Executive Summary

(Note: For an updated discussion of the final 2025 "One Big Beautiful Bill Act", see Breaking Down The “One Big Beautiful Bill Act”: Impact Of New Laws On Tax Planning)

In recent years, there's been uncertainty over whether the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) will be allowed to 'sunset' at its scheduled expiration date of December 31, 2025, which would revert many current tax rules to their pre-2018 status. Although the 2024 U.S. elections resulted in a Republican 'trifecta' that made a TCJA extension in some form likely, the narrow Republican majorities in the House and Senate have slowed progress toward drafting a bill to extend or replace TCJA. Which has made it difficult for advisors and their clients to plan for the future with less than a year remaining before the scheduled sunset.

Recently, however, the House and Senate agreed to adopt a budget resolution that represents a crucial first step in the process of passing a 'reconciliation' bill. Although it doesn't contain specific provisions for what will be included in the new bill, it provides a general framework for the bill's overall 'cost' to the Federal deficit, offering planners some idea of the bill's potential scope and providing at least some certainty for clients planning their taxes for 2026 and beyond.

The budget resolution differs in key ways between the framework it provides for the House of Representatives and the Senate, meaning that we could see draft legislation from both chambers that would need to be reconciled to produce a final bill for the president to sign.

In the House's version, the budget resolution authorizes $4.5 trillion in tax cuts over the next 10 years, which would mostly cover the estimated $4.6 trillion cost of extending TCJA (plus some already-expired provisions). However, the House's proposal would leave little room for additional tax cuts proposed by President Trump and Republican legislators, including raising the $10,000 limit on State And Local Tax (SALT) deductions and eliminating taxes on tip income. To fit within the House's budget framework, legislators would need to either shorten the bill's 'sunset' window (e.g., to five or six years versus TCJA's eight-year window), eliminate some new or existing provisions, or include selective tax increases to offset additional tax cuts.

By contrast, the Senate's version authorizes 'only' $1.5 trillion in tax cuts – but due to a controversial legislative accounting tactic, that amount includes the cost of permanently extending TCJA, meaning the $1.5 trillion represents additional tax cuts beyond TCJA's extension. In other words, Senate Republicans aim to make TCJA's rules permanent while layering in new tax cuts that would sunset after 10 years.

The difficulty is that, with only a handful of votes to spare in both the House and Senate, congressional Republicans could struggle to find a bill with enough support to pass in both chambers. For example, many House Republicans say they will only support a bill that includes cuts to programs like Medicaid, while others oppose any substantial Medicaid cuts. So while a bill like the Senate's proposal could potentially make TCJA permanent and add additional tax cuts, it may prove politically unfeasible if it requires deep spending cuts to reduce its impact on the deficit.

The key point, however, is that even though there may be significant disagreements to overcome among Republicans before they can align on a reconciliation bill, TCJA's impending sunset deadline will increase pressure to pass something to prevent the tax rules from rolling back to their pre-2018 status. And even though negotiations may continue to drag out the process of drafting and passing a final bill, it still makes sense for advisors and their clients to take a "wait and see" approach to tax planning (while being reasonably confident that there will at least be a tax bill passed by the end of the year!).

TCJA's Sunset Date Means Tax Cuts Are The Biggest GOP Legislative Priority For 2025

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 was a sprawling piece of legislation that touched many parts of the U.S. tax system. The marginal tax brackets that are in use today (both the tax rates themselves and the thresholds between brackets) were set by TCJA, as were the current standard deduction, Child Tax Credit, Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) exemption, and Gift & Estate Tax exemption amounts. TCJA also eliminated personal exemptions for each taxpayer and their dependents, created a $10,000 limit on the State And Local Tax (SALT) itemized deduction, and eliminated miscellaneous itemized deductions such as investment management fees and unreimbursed employee expenses. Additionally, TCJA created the Section 199A deduction for up to 20% of Qualified Business Income (QBI) for pass-through business owners (along with many other less-impactful provisions).

In other words, much of the U.S. individual income and estate tax system today is the result of TCJA's enactment in 2017. Which makes it a big deal that most of TCJA's provisions are scheduled to expire under current law on January 1, 2026. If TCJA is allowed to 'sunset' as scheduled, then most of the Internal Revenue Code – including all of the areas described above – will revert to how it existed before TCJA was signed into law on December 22, 2017. That would result in at least a moderate tax increase for most households and, at minimum, a scramble for taxpayers (and the professionals advising them) to refresh their understanding of the pre-TCJA rules, which by then will not have been in effect for eight full years.

With the potential for TCJA's sunset broadly affecting so many households, many financial advisors have fielded questions from their clients on what they can do to prepare. If TCJA sunsets and tax rates go up, for example, it could make sense for some clients to make Roth conversions to pay tax at a lower rate than they would if their tax rates were to increase after 2025, or to defer some business expenses to deduct from (higher-taxed) income if the Sec. 199A deduction were to expire.

And on the estate tax side, the difference between gifting assets now, with the Gift & Estate Tax Exemption at $13.99 million per individual, or after TCJA's expiration, when it decreases by 50% to about $7 million per individual, could amount to millions of dollars in estate taxes owed… if TCJA expires as scheduled. So, for financial advisors, it's helpful to stay on top of legislative developments that can point to whether or not TCJA will be allowed to expire – and if it is extended in some form, what shape the new legislation that replaces it might take.

Why TCJA Needed To "Sunset"

The reason TCJA was written to include a scheduled expiration date is that it was passed through the 'reconciliation' process, which allows tax and spending bills to pass through the U.S. Senate with a simple majority vote. By contrast, in the 'normal' legislative process, senators who oppose a bill can block its passage through the filibuster, which requires 60 votes to overcome. The Republicans at the time who wrote TCJA held majorities in both the House and Senate but lacked the 60-vote Senate supermajority needed to pass bills through the normal legislative process, and so reconciliation proved to be their only option to pass a tax-cut bill that had long been one of their policy priorities.

The reconciliation process has numerous rules meant to limit its use to specific short-term budget-related legislation, with one of the key rules being that a reconciliation bill's provisions cannot increase the Federal budget deficit beyond a 10-year window. Since tax cuts decrease revenue, they typically increase the deficit, which means any tax-cut law passed via reconciliation must expire within 10 years unless offset by tax increases (or spending cuts) elsewhere.

When congressional Republicans passed TCJA in 2017, they set most of the law's provisions to expire after December 31, 2025 – setting up a situation where the results of the 2024 U.S. presidential and congressional elections would dictate which party would be in power upon TCJA's expiration and, therefore, who gets to decide whether it will be extended, replaced with different legislation, or allowed to sunset as scheduled.

Where We're At In The Legislative Process

In the years leading up to the 2024 elections, there was significant anxiety about whether TCJA would be allowed to sunset. But it was largely expected that, should Republicans hold power, they would extend TCJA beyond its original expiration date and perhaps go even farther in cutting taxes. As it turns out, Republicans did take power, with Donald Trump elected as president and Republicans gaining majorities in both the Senate and House of Representatives (although the majorities are slim, with margins of 53–47 in the Senate and 220–213 in the House).

However, just as in 2017, Republicans lack a 60-vote supermajority in the Senate to overcome any potential Democratic filibusters. And unlike in 2012–2013 – when Republicans and Democrats negotiated a deal to permanently extend most of the George W. Bush-era tax cuts that were originally passed via reconciliation and were set to expire at the end of 2012 – there appears little likelihood of both parties coming together to negotiate a bill that avoids TJCA's expiration. Which means that Republicans must once again go through the reconciliation process to pass legislation that either extends or expands on TCJA.

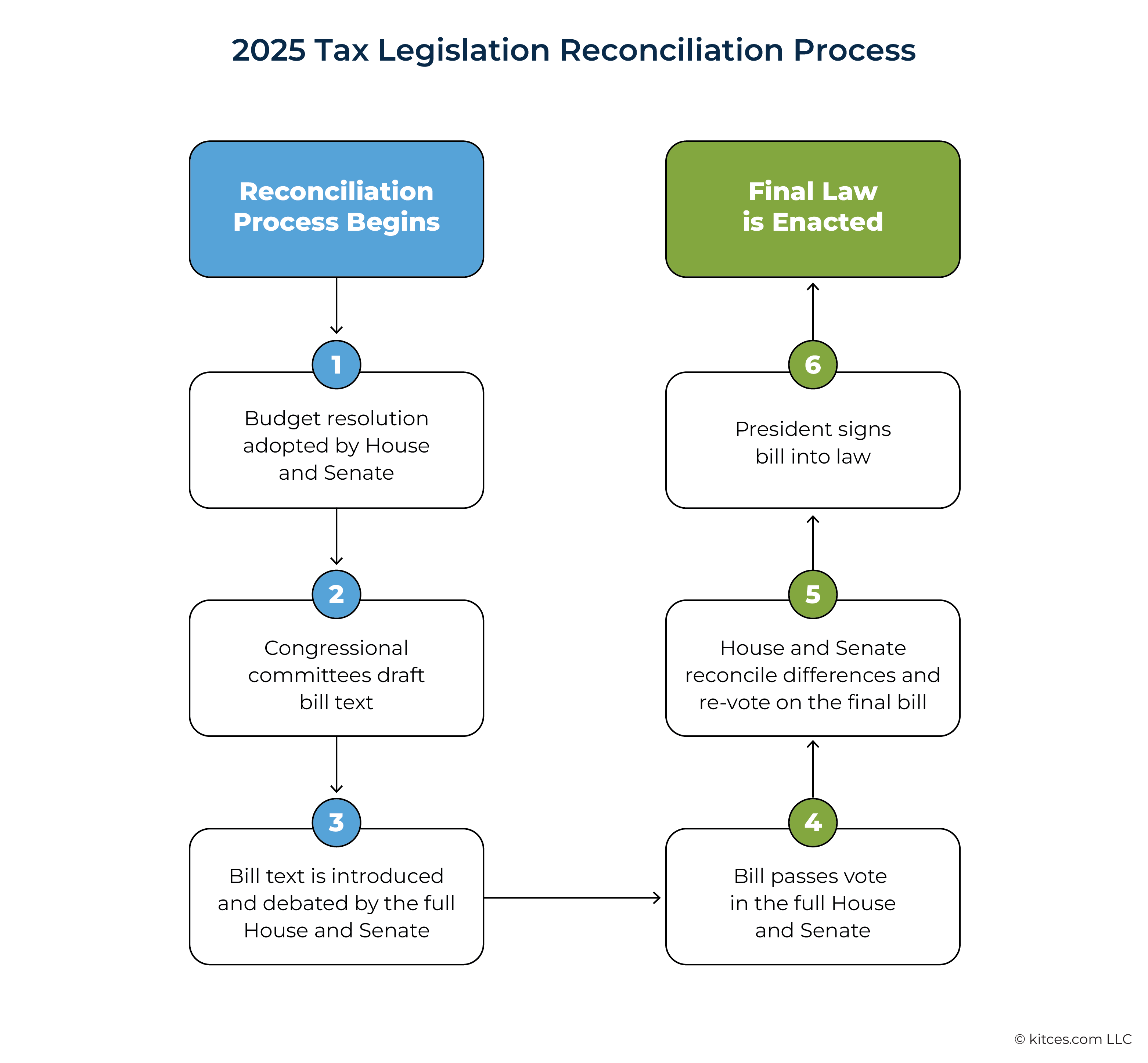

In a rough sense, the reconciliation process resembles the traditional way in which a bill becomes a law. In both chambers of Congress, committees write and debate the bill text, which is then introduced for a vote. After each chamber passes its own version, the House and Senate reconcile any differences between the two bills and, if changes are made during that process, re-vote on the final language before sending it to the president to be signed into law.

Reconciliation adds one additional step to the beginning of this process: Before the text of any bill is written, the Senate and House must adopt a budget resolution that sets revenue and spending targets for each congressional committee. This resolution essentially creates the framework for how much each committee's legislation can increase or decrease Federal revenue or spending.

For example, the budget resolution might instruct the House Ways and Means Committee (which creates tax legislation) to submit a bill that increases the Federal budget deficit by up to $1 trillion. That means the committee could propose up to $1 trillion in net tax cuts. Legislators can negotiate to change the bill's total cost later in the process, but the initial budget resolution is a mandatory starting point that helps set the general tone for what's likely to be included in the final legislation.

As of this writing, the status of the Republicans' reconciliation bill is that the House and Senate have agreed on a budget resolution on two narrow votes, with the Senate adopting the resolution on a 51–48 vote on April 5, 2025, and the House adopting the same version on an even closer 216–214 vote on April 10, 2025. As shown in the graphic outlining the reconciliation process below, the next step is for both chambers' respective congressional committees to write the first draft of the new legislation.

Breaking Down The House And Senate Budget Resolutions

At this point, there's no draft text of a potential reconciliation bill to extend or replace the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), which means there's nothing specific yet to analyze for financial planning implications. And unlike in the wake of the 2016 election – when both the Trump campaign and House GOP released detailed tax plans that outlined their policy priorities (even though much of it was abandoned) – there's no comparable tax policy proposal today. Neither congressional Republicans nor the president have released a tax policy platform that signals what the current administration and Congress might prioritize. In other words, we don't yet know what the reconciliation bill might contain, beyond 2024 campaign trail promises (such as eliminating taxes on tips, overtime, and Social Security income) and public comments from members of Congress – who appear to agree only on the need to pass something to avoid the pre-2018 tax law going back into effect.

However, the House and Senate budget resolution adopted in early April may offer some clues about what the reconciliation bill could include. Although it doesn't contain any specific policy provisions, the overall budget targets offer insight into the likely scope of the final legislation. Much like how a financial planner might estimate a client's budget from their family's total income and spending without knowing any of the individual line items, we can infer the broad strokes of the pending bill by examining the top-level numbers.

Notably, the adopted budget resolution contains two separate sets of instructions for the congressional committees drafting the reconciliation bill: one for the House of Representatives and one for the Senate. This suggests the two chambers may produce two separate versions of the bill, requiring future negotiation to reconcile any differences before the bill can become law. As a result, it's helpful to examine what each version of the budget resolution implies about the tax legislation that could extend or replace TCJA.

House Proposal: Temporary Tax Cuts With Accompanying Spending Cuts

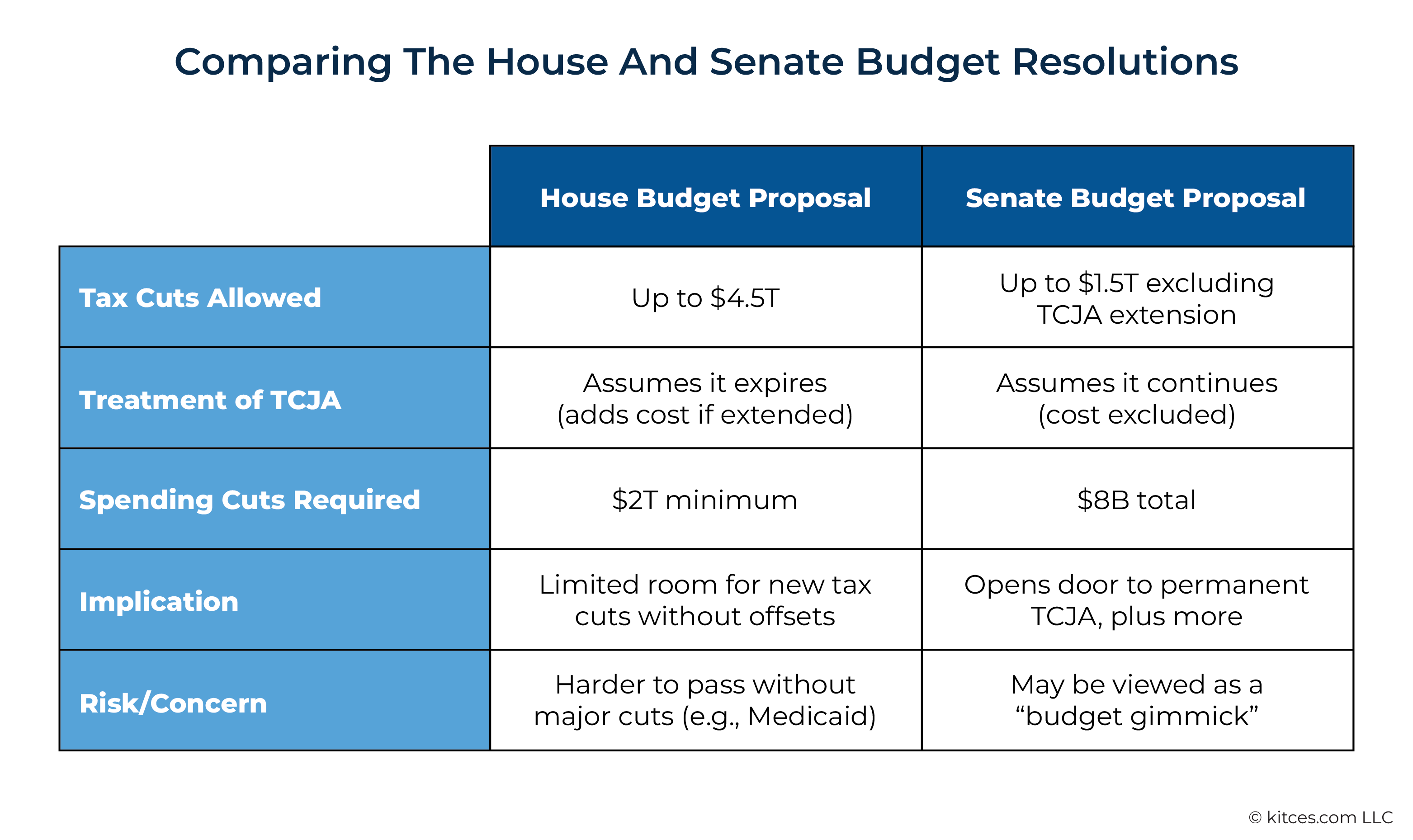

The House of Representatives' section of the budget proposal instructs the House Ways and Means Committee (which handles all tax-related legislation) to submit legislation that raises the Federal budget deficit by no more than $4.5 trillion over the 10-year period from fiscal years 2025 through 2034. In other words, the bill may include up to $4.5 trillion in net tax cuts.

For context, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has estimated that fully extending TCJA's expiring provisions would increase the deficit by about $4 trillion over the next 10 years, while restoring several popular business deductions that have already been phased out under TCJA (such as 100% bonus depreciation, full expensing of research and development expenses, and allowing depreciation, amortization, and depletion to be included in business income for purposes of calculating the business interest deduction limit) would add another $600 billion.

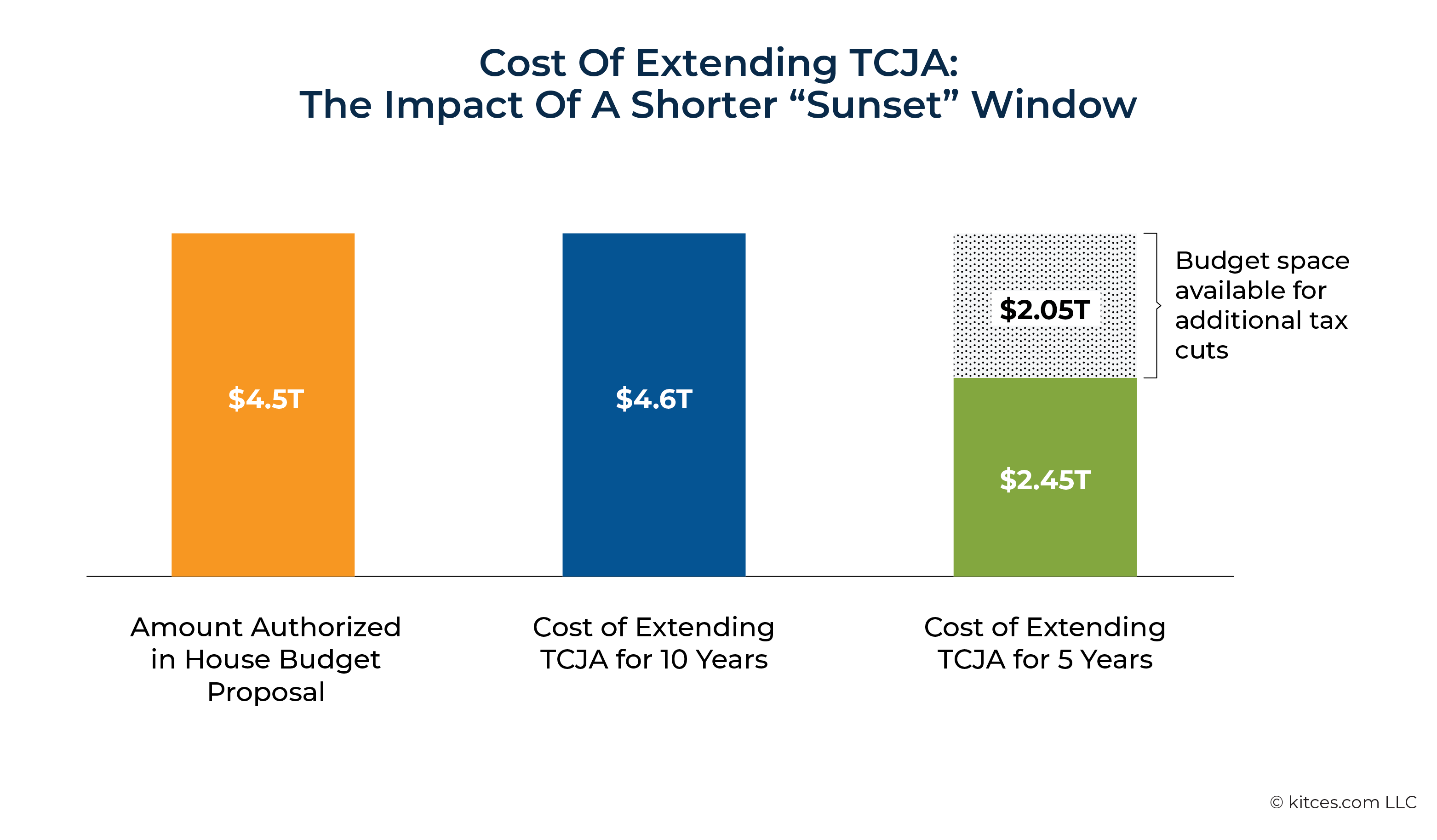

Which means that the House's proposed $4.5 trillion level of tax cuts wouldn't quite cover the full $4.6 trillion cost of extending TCJA over 10 years, even before accounting for other proposed tax cuts, such as raising or eliminating the $10,000 cap on the State And Local Tax (SALT) deduction.

The House's budget proposal also ties the amount of allowable tax cuts to a corresponding level of spending reductions across other government agencies. Specifically, the proposal specifies that if total spending cuts are less than $2 trillion, then the amount of allowable tax cuts must be reduced as well. This level of spending reduction would almost certainly require cuts to the Federal Medicaid program, which provides low- or no-cost healthcare to people in low-income households and other qualifying groups. Yet some Republicans in both the House and the Senate have stated that they wouldn't vote for a bill that includes substantial cuts to Medicaid. So there will clearly be additional negotiation needed to craft a bill that contains enough spending cuts to appease the deficit hawks without losing the support of Republicans who oppose Medicaid cuts, since the narrow Republican majority means that both groups will need to vote for the bill for it to pass through both chambers of Congress.

In all, the House's budget resolution points to a relatively narrow package of tax cuts, mostly focused on preserving the existing provisions of TCJA rather than adding much (if anything) else.

If House Republicans want to add new tax cuts – such as increasing the SALT deduction limit (as many legislators have expressed the desire to do), eliminating taxes on tips (as Trump pledged on the campaign trail), or repealing the estate tax entirely (as has long been a Republican priority and is the aim of a bill that's already been introduced in the Senate this year) – they would need to consider other options to stay under the $4.5 trillion cap. One option would be to use a shorter 'sunset' period: According to the CBO's estimate, the cost of fully extending TCJA would drop to around $2.45 trillion if the extension lasted five years instead of ten, leaving over $2 trillion for additional provisions before hitting the $4.5 trillion threshold.

Legislators could also decide to swap out some current TCJA provisions (or already-expired provisions that could be restored with an extension of TCJA) to pay for some of the new provisions they've proposed. For example, the Congressional Budget Office's projection shows that restoring 100% bonus depreciation would add an estimated $385 billion to the deficit over the next 10 years. If Congress left that provision out of the reconciliation bill, they could potentially double the SALT deduction cap to $20,000 for married filers (at an estimated cost of $175 billion) and eliminate taxes on tips (estimated at $118 billion), while still reducing the overall net cost of the bill by $92 billion. So the House bill could see both the addition of new provisions and the repeal of existing ones as legislators try to solve the puzzle of fitting the bill's cost within their budget framework.

Another step Republicans could take is to include tax increases in the bill to offset other tax cuts. For example, they could repeal clean energy tax credits introduced by the Inflation Reduction Act under the Biden administration, such as credits for electric vehicles and home energy efficiency improvements, which Republicans targeted for repeal before they gained their trifecta in the government (although some oppose repealing those credits because they impact many jobs in Republican-represented congressional districts). Some Republicans have also suggested raising the top individual tax bracket to 39.6% (where it was prior to TCJA), though it's also unclear whether there would be enough support for such an increase to make it into the final bill, given how many Republicans have repeatedly pledged to cut taxes further. Either way, with only a narrow 220–213 majority in the House, Republicans face a difficult road ahead in considering proposals to adopt that won't cost them the handful of votes needed to pass the bill.

Senate Proposal: Making Way For A Permanent TCJA Extension?

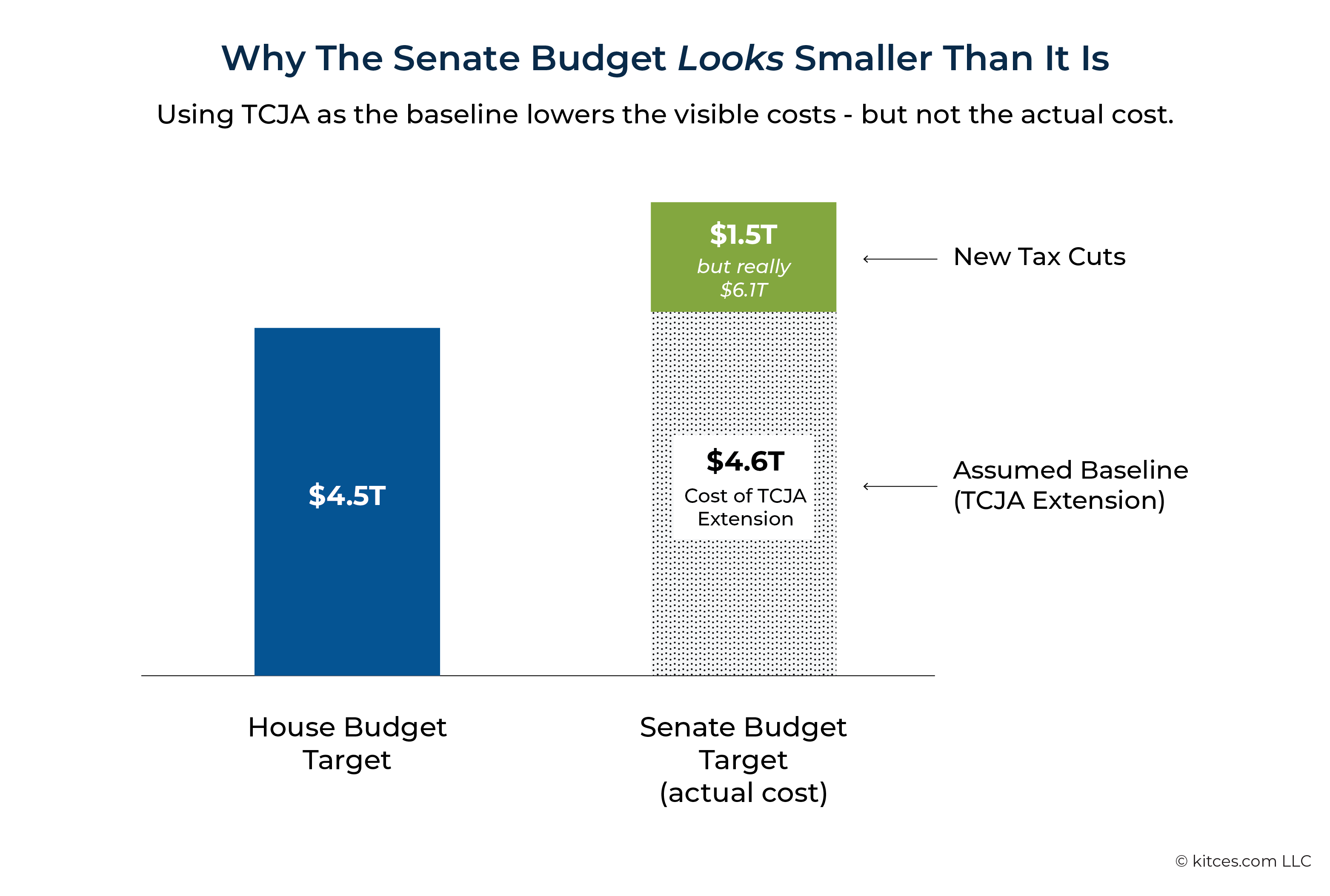

The Senate's section of the budget proposal takes a very different approach than the House's. The Senate Committee on Finance (which has jurisdiction over Senate tax legislation) is instructed to submit legislation that raises the Federal budget deficit by no more than $1.5 trillion – again, meaning that the bill may include up to $1.5 trillion in net tax cuts. And unlike the House's target of $2 trillion in total spending cuts, the Senate version targets 'just' $8 billion in total cuts (which, in the context of the Federal government and its $6+ trillion in overall spending each year, represents a comparative drop in the bucket).

On the surface, the Senate's $1.5 trillion cap might seem like a more modest target than the House's $4.5 trillion proposal. However, Senate Republicans adopted a controversial tactic to reduce the apparent budgetary cost of their legislation: They treated the full extension of TCJA as having no cost at all. Their reasoning is that because TCJA is currently in effect, it should serve as the baseline for future budget projections – even though it's legally scheduled to sunset at the end of this year.

In other words, the $1.5 trillion cap only applies to new tax cuts over and beyond a full TCJA extension. Given that the CBO estimates the cost of fully extending TCJA at $4.6 trillion, the 'real' cost of the Senate's budget proposal is $1.5 trillion + $4.6 trillion = $6.1 trillion – well above the House's $4.5 trillion limit.

Perhaps the most significant implication of the Senate's decision to use the current TCJA-era tax rules as the baseline for its budget proposal is that it lays the groundwork for extending those rules permanently, rather than requiring another sunset date within 10 years of the law taking effect.

As mentioned above, reconciliation rules generally prohibit any revenue or spending provisions from increasing the Federal budget deficit beyond a 10-year budget period. Traditionally, this calculation follows what's known as the "current law baseline" (which the House followed in its budget resolution), where the assumption is that TCJA will expire at the end of 2025, as required under current law. If TCJA is allowed to sunset as scheduled, Federal revenues would increase as the pre-2018 tax rules kick in and overall tax rates rise. But if TCJA is extended, it reverses that scheduled revenue increase, thereby decreasing future revenue and increasing the projected deficit – triggering the requirement that the extension must also expire within 10 years.

By contrast, the Senate's approach uses a "current policy baseline", treating the current TCJA rules as permanent, rather than temporary, by default. Which means that, under the Senate's proposal, there is no budgetary impact of extending TCJA, and therefore no need for a sunset provision. This strategy creates room to make the TCJA rules permanent while still allowing for $1.5 trillion in additional tax cuts (which themselves would need to expire within 10 years under reconciliation rules). And because the extension isn't scored as increasing the deficit, the Senate proposal avoids the pressure to offset the cost through spending cuts to programs like Medicaid.

What makes the "current policy baseline" method so controversial is that it doesn't change the bill's actual fiscal impact – just how it's presented. Critics, including some Republicans, have described this tactic as a "gimmick" that masks the true cost of the legislation. One analogy likens it to a person buying a $100,000 sports car in one year, doing the same thing the following year, and pretending that the second car has no impact on their budget because it merely represents a continuation of their 'existing' spending.

Furthermore, it's still uncertain whether the Senate parliamentarian – who traditionally decides whether the Senate is complying with the rules for reconciliation bills – will allow this tactic, or whether Senate Republicans will simply move forward with their bill regardless of the ruling.

The key point is that if the Senate passes a bill that aligns with their section of the budget proposal, it would likely make permanent the TCJA-era rules that taxpayers have grown accustomed to over the last eight years. (Though no tax law is ever truly permanent – future Congresses can always amend or reverse legislation.) The bill could also layer in additional significant tax cuts, subject to their own sunsets. Still, Senate Republicans may have challenges getting such a bill passed into law without adding significantly more spending cuts to appease House Republicans focused on reducing Federal spending.

What's Happening Next?

The discrepancy between the House and Senate versions of the budget resolution highlights some significant differences between how the House and Senate Republicans are approaching this year's reconciliation bill. Most notably, they disagree over whether TCJA should be made permanent or extended with another (maximum) 10-year expiration date, and how deep spending cuts (especially to programs like Medicaid) should go to satisfy both chambers. These divisions could complicate Republican leadership's stated goal of having a bill ready for the president to sign by Memorial Day 2025.

Even so, recent history suggests that Republicans may be willing to overcome those differences in order to get a reconciliation bill passed. For instance, some House Republicans initially resisted passing the current budget resolution on the grounds that its $2 trillion spending cut target didn't go far enough, and because it didn't require the Senate to include similar levels of spending cuts in its version of the budget resolution – raising concerns among House Republicans, that, without a firm commitment from the Senate, the final compromise bill would further dilute the deeper cuts they had pushed for.

However, the holdouts in the House eventually gave in and passed the budget resolution as-is, with their desire to move any bill forward overpowering their willingness to hold up the legislation over their individual concerns at this key point in the reconciliation process. Which raises the question: If they weren't willing to stand in the bill's way at that point, will they ever be willing to do so, given that there will be even more pressure to vote for the bill as it's nearing final passage (and the added pressure of TCJA's sunset date looms closer)?

Still, with such slim majorities in the House and Senate, even a few holdouts among the Republican caucus could hold up the reconciliation bill's passage. And with so many competing priorities – from the SALT cap to Medicaid cuts to the Inflation Reduction Act's clean energy credits – the risk of an intra-party blockage remains. There also appears to be genuine concern among some Republicans about the budgetary impact of extending and expanding TCJA's tax cuts, as the reported willingness from some Republicans to consider raising the top marginal tax rate to 39.6% demonstrates. Which suggests there will likely be pressure to at least attempt to lower the cost of the final bill, whether by narrowing the scope of additional tax cuts or making politically unpopular spending cuts.

The bottom line, however, is that while there may be a long negotiating process before House and Senate Republicans can agree on a final reconciliation bill that can pass both chambers – with a timeline that could stretch well beyond the Memorial Day target – the one thing every Republican appears to agree on is that they don't want TCJA to lapse on January 1. What ends up in the final bill, and whether it more closely resembles the House's or the Senate's version of the budget proposal (or something else entirely), remains to be seen. But the farther we get into 2025, the more pressure there will be on congressional Republicans to set aside internal disagreements and pass a bill – any bill – that keeps TCJA alive in some form or another.

For advisors and their clients, then, it's reasonable to expect that the Federal tax rules won't go back to their pre-TCJA versions, but it's still best to take a "wait and see" approach to implementing any tax planning strategies until there's more certainty on what exactly the next tax legislation will contain.

Leave a Reply