Executive Summary

Hiring a new employee brings the promise of delegation and an increase to the hiring advisor's individual capacity. Yet despite the promise that hiring offers, many firms struggle to see a meaningful lift from new team members. What often appears to be an onboarding issue – slow ramp-up, mismatched expectations, or underperformance – is more accurately a hiring issue. In an industry where talent is scarce and the cost of a bad hire is high, selecting the right person for the right role is one of the most strategic decisions an advisory firm can make. And counterintuitively, long-term growth may depend not on hiring someone like the advisor, but someone fundamentally different.

In this article, Sydney Squires, Senior Financial Planning Nerd, describes the potential pitfalls of hiring someone too much like themselves and how to ensure that the new hire is inclined toward their role – most often, by hiring their opposite.

Employees who are too similar in aptitude to their manager often gravitate toward the same work, leaving essential but unappealing tasks untouched. This can lead to one of three unsatisfactory outcomes: the advisor ends up keeping the tasks they intended to offload, an additional hire is made prematurely to handle the gap, or the new employee exits due to misalignment – all of which reduce efficiency and hurt firm profitability. Instead, sustainable delegation and firm growth come from hiring someone whose strengths and interests are the advisor's weaknesses. This strategy increases the likelihood that the new hire will not only accept the delegated work but also take ownership of it and improve it over time.

To maximize hiring effectiveness, tools like the Working Genius framework offer a structured way to assess candidates' natural inclinations and identify how their strengths map to the job responsibilities. By first determining which tasks need to be delegated, then identifying the personality traits and aptitudes needed to perform them well, managers can attract candidates whose native genius aligns with the firm's operational gaps. This increases not only the likelihood of long-term retention but also the odds that the employee will innovate and streamline processes that previously stalled firm growth.

When interviewing for a role, asking questions about the candidates' favorite work and what they enjoy can also be instructive. Someone who loves brainstorming and big picture work may struggle with a role that is solely checklist-oriented – and vice versa. Working Genius or other assessments can articulate a candidate's potential strengths in a structured, relatively unbiased way.

Ultimately, delegating to someone who finds joy and energy in tasks the manager finds draining not only boosts morale but leads to more effective execution and even innovation. Over time, this symbiotic dynamic allows the advisor to redirect focus toward higher-impact activities like business development, while empowering the new hire to refine processes and assume greater responsibility. When hiring decisions are driven by strategic self-awareness and intentional role design, advisors unlock a virtuous cycle of trust, delegation, and growth. The result is not only a more efficient firm, but a more fulfilled team – and a founder who can spend more time in their own zone of genius, building the business they envisioned in the first place!

A new hire represents an exciting chapter for an advisory firm. According to Kitces Research on How Financial Advisors Actually Do Financial Planning, adding team members is the main driver available to firms to increase team productivity. It is hard to overstate how important hiring team members that the advisor can delegate to is to firm growth. It's a part of why (beyond the immense satisfaction that comes with building a team of people who are dedicated to the firm's vision) advisors endure the work of crafting and listing the job position, interviewing candidates, creating and grading work samples, negotiating salary and benefits, and designing and implementing an onboarding plan.

However, there is one important asterisk to these gains: hiring team members doesn't in itself provide the firm with any benefits. In fact, the first year of a new hire is often spent training, giving context, explaining strategy, and providing feedback to the new employee. It takes time for the advisor-turned-manager to truly delegate their work and begin to reap the bottom-line rewards of a new hire.

Nerd Note:

The term "manager" here is being used as an umbrella term. Often, especially in small advisory firms, the founder is also functioning as lead advisor, the manager, and in a few more jobs besides, and is used primarily to distinguish them from those who report to the manager (or are applying for the job).

While most new hires can operate independently in their day-to-day tasks, it often takes six months for them to internalize the firm's strategies and long-term goals. Furthermore, it can take a full calendar year for an employee to 'see' everything the firm does, as many tasks are only performed on an annual basis.

However, if an employee leaves the firm, most of this progress is lost. All of that delegated work either returns to the manager, gets shared amongst the rest of the team, or is set aside until capacity grows. In any case, this creates additional strain as current or future projects are ignored or delayed in order to start over with the interviewing… and hiring… and onboarding… and training.

In other words, hiring alone does not improve firm outcomes. Instead, hiring and retaining employees is the key to increasing the firm's long-term growth.

And while employee retention is not entirely within the firm's control, the hiring team can maximize their chances by hiring someone who truly fits the responsibilities of the role, rather than someone who is simply a cultural fit, or who mirrors existing skills on the team.

The Business Challenges Of Hiring For Familiarity

A new hire can go awry for a variety of reasons, and it can be difficult to evaluate what specifically went wrong. For instance, did a new hire leave due to a poor cultural fit, a lack of a robust onboarding plan, or something else entirely? One problem that can lead to a bad-fit hire is a mismatch between the new employee's skills and interests and the actual work the firm needs to be done. This scenario often manifests when the hiring team doesn't clearly define what tasks the new role will be responsible for. Instead, they default to hiring someone similar to themselves – whether out of a sense of familiarity or a desire to boost up someone whom they see themselves in.

An advisor could rationalize this approach as follows: "I need someone to take these tasks I've held for years, and I need someone to help grow this firm – an employee, yes, but also someone who I can think and strategize with." Thus, many managers are inclined to hire someone similar to themselves. In fact, they may even think, "I want to give a 'mini-me' the opportunity I would have wanted five years ago".

However, while hiring, for instance, an associate advisor who is inclined like the owner may be satisfying in the short-term, it introduces significant risks. The manager themselves (likely) didn't aspire to become a long-term associate advisor at a budding firm. They likely grew toward the lead advisor role in part to avoid the tasks that they didn't enjoy (which is why they became an amazing advisor… and not an amazing CSA). Five years ago, the manager was probably thinking about how to start their own business, not how to perform support tasks!

How A Too-Similar Hire Can Go Wrong

Of course, the majority of hiring managers want their new employee to be a fit. It can be tempting for the manager to figure that they enjoy their workplace and therefore seek someone who is similar to them in inclination (if not in work experience). However, hiring someone who is too similar in aptitude and inclination to their manager risks creating serious blind spots or redundancies in the long run.

To start, team members with the same aptitudes and personality as their managers are likely to enjoy (and ask for) tasks the manager also enjoys and excels at. The manager's feeling of responsibility for their employees' wellbeing, enjoyment of their day-to-day work, and success is laudable. But if the manager and team members want to do the same work, then some combination of three outcomes inevitably emerge.

First, the manager delegates work they enjoy and keeps work they don't. Despite the fact that they hired a new employee in large part to delegate tasks they don't enjoy (or that are a poor use of their value to the firm), this obviously suboptimal business practice is actually fairly common. Delegation is crucial to moving the firm forward – managers need the ability to focus their time on business development or strategy in order to continue developing the firm. And with every new hire, more growth is needed to maintain firm revenue margins and continue to grow the team, so the opportunity cost of keeping lower-value tasks continues to grow.

Second, if the new employee doesn't want to take on the delegated tasks, and the manager doesn't keep them, it's likely that an additional person is hired (full-time or as a contractor) earlier than planned. A common version of this story is a lead advisor hires an associate advisor, then realizes they actually needed was a CSA or paraplanner. Hiring an additional person too early can affect short-term cash flow and add additional pressure on the business to grow quickly.

The final possible outcome is that the new hire does not have a long-term place on the team. If the senior advisor does not want to maintain certain tasks, and the new hire doesn't want to do them… well, the math is easy, but that conversation is not. This route is the most difficult in the short-term but may be the most merciful in the long-term – both to the manager and employee.

None of these three options are mutually exclusive; in fact, many of them overlap. The manager is often stretched between three interests: theirs, their team's, and the firm's. When these interests are aligned, it can feel like magic; when these interests are in opposition, simply getting through a workweek can become a Sisyphean task as managers struggle to get a true lift from hiring.

Bad Fits Are Clear, Quickly

While the experience of a bad-fit new hire can unfold in different ways, the lack of fit itself typically becomes clear to everyone within just a few weeks of onboarding. The initial evidence of a bad fit often appears in two ways. First, the new employee may not fully understand their tasks, the firm's mission, or why things are done in a certain way, despite the training and infrastructure provided. This often manifests as an 'off-pace' onboarding plan. Second, the new hire may immediately chafe against the tasks (even if they understand them). This is more common with 'mini-me' hires because that they don't want to do their role – they likely want to do a role more similar to the manager's.

Either outcome is frustrating for both the new employee and their manager, who likely both want this role to work. The natural response is to pour more time into onboarding or to adjust the role to better fit the new hire. The unfortunate truth is that if the 'wrong' person was hired, then the best onboarding process in the world won't fix a fundamentally incompatible role. Instead of hiring someone with very similar traits, the better bet is to hire someone with the opposite traits who wants to take on the work that is less satisfying (and potentially less profitable) to the manager.

So, What Does A Good Fit Look Like?

How can hiring managers avoid the temptation to hire based on familiarity, and instead onboard employees that truly fit? Evidence shows that compatibility between the firm, the role, and the employee is crucial to a long-term mutual fit. For example, Kitces Research on What Actually Contributes To Advisor Wellbeing found that advisors who self-reported as 'very satisfied' with their work shared four key perceptions of their job:

- Identity: I can be myself at work

- Autonomy: I structure my schedule to work best

- Competence: I am effective at my job

- Purpose: What I do in my work life is valuable

Advisors who scored highly on these four components were more likely to be thriving (defined as having self-reported wellbeing levels of 9 out of 10 or higher). 86% of these thriving advisors reported that they were extremely likely to stay at their advisory firm. On the other hand, advisors who were struggling (with self-reported levels of wellbeing at 5 or below), rarely shared the same view. Only 52% of struggling advisors planned to stay at their current firm; 9% of them reported that they were extremely likely to leave their current role in the next year.

In other words, these four perceptions of work have very real consequences in both short-term satisfaction and long-term employment.

Right Person/Right Seat

The incredible lift of a high-fit, high-performing employee cannot be overstated. This is referred to as Right Person/Right Seat in the Entrepreneurial Operating System (EOS). The Right Person in the Right Seat (and, to take it a step further, in the Right Firm) has some level of intrinsic motivation that naturally aligns with the firm, the company culture, and their day-to-day work. This is explored further in the book "How To Be A Great Boss", by Gino Wickman and René Boer, which explains how to be a manager within EOS. Right Person / Right Seat is broken down into three core traits:

- Get it – have the aptitude, natural ability, and thorough understanding of the ins and outs of the job.

- Want it – sincerely desire the role.

- Have the Capacity to do it – possess the emotional, intellectual, physical, and time capacity to do the job.

By and large, EOS emphasizes intrinsic motivation as the key for an employee's success. Intrinsic motivation, backed by sufficient extrinsic support, makes the difference between a highly engaged employee and a 'standard' one, and is often the difference between a short- and long-term employee. However, notice that this description still includes an extrinsic support system, especially in Capacity. While Capacity has some intrinsic roots in a person's innate capabilities, as is described above, Capacity also involves the extrinsic combination of on-site training and support. A well-supported onboarding and support process builds on an employee's intrinsic traits to set them up for success.

Notice that in the Right Person/Right Seat framework, the new hire must have the capacity and desire to perform the specific role in question. Rather than only aiming for a match to the firm's culture, hiring managers must aim to find someone who fits the job to be done. So, when an advisory firm decides to hire, one of the biggest initial decisions is what type of person to hire, and the type of tasks this new hire could accomplish.

Building Complementary Skills Across Team Members

Kitces Research on How Financial Planners Actually Do Financial Planning indicates some of the risks that come from hiring too alike, especially for small firms. While a two-advisor team (with no support staff) yields more revenue per team member than a solo advisor, the increase in productivity is not commensurate with that of a "1+1" team (one advisor and one support staff). As shown in the graphic below, a team of one advisor, one support staff is 15% more productive than a two-advisor team with no dedicated support staff.

There are many dynamics at play behind revenue per team member, but one of the reasons that a "1+1" team has such a differentiated outcome on productivity than a "2+0" team is the power of differentiated skill sets. While a "2+0" team has overlapping skills, a "1+1" team has clearly defined, separate job responsibilities. Because an advisor cannot share advisor-specific responsibilities with their support staff, the advisor's sole option is to delegate work. This also prohibits advisors from making decisions that tend to inhibit the firm's revenue in the long-term, such as jointly servicing clients and retaining lower-revenue clients (for better and worse). A differentiated team is, on average, a team where the senior advisor is able to maximize client-facing time. Keeping in mind the power of differentiated skills can help a hiring manager better define the role they need to fill while also elevating the importance of complementary skills (and personalities!) over familiarity.

Why Hiring Your Opposite Can Help Unlock Long-Term Growth

While hiring a person who operates similarly to the manager can create potential issues in delegation and workflow, hiring someone who is the opposite of the manager makes delegation much easier.

Opposite-You Wants To Do Your Least Favorite Work

If a team has differentiated tasks, it follows that the team's personalities and aptitudes should be differentiated as well. An employee who is inclined toward a task that the manager doesn't want to do is more likely to take on the work in the first place. It makes a world of difference to delegate to someone who wants those tasks – and that can feel a little unfathomable to the manager who dislikes doing that work. And while mastering the art of delegation, it's normal to feel guilty giving all of this uninteresting, boring work to their direct report – but when the correct person is hired, those will actually be tasks they enjoy!

In her leadership strategy book "Multipliers", executive advisor Liz Wiseman defines the concept of "Native Genius": "[S]omething that people do, not only exceptionally well, but absolutely naturally. They do it easily (without extra effort) and freely (without condition). …They get results that are head-and shoulders above others, but they do it without breaking a sweat." In other words, the employee may do the delegated work better than the manager could, and in less time. This, in turn, creates a powerful cycle for the manager to delegate more responsibility. And, in the process of taking full ownership of the work, the employee may improve processes further.

In her leadership strategy book "Multipliers", executive advisor Liz Wiseman defines the concept of "Native Genius": "[S]omething that people do, not only exceptionally well, but absolutely naturally. They do it easily (without extra effort) and freely (without condition). …They get results that are head-and shoulders above others, but they do it without breaking a sweat." In other words, the employee may do the delegated work better than the manager could, and in less time. This, in turn, creates a powerful cycle for the manager to delegate more responsibility. And, in the process of taking full ownership of the work, the employee may improve processes further.

With Ownership Comes (Process) Improvement

When people work on tasks they genuinely find engaging, they often find ways to improve it by making things more efficient, building processes, or simply by raising the quality of the work. Often, they may think of things that the manager themselves may not have.

For example, many founding advisors are not process-oriented. The inclination toward ideation, wondering what is possible, and getting work done was crucial to building the firm, especially in the early days. However, as the advisory team grows, there is an increasing need for process, standards and organization.

The founder will likely have input in some areas of these processes and standards so that the brand and feeling of the firm don't change. However, if the not-process-oriented founder tries to crystallize the firm's core processes, create and document these steps, and communicate these changes to the team, this work would both take longer than needed and be a subpar product. Furthermore, time spent defining process is time the founder is not spending on high-value work they are uniquely inclined toward, such as business development. It is often faster to hire someone who is really inclined toward building processes that can extract this information from the founder and document it. This process-oriented person is more likely to enjoy that work and will do it better.

In the book "Who Not How", Dan Sullivan and Dr. Benjamin Hardy describe this effect as letting the "Who" (the person who specializes in this work) do the "How" (determine the processes involved to move it to completion): "If you're going to apply higher levels of teamwork in your life, you'll need to relinquish control over how things get done. Instead, you'll need to put your trust in capable Whos, giving them full permission to own their Hows. Only then will you get people's greatest work."

In the book "Who Not How", Dan Sullivan and Dr. Benjamin Hardy describe this effect as letting the "Who" (the person who specializes in this work) do the "How" (determine the processes involved to move it to completion): "If you're going to apply higher levels of teamwork in your life, you'll need to relinquish control over how things get done. Instead, you'll need to put your trust in capable Whos, giving them full permission to own their Hows. Only then will you get people's greatest work."

This framework only works if the employee both understands the vision of the firm and is fully bought in to how their specific work improves the firm. When someone is inclined toward the manager's weaknesses and is able to fill in those gaps, the advisor can delegate more tasks and spend more time with clients or developing the business. That, combined with the work that has been delegated (and hopefully improved on by the employee), means that the employee may have more opportunities to grow in responsibilities and compensation – all of which can play a part in the employee's long-term retention.

How To Hire Your Opposite – Who Still Sees Your Vision

There's a natural tension between these two goals: the manager needs someone who is a cultural fit and believes in the vision of the firm, yet that same person will likely have a different work style and set of strengths than the manager (in order to complement the manager's skill set). While finding the balance between this tension can be challenging, it can be done – and can yield a more competitive, relevant, and fruitful hiring process.

Clarify What Work Will Be Delegated

A good starting point for determining who to hire next starts with assessing the current composition and goals of the firm – what work needs to be delegated to this seat, and what potential personality types would thrive with that type of work? For example, if hiring a CSA, the manager may generally know what tasks this role is to fulfill, such as assisting on client communication and calendar management. It's also worth exploring opportunities to assign other work responsibilities that the manager (or other team members) don't enjoy.

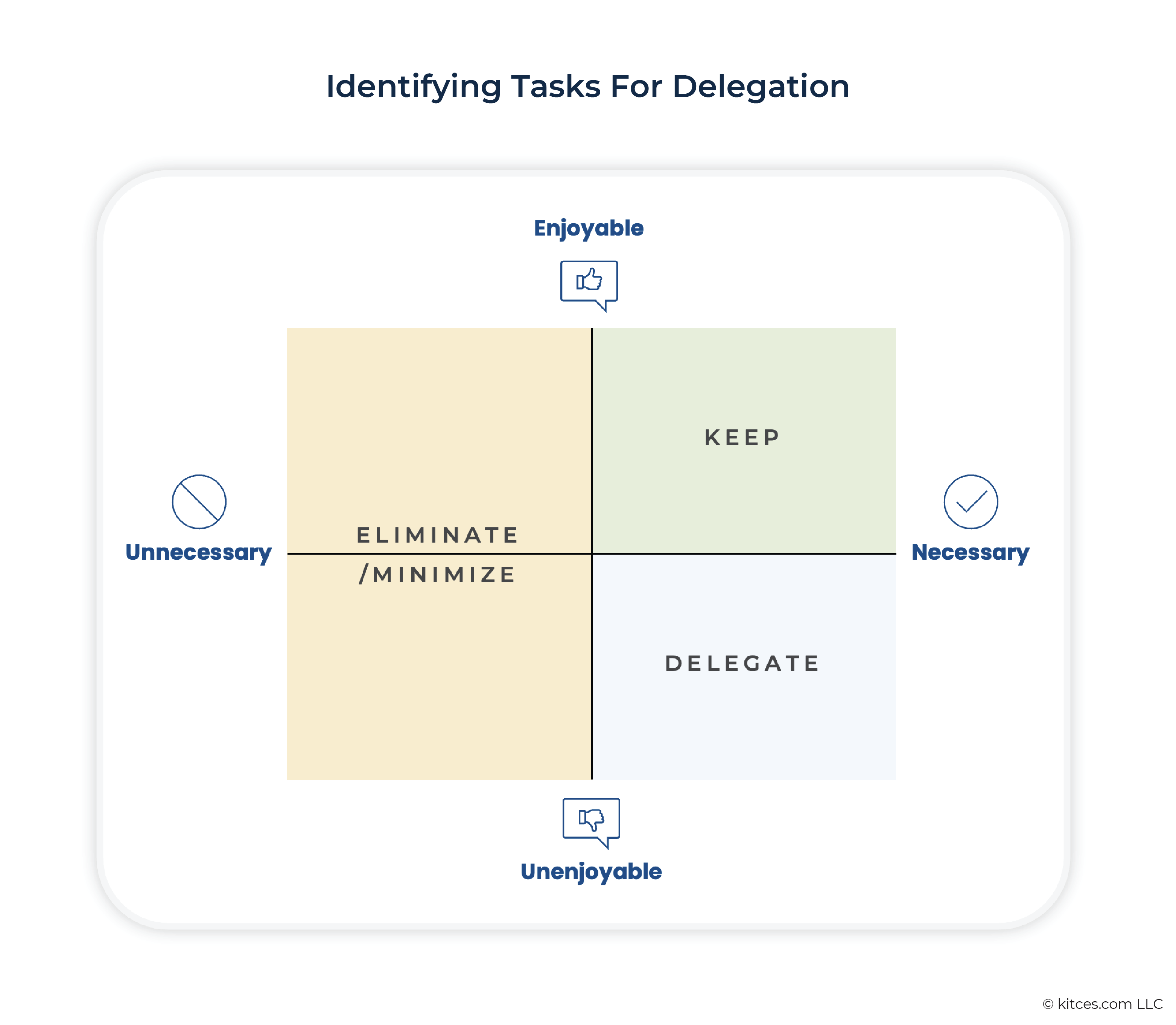

It can be insightful for the manager to start by examining their own workload, particularly when the advisory team is small. What work is necessary but unenjoyable? What work is necessary and enjoyable but takes too long relative to the manager's other responsibilities? What needs to be delegated in order for the advisor to spend their time on higher-value work?

Ultimately, delegation can be challenging – it's easy to feel like the prospective employee is getting a terrible, unenjoyable job. But tasks that feel draining to one person can be deeply satisfying to another, which means the conglomeration of unenjoyable (to the manager) responsibilities may, in fact, create someone else's dream job.

This doesn't mean a hiring manager throws every type of work conceivable into the job description, but some work tasks 'rhyme', naturally landing together, even if they're not traditionally associated with certain roles. For example, if the ideal prospective hire enjoys the gritty details of calendar management, are there data entry opportunities that require a similar mindset?

All of this can come together into an approximate list of job responsibilities, which can be broken into primary responsibilities (the main recurring tasks an employee will be evaluated on) and secondary tasks (less frequent but still important duties that need to be handled).

Determining Ideal Personality Traits For The Role

Once the job responsibilities have been defined, a hiring manager can next move on to identify the core traits an ideal candidate would possess.

After clarifying what work will be delegated, a psychometric assessment can be a powerful tool to create a standardized process that evaluates how well a candidate's strengths and personality align with position's key responsibilities. A good assessment has easy terms to understand, organizes strengths and weaknesses, and returns results that feel accurate to the person and their inclinations (no assessment is going to capture the full dimensions of a person, so something that feels 'mostly true' is a good starting point!).

One such assessment is Working Genius, a framework developed by Patrick Lencioni. Working Genius organizes work into six categories: Wonder, Invention, Discernment, Galvanizing, Enablement, and Tenacity. The assessment identifies two areas of Genius (tasks a person excels at and finds energizing), two areas of Competency (tasks they can perform well but don't necessarily enjoy), and two areas of Frustration (tasks they find draining and unfulfilling). Spending more time in 'Genius-related' work tends to foster happiness and fulfillment, while spending too much time in 'Frustration-related' work can make days feel longer, focus harder to maintain, and energy levels lower by the end of the day.

(Some people may feel that one of their competencies is really an area of Genius, that they have three Geniuses, or that one of their competencies is actually a Frustration, and that's okay! The purpose of Working Genius is simply to provide a framework for understanding how different types of work feel energizing or draining to different people.)

A brief overview of each area of Working Genius:

Wonder: The natural gift of pondering the possibility of greater potential and opportunity in a given situation. People with this Genius are constantly curious and on the lookout for what could be improved.

Invention: The natural gift of creating original and novel ideas and solutions. People who have it love to generate new ideas and solutions to problems and are comfortable coming up with something out of nothing.

Discernment: The natural gift of intuitively and instinctively evaluating ideas and situations. People with this Genius have a natural ability for evaluating or assessing a given idea or situation and providing guidance.

Galvanizing: The natural gift of rallying, inspiring and organizing others to take action. People who have it enjoy bringing energy and movement to an idea or decision.

Enablement: The natural gift of providing encouragement and assistance for an idea or project. People with this Genius are quick to respond to the needs of others by offering their cooperation and help with a project, program or effort.

Tenacity: The natural gift of pushing projects or tasks to completion to achieve results. People who have this Genius push for required standards of excellence and live to see the impact of their work.

Working Genius uses a trickle-down system: that is to say, it expresses the workflow as starting at the top (with Wonder and asking questions), then trickles downward through determining the best ideas and strategies (Discernment) and finally doing the work (Tenacity).

Mapping Working Genius To A Job Description

Working Genius (or the manager's assessment of choice) can be a great tool to review the job description. For example, is this going to be a client-facing or team-leading role? Will this work be largely heads-down and detail-oriented?

For example, a hiring manager may choose one Genius that the candidate must have to be considered, while also identifying the Frustrations that may be red flags. If the role focuses mostly on data entry, then a Genius in Tenacity may be helpful; conversely, if the role involves a lot of client-facing work, someone with a Genius in Enablement may find the work more fulfilling than someone with a Frustration in the same category.

If capacity is tight at the firm, it can feel challenging to narrow it down to 'just' one strength (if the job description needs all six areas of Genius, then the job description is too broad). This is where, again, focusing on complementary traits may be helpful. If everyone at the firm takes the assessment, and there are gaps in the areas of Genius, that may be an indication of what inclinations this new hire needs. For example, if no one in the firm has a Genius in Discernment, it may be helpful to add someone with that skill set (they may be inclined toward creating processes, narrowing down ideas, or other crucial roles!).

Broadcast Key Aptitudes And Traits In The Job Description

First, a general best practice for job descriptions: be explicit about the role's responsibilities, compensation, and the firm culture. Think of a job description as a filter: the goal is to maximize the number of viable candidates, which includes both attracting people who are a good fit and repelling those who are not. Different people are going to be attracted to different work environments, compensation amounts, and levels of intensity – so make it as obvious as possible for good fits to see that they are a fit.

To that end, within a job description, be certain to include a section on "Key Traits". Particularly for lower-level roles, focus less on experience required and more on the aptitude needed to succeed in the role. For example, is it more important for someone to be able to ideate, or that they follow processes precisely?

Generally, no more than four specific key traits are needed to properly define the aptitudes required for a role.

Interview For Aptitude And Evaluate Assessments

When candidates are being interviewed, be sure to ask questions that get deeper than work experience and relate to the candidate's aptitude. Some good questions to assess aptitude include:

- What was your favorite part of your previous job?

- What work makes you lose track of time?

- How do you tackle learning new data?

- What do you consider your greatest strength?

- Look over the job description. What about the job most excites you? What would you potentially change?

The candidate's responses will provide valuable hints regarding their potential fit for the role's responsibilities. Are they most excited by brainstorming sessions, but applying for a role where they 'just' need to follow processes and procedures? Are they someone who 'can't help' but analyze data? Where is there a natural fit in inclination, and where may there be some friction?

Use An Assessment To Get Data

Finally, while it is helpful to have candidates self-report, it is important that they take the assessment that is used by the firm. This is also helpful because in a job interview, the manager and the candidate are both aware that the manager is trying to assess the candidate, which, at times, can lead to a game of cat and mouse with the manager trying to get the 'real' answer and the candidate trying to give them the answer that they think the manager wants. The assessment itself can provide a more impartial view into a candidate's traits and strengths (though, of course, it is always worth asking the candidate afterward what they thought of their results!).

Generally, it's best to issue the assessment after eliminating some candidates through screening calls, both to reduce the number of tests paid for and to ensure that only the best candidates are getting the test.

Additionally, if work samples are a part of the review process, ensure that they align with the key traits being sought. If the job involves a lot of Discernment, such as determining the best tech vendors or building processes, be certain the work sample involves that area of Genius. (This may sound simple, but it's crucial).

By this point in the hiring process, the manager has a working understanding of the candidate's general inclinations – especially where they differ from the team. These differences can add a layer of nuance to the candidate's team fit and experience, helping the advisor to make a hiring decision that will allow them to truly delegate in the long run!

It's hard to overstate the lift that can come from hiring someone whose favorite work tasks are the ones that the manager most needs to let go of. When a candidate is hired who not only enjoys but also embraces the work, the manager may be pleasantly surprised by how much work they're able to delegate. And as the manager's workload shifts accordingly, they'll be able to focus their time on work that's more profitable for the business – and more fulfilling for themselves!

Leave a Reply