 61 years old and single, and has decided to claim his projected $2,710 monthly benefit early, when he becomes eligible at age 62 next year. He expects inflation to average 3% and his portfolio to earn 8% (roughly a 4.85% real return after accounting for the cross product of inflation and nominal returns).

James does not plan to spend his Social Security benefit, since his pension already covers his current spending needs, so he invests every check into a stand-alone taxable brokerage account.

Unfortunately, James passes away at age 70 – with $398,310 accumulated from his Social Security benefits.

In the example above, James claims at age 62 and dies at age 70, leaving behind nearly $400k from his Social Security benefits. Had he waited until 70, that money simply would not have existed.

We simply cannot ignore the mortality risk associated with the outcome here. Even with different assumptions about returns, benefit levels, or spending, the risk of dying before break-even leaves significant value on the table.

Furthermore, if James had delayed claiming until 70, it's hard to imagine him finding out his prognosis without some regret that he hadn't claimed sooner. Even if he doesn't end up spending this money, it's still money that could go to people or organizations that he cares about. And while this scenario was also set up to illustrate value at risk when considering potential portfolio growth, even if James had been spending the money along the way, that income could have meant extra dollars he was more willing to spend and enjoy retirement (versus spending from portfolio assets that many retirees have a lower propensity to do).

And while it is absolutely true that we need to weigh this against hypothetical longevity protection that delaying Social Security could provide, I do have a hunch that people who delay and pass early (or receive a prognosis of passing early) experience stronger regret than those who claim early and live a long time. I'm only speculating, and I'd love to see some empirical data speak to that, but a 68-year-old receiving a terminal diagnosis and kicking themselves for not claiming Social Security earlier just seems more realistic to me than a 92-year-old who claimed at age 62, feeling regret that their Social Security check could have been a bit larger if they had claimed at 70.

But the key point here is that we shouldn't focus just on longevity risk – we have to consider mortality risk, too.

On that note, I'm sure the authors I referenced above would object, "But Derek, we do account for mortality risk!" And, in a technical sense, this is true, but they do it in an expected value framework (not an expected utility framework). I don't think this approach translates to real life well at all.

The way mortality risk is handled in most Social Security claiming research is to simply apply a mortality adjustment to future benefits. Essentially, researchers look at actuarial tables and adjust benefits for the likelihood that someone will actually be alive at that time. But simply looking at 'average' values amounts to looking at a reality that no one will ever face. People only have one life to live. We can't sit down with a 68-year-old individual who delayed claiming and is now lying on their deathbed, and say, "Well, on average, you actually did maximize your Social Security benefits by delaying." None of us experiences averages. We don't receive 'mortality-adjusted' Social Security benefits. We either get our checks or we don't.

Taleb's warning applies here: don't cross a river that is "on average" four feet deep. As we cross the "mortality risk" river, the methods most commonly used in academic Social Security claiming research essentially ask us to focus on the average depth of four feet. They're saying, "Come on in, the water is fine!" – while ignoring the fact that it can be deep and treacherous in the early years of retirement, even if it averages out to four feet once we wade into the ankle-deep shallows in the later years.

Sequence Of Returns Risk

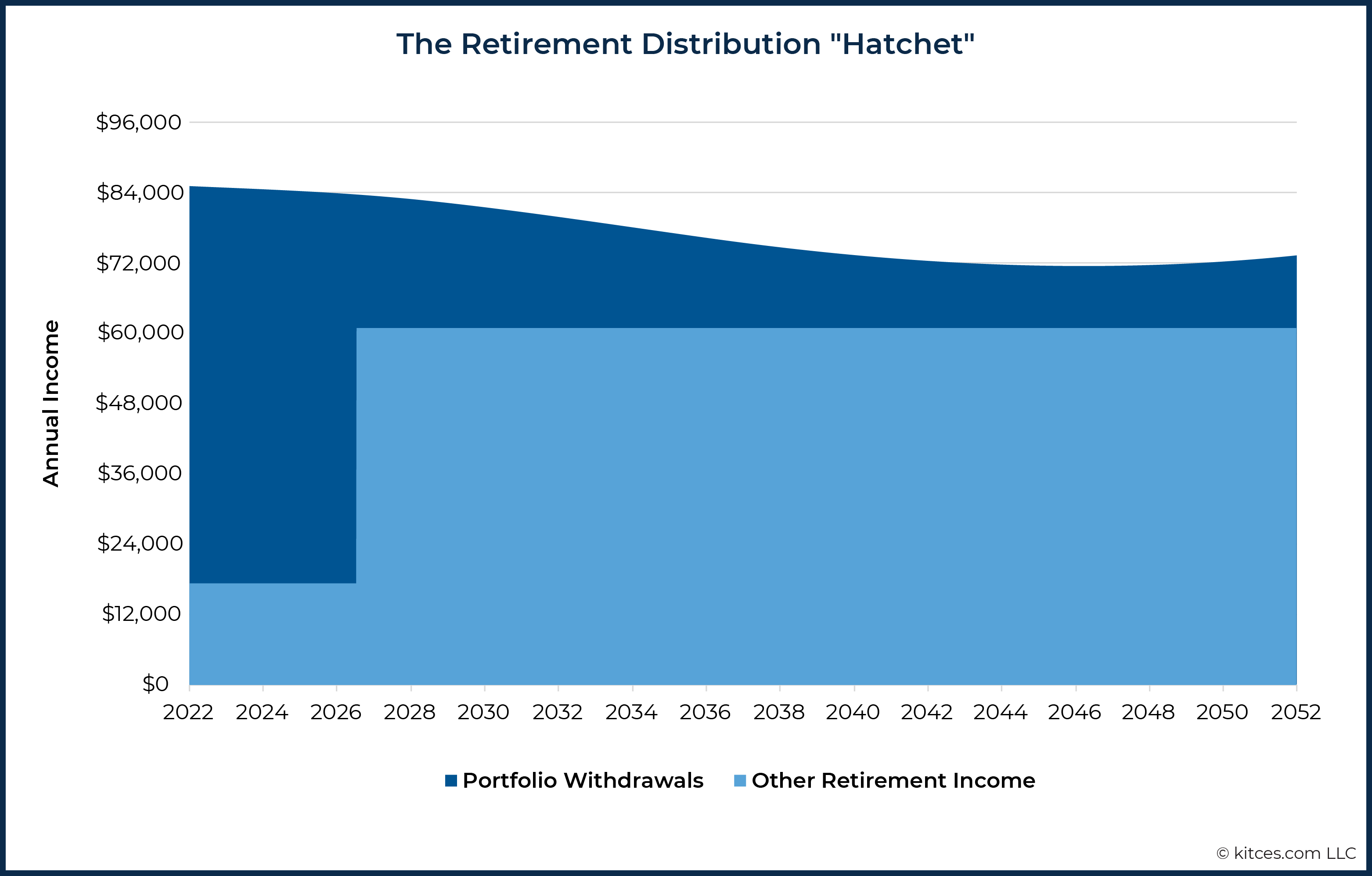

The retirement distribution hatchet – referring to the 'shape' that often applies to retirement portfolio distributions – greatly enhances sequence of returns risk.

Most of the research done on sequence of returns risk assumes a flat (in real terms) sequence of distributions across retirement. In other words, the exact same amount is distributed from a retirement portfolio each year, adjusting only for inflation.

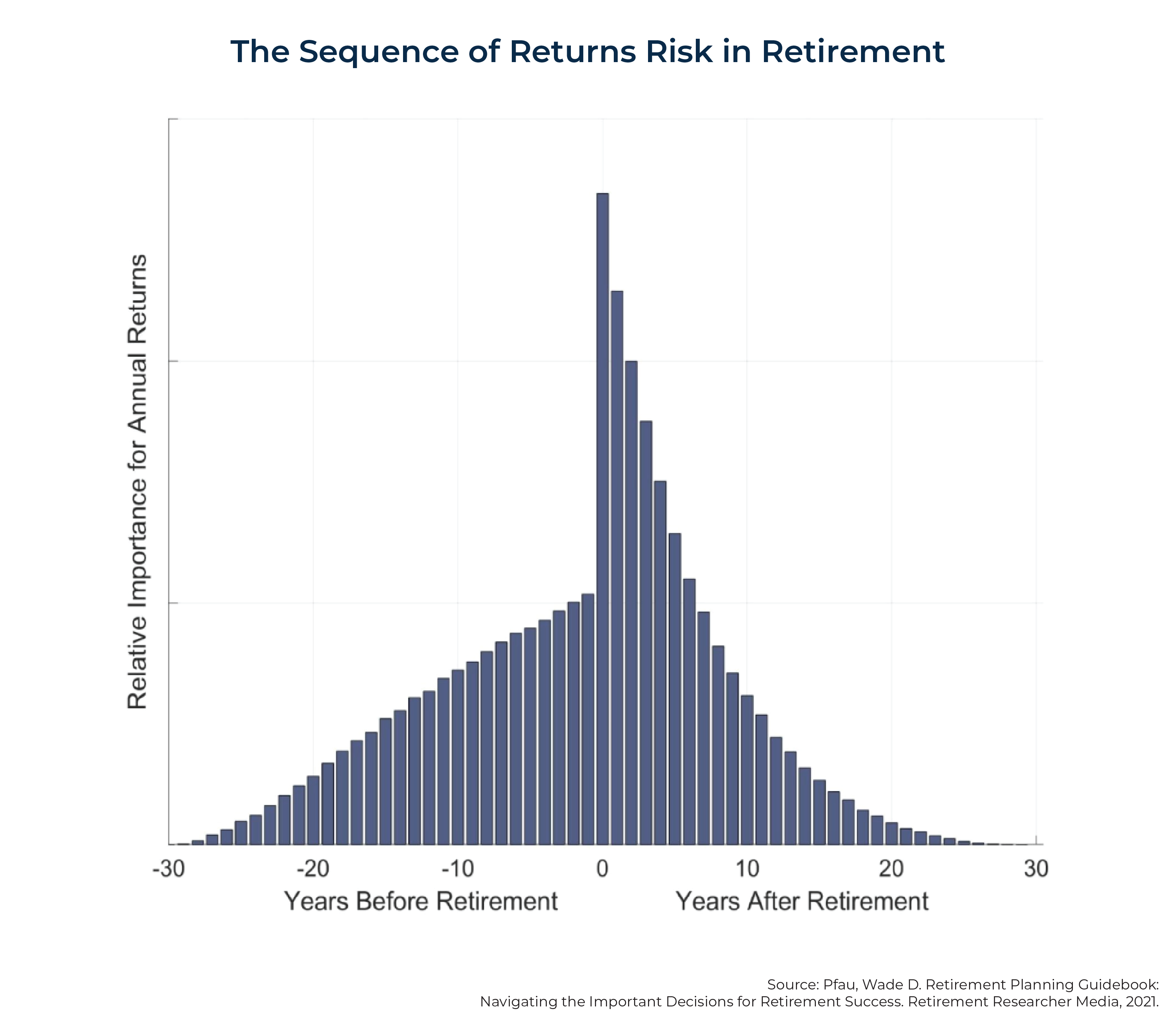

Even under this assumption, sequence of returns risk still shows up clearly, as in this often-cited chart from Wade Pfau:

As the chart above shows, sequence of returns risk is meaningful, and it is highest for about the first seven years of retirement. However, this model assumes that the individual pulls from their portfolio at the same rate in the first year of retirement as in their 20th year of retirement. In reality, for those who delay claiming Social Security and need to draw more heavily on their portfolio initially, this exacerbates the sequence of returns risk.

For some Americans, delaying Social Security benefits could actually mean drawing from their portfolio at a rate four times, five times, or more than they would later in retirement. While I'm not aware of any research that has actually quantified this risk in the same manner as Pfau has for constant inflation-adjusted distributions, it's not hard to understand why this actually elevates this risk dramatically.

For retirees who hit a very poor sequence of returns, delaying benefits may leave them flirting with portfolio 'ruin' (at least in a practical sense).

Case Study: The Impact Of Claiming Age On Sequence Risk

For example, consider Mike, age 62. Mike is considering when to claim Social Security. He is single, has a $500k IRA portfolio allocated 60/40, and is eligible for a monthly Social Security benefit of $2,200 beginning at 62. He wants to compare how both his retirement income and investment portfolio would look when stress-tested through historical markets, claiming at age 62 versus 70, while using a risk-based guardrails approach.

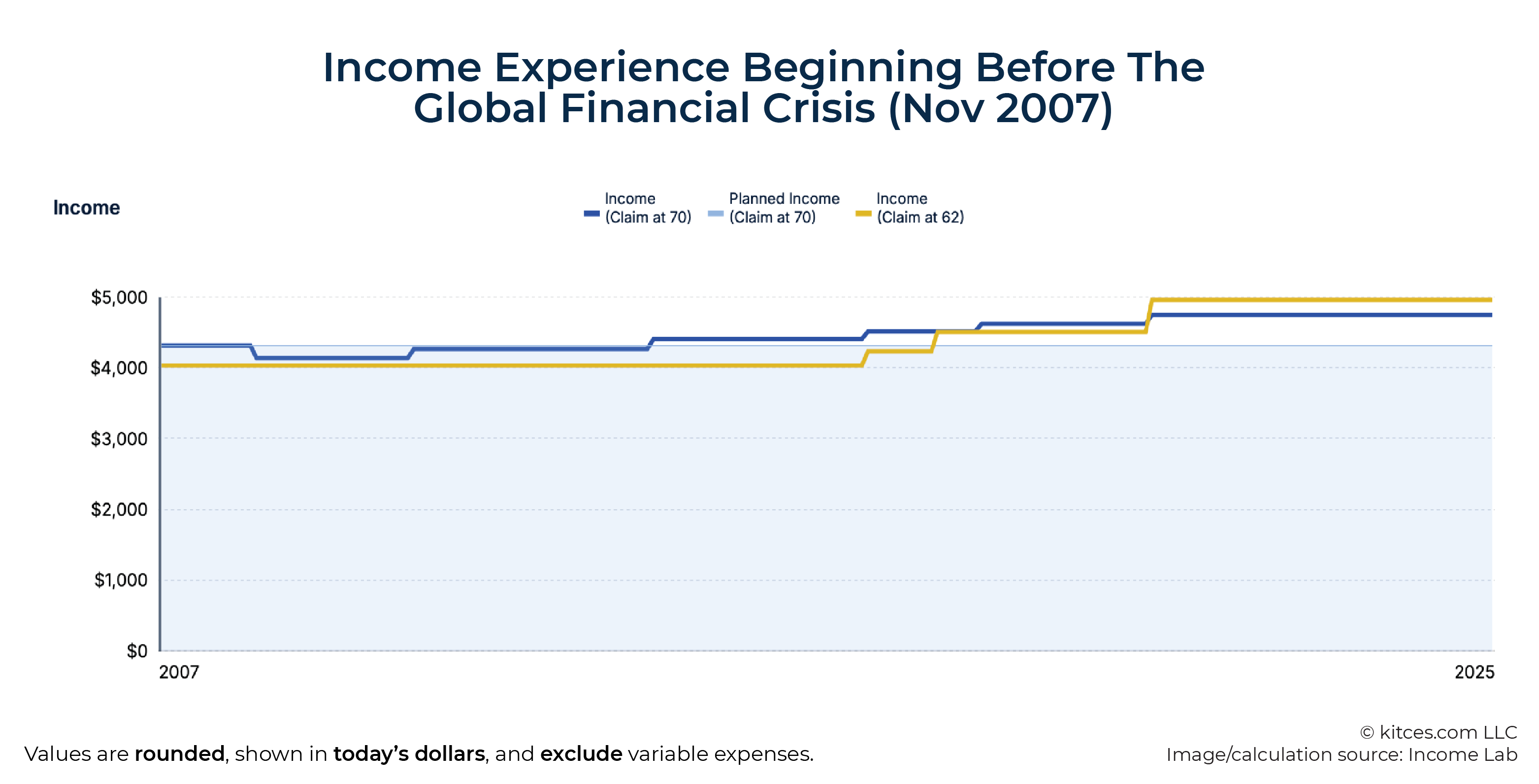

Perhaps surprisingly, Mike's spending potential ends up being fairly similar regardless of whether he claims Social Security at 62 or 70. If we assume Mike retired just before the Global Financial Crisis beginning in 2007, here is what his spending could have looked like using a risk-based guardrails approach:

As the graphic above suggests, Mike would have started out with slightly lower spending potential by claiming at age 62 compared to age 70 ($4,040/month versus $4,320/month). However, turning on Social Security early reduced his sequence of returns risk – he never needed to cut back his spending, whereas a cut was required when delaying Social Security through the financial crisis.

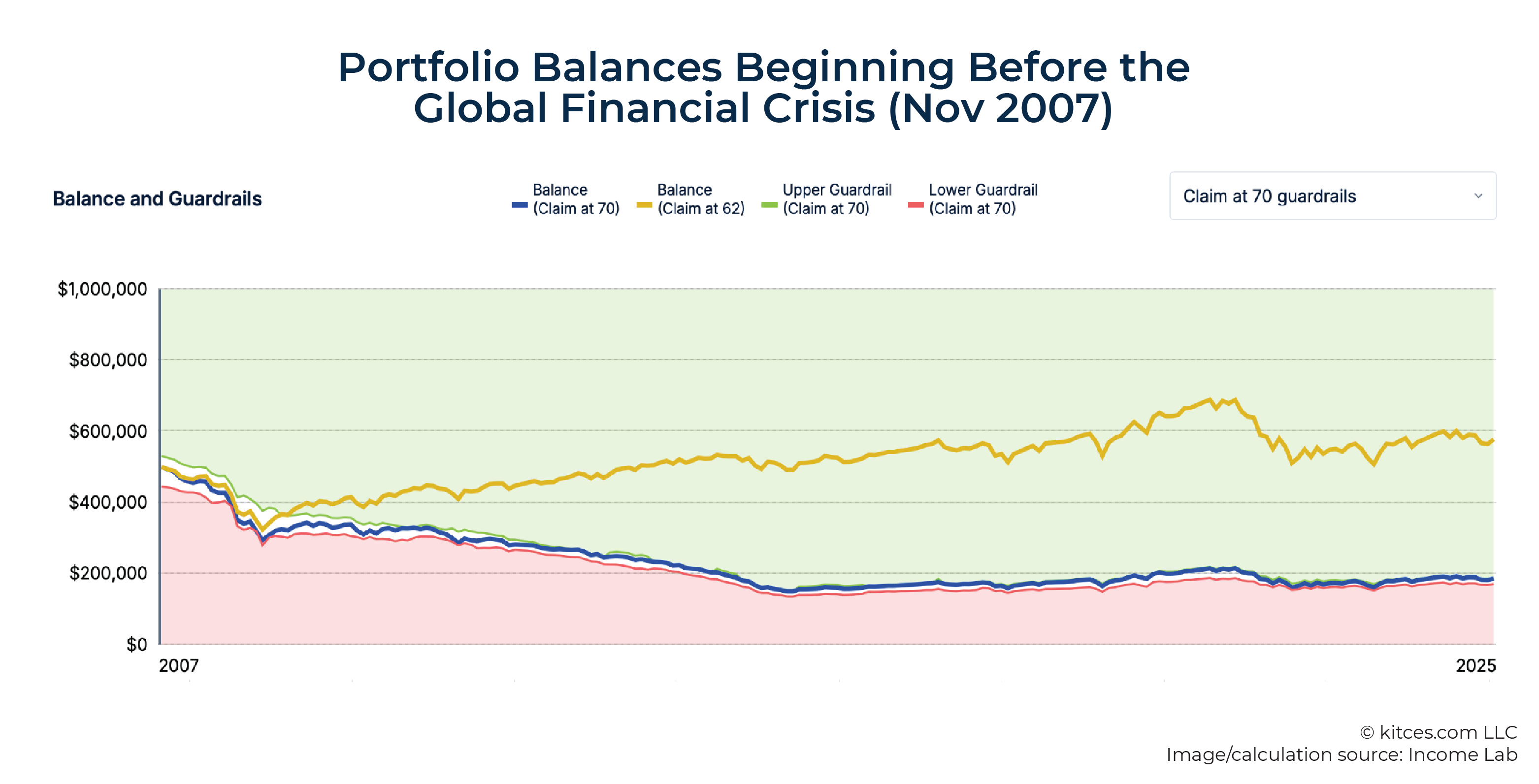

Furthermore, the portfolio erosion that occurred during the Global Financial Crisis had longer-term implications for Mike as well, including the fact that Mike ultimately could have ended up with even higher spending potential later in life when claiming at age 62. This result is due to major differences in portfolio balances stemming from the decision to claim at age 62 versus 70. Here is how his portfolio fared (in nominal dollars) through these two different scenarios:

While both scenarios felt the impacts of the Global Financial Crisis, the divergence beyond this point was huge. 18 years later, Mike would have a portfolio of about $578k when claiming at age 62 versus $171k when claiming at age 70. This is a difference of over $400k and is certainly nothing to scoff at. These are extra reserves that Mike could spend enriching his retirement by doing things that are important to him or supporting the causes and people he cares about. Additionally, this could also serve as an extra reserve to help address risks such as long-term care expenses.

Of course, there are some ways to mitigate sequence of returns risk when delaying Social Security. One option is to preserve flexibility by turning on their benefits if needed (and even retroactively claiming up to six months' worth of benefits). Retirees could choose to delay Social Security with a cautious 'wait-and-see' approach – taking advantage of six-month 'reversible' delays. Unlike mortality risk, which is only minimally reduced by retroactive claiming, this is a meaningful strategy for navigating sequence of returns risk.

The key point here is that there is a legitimate sequence of returns risk that is often overlooked in Social Security claiming strategies. While mortality adjustments are common (with significant limitations as noted above), at least those risks tend to be captured in the common expected value framework – unlike sequence of returns risk, which is often neglected entirely.

Policy Risk

Many advisors and researchers tend to be dismissive of the risk of Social Security benefit cuts for those in or near retirement – perhaps justifiably, since such cuts would be politically unpopular and most historical proposals have grandfathered current Social Security recipients. Still, this risk weighs heavily on the minds of Americans.

A 2025 AARP report found that only 36% of Americans were confident in Social Security's future. Much of this concern stems from fears about the depletion of the Social Security trust fund, currently projected to occur in 2033. The report also noted that some Americans misunderstand what depletion of the trust fund means (e.g., a belief that when the trust fund is depleted, all benefits would be gone rather than just reduced). But the reality is that if nothing changes, benefit cuts are projected.

Policy changes are hard to forecast, and retirees may justifiably worry about other types of risk as well. For instance, changes in how Social Security is taxed could reduce net benefits even if gross payments remain the same. Other potential adjustments – such as targeted reductions based on income or wealth, or adjustments in how inflation is calculated (e.g., the Obama administration's proposal to adopt chained CPI) – could effectively reduce future benefits in less direct ways.

The key point here is that there is legitimate policy risk associated with delaying Social Security. We shouldn't sweep it under the rug, although that's effectively what happens when researchers use a 0% discount rate and assume that one dollar of Social Security income today is equivalent to a dollar at age 90, without accounting for the possibility of future cuts.

Opportunity Cost

While most Social Security claiming analyses share common assumptions that are widely accepted, opportunity cost is one area where there is some disagreement – at least among some prominent voices in the industry. For example, here's an exchange between Bill Meyer and Michael Kitces that highlights the core of the disagreement around opportunity cost:

On one hand, many academics and researchers argue that the correct discount rate should reflect the risk profile of Social Security itself. They view Social Security as inflation-adjusted, risk-free, and guaranteed for life; therefore, they often suggest a simple 0% discount rate or perhaps a rate tied to the current TIPS curve. Notably, this approach has even driven discount rates negative in recent years, resulting in a dollar of Social Security income in the future being worth more than a dollar of Social Security income today. Generally, within this perspective, when higher discount rates are used to stress test results, they often stop at around 2% real returns, still far below the ~5% real returns historically earned by a 60/40 portfolio (as cited in the CFA report mentioned earlier). Michael Finke captured this view when he said, "Using a discount rate that incorporates a risk premium is not appropriate for guaranteed future Social Security cash flows."

On the other hand, critics argue from a practical perspective. Most retirees (and their advisors) set an overall target portfolio allocation – commonly 60/40 – independent from how they claim Social Security. As a result, if additional withdrawals come from that portfolio to cover income before Social Security begins, then the relevant opportunity cost is the expected returns of that 60/40 portfolio (historically about 4.89% real returns).

Proponents of the 0% discount rate often counter that funds withdrawn from a portfolio in lieu of delayed Social Security benefits should come from a retiree's bond allocation. This effectively increases equity exposure over time as bonds are spent down.

While this is rarely done in practice, it's still worth noting that even then, TIPS may not be the right benchmark unless the retiree's bond allocation (or at least the portion being depleted) is made up entirely of TIPS. In practice, many retirees hold bonds with some risk premium. More fundamentally, this strategy comes with some serious issues. Consider a retiree who hits a poor sequence of returns, which, as we saw in the example above, could deplete 80% or more of their portfolio. At some point, they'd need to start selling stocks just to make up for the shortfall. Moreover, this only further exacerbates the sequence of returns risk. What started out as a 60% stock portfolio could be anywhere from a 60% to a 100% stock portfolio for someone heading into a downturn.

So, what's the 'right' answer? It depends on how a retiree plans to source the income that will fund delaying Social Security. If the retiree truly plans to draw entirely from TIPS, then a TIPS curve may be the right discount rate to apply. However, this isn't a very common strategy. So, in practice, if someone draws from a 60/40 portfolio, the expected return on the actual funds being spent down should be used instead.

"But Derek, isn't this ignoring differences in risk?" Yes, in a way – while this is an apples-to-oranges comparison, I think that's still the best we can do here. Notably, this isn't a unique challenge to Social Security claiming. In corporate finance, companies evaluating mutually exclusive projects with different risk profiles face the same challenge. In theory, risk-adjusted discount rates could be applied; in practice, though, the company typically chooses between one of two mutually exclusive opportunities (identical to funding retirement from Social Security or from a portfolio). The opportunity cost is the return of the forgone option.

Long story short, for real-world comparisons, we have to compare our real-world options. That means a good baseline is to start with the expected returns of the actual portfolio funds that would otherwise be spent down. Yes, there's some investment risk in hoping for future growth on a risky portfolio, but the industry discussion has been overly focused on this one type of risk. We can't just look at things in a vacuum and say, "Investment risk is lower," without also acknowledging how mortality risk, sequence of returns risk, policy risk, and more all affect the decision. Many of these risks should truly be additive in a holistic risk assessment. Once we take that big picture view, it's not unreasonable to conclude that delaying claiming Social Security is the riskier decision, and, if we're going to use a discount rate as part of an expected value calculation, it's entirely possible that the discount rate ought to be higher than the expected rate of return on a portfolio, all things considered!

Regret Risk

The purely analytical approach so commonly used to evaluate Social Security claiming strategies misunderstands how people actually perceive and experience risk. If we apply Peter Sandman's work on risk communication, what we call "risk" here (i.e., the investment profile of a portfolio versus Social Security benefits) would only be part of the equation. In Sandman's framework, Risk = Hazard + Outrage, where "Hazard" represents the objective, quantifiable danger (e.g., Social Security benefits cut by 21%), and "Outrage" captures the psychological factors that make certain risks feel unbearable regardless of their statistical probability. Think of how different people respond to turbulence on a commercial plane versus driving on a highway – despite the latter actually being far riskier.

From this perspective, the hazard might suggest that delaying Social Security is actuarially advantageous, but the outrage factors – whether risks feel voluntary or coerced, fair or unfair, morally irrelevant or morally relevant, controllable or uncontrollable, individual or institutional – fundamentally shape how people experience the risks of delaying benefits.

The outrage inherent in Social Security claiming decisions manifests in ways that portfolio management decisions simply cannot replicate. Consider the visceral difference between two scenarios: receiving a terminal diagnosis at age 69 after delaying benefits (having "paid in all these years and got nothing in return") versus reaching age 95 and feeling mild disappointment (if any) that benefits could have been slightly higher by delaying.

This asymmetry of regret highlights some unique psychological aspects of Social Security. To many, it represents a social contract between citizen and government, paid into through decades of mandatory contributions. When someone who delayed claiming receives a terminal diagnosis or when politicians alter benefit rules, the outrage factors can stack up: the loss feels involuntary (health or Federal policy is beyond control), unfair (they followed expert advice and played by the rules), morally relevant (they upheld their end of the contract), memorable (the health diagnosis or policy change becomes highly emotionally salient), and dreaded (decades of contributions with no/lower return feel wasted). These factors transform what might be a mathematically equivalent loss into something far more psychologically devastating. Moreover, if they fund their delay by spending down their portfolio, the regret comes with the added pain of watching their hard-earned nest egg deplete more than necessary.

This psychological reality grows more complex when we consider the institutional risks that make Social Security fundamentally different from portfolio assets. Unlike market volatility – which might feel natural, familiar, and part of the accepted investment landscape – political benefit cuts represent institutional betrayal. The possibility that policymakers could reduce benefits after someone has already forgone years of payments to maximize their age-70 benefit triggers what Sandman might call extreme outrage: the outcome is controlled by others (politicians), morally relevant (breaking societal promises), and unfair (changing rules mid-game).

Through this lens, the common assumption that Social Security represents the 'safe' portion of retirement income while portfolios carry the 'risk' may be backward from a psychological perspective. Understanding these outrage factors – and how they interact with our mental accounting tendencies to segregate Social Security from other assets – helps explain why the decision to delay carries a weight that no amount of break-even analysis can fully capture.

Health Span Risk

In "Die With Zero," Bill Perkins refers to "health span" as a crucial concept that fundamentally challenges how we think about saving and spending throughout our lives. Unlike lifespan, which simply measures how long we live, health span represents the years we're physically and mentally capable of enjoying life's experiences – from adventure travel and physically demanding activities to even simpler pleasures that require baseline mobility and energy.

Perkins argues that most people tragically miscalculate by saving too much for a future when their declining health span will prevent them from extracting maximum enjoyment from their money, illustrating this with his "time buckets" framework that shows how certain experiences have expiration dates tied to our physical capabilities. He emphasizes that understanding health span should drive financial and life decisions, encouraging readers to front-load meaningful experiences during their peak health years rather than indefinitely deferring gratification until retirement, when their bodies may no longer cooperate with their bucket list dreams.

Health span is particularly relevant to how we think about claiming Social Security benefits. Consider the 'default' 0% discount rate assumption in most Social Security claiming research – according to this view, an extra $10k at age 62 is identical to an extra $10k at 95. However, we know this is not the case.

At age 62, an individual is simply far more capable of using that extra $10k for active experiences. Furthermore, this applies not just to the range of things they could do with the money, but also the lifetime benefit they may receive from the experiences (i.e., the "memory dividends" as Perkins refers to them). Hiking with family up to the top of a mountain, taking an adventurous trip, or jumping in the water with grandkids are experiences that simply can't be replicated at 95. Pretending otherwise ignores reality and is, frankly, absurd.

This also applies to giving. Early retirement is often the phase when spending can be more impactful for those who retirees may care the most about, such as children. Children may be purchasing first homes, starting families, completing education, etc. Consider the difference between giving an extra $50k to a 30-year-old child to help with a down payment on a home, launch a business, or finish professional school debt-free versus giving $300k at age 60 that simply adds to an already-established nest egg. Of course, $300k at age 60 is still a wonderful gift, but it's unlikely to really move the needle much in terms of having an impact on someone's life.

The key point here is that it is perfectly rational to prefer receiving income earlier in life, when health span is greater. Although many retirees want to maintain their health and vitality long into retirement, that's never a guarantee.

Additionally, for many Americans, claiming Social Security frees them up to feel like they can retire. Academics can argue all day about how people ought to treat the concept of retiring and claiming Social Security separately, but the reality is that, behaviorally, people often view Social Security as 'permission' to retire – even when they have already saved enough to do so.

The effective result is that discouraging earlier claiming may also keep people working longer than necessary. And sacrificing one's healthiest years of retirement working when it isn't required may ultimately be a very costly decision.

Spending Optionality

Maintaining spending optionality is a factor in the Social Security claiming process that is greatly overlooked. The concept of 'real options' provides a useful decision-making framework here. Just as a stock option gives the right but not the obligation to purchase a stock, 'real options' in life represent the flexibility to act when opportunities arise – if, when, and how an individual chooses.

Think of real options as doors that are kept open. By maintaining liquidity and avoiding overcommitting resources, the ability to say "yes" when life presents a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity is preserved. A family trip, a chance to give to a person or organization in great need, the ability to help a child with a house down payment – these are all opportunities that may appear unexpectedly and require both available resources and the freedom to act.

While the insurance value of Social Security is great, the reality is that it offers much less spending optionality than a retirement portfolio. You can't ask the Social Security Administration to send five months of benefits in advance to take your daughter to see her favorite musician perform in Paris. Credit cards or loans can provide some flexibility, but people spend differently when debt is required, and meaningful limits apply here, too. For instance, it might take years of Social Security benefits to save up a $50k gift for a down payment on a home, whereas those funds could be available immediately from a portfolio.

In the most extreme cases, trying to maximize Social Security could ultimately mean fully depleting a portfolio as a bridge to get to the point of claiming Social Security, and then having Social Security as one's only source of income for the rest of their life. Conceptually, imagine someone spending $40k per year from their portfolio, fully depleting it in the process, just to reach the point of turning on their $40k Social Security benefit. That lifetime guaranteed income is a valuable benefit, but it comes with effectively zero optionality.

For retirees with no choice but to rely on Social Security, that may be their reality. But for those with some combination of Social Security and portfolio assets, it may be perfectly rational to preserve more portfolio to provide greater optionality, even if that means lower income overall.

This issue is particularly important in heavier market downturn scenarios or for those with modest assets relative to their Social Security income. A decamillionaire will maintain optionality regardless of their claiming decisions, but the same may not be true for a retiree with a $500k nest egg.

Underspending Risk

As alluded to earlier, another real concern with delaying Social Security is that people think about Social Security income differently than portfolio income.

Social Security income is some of the 'easiest' retirement income to spend. In academic terms, people have a higher propensity to spend Social Security than portfolio income. For many, Social Security is almost a forgone conclusion that it will be spent month-to-month. By contrast, spending from a portfolio can feel painful – particularly for those averse to watching their nest egg shrink as they struggle with transitioning from saving mode to spending mode.

This pattern is consistent with research findings. Blanchett and Finke's 2025 study found that "roughly 80% of lifetime income is spent, while only approximately half of wage income and capital income are spent." Their 2024 study also found that "retirees spend twice as much each year in retirement if they hold guaranteed income wealth instead of investment wealth."

In the context of claiming decisions, this means claiming earlier could have a meaningful impact on how much someone is willing to spend (and when they are willing to retire). Encouraging people to delay based on studies that treat a dollar at 95 as identical to a dollar at 62 may inadvertently nudge people toward underspending, particularly between ages 62 and 70.

Interestingly, while Blanchett and Finke's work points to the benefits of using commercial annuities earlier in retirement to increase spending confidence, neither paper makes the case for claiming Social Security earlier to achieve similar behavioral benefits. In fact, they frame delaying Social Security income as beneficial from the behavioral standpoint of increasing spending later in life.

However, this is an overly narrow assessment of the range of possibilities available to retirees. Claiming earlier can unlock the same behavioral benefits of increasing spending while maintaining the optionality provided by portfolio assets, as discussed previously.

This is not to suggest that there aren't valid reasons to delay – there certainly are! But underspending risk is very real, and it may especially affect the kinds of conscientious, diligent savers who often work with advisors. If turning on Social Security earlier gives someone the confidence to retire earlier and/or spend more in their healthiest years, then underspending risk deserves to be treated as a legitimate risk in claiming strategies.

Bringing It All Together

While the list here is certainly not meant to be exhaustive, we have covered an extensive list of risks that are generally neglected when analyzing Social Security claiming decisions.

But… what are we actually supposed to do with all this information?

From an academic perspective, I'm not optimistic that there's any real practical solution to conducting these types of studies in a meaningful way.

Trying to formalize all of these different risks into a single model (even a utility-focused model rather than an expected value-focused model) in a meaningful way is arguably intractable. In a lot of academic work, a simple ('parsimonious') theory or operationalization of a theory is highly valued. There can be benefits to this, for sure, but it often lends itself to being better for answering questions in aggregate rather than guiding individual decision-making.

For instance, the "life-cycle hypothesis" developed by Madigliani and Brumberg in the 1950s states that people prefer to smooth their consumption over their life-cycle, resulting in borrowing and saving in the earlier years of one's life and dissaving in retirement. Aggregate analyses of household behaviors will confirm we do see such behaviors in the real world, but the life-cycle hypothesis isn't very useful for providing guidance for saving or dissaving decisions for individuals.

Michael Kitces and I have shown that the desire for elegant mathematical formalizations can distort the scenarios actually modeled. In our 2017 article in Journal of Retirement, we compare Blanchett et al.'s (2017) earnings curves (based on some nice, elegant functions) to real-world earnings curves from observed Social Security data from Guvenen et al. (2016). The comparison is striking. The full spectrum of earnings curves modeled by Blanchett et al. (2017) fits within only the 50th to 80th percentiles of real-world earnings curves. In other words, reality is messier than overly formalized academic models.

This is very much the case with trying to find one simple solution to discount rates or utility curves. No single 'utility curve' will capture the nuance of the multifaceted types of risk we've discussed. Longevity risk increases the utility of delaying, while mortality risk and other risks reduce it. The ultimate 'utility' derived is also highly path dependent. A retiree who lives past 90 with no benefit cuts may be glad they delayed, while the same retiree could deeply regret that choice if they had received a terminal diagnosis at 68 or if future benefits were cut.

Ironically, this might bring us back to discount rates as a practical way to approximate risks for individuals – although the 'right' rate is almost certainly not 0%!

Let's consider some case studies to see how this plays out.

Case Study: Claiming Early With Limited Assets

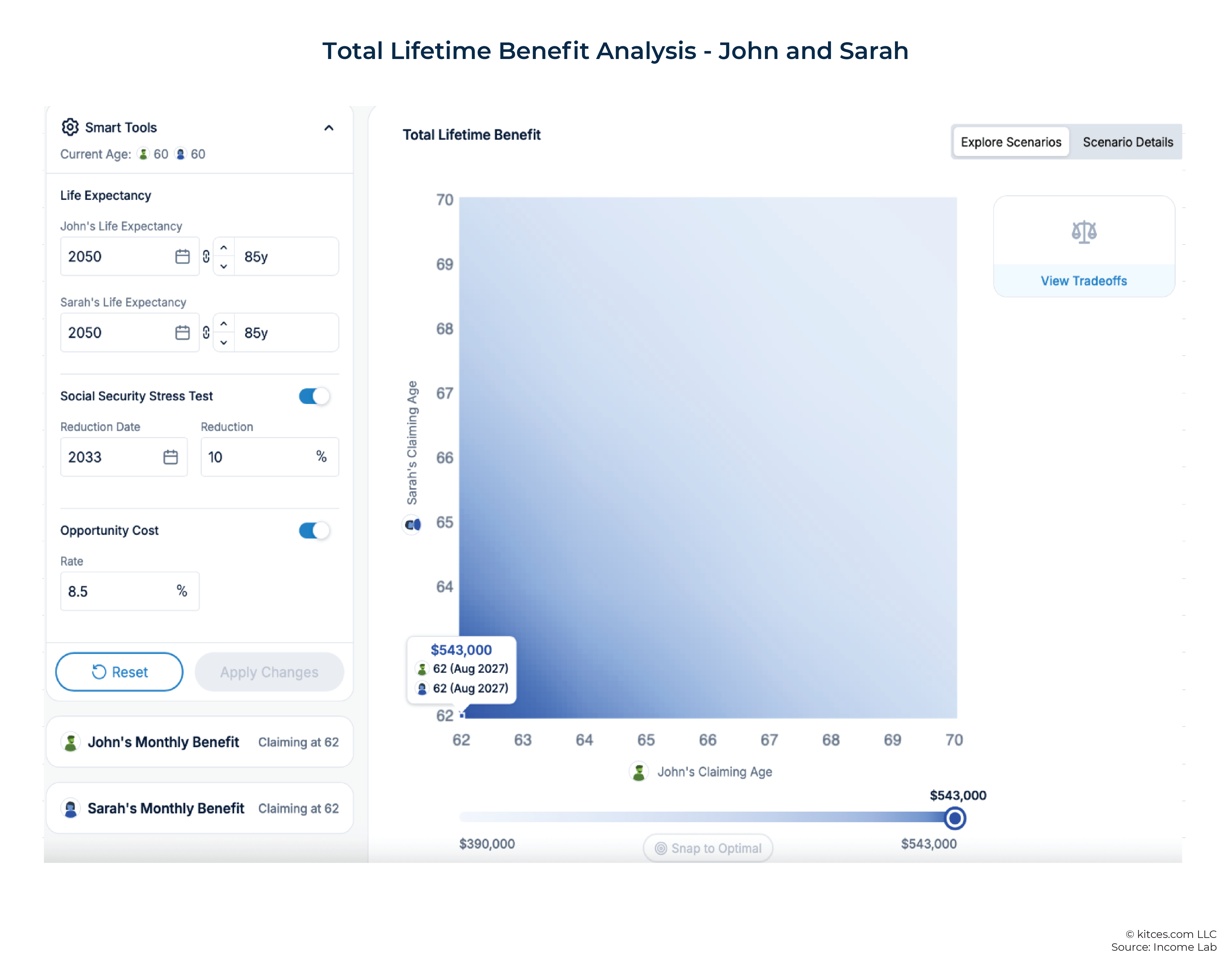

John and Sarah are each 60, eager to retire, but stressed about doing so without claiming Social Security. They fear future benefit cuts (10% or more), worried about dying (their parents all died before age 80), and want to preserve portfolio flexibility for travel and gifts to their children in the next 10 years.

Their $500k portfolio is allocated 60/40, and at age 62, they will be eligible for a combined $5k monthly Social Security benefit. They have a spending goal of $6k per month.

The first factor to consider when setting a discount rate for John and Sarah is the opportunity cost. If they delay claiming Social Security, they will draw funds directly from their retirement portfolio. Moreover, it isn't feasible for them to simply spend down their bond allocation, as they are targeting $60k in annual spending and have only $200k in bonds. Therefore, the most reasonable opportunity cost is the portfolio's expected return – a real return of 4% would be a reasonable baseline (still lower than the ~5% historical return mentioned previously for 60/40 portfolios).

Notably, this is just a baseline. Beyond this, we need to account for client-specific risks and adjust accordingly. The following illustrates how different risks could be layered on when determining an appropriate discount rate:

- Mortality Risk: +2.0% (John and Sarah do not have longevity in their family and are concerned about this)

- Sequence of Returns Risk: +2.0% (their desired $60k annual spending amounts to a 12% withdrawal rate, making them highly sensitive to early downturns)

- Regret Risk: +0.5% (John and Sarah expressed they would feel regret around policy cuts or dying prematurely)

- Health Span Risk: +0.5% (they are inclined to defer spending or even retirement without Social Security income)

- Spending Optionality/Flexibility Decline Risk: +0.5% (delaying Social Security could deplete their retirement nest egg, leaving little flexibility)

- Underspending Risk: +0.5% (John and Sarah's saving background suggests they may spend less without Social Security income to rely on)

- Longevity risk: –1.0% (John and Sarah would benefit from longevity risk protection if they delayed claiming)

Adding these together results in a client-specific discount rate of 8.5% – the 4% real opportunity cost from their portfolio plus another 4.5% after addressing risks that increase or decrease their discount rate.

Finally, one additional factor that can be addressed separately is future benefit reductions. This is easier to model into an analysis, and, in John and Sara's case, we might assume a 10% cut beginning in 2033 when the Social Security trust fund is projected to be depleted.

The end result is summarized in the following chart. This chart plots combinations of claiming ages for both John and Sarah between ages 62 and 70, with darker areas indicating higher lifetime benefits. As is clearly illustrated here, based on the assumed 8.5% discount rate, the advantage for both John and Sarah claiming as soon as possible at age 62.

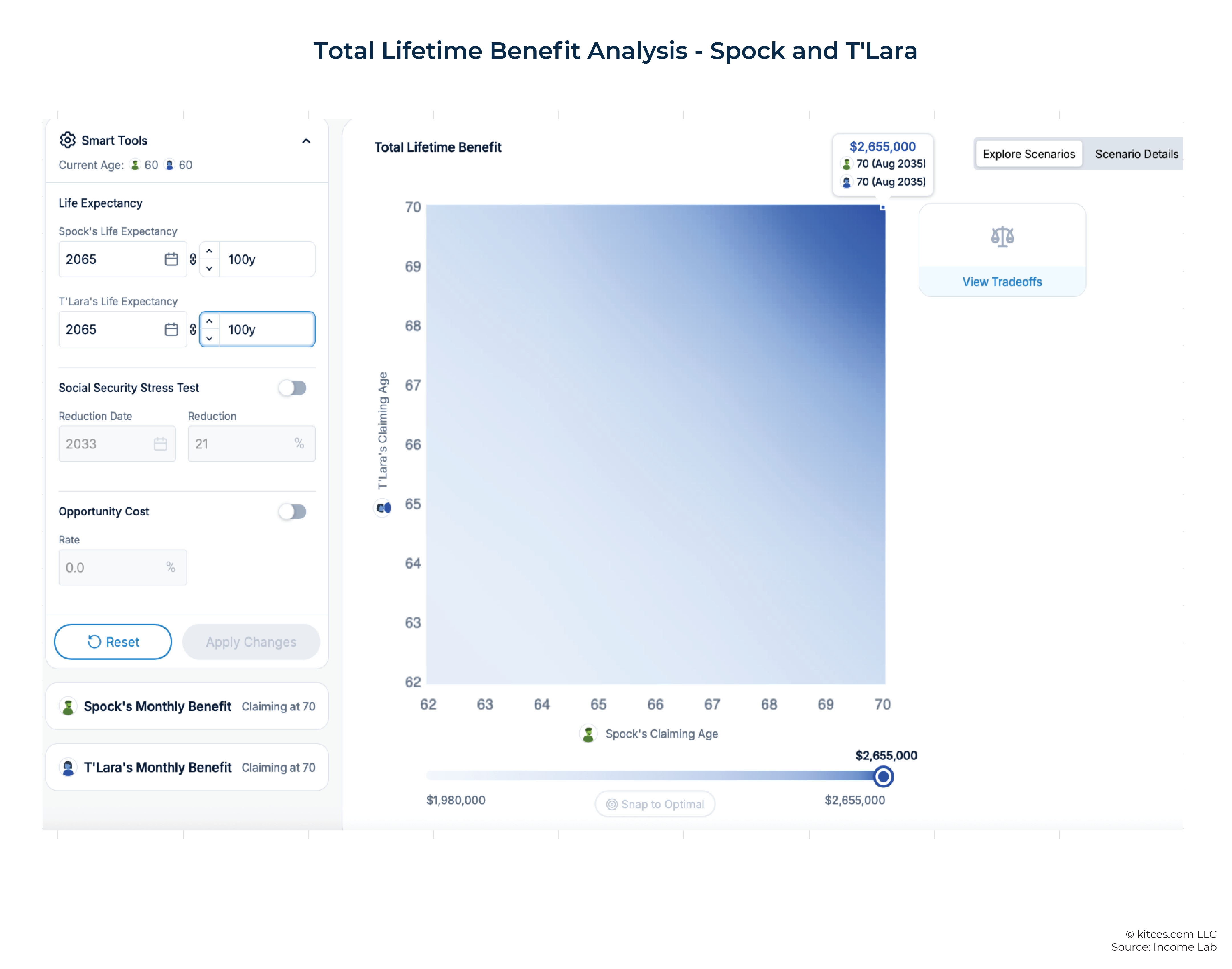

Case Study: Claiming Later With a TIPS Strategy

While John and Sarah's situation highlights how limited assets, health concerns, and spending goals can tilt the scales toward early claiming, it's just as important to see how a very different profile and set of assumptions could lead us in a very different direction.

Meet Spock and T'Lara. They are both 60 and want to retire as soon as possible. But unlike John and Sarah, they are 100% indifferent to the source of their retirement income. As Spock puts it, "To suggest that a dollar from Social Security holds greater utility than a dollar from a brokerage account is illogical – unless, of course, the dollar itself has undergone a metaphysical transformation."

They are willing to make adjustments as needed and are unwilling to let emotion, regret, or speculation about future policy changes influence their choices. As Spock once explained after experiencing some bad luck earlier in life, "The odds of failure were 0.4%. Unfortunately, probability does not prevent outcomes – it merely predicts them. Regret would be an inefficient use of processing power."

Spock and T'Lara have been diligent savers, accumulating a portfolio of $10 million with plans to spend $10k per month in retirement. They think the risk of future cuts to Social Security is low and effectively zero for people their age. If they defer Social Security, they will set up a TIPS ladder within their bond allocation that would replace the income they otherwise would have received. They both have longevity in their family. Spock's father, Sarek, lived to an age of 202, although Spock and T'Lara are comfortable being more conservative and only planning to age 100. At 62, they'll be eligible for $5k per month in combined Social Security benefits.

Again, the first factor to consider is the appropriate discount rate to start with as a baseline. In this case, it's feasible and actually planned that any Social Security delay would be covered with funds carved out of their fixed income allocation and funded with TIPS, specifically. Therefore, in this case, a 0% (or even negative if the TIPS yield curve would indicate) rate may be appropriate. We'll use a 0% real assumption as a baseline.

From there, we might make relevant client-specific adjustments as follows:

- Mortality Risk: +0.5% (Mortality risk is always present, but this is a relatively small risk for Spock and T'Lara.)

- Sequence of Returns Risk: +0.0% (The size of Spock and T'Lara's portfolio combined with their desired spending levels and funding all of their delayed Social Security income with a TIPS ladder effectively immunizes them from any additive sequence of returns risk from choosing to delay claiming.)

- Regret Risk: +0.0% (They might comprehend the human concept of regret, but it's not something they would personally experience.)

- Health Span Risk: +0.0% (They are committed to not allowing the source of their income to influence their spending behavior.)

- Spending Optionality/Flexibility Decline Risk: +0.0% (Fully funding their $72k of annual Social Security income from their $10 million portfolio has no meaningful impact on spending optionality.)

- Underspending Risk: +0.0% (Again, they're committed to not allowing their income source influence their spending behavior.)

- Longevity Risk: -4.0% (Although they are comfortable planning to only age 100, Spock's father lived to age 202, which means longevity risk plays a dramatically larger role in their discount rate.)

Netting these adjustments leads to a –3.5% discount rate for Spock and T'Lara.

Finally, Spock and T'Lara aren't concerned about future benefit cuts and find that unlikely, so we do not need to account for that concern here.

Here are the results for Spock and T'Lara:

As we can see, in Spock and T'Lara's case, claiming at age 70 is a clear winner. Not only was this generally true based on their longevity and sourcing income from a TIPS portfolio (making 0% a reasonable baseline discount rate), their situation was also exacerbated by factoring in other risks and actually ending up with a –3.5% discount rate.

Beyond The Numbers: What This Means

The main takeaway here is that a proper discount rate for a Social Security claiming analysis is not simply 0%, as is so often assumed in research. If we're going to use an expected value framework to apply a discount rate, we should start with the portfolio's expected rate of return and then adjust that further based on how susceptible the client is to related risks.

Notably, for many Americans, it's reasonable to assume real discount rates of 4% or higher once all risks are considered – high enough to flip optimal claiming strategies from delaying to claiming early. Most current Social Security research 'stress tests' results with real discount rates in the ~2% range, but this is nowhere near high enough to actually stress results in most cases.

Furthermore, while approaching this question from a different angle, this is also consistent with some recent research that has challenged the notion that many Americans are making a mistake by filing early. For instance, in a 2024 Journal of Financial Planning article, Smith and Smith conclude:

Our calculations do not support the presumption that the vast majority of people who choose to start their Social Security retirement benefits before age 70 are making a mistake. For example, … with a 4 percent real return, a person has to live to 89 for it to be beneficial to delay the start of benefits from age 67 to 70. However, 77 percent of 67-year-old males die before 89 as do 65 percent of 67-year-old females. Age 70 is not the most financially rewarding age to initiate benefits unless an individual has a low discount rate and/or is confident they will live several years past their life expectancy.

Ultimately, the key point is that we need to move beyond simply thinking in terms of portfolio risk when assessing Social Security claiming analysis discount rates. Ideally, we should be thinking more in terms of utility and factoring in all risks, which changes the calculus significantly. This doesn't necessarily mean abandoning discount rates – it means using ones that reflect opportunity cost, behavior, and the messy realities of retirement. And when viewed this way, it's extremely unlikely for 0% to be the correct discount rate for most retirees!

Disclosure: Derek Tharp is the Head of Innovation at Income Lab. Income Lab was used in calculating some examples included in this article.

![Guvenen et al [] and Blanchett et al [] Earnings Curves Guvenen et al [] and Blanchett et al [] Earnings Curves](https://www.kitces.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/06-Guvenen-et.-al-2016-and-Blanchett-et-al.-2017-Earnings-Curves.png)

Very good article! My particular circumstances made delaying until 70 a no-brainer. But I could also see that for many people that just didn’t make sense. Especially if, for example, you could retire at 65 if you started taking SS but had to keep working in order to delay (a situation many, many people are in). There are so many factors that go into to this.