Executive Summary

Financial advisors are used to having close and trusting relationships with their clients, given the advisor's involvement in the intimate details of the client's financial life and the long-term nature of many advisor-client relationships. And it therefore occasionally happens that a client asks their advisor to serve as trustee for a trust they've created. But while being asked to serve as a client's trustee may be a testament to the depth of the relationship, advisors should think twice in most cases before accepting such an appointment. Because while no regulations outright prohibit advisors from acting as trustees, the ethical, fiduciary, and legal conflicts that accompany serving as a client's trustee can often make it more trouble than it's worth.

At one level, advisors who act as both trustee and investment manager of a trust face an inherent conflict of interest, since they stand to benefit from the compensation they receive for managing the trust's assets. Which isn't necessarily prohibited under trust law, but does leave advisor-trustees open to having their decisions challenged by trust beneficiaries, where the advisor bears the burden of proving they acted reasonably and in good faith. Advisors must be prepared to demonstrate not only the prudence of their investment choices but also the fairness of their compensation arrangements with respect to the trust's beneficiaries.

Compounding this, conflicts can also arise from the dual fiduciary obligations advisors owe when a client is also a trust beneficiary. Advisors are bound to act in their clients' best interests, but trustees must remain neutral among beneficiaries, which may be impossible to reconcile when not all trust beneficiaries are clients of the advisor. For example, if an advisor-client requests a distribution that another beneficiary opposes, the advisor-trustee must navigate a fiduciary gray area where impartiality is required but loyalty to the client is also expected.

Regulatory considerations further complicate the matter. Advisors who serve as trustees are generally deemed to have custody of trust assets by the SEC and state regulators, requiring annual surprise audits – a time-consuming and expensive process typically borne by the firm. While there are exceptions for close family relationships or co-trustee arrangements, these are narrow and often impractical. For RIAs, being named as a successor trustee (stepping in only upon a client's death or incapacity) can temporarily avoid custody, but full compliance becomes necessary the moment the advisor assumes control of the trust. Similarly, broker-dealer representatives face their own hurdles, as FINRA rules require pre-approval and ongoing supervision from the broker-dealer firm before acting as a client's trustee, adding yet another layer of oversight.

Given these layers of complexity and risk, most advisors are better served by declining one-off trustee appointments unless they are prepared to offer trustee services as a structured, professional line of business. Advisors who pursue this route must establish clear client acceptance criteria, liability protection (including E&O coverage and legal entity structuring), and robust operational systems to fulfill their administrative and fiduciary responsibilities. These include managing distributions, tax reporting, beneficiary communication, and ongoing investment management. Done right, such a service can be a compelling value-add for high-net-worth clients who prefer a 'one-stop shop' for wealth and trust management, and can also serve as a differentiator in a competitive marketplace.

Ultimately, the question of whether to serve as a trustee comes down to intentionality and infrastructure. Advisors who say yes must be fully equipped – legally, operationally, and ethically – to fulfill both roles without compromise. For everyone else, the more prudent path is to build strong referral relationships with qualified corporate trustees or attorneys who can fulfill that role, ensuring clients' needs are met while protecting the integrity of the advisor-client relationship. Either way, the goal remains the same: to honor the immense trust clients place in their advisor by ensuring their wishes are carried out with competence, impartiality, and care!

Martha, a financial advisor, is meeting with her client Roger to hammer out the last details of Roger's estate plan that they have been working on with his estate planning attorney. It has been a long process, with many calls and emails back and forth between Martha, Roger, and the attorney over the last several months, but they're finally nearing the point where the estate documents can be drafted and signed.

One item on Martha's to-do list for the meeting is to ask Roger whom he wants to serve as trustee for the irrevocable trust he's establishing as part of the estate plan. When she asks the question, Roger gets quiet for a moment, looking more nervous than Martha has seen in their years of working together.

Finally, he opens his mouth to speak: "Well, I was wondering if you wanted to be the trustee."

What should Martha say here? If she's never served as a trustee before or isn't comfortable taking on the fiduciary duty and legal liability of acting as a trustee (on top of her own duties as an advisor), she may politely turn down Roger's request and offer to connect him with an attorney or corporate trustee with experience in carrying out that role.

But does Martha need to turn down a client's request to serve as a trustee? That answer is more complicated. While there are no explicit rules forbidding advisors from taking on trustee relationships, it isn't a decision to be taken lightly, as there are ethical and regulatory issues that can prove perilous for both advisors and clients. However, in some cases, serving as a trustee can be a powerful way for advisors to add value as part of a 'high-touch' service offering geared toward high-net-worth clients.

So for advisors who've considered serving as a client's trustee – or for those who, like Martha in the scenario above, have been asked by a client and haven't been quite sure what to say – it's helpful to understand what the ethical and regulatory considerations are and to learn some best practices (including from RIAs that currently offer trustee services) for delivering trustee services effectively. Advisors can then construct their firm's policies regarding whether and how to serve as trustee – whether by referring clients to corporate trustees, accepting trustee roles on a limited case-by-case basis, or building a more robust trustee service offering to serve existing clients and attract more affluent prospects.

Issues With Financial Advisors Serving As Trustees

The job of a trustee is to manage a trust on behalf of its beneficiaries according to the instructions laid out in the trust instrument. Trustees may have specific duties required of them by the trust – such as distributing trust income to beneficiaries under certain conditions, maintaining and insuring real estate property held by the trust, or filing the trust's tax return each year. But they may also have wide discretionary authority over administering the trust, including the ability to invest trust assets, write checks from the trust's accounts, or even add or remove beneficiaries.

Trustees also have a fiduciary duty to the trust and its beneficiaries, requiring them to act reasonably in managing trust assets and to put the trust beneficiaries' interests before their own. When trusts have multiple beneficiaries, trustees must act impartially and cannot favor one beneficiary's interests over another's. Under trust laws such as the Uniform Trust Code (UTC), which has been adopted by 35 states and Washington, DC, these duties cannot be waived or overridden by the terms of a trust.

These duties and requirements of trustees introduce some conflicts of interest for a financial advisor serving as trustee for a client's trust.

Compensation Conflicts Between Advisors And Trusts

Trustees often have the power to delegate investment management of trust assets to a third-party manager. A financial advisor serving as a trustee could – and in almost all cases presumably would – delegate this duty to themselves in their role as financial advisor. If the advisor were paid to manage the trust's investments (which, in all likelihood, they would be), a conflict of interest would arise between the trustee's duty to act in the best interests of the trust's beneficiaries and the advisor's financial incentive to be compensated for managing the trust assets. Advisors who bill based on AUM would also be incentivized to minimize distribution of trust assets – even when doing so would be in the beneficiaries' best interests – to maximize the amount of billable assets remaining within the trust.

Trust laws such as the Uniform Trust Code (UTC) address these types of conflicts by allowing beneficiaries to challenge in court certain transactions or arrangements that may be affected by a trustee's fiduciary and personal conflicts of interest. If a transaction is shown to violate the trustee's fiduciary duty – that is, if the trustee allowed the conflict to influence their decision-making regarding the transaction – then it may be voided by the court.

Certain transactions are presumed to be affected by the trustee's conflict of interest, meaning the trustee must prove that they acted fairly and in good faith while deciding on the transaction, while for other transactions the burden of proof falls on the beneficiary to show that the trustee failed to follow their fiduciary duty.

For instance, a financial advisor serving as trustee who is also paid to manage the trust's investments would most likely fall under the category of having a presumed conflict. If a beneficiary of the trust were to challenge the arrangement, the advisor would need to show that they acted reasonably and in good faith in selecting themselves, rather than an outside manager, to handle the trust's investments. More specifically, the advisor would need to show that they invested the trust's assets prudently and in accordance with the beneficiaries' investment objectives, and that they did not charge excessive fees (e.g., more than an outside manager would have charged to provide the same service).

However, the UTC applies slightly looser standards specifically in cases where trustees receive compensation from mutual fund companies – such as broker-dealer representatives who invest trust assets in mutual funds on a commission basis. In those cases, a trustee's receipt of compensation for recommending a mutual fund is not presumed to be affected by a conflict of interest if a beneficiary challenges the transaction. While trustees must still act in the beneficiaries' best interests when choosing mutual funds, beneficiaries carry the burden of proving otherwise if they decided to challenge those trustee's investment decisions.

The bottom line is that, regardless of their compensation method, advisors serving as trustees must invest trust assets prudently and act in the best interest of the trust's beneficiaries. Investment advisory fees, underlying fund fees, and commissions should all be in line with what the trust would pay an independent third-party investment manager. And if a beneficiary decides to challenge the arrangement in which the advisor/trustee charges separately to manage the trust's investments, the advisor will need to prove that they acted reasonably and in good faith in delegating investment management duties to themselves – unless the arrangement qualifies for the mutual fund commission exception. Even then, the advisor must still take care to ensure their compensation incentives do not conflict with their duty to act in the beneficiaries' best interests!

Competing Fiduciary Duties Between Trust Beneficiaries And Advisory Clients

Another possible issue with advisors serving as a trustee is in cases where the trustee's fiduciary duty to the trust's beneficiaries conflicts with the financial advisor's own fiduciary duties to their clients. If the advisor has any clients who have competing interests with any of the trust's beneficiaries, the advisor's requirement to act in both parties' best interests – one as the client of the advisor, and one as the beneficiary of a trust where the advisor serves as trustee – can result in an irreconcilable conflict.

Example 1: Aaron is a financial advisor serving as trustee of a trust. The trust has two sibling beneficiaries, Brian and Claire. Brian is also an advisory client of Aaron, while Claire is not.

As trustee, Aaron has a fiduciary duty to both Brian and Claire (the beneficiaries of the trust), with a requirement to act impartially with respect to Brian and Claire's respective interests in the trust.

As a financial advisor, however, Aaron has a fiduciary duty only to Brian (Aaron's client), with no such duty to Claire (who is not a client).

The trust owns the family home of Brian and Claire's deceased parents. Both Brian and Claire would like to have the home for themselves, but there's only one home, and the siblings have no interest in splitting it. In this case, Aaron's fiduciary duty as an advisor to act in Brian's best interests would motivate him to work toward the outcome that Brian wants – which conflicts with Aaron's duty as a trustee to act impartially toward both of the trust's beneficiaries and find a solution that would be equitable to both parties.

When a trustee's fiduciary duty to the trust beneficiaries conflicts with their fiduciary duty to their clients as an advisor, the advisor could risk being sued by the trust beneficiaries or their client if one believes the trustee/advisor placed the other's interests above their own.

Before accepting a role as trustee for a client's trust, then, financial advisors need to carefully review the trust document to understand who the beneficiaries are and whether any conflicts exist with the advisor's existing fiduciary duty to their clients. In some cases, the trust can be amended to resolve the fiduciary conflict – for example, by adding a co-trustee who must approve any transactions or distributions of trust assets. If that isn't possible, the advisor may need to decline or resign the trustee role, since neither trust law nor advisor regulations allow fiduciary duties to be waived by the party to whom they are owed.

Acting As A Trustee Triggers Custody Of Client Assets

Another major issue created by an advisor serving as a trustee for a client is that, in most cases, it will cause the RIA be treated by regulators as having custody over client assets. As described earlier, trustees often have a great deal of discretional power over trust assets, including the ability to make distributions and write checks on behalf of the trust. Trustees hold legal title to assets owned by the trust, and in both a legal and functional sense, trust property is effectively 'theirs'. Thus, even though the trustee may be restricted in what they can do with the trust property by the terms of the trust and their fiduciary duty to the beneficiaries, there is generally enough leeway to direct trust assets as they see fit – and consequently the opportunity for misuse – for the SEC and state regulators to treat the advisor as having total control over the trust and its assets.

The main implication of having custody over trust assets due to serving as a trustee is that it triggers the requirement for annual 'surprise' examinations by a third-party auditor under SEC Rule 206(4)-2. These examinations must be conducted at least annually on all client assets over which the advisor has custody, and they are done at the expense of the RIA. The silver lining is that if an advisor has custody over only a small number of client accounts, the examinations apply only to that relatively small subset of assets. However, the expense and hassle of needing to do any surprise examination, even if only on a few client accounts, may be enough to deter many advisors from serving as trustees for clients at all.

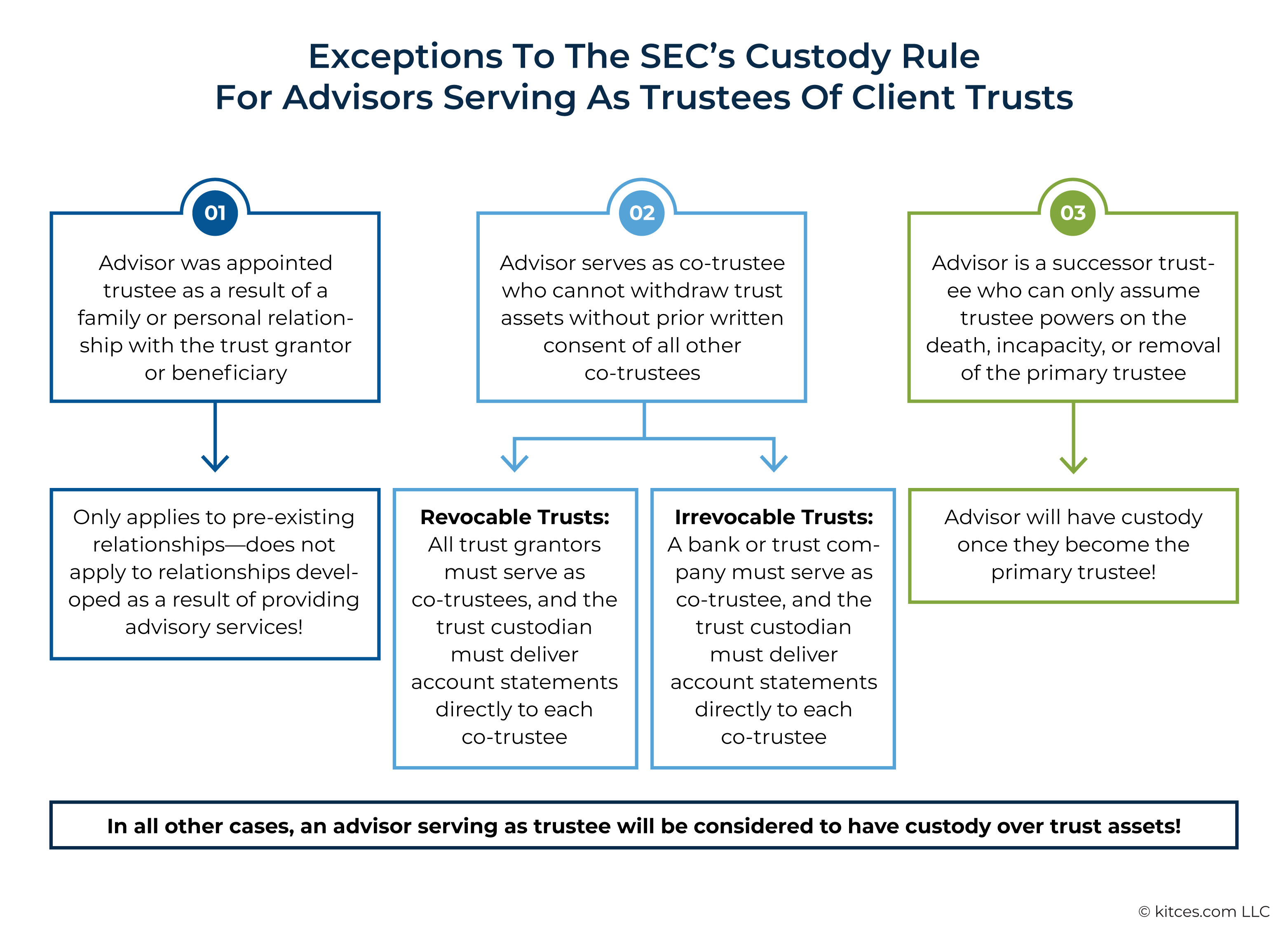

There are two exceptions to the blanket treatment of advisors serving as trustees as having custody over client assets, as laid out in the SEC staff's Q&A regarding the Custody Rule. First, advisors can serve as trustees of trusts whose grantors and/or beneficiaries are relatives of or have some other pre-existing relationship with the advisor, even if those parties are also clients of the advisor. (Notably, a personal relationship that develops as a result of the advisor's professional services – for example, an advisor and client who become close friends after many years of working together – does not qualify for this exception!)

Second, advisors can avoid having custody if, rather than serving as a sole trustee with the power to control and withdraw trust assets on their own, they serve alongside a co-trustee who must approve all withdrawals from the trust. There are two separate rules governing these situations, depending on whether the trust is a revocable (i.e., grantor) or an irrevocable (i.e., non-grantor) trust:

- For revocable trusts, advisors can avoid custody as long as 1) the advisor is prohibited from withdrawing any assets from the trust without the prior written consent of all co-trustees; 2) each grantor who has contributed to the trust acts as a co-trustee (along with the advisor); and 3) the trust custodian delivers account statements directly to each co-trustee.

- For irrevocable trusts, custody doesn't apply if 1) a co-trustee is a bank or trust company that meets the SEC's definition of a qualified custodian under Rule 206(4)-2; 2) the qualified custodian delivers account statements directly to each of the other trustees; and 3) any withdrawal of trust assets by the advisor requires the prior written consent of all co-trustees.

Additionally, being named as a successor trustee of a client trust – that is, agreeing to become the primary trustee if the trust's original trustee becomes incapacitated, dies, resigns, or is removed – generally won't trigger custody over trust assets, since the successor trustee typically doesn't have any power to withdrawal trust assets until they become the primary trustee.

For example, a client could serve as trustee over their own revocable living trust while naming the advisor as the successor trustee to take over as the primary trustee upon the client's death. This arrangement would not trigger custody for the advisor as long as the client remains alive. However, if the client passes away, and the advisor accepts and begins fulfilling the duties of the primary trustee, custody over the trust's assets is triggered, and the advisor becomes subject to the surprise examination requirement for those assets.

If an advisor agrees to be named as a client's successor trustee – such as when the client has no close relatives or friends to name – they need to plan for how to begin complying with custody requirements if the client passes away and the advisor becomes the primary trustee. Ignoring these requirements until after custody is actually triggered (i.e., after the client's death) can create serious complications, as there will already be enough work for the advisor to do in fulfilling their duties as trustee – retitling assets, paying funeral, medical, and administrative expenses, accounting for trust income and expenses, and managing transfers to beneficiaries – without the additional complication of figuring out how to comply with the custody rules that kick in as soon as the advisor accepts the role of primary trustee.

As shown below, while there are exceptions to the SEC's custody rule for advisors serving as trustees for their clients, in practice those exceptions are narrow in scope and limit the advisor's ability to exercise full discretionary powers over trust assets.

Additional Requirements For Broker-Dealer Representatives

In addition to the ethical and custodial considerations for RIA advisors serving as trustees, there is an additional layer of requirements for registered representatives of broker-dealers who serve as trustees for clients. Under FINRA Rule 3421, broker-dealer representatives who are named as a trustee of a client's trust must request and receive written permission from their broker-dealer firm before accepting the position. (The rule also applies to advisors who are named to other positions of trust, including executor of a client's estate or power of attorney, as well as to those named as a beneficiary of a client's estate.)

Under the same rule, broker-dealer firms must also establish procedures to reasonably assess the risk of representatives serving in those capacities, determine whether or not to approve the representative's request, and (if the representative is approved to serve as trustee) to supervise the representative to ensure they are complying with any restrictions that the firm imposes on the representative's trustee duties. The rule applies only when an individual representative is personally named as trustee of a client's trust – not when the representative's broker-dealer firm or an affiliate (e.g., the broker-dealer's own corporate trustee service) is named.

FINRA's Regulatory Notice 2020-38 lays out the ethical reasoning behind these requirements. Namely, financial advisors, acting in a position of trust, can have a great deal of influence over the financial decisions of their clients. An unethical advisor could, hypothetically, persuade their client to name them as the client's trustee, leveraging their trusted position to reassure the client that they will use those powers responsibly and act according to the client's wishes. Then, the hypothetical unethical advisor could take all manner of abusive actions to benefit from the trust themselves – from investing in high-commission financial products that don't serve the client's wishes to funneling funds into the advisor's affiliated business ventures to (in the extreme) outright stealing trust assets. The risks are particularly high for elderly or cognitively challenged clients, where abuse might not be noticed by family members or loved ones until after the damage has been done.

While most advisors would never abuse their position of trust in this way, the possibility is nonetheless left open when an advisor acts as their client's trustee. FINRA's rule – along with the SEC's custody treatment – aims to reduce that risk by putting a more watchful eye on those who serve as trustees for their clients' trusts. But the rule also limits the advisor's autonomy in deciding whether to serve. Broker-dealer firms may determine that there's too much liability risk in allowing their representatives to act as trustees for their clients, and/or that the cost of creating and enforcing supervisory policies is too high and may simply decide not to give permission to any representatives to act as trustees. In such cases, the advisor has little choice in the matter, since without the broker-dealer's permission, serving as a client's trustee would violate FINRA's rule.

Ethically Handling Client Trustee Requests: Either Don't Serve At All, Or Commit To Professionalized Trustee Services

With all the risks involved in serving as a trustee for a client – from ethical conflicts to custody issues to FINRA's rule requiring the permission of the broker-dealer – it can be hard to justify accepting a role of trustee for a client on a one-off basis. There are too many ethical barriers to navigate, too much expense in hiring an outside auditor to examine the assets over which the advisor is deemed to have custody, and, on top of all that, the risk that a beneficiary unhappy with one of the advisor/trustee's decisions could bring the matter to court, which likely wouldn't be covered by the advisor's professional Errors and Omissions (E&O) insurance.

The only exception might be for a relative or close friend who also happens to be a client of the advisor, where the custody trigger might not apply. Even then, the advisor would still need to be aware of potential conflicts of interest (e.g., due to their compensation as advisor and/or manager of the trust funds) and be prepared to demonstrate that those conflicts do not affect their decisions as trustee.

In most other cases, advisors would be better off declining the appointment as trustee, explaining to the client that the ethical conflicts between the advisor's role as investment manager and the discretionary power over trust assets make it best to avoid having one person in both roles. The client could instead name another trusted person as trustee or be referred to an attorney or corporate trustee with professional experience in trust administration – and with the liability protection necessary to be financially accountable for the service they provide.

The other option, however, is for an advisor to lean in the opposite direction and offer a fully professionalized trustee service as a separate service. This approach could make sense for advisors who serve many clients in situations where a trustee is often needed – for example, widows or unmarried individuals without a spouse to name as trustee. As more advisory firms seek to differentiate themselves by offering an expanded variety of services (most commonly tax preparation, but also others like cash management, bill paying, and estate documents), trust administration could be considered another ' high-touch' service that helps an advisor stand out to higher net-worth clients.

Although offering trustee services would trigger the SEC's custody rule and require annual audits of the trust accounts for which the advisor serves as trustee – which could be costly, as the advisor must cover the expense of the third-party auditor's examination themselves – it could be worthwhile in two ways.

One approach is for the advisor to be compensated for serving as trustee. Trustees are generally allowed to receive reasonable compensation for their work administering the trust, considering the value of the trust, the nature of the duties involved, and the trustee's skill and experience in performing the role. A set fee schedule for trustee services could, on its own, offset the additional expense of custody compliance and annual audits. The advisor could choose to offer a bundled fee for trust administration and asset management (as many corporate trustees do), or charge both fees separately. In either case, the aggregate fees should be reasonable and justifiable for the services offered to avoid being challenged by beneficiaries.

Alternatively, offering trustee services can make up for its cost in a more indirect way if it attracts higher-net-worth, higher-fee-paying clients. In this framing, offering trustee services is not just a value-add or a convenient service to offer to clients, but an intentional business strategy for serving the types of clients who might prefer a one-stop shop for both administering a trust and managing its assets. Families with a trust-based estate plan are typically at least moderately affluent, and many are likely to value working with a professional who can make wise decisions regarding both the administration of the trust itself and the way its assets are invested. Such clients may be willing to pay a premium to a professional who can offer both of these attributes, making the cost and complexity of custody compliance a potential investment into a business strategy that will pay higher returns in the long run.

But the main point is that, if a client asks an advisor to serve as their trustee, in almost all cases (except for close family and friends), it's best for advisors to decline the request – unless the advisor has an intentional business strategy to offer professionalized trust services along with the underlying systems and support structures to handle it.

How To Structure A Trustee Service Offering

If an advisor decides to offer trustee services as a part of their business model, there are three key questions to address.

First and foremost, which clients will the advisor serve as trustee for? Will they accept trustee appointments only for certain clients (e.g., those who meet specific criteria)? Will they make the decision based on quantitative factors (such as client net worth or trust assets) or qualitative factors (such as client interviews or the types of assets in the trust)? Advisors should be cautious about whom they decide to serve, since a mismatch between the advisor's expertise and the nature of the trust assets can create fiduciary challenges. For example, if a trust's property is mainly made up of real estate and the advisor isn't a real estate expert, fulfilling their fiduciary duties to the trust's beneficiaries in managing the trust and maintaining its property may prove difficult.

Second, how will the advisor manage liability risk? At a minimum, they may need to add a rider to their E&O insurance policy or add a separate policy to protect against the financial liability of being sued by a beneficiary. Decisions made by the trustee can always be challenged by a beneficiary in court. And while that may seem unlikely at first glance, it's worth remembering that while the client who originally asked the advisor to serve as trustee may have had a close and trusting relationship with the advisor, the same may not be true of the trust's beneficiaries. Even if the advisor makes a sound and objectively correct decision (e.g., declining a beneficiary's request for a distribution to buy a sports car when the trust only provides for distributions for health, education, maintenance, and support), unhappy beneficiaries may still try to challenge the decision or even attempt to remove the advisor as trustee, and the legal expense of defending challenges can be substantial. A well-structured liability policy can help cover those costs for advisors acting both as trustee and as financial advisor. Additionally, advisors may consider forming a separate business entity – like an LLC or S corporation – to handle trustee work and protect the assets of the advisory firm itself.

Finally, what processes will the advisor need to have in place to fulfill the day-to-day duties of a trustee? Will they engage an accounting firm to prepare the annual tax returns each trust must file? How will they ensure that they meet trust reporting requirements, such as providing each beneficiary with annual reports or account statements? How will they maintain clear, proactive communication with beneficiaries to avoid misunderstandings and distrust – two of the most common reasons for legal disputes between beneficiaries and trustees?

There's no single good answer to any of these questions, but they're all worth considering before an advisor accepts a trustee role. Having systems, policies, and support structures in place ahead of time ensures the advisor can carry out their fiduciary responsibilities effectively – rather than figuring it all out on the fly.

For advisors, being asked to serve as trustee is a powerful reminder of how much trust clients place in them. Most people would ask few individuals outside their circle of closest friends and immediate family to take on the responsibility of caring for their assets after they pass, and it's a testament to the depth of relationship that advisors develop with their clients that they are often asked to fulfill that role themselves.

But it's precisely because of that trust – and the weight that the trustee role carries – that most advisors should hesitate before agreeing. Will they be able to manage the additional duties of trustee on top of their role as a financial advisor and ensure the proper safeguards are in place to fulfill their dual fiduciary duties to clients and to trust beneficiaries? Does their compensation cause any conflicts of interest that could expose them to challenges from the trust's beneficiaries, even when trying to do the right thing? Can they absorb the cost and administrative burden of having custody over client assets, even if it's 'just' the assets in the trusts they oversee? And do they have the structures and liability protection needed to perform their role effectively, consistently, and accountably?

Ultimately, for advisors who take a thoughtful approach to answering these questions and decide to include trustee services as part of their offering to clients, doing so can have the dual benefit of strengthening the business case for serving high-net-worth clients and building a structured process that makes it easier for the advisor/trustee to fulfill their dual role. And for those who prefer not to build out an entire trustee offering, taking the time to vet corporate trustees or attorneys can still ensure clients have the peace of mind that their wishes will be carried out faithfully once they're gone.