Executive Summary

Debt is an important tool in the financial toolbox, and can be very helpful when used in the right way. People often view 'good' debt in terms of loans that are subsidized and/or tax-deductible in some way, such as mortgages and Federal student loans. But some forms of debt can be useful for other planning purposes, such as when an individual needs a bridge loan to put a down payment on a new house while waiting for their old house to be sold, or if they have a large expense coming up like a home renovation or a new vehicle purchase and they want to avoid liquidating investment assets (and incurring capital gains taxes) to pay for it.

There are various types of loans available for these shorter-term borrowing needs, including Home Equity Lines of Credit (HELOCs) backed by the equity in one's home, and margin loans or Securities-Backed Lines of Credit (SBLOCs) secured by the value of the borrower's portfolio assets. While these loans offer some financial flexibility and have lower interest rates than other kinds of personal debt, like credit cards, they still tend to carry higher interest rates than the 'best' types of loans (e.g., mortgages and student loans). Moreover, interest paid on HELOCs, margin loans, and SBLOCs generally isn't tax-deductible, unless they're used for a small subset of purposes (e.g., a HELOC used for home renovations or a margin loan used to buy income-generating investment property).

In recent years, however, a new form of 'synthetic' lending has emerged as a potential alternative to margin loans or SBLOCs for short- and medium-term borrowing: The "box spread". At a high level, the box spread is an options strategy involving four different options contracts (selling a call, buying a put, buying a call, and selling a put), all with the same expiration date. The options contracts are structured so that, regardless of market movements, the 'borrower' is guaranteed to receive a net premium payment at the start of the period and to repay a fixed amount on the options' expiration date. Which makes the box spread effectively a zero-coupon loan where the 'principal', plus interest, is paid back at the end of the loan term. And owing to the fundamental math behind options pricing, the effective 'interest' rate paid on box spread loans tends to be only slightly higher than the interest on Treasury bills, which is far lower than the borrower would likely pay on a margin loan or SBLOC!

The tax treatment of box spread loans creates yet another advantage. Since a box spread effectively creates a net loss on a combination of options contracts, the 'interest' paid is tax-deductible as a capital loss. And because most box spreads qualify as 'non-equity options' under IRC Sec. 1256, a portion of the loan interest is usually deductible in each year that the box spread is in effect – even though the interest isn't actually paid until the options expire and the 'loan' is paid back. All of which means that in comparison to margin loans and SBLOCs, box spread loans have both a lower interest rate, and that interest is tax deductible (although box spread interest is only deductible against capital gains income, which is less of a benefit than being able to deduct against ordinary income – but it's still better than not being able to deduct the interest at all!).

Although options strategies are often risky, the offsetting 'legs' of a box spread mean that there's no inherent market risk from using a box spread – and because the Options Clearing Corporation (OCC) guarantees options contracts, there's very little risk that a counterparty will be unable to pay their portion of the options contract either. The main risk is that the amount to be repaid generally counts against the borrower's margin requirements in their brokerage account. Which means the borrower can borrow up to a certain percentage of the assets in their taxable account (typically 50%), and a severe market drop could trigger a margin call requiring the borrower to add more funds to their account and/or close out the box spread early.

The key point is that while box spreads won't necessarily replace advantageous debt like mortgages and student loans, their combination of low interest rates and tax deductibility can make them a viable alternative to HELOCs, margin loans, and SBLOCs in the shorter-term borrowing sphere. And with new providers starting to pop up that can handle the operational side of box spread borrowing and make it so that advisors don't need to manually construct box spread trades for their clients, they could become much more common in the years ahead as an option to meet clients' borrowing needs.

The Hierarchy Of Debt: Why All Loans Aren't Created Equal

Financial advisors spend a lot of time thinking about their clients' assets: their risk and return profiles, their liquidity, their tax characteristics, etc. But they don't always put as much focus on the debt side of their clients' balance sheets. Liabilities, however, can vary just as much as assets from one type to the next, and a key component of financial planning is ensuring that the clients' debt 'portfolio' is just as aligned with their financial goals as their assets are.

Liabilities work in a hierarchical way. While it might be oversimplifying to say that there are 'good' and 'bad' types of debt, there are types of debt that are better or worse for certain purposes. For instance, there's a reason that people generally don't use their credit cards to buy houses: The fixed (and lower) interest rate, level payment schedule, and tax deductibility of interest payments on a standard home mortgage make it a much better option for a person taking on debt to buy a home. But at the same time, a home mortgage (or a home equity loan or HELOC) isn't necessarily the best option to finance, say, a car purchase, since auto dealers and credit unions typically offer better interest rates (and in the worst case, an auto loan doesn't put the borrower's home equity at risk to finance a quickly depreciating vehicle).

In general, however, the 'best' kind of debt tends to have one or more of the following characteristics, which allow borrowers to pay less in loan interest or principal under certain specified conditions:

- It's subsidized; i.e., the government or some other lender pays some of the interest and/or principal of the loan on the borrower's behalf (Federal student loans are the most common example of this, for which the government pays the borrower's interest on subsidized loans for them while they're still in school, and may offer forgiveness of the remaining loan principal after a certain number of years as in the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program);

- It's collateralized; i.e., it is secured by an asset of the borrower, which allows the lender to charge a lower interest rate since they can seize the collateral property if the borrower doesn't pay back the loan (this includes home and auto loans that are secured by the property they're used to purchase, as well as margin or security-based loans which are secured by the borrower's investment portfolio);

- It's tax-deductible; i.e., the interest payments can be deducted from the borrower's taxable income to lower their taxes (this includes mortgages and investment interest for borrowers who take itemized deductions, student loans for borrowers under certain income thresholds, loans used to purchase business or rental real estate property, and up to $10,000 of auto loan interest from 2025 through 2028 under OBBBA). Technically this is another form of subsidizing certain loans via the tax code, but it's common enough to split into its own category.

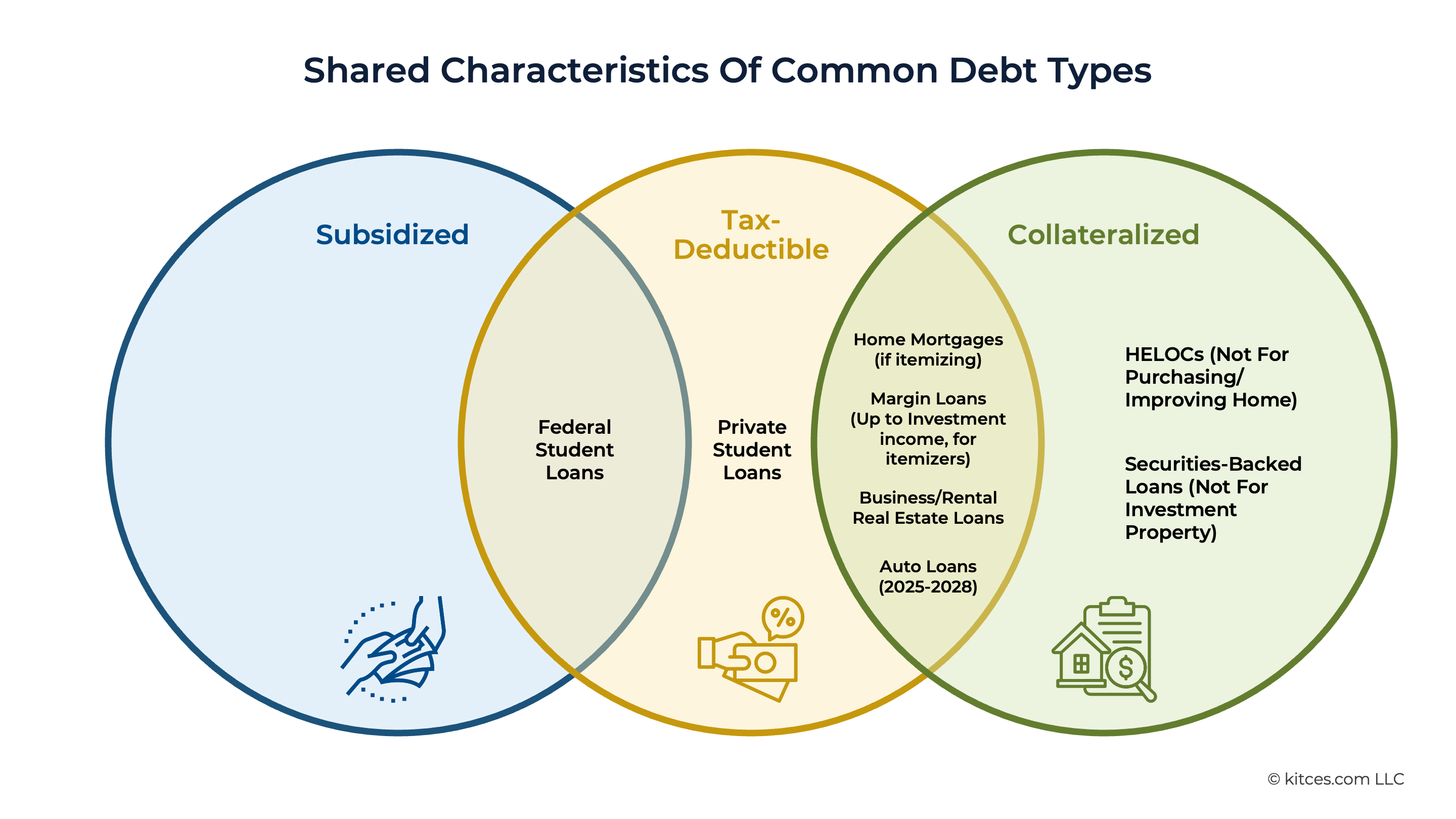

Certain types of loans, as shown below, share more than one of these characteristics. Federal student loans are both subsidized and tax-deductible, while home mortgages and margin loans for households taking itemized deductions, business and rental property loans, and qualified auto loans from 2025–2028 share tax-deductibility and collateralization. Other loans, meanwhile, may have only one of the characteristics above: Private student loan interest is tax-deductible but neither subsidized nor collateralized, while HELOCs not used to buy or improve a property and securities-backed loans not used to buy investment assets are collateralized but neither subsidized nor tax-deductible.

The more of these characteristics that one type of loan has, the better it is compared to other types of loans that might be available. Hence, collateralized and tax-deductible loans like home mortgages and business loans tend to be seen as the 'best' types of debt, along with subsidized and tax-deductible loans like Federal student loans. (There aren't any loans available that share all three characteristics of subsidization, tax-deductibility, and collateralization, although as noted above tax deductibility effectively serves as an indirect subsidy).

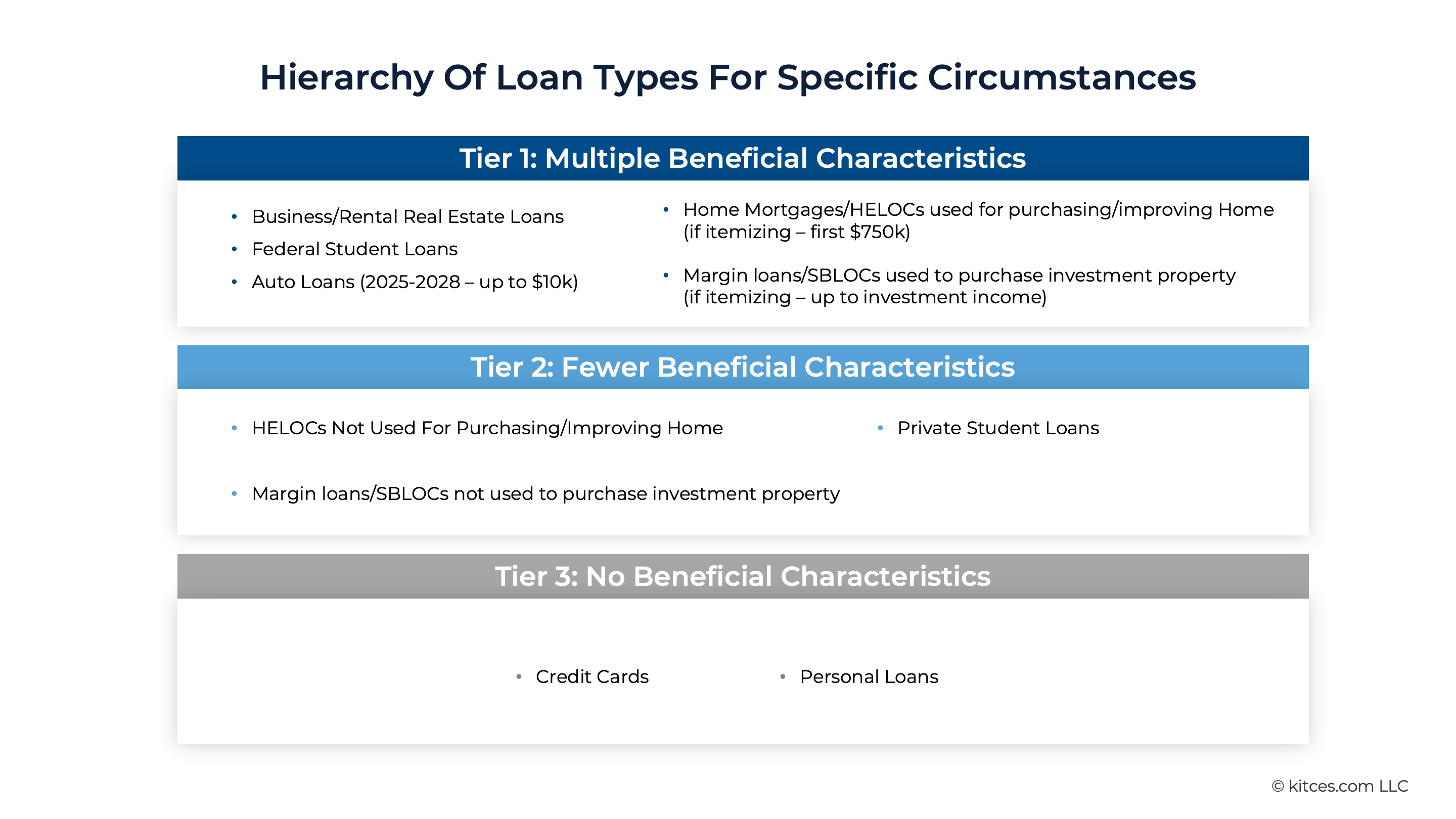

In other words, there's a hierarchy of loan types that can show, from top to bottom, the types of debt that a borrower should consider in certain situations, as shown below.

At the top are purpose-specific loans like business loans, mortgages, and Federal student loans, whose combinations of beneficial characteristics can result in the lowest effective interest rates. This usually makes them the first loan types to seek out in an applicable situation.

In the middle are private student loans, margin loans, and Security-Backed Lines of Credit (SBLOCs) used for general (non-income-producing) purposes, which have some – but not all – of the beneficial characteristics of the Tier 1 loans. These can serve as a backup option if a Tier 1 loan isn't available for a particular purpose. For instance, if an individual looking to purchase a new vehicle has income over the MAGI limits for deducting their auto loan interest, then they may want to consider using an SBLOC to finance the purchase instead of a standard auto loan, since that might have competitive interest rates plus a more flexible payment schedule than the auto loan.

And at the bottom are the loans with little or no benefit to the borrower: credit cards and personal loans. In both cases, these are generally uncollateralized and offer no subsidies or tax benefits. As a result, borrowers often pay significantly higher amounts of interest on these loans. They are often considered only as a last resort when none of the Tier 1 or Tier 2 loan types are available.

The key point is that the benefits of the 'best' types of loans are only available in certain circumstances and when used for specific purposes. For instance, when someone draws from a HELOC to pay for a home renovation, they can generally deduct the interest payments because the purpose of the loan was to improve their personal residence. But if they draw from the HELOC to pay for a new car, they can't deduct that interest (and they can't take the OBBBA auto loan deduction, since the loan must be secured by the vehicle to qualify).

The Role Of Portfolio-Backed Lending: Margin Loans And SBLOCs

For people with taxable portfolio assets to borrow against, portfolio-backed loans, such as margin loans and Securities-Based Lines of Credit (SBLOCs), are a common option for debt. As noted above, they fall generally in the middle of the hierarchy of loans, which means that they aren't necessarily the first type of loans that people consider when deciding how to finance, for example, a home or a college education, but they're often a good choice for other purposes.

Margin loans, which are generally made directly within an investor's brokerage account, are most often used to add leverage to a portfolio, i.e., to use the loan to purchase additional securities to enhance the rate of return or to hedge risk within the overall portfolio. SBLOCs are also backed by portfolio assets but are generally established separately from the account itself and, as a rule, cannot be used to purchase securities. Hence, they're often used similarly to HELOCs as a relatively short-term (5 years or less) source of financing. For example, if an individual needed a bridge loan to put a down payment on a new home while waiting for the sale of their old home to close, they might consider an SBLOC to provide that financing.

The problem with portfolio-backed loans is that, despite being collateralized loans, their interest rates can be high compared to other sources of credit (since the collateral involved consists of potentially volatile portfolio assets). For example, Schwab's current SBLOC rates range from 5.05% to 8.05%, with the rate decreasing the bigger the line of credit and the more assets that the borrower holds at Schwab. And margin loan rates tend to be even higher than SBLOCs, with Schwab's current rates ranging from 10.075% to 11.825%.

Moreover, unless the loan proceeds are used to buy income-producing investment property that qualifies for the investment interest deduction on Schedule A, the interest paid on portfolio-backed loans is generally not tax-deductible. So while a margin loan or an SBLOC might be a better option than a credit card for taking on short-term debt, they lack most of the advantages of the 'Tier 1' loans, like mortgages and Federal student loans.

Why Box Spreads Are A Good Alternative To Margin Loans And SBLOCs

In recent years, a new type of borrowing solution has arisen that can be a worthwhile alternative to SBLOCs and margin loans for individuals with portfolio assets to borrow against and the need for short-term financing: the 'box spread'.

Most lending today is done through traditional institutions, e.g., banks, credit unions, mortgage companies, student loan providers, and broker-dealer firms. But by using a carefully calibrated set of option contracts that expire all at the same time, it's also possible to create a 'synthetic' loan on the options market, which is the concept behind the box spread. Although box spreads can be operationally complex, their unique characteristics can result in very low interest rates – down near the rates paid on guaranteed government bonds – and can also generate a tax deduction on the interest paid. And new providers like SyntheticFi and Vest Synthetic Borrow have popped up to handle the operational complexity of box spread borrowing, making it much less cumbersome in practice.

So it's worth taking a deeper look at box spreads to understand how they work and when they can be a viable option for borrowing – particularly in comparison to similar forms of lending like margin loans and SBLOCs.

Mechanics Of Box Spreads

Though many advisors are familiar with the basics of options, it's key to understand how the buying and selling of put and call options work – and how they interact when combined together – to get an intuition of how box spreads can be used as a synthetic loan.

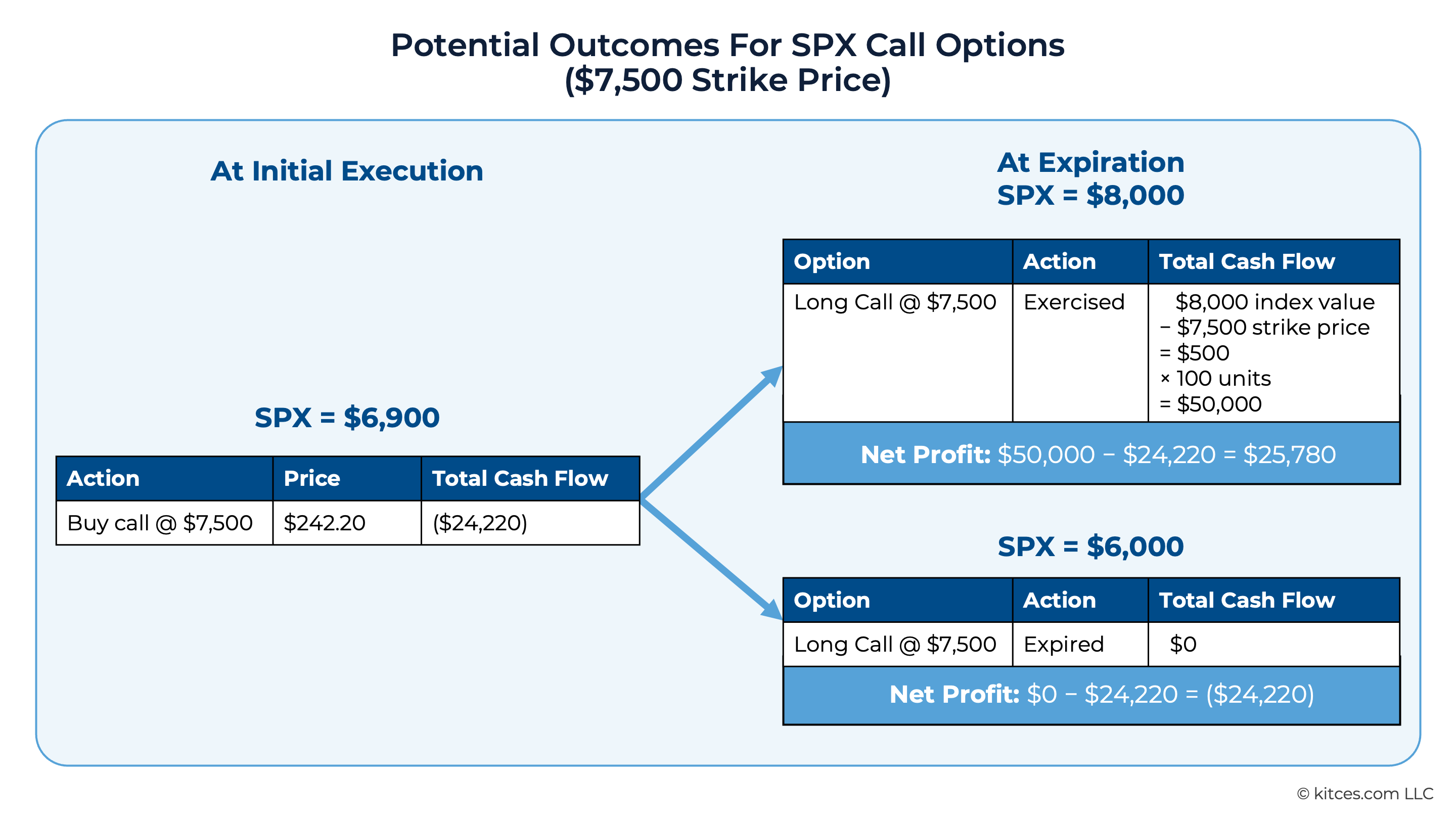

When an investor buys a call option, they pay a cash premium payment to the option seller in exchange for the right to buy an underlying security at a specific 'strike' price on the option's expiration date. Thus, if the security's price rises above the strike price, the option buyer gets to buy it at a discount to its market value, no matter how high the security's price rises. If the security's price is below the option's strike price at the expiration date, the option expires: the option buyer has already paid the premium to the seller, but no other money changes hands. And the 'security' on which the option is based can either be a specific actual security like shares of stock or an ETF (where the actual shares of the security are exchanged if the option is exercised) or an index like the S&P 500 (where only cash changes hands, in the amount of the value of the underlying index minus the strike price). Options contracts generally cover 100 shares of the underlying security (or units of the underlying index).

Example 1: Andrea buys a call option for the S&P 500 index (SPX) with an exercise price of $7,500 and an expiration date one year from today. She pays a premium of $242.20 per share, or $24,220 total.

If SPX is at $8,000 on the options' expiration date, Andrea can exercise the options and buy 100 units of SPX at $7,500, receiving 100 × ($8,000 − $7,500) = $50,000 in cash. Thus, she receives a net profit of $50,000 − $24,220 = $25,780 after accounting for the premium payment.

If SPX's value declines to $6,000 (or any value below $7,500) on the expiration date, however, the options will expire and Andrea will receive nothing (resulting in a net loss of $24,220 when accounting for the premium).

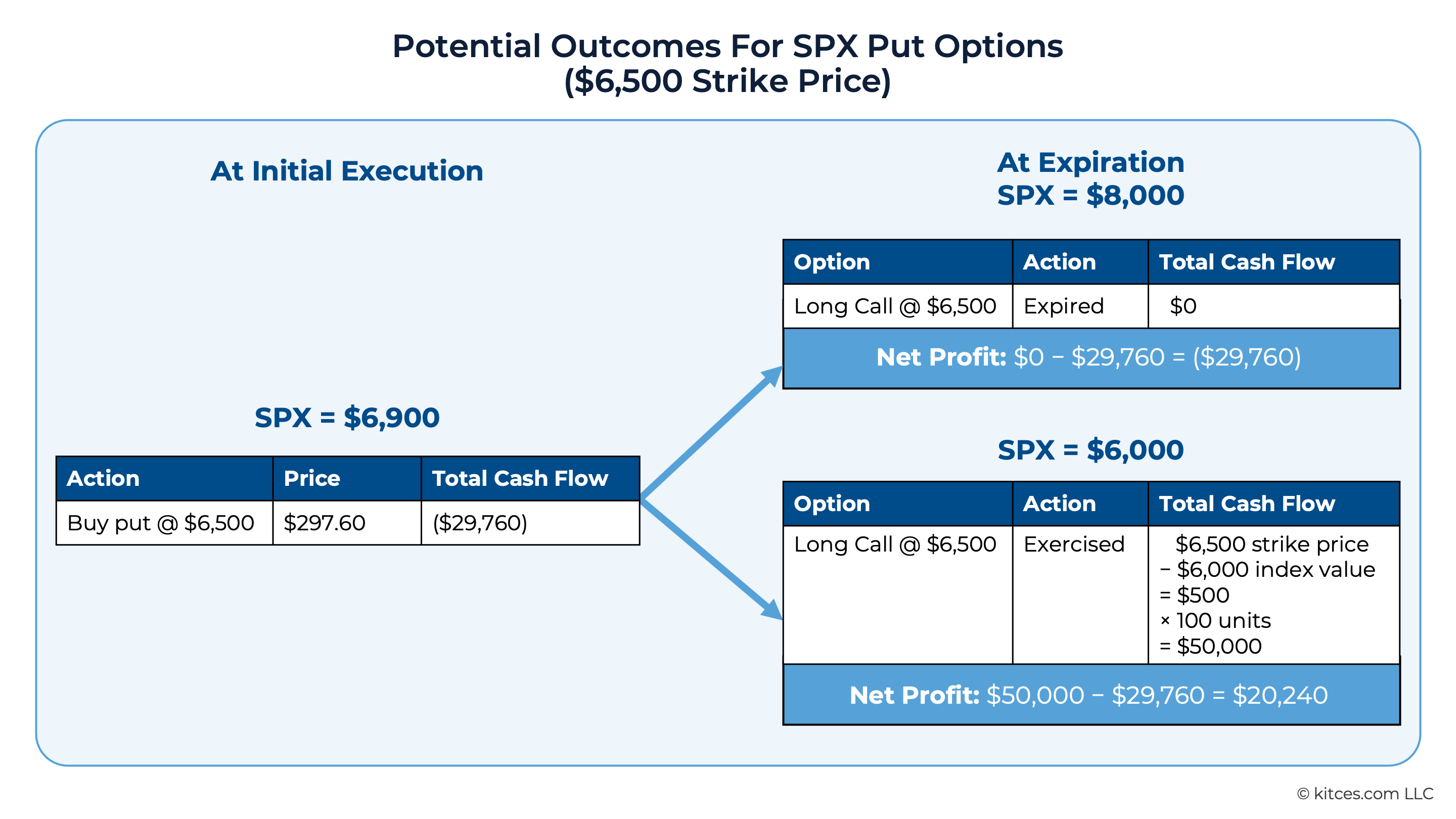

When an investor buys a put option, they pay a premium to the seller in exchange for the right to sell the underlying security or index at the strike price on the expiration date. In this case, if the security's price falls below the strike price by the expiration date, the buyer exercises the option and sells the security to the option seller at the strike price, no matter how much the security's price has fallen. And if the security's price stays above the option's strike price, the option expires with no other money being exchanged.

Example 2: Bethany buys a put option for 100 units of the S&P 500 (SPX) with an exercise price of $6,500 and an expiration date one year from today. She pays a premium of $297.60 per share, or $29,760 total.

If SPX increases to $8,000 when the options expire, the options will remain unexercised, and Bethany will receive nothing, realizing a net loss equal to the $29,760 premium she paid.

But if SPX instead declines to $6,000, Bethany can exercise the options and sell 100 units of SPX at the $6,500 strike price, getting 100 × ($6,500 − $6,000) = $50,000 in return (and a net profit of $50,000 − $29,760 = $20,240 after accounting for the option premium).

Nerd Note:

Options can either be sold as "American-style" where the option can be exercised at any point on or before its expiration date, or "European-style" where it can only be exercised on the expiration date itself. Box spreads always use European-style options in order to be guaranteed for a specific time period, so this article likewise focuses on European-style options.

While options can be bought and sold on a one-off basis, they can also be combined in various ways, both by buying (i.e., going long) and selling (i.e., going short) options to guarantee certain outcomes. For instance, by selling a call option and buying a put option with identical expiration dates and strike prices, an investor will sell the underlying security or index at the strike price regardless of its actual price on the expiration date: If it rises above the strike price, the call option will be exercised, and if it falls below the strike price, the put option will kick in.

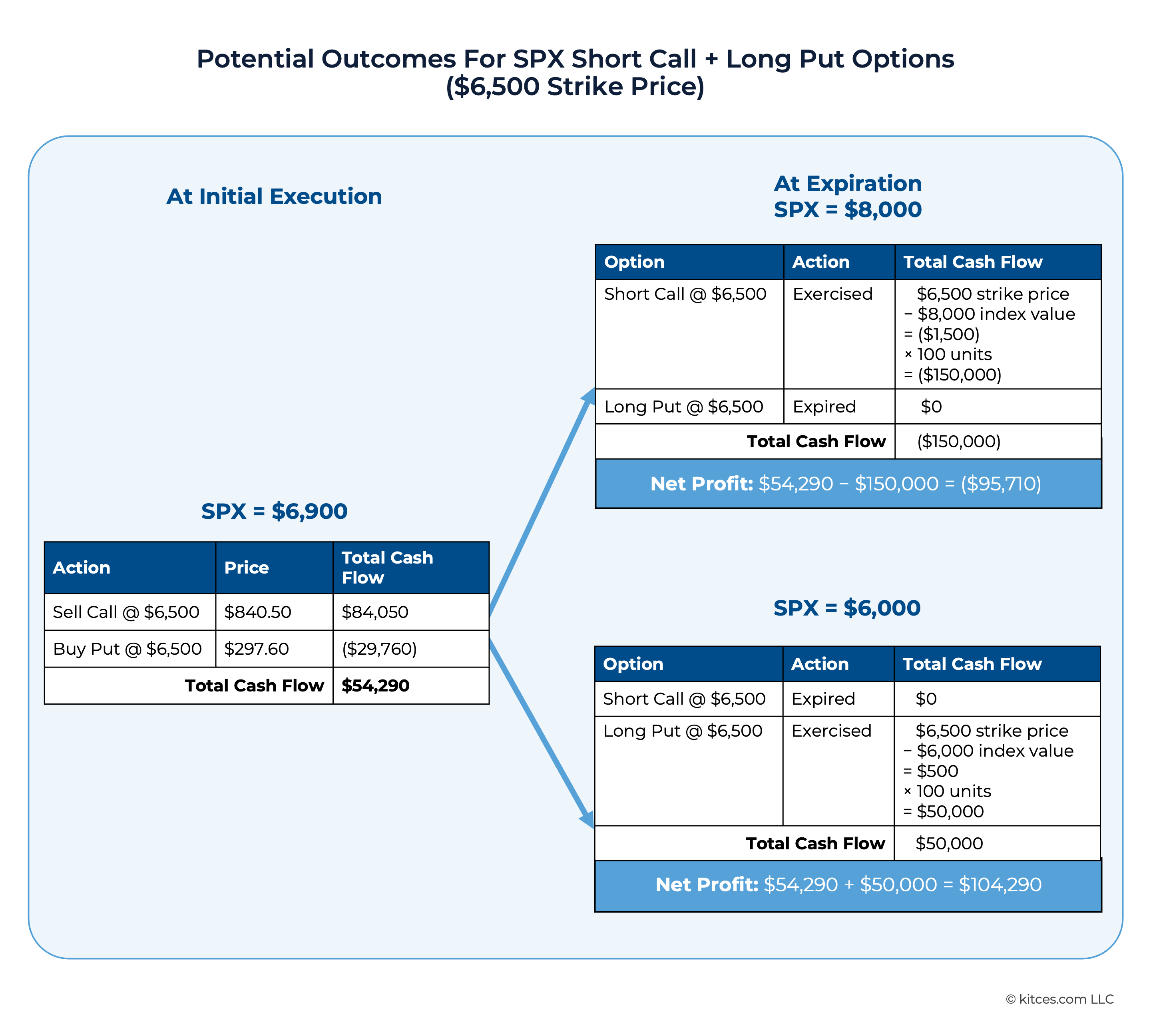

Example 3: Celia sells one call option and buys one put option on SPX, both with a strike price of $6,500 and an expiration date one year from today. She receives a premium of $840.50 per share for the call option, and pays a premium of $297.60 per share for the put option, meaning that she receives a net premium of 100 × ($840.50 − $297.60) = $54,290.

If SPX rises to $8,000 by the expiration date, Celia's call option will be exercised and she will be forced to sell the index units for $6,500, paying a total of $100 × ($8,000 − $6,500) = 150,000 (and incurring a net loss of $150,000 − $54,290 = $95,710 after accounting for the initial net premium that she received).

However, if SPX's price instead declines to $6,000, Celia can exercise her put option and sell the index units for $6,500, realizing a positive value of 100 × ($6,500 − $6,000) = $50,000 (and a net gain of $50,000 + $54,290 = $104,290 after accounting for the net premium received). In other words, no matter what the index does, Celia will sell 100 units for $6,500 – her profit or loss depends on whether SPX closes above or below that level.

Likewise, buying a call option and selling a put option at the same strike price and with the same expiration date guarantees that the investor will buy the underlying security at the strike price. Again, if the security's price rises above the two options' strike price, the call option will be exercised; if it falls below the strike price, then the put option will be exercised.

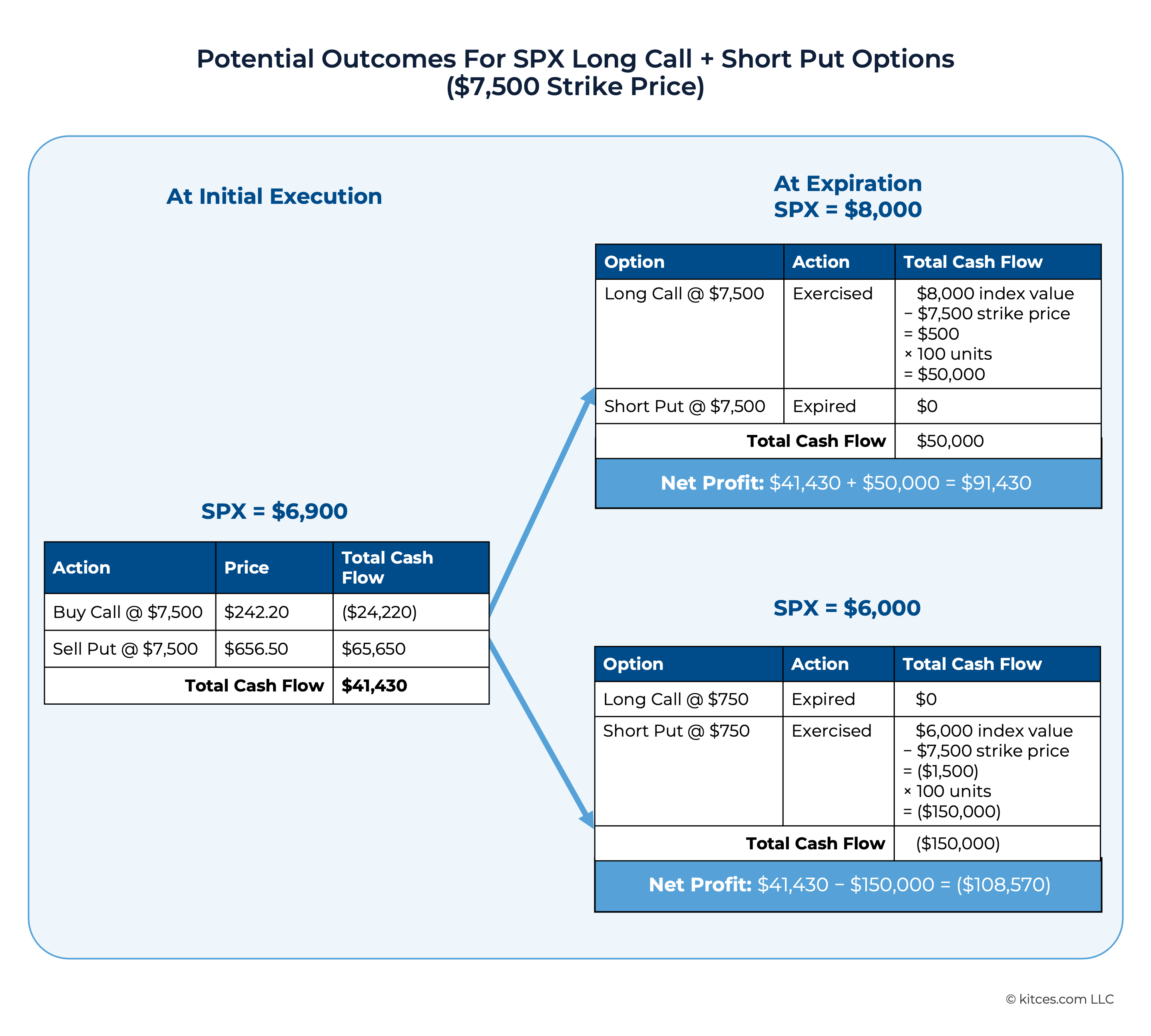

Example 4: Diana buys one call option and sells one put option on SPX, both with a strike price of $7,500 and an expiration date one year from today. She pays a premium of $242.20 per share for the call option, and receives a premium of $656.50 for the put option, meaning that she receives a net premium of 100 × ($656.50 − $242.20) = $41,430.

If SPX's price rises to $8,000 by the options' expiration date, Diana can exercise her call option and buy the index for $7,500, receiving 100 × ($8,000 − $7,500) = $50,000 (and realizing a net profit of $50,000 + $41,430 = $91,430 after accounting for the net premium received).

However, if SPX declines to $6,000 after one year, Diana's put option will be exercised, and she will be required to sell the index for $7,500, paying 100 × ($7,500 − $6,000) = $150,000 (and incurring a net loss of $150,000 − $41,430 = $108,570 after accounting for the premium received).

Again, the price at which Diana sells the index doesn't change in this strategy, regardless of SPX's direction.

On their own, these strategies are obviously very risky, with the potential for large profits or losses depending on which direction the underlying index goes. However, combining them together – i.e., selling a call option and buying a put at a lower strike price, and buying a call option and selling a put at a higher strike price, all with the same expiration date – guarantees the same outcome no matter where the price of the underlying security ends up. When the options expire, the investor will simultaneously buy the underlying security at the first strike price, and sell it at the second, paying the net amount of the difference between the two strike prices times the number of shares purchased. This combination of options is what it known as a box spread.

On their own, these strategies are obviously very risky, with the potential for large profits or losses depending on which direction the underlying index goes. However, combining them together – i.e., selling a call option and buying a put at a lower strike price, and buying a call option and selling a put at a higher strike price, all with the same expiration date – guarantees the same outcome no matter where the price of the underlying security ends up. When the options expire, the investor will simultaneously buy the underlying security at the first strike price, and sell it at the second, paying the net amount of the difference between the two strike prices times the number of shares purchased. This combination of options is what it known as a box spread.

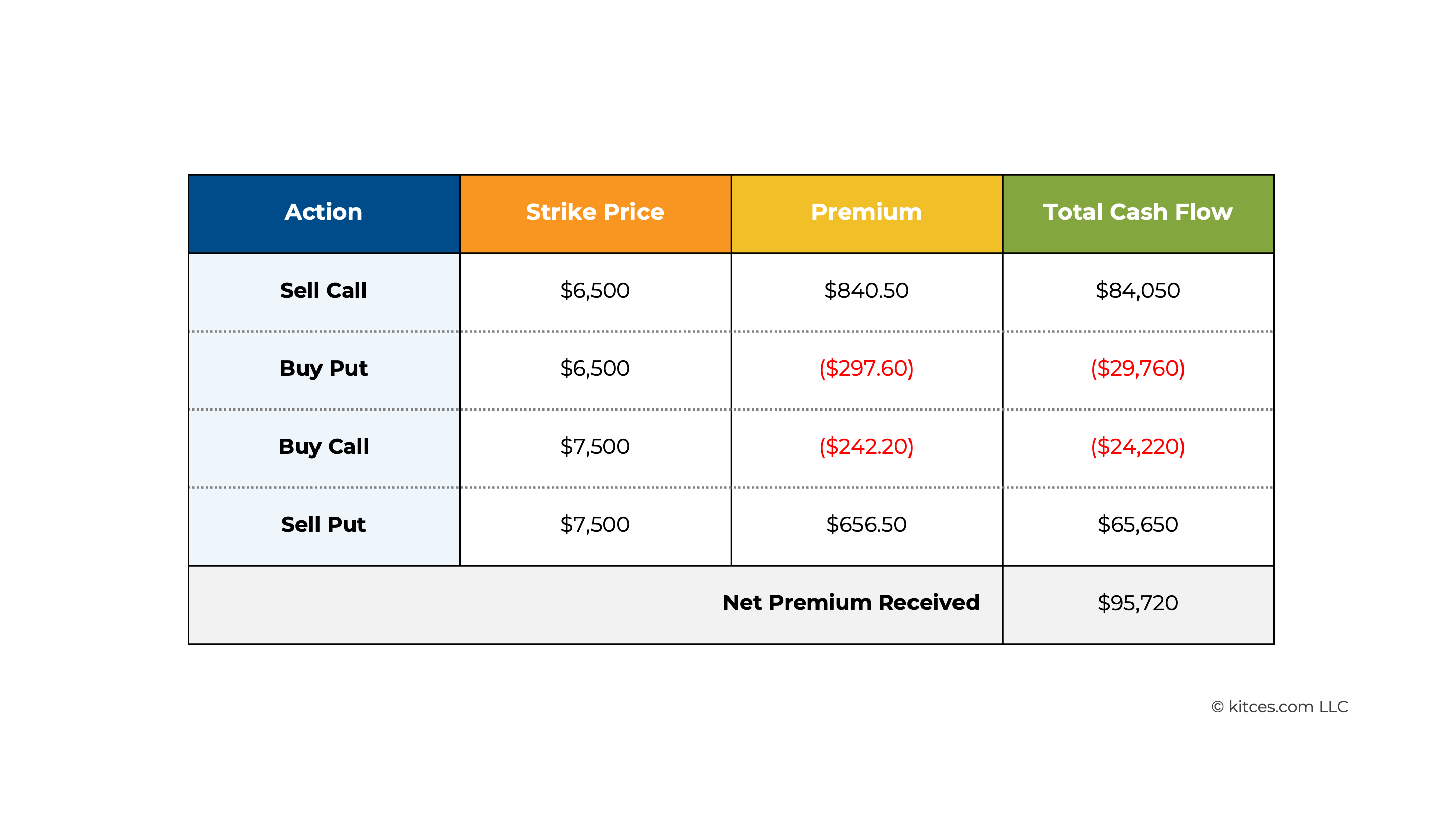

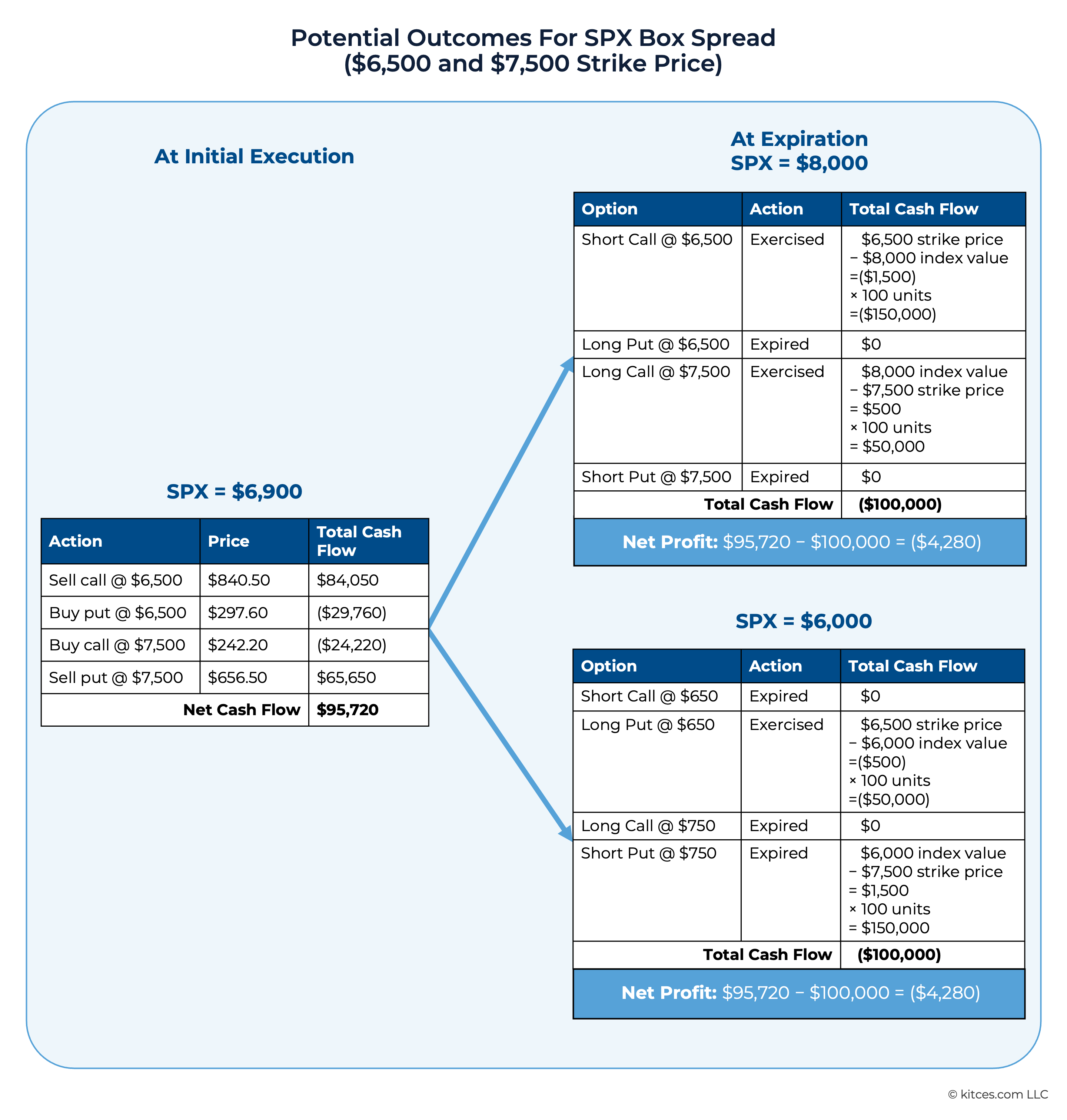

Example 5: Elena enters into four separate options contracts on SPX at once, all with the same expiration date one year from now:

As shown above, Elena receives a net premium of $95,720 upon initiating the options.

In one year, if SPX's price increases to $8,000, the two call options will exercise. The short-call option (i.e., the one Elena sold) will result in Elena paying 100 × ($8,000 − $6,500) = $150,000, while the long-call option (i.e., the one Elena bought) will pay 100 × ($8,000 − $7,500) = $50,000, with the two positions netting out to a total payment (i.e., negative cash flow) of $100,000. Because the two put options weren't exercised, they both expire with $0 value.

If SPX's price decreases to $6,000, however, the two put options will exercise. The long-put option will pay 100 × ($6,500 − $6,000) = $50,000 to Elena, and the short-put option will require her to pay 100 × ($7,500 − $6,000) = $150,000. Again, the two put positions net out to negative $100,000, and the call options expire with $0 value.

In other words, no matter where the price of SPX ends up, the box spread strategy will result in Elena receiving $95,920 in net premium payments today and paying $100,000 in one year when the options contracts expire.

As the example above shows, the mechanics of a box spread guarantee that the investor will receive a net premium payment at the initial execution of the strategy, and will pay a fixed amount back at the option contracts' expiration (with the amount paid always being more than the amount received due to the time value of money that's baked into the option's price). In the example above, the amount paid back in one year is ($100,000 − $95,720) ÷ $95,720 × 100 = 4.47% more than the initial premium. Which is another way of saying that the box spread is effectively a loan of $95,720, paid back in one year with 4.47% interest.

This is the basic concept of borrowing money via a box spread: the borrower receives an upfront net premium payment and repays a slightly higher amount – effectively the principal plus interest – when the options expire. Which makes the box spread similar to a zero-coupon bond, since, instead of making regular payments of interest or interest plus principal, as would be the case with most loans, with a box spread the borrower must repay the entire amount of principal and interest when the options expire. At that point, however, it's usually possible to roll the existing options into a new box spread, and to continue doing so each time they expire – indefinitely – as long as the borrower has enough funds in their account to cover the liability (which we'll discuss more below).

Why The 'Interest' On Box Spreads Is Lower Than Other Loans

Box spreads may seem like a complicated way to borrow funds, but they offer key advantages over other forms of borrowing.

Traditional lenders set their interest rates based on a market rate, such as the Prime Lending Rate or Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR), plus a spread that varies largely based on the lender's likelihood of getting paid back. E.g., collateralized loans like mortgages, auto loans, and securities-backed loans have lower interest rates than unsecured credit cards and personal loans, since if the borrower can't pay back what they owe, the lender can always seize the collateral and recover at least part of the outstanding liability. But even borrowers of collateralized loans still end up paying a higher interest rate than, for instance, Treasury bonds, because there's always some risk of default that the lender needs to be compensated for, and on top of that the lender has costs for overhead, regulatory requirements, and some amount of profit margin that it also needs to account for when it sets its rates.

By contrast, a box spread doesn't go through a specific lending institution, but through the options market. And the time value of money that's baked into options pricing is based on the 'risk-free' interest rate, which is very close to the rate on Treasury bills. And so, after stripping out the effects of market movements – which is what the options structure of the box spread does – one is left with a borrowing rate that is essentially the current Treasury bill rate, plus a small "convenience yield" after accounting for bid-ask spreads when buying and selling options in real time.

Hence it's possible to 'borrow' $95,720 via box spread at an effective interest rate of 4.47% (less than 1% higher than the current 1-year Treasury rate, which is 3.532% as of this writing), when borrowing the same amount as a margin loan would likely cost over 10%.

Taxation Of Box Spread Loans: Annual Deductions Against Capital Gains

The taxation of the 'interest' paid on a box spread loan is distinct from other types of borrowing. While the rules are complex, in general, losses from options contracts – and thus box spread loan interest – are usually treated as capital losses that are deductible against capital gains (or if there are no gains to deduct against, up to $3,000 per year of ordinary income, with the remainder being carried forward indefinitely). But the specific tax treatment depends on the type of options contract used to execute the box spread.

The vast majority of box spreads are executed using options on the S&P 500 index (SPX) (due to the deep liquidity of the SPX options market making it easier to match buyers and sellers and keep bid-ask spreads low). This makes them "nonequity options" under IRC Sec. 1256. Under the rules, Sec. 1256 contracts are marked to market each year, meaning that any unexpired contracts are treated as being sold for their fair market value on the last day of the year and netted together to produce an overall gain or loss. This gain or loss is treated as 60% long-term and 40% short-term.

For a box spread, then, there will generally be a deduction for part of the loan's total 'interest' in each year that the loan is outstanding, 60% of which will be treated as a long-term capital loss and 40% of which will be a short-term capital loss, even though the interest isn't actually paid until the box spread loan expires and is paid back in full.

Example 6: Felicity borrows $95,000 via a box spread using S&P 500 index (SPX) options during Year 1, for which she will need to repay $100,000 in Year 2. In other words, her 'interest' on the $95,000 loan equals $5,000.

At the end of Year 1, marking the option values to market results in a net capital loss of $2,000. Felicity will be able to deduct 60% × $2,000 = $1,200 as a long-term capital loss and 40% × $2,000 = $800 as a short-term capital loss.

In Year 2, when Felicity repays the box spread loan, she'll be able to deduct the remaining 'interest' of $3,000, of which 60% × $3,000 = $1,800 will be treated as a long-term capital loss and 40% × $3,000 = $1,200 will be treated as a short-term capital loss.

Nerd Note:

Sec. 1256 losses can also be carried back up to 3 years, meaning they can be deducted against a prior year's net Sec. 1256 income. However, they can only be carried back (1) to the extent that the current year's net Sec. 1256 loss exceeds $3,000, and (2) to the extent of net Sec. 1256 gains in any prior year. Since box spreads aren't likely to produce any Sec. 1256 gains (given that they're guaranteed an overall net "loss"), it isn't likely that many box spread borrowers will be able to carry back their losses, unless they do other forms of options trading that result in Sec. 1256 gains.

In the relatively rare cases of box spreads executed using options on actual securities like equities and ETFs, the capital gains and losses are not marked to market for tax purposes; instead they are recognized only when the box spread loan is paid back. Most of the time, these losses are treated as short-term capital losses, but there are instances (e.g., when the box spread lasts for more than one year) in which there are long-term capital losses as well.

But regardless, the tax treatment of box spreads as an option strategy rather than a standard loan means that the 'interest' paid is always tax-deductible. This is in contrast to standard loan interest, which is only deductible in certain cases, such as a qualified mortgage, student loan, auto loan, or investment loan interest. And in most cases, the Sec. 1256 treatment of box spreads means that the 'interest' can be partially deducted each year, while other forms of interest deductions are only allowed in the year the interest is actually paid.

The caveat, though, is that the deduction for 'interest' on box spread loans can only be taken against capital gains income. And while short-term capital gains income is generally taxed at the same rates as ordinary income (10%, 12%, 22%, 24%, 32%, 35%, and 37%), income from long-term capital gains is taxed at lower rates (0%, 15%, and 20%), which means that deductions from capital gains income will usually result in less tax savings than equivalent deductions from ordinary income.

All things being equal, then, it would be better from a tax perspective to take a traditional loan over a box spread loan if the traditional loan interest were deductible against ordinary income. However, as will be covered more below, the occasions when a box spread loan might be worth considering are usually when a tax-deductible traditional loan wouldn't be an option. When faced with taking a (capital gains income) deductible box spread loan or a (non-deductible) margin or SBLOC loan, it's better to take the one that's deductible against capital gains than the one that's not deductible at all (even setting aside the fact that the interest on the box spread loan would most likely be lower before even considering the tax deduction)!

Avoiding Margin Calls When Borrowing Via Box Spread

There's very little inherent risk in the box spread strategy itself. The outcome remains the same no matter what direction the underlying security or index moves, and option trades are guaranteed by the Options Clearing Corporation (OCC), meaning that if the parties taking the other sides of the options trades aren't able to fulfill their end of the transaction for any reason, the OCC will step in and complete the trade. The OCC is backed by collateral from its member organizations and was able to back 100% of derivative contracts in extreme market crashes like those in 2008 and 1987 (and is designated as a Systemically Important Financial Market Utility (SIFMU), giving it access to additional liquidity from the U.S. Federal Reserve in the event of an extreme market crisis). That isn't to say there's zero risk that a box spread loan could be threatened by a counterparty's inability to pay their side of the contract, but the risk is on an approximate level with the U.S. Treasury defaulting on its obligations – that is, extremely remote.

However, there is a market-related risk that box spread borrowers need to be aware of: margin calls from their broker-dealer if the value of their own portfolio assets drops too low.

A person who borrows funds via a box spread is subject to their custodial broker-dealer's margin maintenance requirements: the broker-dealer wants to ensure that someone with a short options position (which is essentially what a box spread is) has enough funds to close out their position if and when the options are exercised. Typically, this means that the maximum amount that can be borrowed via box spread is limited to a certain percentage of the borrower's taxable portfolio value. In typical (Reg T) margin accounts, the amount that can be borrowed and withdrawn from the account via box spread can't exceed 50% of the portfolio's value at the time of withdrawal, and can't exceed 70% of the portfolio value at any point without triggering a margin call. In this case, however, the 'borrowed' amount also includes the amount that must eventually be paid back as 'interest', meaning that the amount that can actually be withdrawn for the box spread is less than 50% of the portfolio's value.

Example 6: Geena has $1 million of investments in her taxable brokerage account. She executes a box spread for which she receives $500,000 in net premium, and will pay back $525,000 in one year. Her initial portfolio margin limit is 50% × $1 million = $500,000; however, that amount must be reduced by the 'interest' on the loan of $525,000 − $500,000 = $25,000. So, the actual amount that Geena can withdraw from her portfolio is only $500,000 − $25,000 = $475,000.

Because box spreads are subject to these margin requirements, a significant market drop could result in a margin call where the borrower needs to add collateral to their account or risk their investments being liquidated to cover their liability.

Example 7: Harriett has $1 million of investments in her taxable brokerage account. She executes a box spread for which she receives $380,000 in net premium, and will pay back $400,000 in one year. Because the total $400,000 liability is lower than her margin requirement of 50% × $1 million = $500,000, Harriett can withdraw the entire $380,000 that she has borrowed.

However, imagine that there is a severe market decline which causes the value of Harriett's investments to decline by 50%, to $500,000. Now, her $400,000 liability is 80% of her account value, which exceeds her maintenance margin limit of 70%. Harriett will need to add at least ($400,000 ÷ 70%) − $500,000 = $71,429 to her account to avoid it being liquidated.

Although a 50% portfolio decline leading to a margin call on a box spread loan would hopefully be a rare occurrence, it's at least within the realm of possibility. And if there were a margin call during a steep market decline, consider how it might require the borrower to liquidate other investments or borrow funds from other sources at the worst possible time, when asset prices are at their lowest and credit is hard to find.

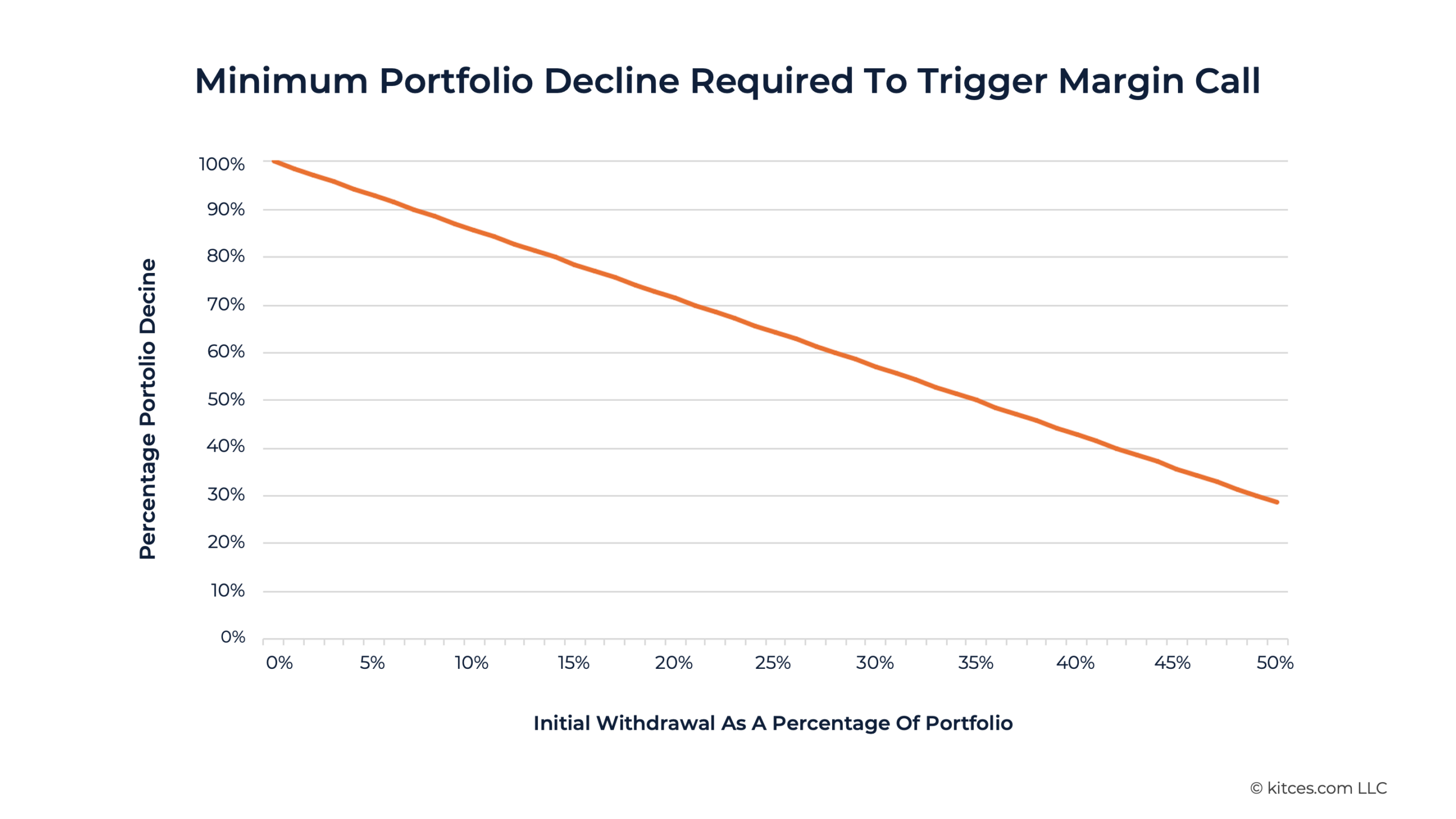

The simplest way to avoid a margin call on a box spread loan is to borrow a smaller percentage of the total portfolio value. If a person borrows the maximum initial 50% of their portfolio value, then the portfolio value would need to drop by 1 – (50% ÷ 70%) = 28.6% to trigger a margin call. If they borrowed 25% of their portfolio's value, the portfolio would need to drop by 1 – (25% ÷ 70%) = 64.3%. The lower the initial loan value as a percentage of a portfolio, the less likely that even a severe market decline will trigger a margin call.

Another option would be to consider applying for portfolio margin rather than traditional Reg T margin on the account where the box spread is executed. Rather than being based on static percentages of the portfolio's value, portfolio margin is a more dynamic calculation based on the portfolio's overall risk, and can therefore allow for lower margin percentages – i.e., to borrow a higher percentage of the portfolio's value. This can allow the portfolio to withstand a larger dip before incurring a margin call on a box spread loan – though ultimately, as with any loan, the borrower will need to pay it back when it's due, and they'll need to make sure they have the assets to do so once the box spread expires.

When To Use Box Spreads

Box spreads can be operationally difficult to execute and manage at scale, which is why even though the concept has been around for decades, they haven't been commonly used as a source of borrowing. However, new providers such as SyntheticFi and Vest Synthetic Borrow have arisen to handle the operational side of box spread lending. Which makes it easier for advisors who don't generally deal in options trading to help their clients employ box spread loans, and makes it potentially worth identifying client situations where a box spread loan could be appropriate.

At the beginning of this article, I described a hierarchy of different loan types based on the situations in which they're taken. There's no one type of loan that beats all others every time, and box spreads are no exception. A person buying a home might prefer the ordinary income deduction and extended, predictable payoff schedule of a traditional mortgage over the capital gains deduction and shorter term of a box spread. (Since options contracts rarely extend more than five years, box spreads can't extend any further than that either.) A student loan borrower might rather have the interest subsidy and potential for loan forgiveness offered by Federal student loans. Many of the 'Tier 1' loans in the hierarchy – reproduced below – would still be the best option for their particular use cases, even if a box spread loan were available.

Where box spread loans are more competitive, however, is in the 'Tier 2' area currently occupied mainly by HELOCs, margin loans, and SBLOCs. These have all been traditionally seen as sources of emergency or bridge funding – e.g., funds used to act on an investment opportunity, cover a large expense, or pay a tax bill without liquidating other assets. This is perhaps the best use case of box spread loans: As an alternative to these (usually non-deductible) loan types, for which box spreads can potentially offer both a lower interest rate and deductibility of interest against capital gains income (which is better than no deduction at all).

There are even cases when a box spread could compete against some of the 'Tier 1' loans above. For instance, interest on a HELOC used to pay for property renovations is generally tax-deductible against ordinary income. Hence, for someone in the top 37% tax bracket who borrows from a HELOC at a 7.5% interest rate, the effective interest rate after the deduction would be 7.5% × (1 – 37%) = 4.725%. However, if they borrowed in the form of a 1-year box spread, their interest rate would currently be around 4.0% before the deduction for capital gains – if the borrower is in the top 23.8% capital gains rate, their effective interest rate on the box spread would be 4.0% × (1 – 23.8%) = 3.048%. In this case, the box spread is a better loan than the HELOC, even though the HELOC receives a deduction against ordinary income and the box spread can 'only' be deducted against capital gains.

The key point is that while box spreads won't necessarily supplant mortgages, Federal student loans, and other types of 'Tier 1' loans in the lending hierarchy, they could still fulfill an important role for clients who are in need of debt solutions and who have the portfolio assets to borrow against. Whereas many advisors have traditionally recommended HELOCs and SBLOCs as sources of credit in these cases, the interest rates available on box spreads, and the relative speed and ease with which a box spread can now be set up through a third-party provider, could make them a better option to meet the client's needs.