Executive Summary

Financial advisors have a fiduciary duty to their clients, meaning that they must take the client's interests into account when making recommendations and acting on their behalf. Usually, fulfilling that duty involves listening to the client to understand their wishes and acting accordingly to ensure those wishes are carried out. However, the situation becomes more complicated if the advisor suspects that the client may have a diminished capacity to make sound financial decisions on their own.

When clients exhibit signs of cognitive decline, advisors must navigate a tricky tightrope of conflicting goals and obligations. On the one hand, an advisor's desire to respect and uphold the client's wishes (and their desire not to lose the client) may lead them to follow the client's instructions at all times, even when the advisor might find them suspicious (e.g., if the client requests a large withdrawal to invest in the business of a 'friend' they've never mentioned before). But on the other hand, the advisor's duties of care and loyalty, as well as a growing number of elder-abuse prevention laws enacted in many states, compel the advisor to intervene to prevent actions that could cause harm to the client and/or to notify authorities when they suspect the client is being exploited.

As life expectancies increase and the population ages, cognitive decline is unfortunately on the rise. It's therefore a best practice for financial advisors – particularly those who serve retirees and elderly clients – to establish processes that enable them to recognize potential cognitive decline or exploitation when it occurs, and to handle those situations in a manner that meets their ethical and regulatory obligations. Having these processes in place before diminished capacity arises can ease the challenge of navigating situations where the advisor's fiduciary duty may come in conflict with the client's express wishes.

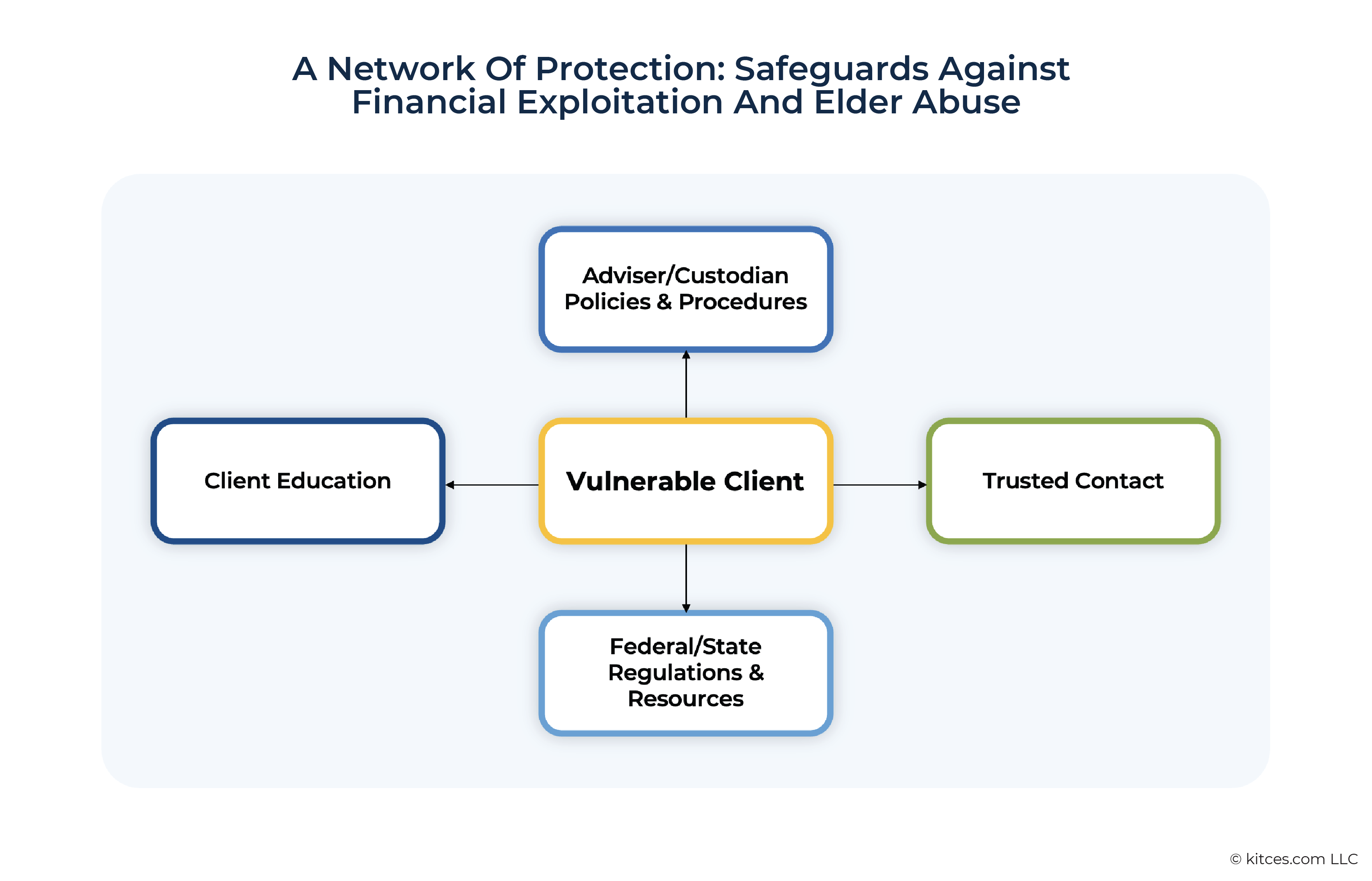

The process can start with training and education, for both advisors and clients, on the signs of cognitive decline and/or financial exploitation. Ensuring that the client is aware of the risk of fraud and abuse as they age can help reassure the client that the advisor is proactively involved in protecting their interests and create awareness that the advisor will act if they suspect abuse is occurring. Advisors can also ask their clients to name a 'trusted contact' who can be involved if the advisor observes concerning behavior or is unable to reach the client (and having the contact authorized by the client in advance can help the advisor avoid breaching any privacy laws if they later feel the need to engage a third party in the conversation).

When an advisor notices signs of cognitive decline or abuse, they aren't expected to make a medical diagnosis. Instead, they can note (and document) instances where the client's behavior or desires are inconsistent with their past behavior and emphasize their desire to protect the client's interests. State laws often grant advisors the authority to delay requested disbursements of funds in cases of suspected fraud, providing the advisor with additional time to investigate and discuss the situation with the client. And even though the client may push back, keeping the emphasis on the actions rather than the client's behavior – e.g., noting that the client's actions appear unusual based on their past behavior and that firm policy requires further review in such cases to protect client assets – affirms that the advisor's primary concern is on acting in the client's best interest, rather than confronting the client about their cognitive ability.

Ultimately, while it's challenging to face clients experiencing cognitive decline – especially in deep and long-lasting client relationships – advisors have a critical role to play in ensuring that decline doesn't lead to abuse, fraud, and/or loss of the client's savings. By proactively putting procedures in place to prepare for, detect, and handle such situations as they arise, advisors can fulfill their legal and ethical duties – but more importantly, safeguard their clients' assets when the client is no longer able to do so themselves.

As America's population ages, advisors increasingly encounter clients with a declining ability to make sound financial decisions – which leaves them vulnerable to financial losses either due to their own inability to make sound decisions or because of the exploitative influence of others. Improper handling of such situations can lead not only to regulatory risk, but also to the potential termination of the client relationship due to improper handling – or worse, a complaint or legal action. Yet, there are numerous complexities that make management of such situations challenging.

For starters, no single law prescribes exactly what an advisor must do to handle situations involving diminished capacity and financial exploitation. Advisors operate under a web of SEC regulations, privacy restrictions, and inconsistent state reporting statutes, which can make it confusing to address such situations. Additionally, because situations involving cognitive decline often occur gradually and unpredictably, it can be challenging for advisors to determine if and when a client is facing diminished capacity or financial exploitation.

These factors, coupled with a desire not to offend clients and risk losing the client relationship, can present landmines that advisors must navigate carefully. Addressing these situations successfully requires knowledge of the advisor's legal obligations, a well-conceived plan to mitigate risks and manage interventions effectively, and clear communication with clients.

Regulatory Responsibilities For Advisors When Addressing Diminished Capacity And Financial Exploitation

No single law dictates how advisors must respond when a client begins showing signs of diminished capacity and/or financial exploitation. Federal fiduciary duties require advisors to act in the client's best interest. State laws may mandate reporting of suspected exploitation. Meanwhile, privacy rules limit how much information can be shared, even with family members. Understanding how these laws interact is the first step toward designing an effective response.

The Investment Advisers Act Of 1940

For SEC‑registered advisers, the cornerstone of regulation is the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. Although the Advisers Act never explicitly mentions "diminished capacity" or "financial exploitation," its fiduciary principles implicitly fill that gap. Sections 206(1) and 206(2) prohibit fraud and deceit and require advisors to act under a duty of care and loyalty toward clients, requiring them to act in the best interest of clients. In practice, this means advisors must take reasonable steps to protect clients from foreseeable harm, including the risk that cognitive decline could impair financial decision‑making.

To satisfy their fiduciary obligations, advisors must show more than good intentions. They must also demonstrate that they took reasonable and documented steps to protect a client's interests. In situations involving diminished capacity, this means observing, recording, and escalating concerns through an established process. The advisor's role is not to diagnose medical conditions but to recognize when a client's financial behavior suggests risk and to be prepared to respond in such circumstances.

For example, if a long‑time client suddenly begins liquidating accounts to invest in a questionable business promoted by a new 'friend', the advisor has a duty to pause and assess whether that transaction aligns with the client's objectives and risk tolerance. Doing nothing might expose the firm to claims of negligence or a breach of fiduciary duty. Acting too aggressively, however, could lead to claims that the RIA breached its fiduciary duty by going against the client's expressed wishes. While there may be no clear answer as to how to address each situation, a sound process for handling such situations can serve as a powerful defense against claims of a breach of fiduciary duty owed to the client.

Having and following such a process is not only a best practice but also a requirement under the Advisers Act Rule 206(4)‑7, which requires every RIA to adopt and enforce written policies and procedures reasonably designed to prevent violations of the Advisers Act. Regulators interpret that rule broadly. If an advisor regularly serves senior clients but lacks policies addressing diminished capacity or financial exploitation, the SEC may view this as a compliance failure. Examiners often request copies of a firm's internal policies, employee training materials, and records of past incidents related to exploitation. An advisor that fails to produce such documents could be seen as violating Rule 206(4)-7 and thus be exposed to claims of a breach of fiduciary duty.

State Elder Protection Laws

Even though SEC‑registered advisors operate under Federal law, state elder‑protection statutes still apply. Many advisors mistakenly believe that Federal regulations preempt state law, but they do not in this case. Instead, state laws often add another layer of responsibility, particularly regarding reporting requirements for suspected exploitation.

Nearly every state has enacted some form of legislation to protect vulnerable adults from financial exploitation, most of which are modeled on the North American Securities Administrators Association's Model Act to Protect Vulnerable Adults from Financial Exploitation (NASAA Model Act). The NASAA Model Act serves as a framework for states to follow in crafting their own laws. It was designed to give investment advisors both the authority and the obligation to take preventive action when they suspect financial exploitation.

Under the Model Act, two core principles guide state laws:

- Mandatory or permissive notification: Advisors and other "qualified individuals" must, or in some states may, report suspected exploitation of an older or vulnerable adult to the state securities regulator and/or Adult Protective Services. The purpose is to ensure that authorities can intervene quickly to protect the client's assets.

- Authority to delay disbursements: The Model Act empowers firms to place a temporary hold on disbursements of funds or securities from a client's account when financial exploitation is suspected. This hold is meant to prevent immediate harm while an investigation is conducted, generally for a limited duration, such as 10 to 15 business days, with possible extensions if regulators request additional time.

While these two concepts form the backbone of most state laws, the details of implementation vary widely. States differ in whether reporting is mandatory or discretionary, which agencies must be notified, the permissible hold length, and whether the laws apply to all financial professionals or only to certain categories of financial institutions.

These variations underscore the fact that the NASAA Model Act is not a uniform law, but rather a blueprint policy. Each state that has adopted it has tailored its provisions to reflect local priorities, regulatory structures, and legal definitions of "vulnerable adult".

For firms with clients across multiple states, this inconsistency creates operational challenges. Advisors must determine which rules apply based on where the client resides, not where the firm is located. A client living in Florida triggers different obligations than one residing in New York. As such, it's vital for advisors to understand the state laws that apply specifically to their clients. While there are databases that provide a survey of applicable state laws, it's critical to independently confirm that these databases are up to date, given that state laws can change over time.

Privacy Regulations

The intersection of elder client protection and privacy law is one of the trickiest areas advisors face. On one hand, advisors have a fiduciary duty to act in the client's best interest and prevent harm, which they may believe is assisted by contacting family members or other loved ones to check in on the client. On the other hand, Regulation S‑P prohibits disclosing nonpublic personal information about clients to third parties without their consent. This creates what some compliance professionals call the 'good intentions trap'. An advisor who shares information to prevent exploitation may still be in violation of Federal privacy regulations.

In the context of diminished capacity or suspected financial exploitation, nonpublic information would include not only information about the client's financial circumstances and accounts, but also details about health concerns and warning signs of diminished capacity or financial exploitation.

Given the numerous laws in play when handling these issues, it's imperative that advisors adopt robust measures to mitigate such risks.

How Advisors Can Take Measures To Mitigate Risk When Handling Situations Involving Diminished Capacity Or Financial Exploitation

The most effective strategy for handling diminished capacity is prevention. Advisors should anticipate these situations long before they happen by building systems that identify and address risk early. Three core pillars of an effective risk prevention scheme include client education (including encouragement for the client to designate a trusted contact), employee training, and robust procedures for intervention.

Client Education And Trusted Contacts

Educating clients about the risks of financial exploitation and the warning signs of diminished capacity is the most effective yet frequently neglected form of prevention. Advisors are uniquely positioned to initiate these conversations because clients often trust them more than any other financial professional with whom they are working.

advisors should weave education into the client relationship from the outset, rather than just after concerns arise. New client onboarding packets can include materials from the SEC's Office of Investor Education, FINRA's Senior Helpline, or the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. These resources explain common scams, such as impostor schemes, fraudulent investment pitches, and romance scams targeting older adults. Providing credible, easy-to-read educational materials can reassure clients that the advisor is proactive about protecting their interests.

Ideally, education should also extend to family members or other trusted contacts. Facilitating family meetings early in the client relationship can help establish clear communication lines and expectations before any signs of diminished capacity appear. These discussions should define who is authorized to make financial decisions and under what circumstances, and how the advisor will handle communications if concerns arise. By involving families in advance, advisors reduce confusion and mitigate potential conflict later.

Practical steps advisors can take to integrate client education include:

- Including elder-fraud awareness information in client newsletters or digital portals.

- Hosting annual educational webinars or seminars focused on protecting against scams.

- Encouraging clients to complete 'trusted contact' forms during account setup.

One of the most effective preventive strategies is to encourage clients to designate a trusted contact with whom the advisor can communicate in the event the firm is concerned about the client's wellbeing. Although not explicitly required, the practice derives from FINRA Rule 4512, which mandates that broker-dealers obtain a trusted contact for each retail client. The SEC and state regulators now view this as the best practice for all advisors.

It is essential to note that a trusted contact is not the same as a power of attorney or co-signer. They cannot make direct transactions or access account assets. Their purpose is limited: they serve as an alternative communication channel if the advisor observes concerning behavior or is unable to reach the client. The advisor may want to inform the trusted contact and gather more information regarding how to respond without violating applicable privacy rules, such as Regulation S-P. This limited scope is critical for maintaining client autonomy while providing a layer of protection. By obtaining advance authorization in writing, advisors can avoid the later dilemma of choosing between protecting a client and violating privacy regulations.

advisors who present the trusted contact process as a standard element of firm policy rather than as a signal of concern about the individual client reduce the stigma associated with cognitive decline and normalize the practice for all clients, regardless of age. That normalization makes it far easier to activate the provision later without surprising or offending the client.

Employee Training

Employee training can go a long way toward mitigating risk when a client is facing suspected diminished capacity or financial exploitation. Training should include education on identifying warning signs, as well as reinforcement of proper protocols for communicating with firm supervisors and clients when there is suspected diminished capacity or financial exploitation.

As noted earlier, it can be difficult to identify when a client is facing cognitive decline as the onset of symptoms may be gradual or unpredictable. Employees are not medical experts, and therefore are not required to make medical diagnoses. However, they are obligated to identify when a client's cognitive state is likely to impact their financial affairs.

Warning signs of diminished capacity may include, among others:

- The client repeatedly forgets prior conversations or provides conflicting instructions.

- Uncharacteristic changes in spending or investment behavior.

- Difficulty understanding previously familiar concepts or documents.

- Signs of confusion about account values, fees, or statements.

- Reliance on new, unfamiliar individuals for decision-making.

Expressions of anxiety or distress related to finances.Warning signs of financial exploitation may include, among other things:

- Sudden large withdrawals inconsistent with prior behavior.

- New names added to accounts or beneficiary designations.

- Third parties speaking on behalf of the client or appearing to control communications.

- Pressure from relatives, caretakers, or 'friends' to transfer funds or make gifts.

- Unexplained changes in legal documents, such as powers of attorney.

- Complaints of missing funds or unauthorized activity.

Additionally, employees should receive ongoing training on the latest scams so they can be prepared to respond expeditiously if those situations surface.

In addition, employee training should not focus exclusively on detection, but also on responding appropriately when situations arise. Among other things, employees must be trained on when and how to document situations involving diminished capacity and financial exploitation, including details of any identified red flags. Employees must also be trained on effective reporting protocols, including clear guidelines as to who they should report to and when such reports should be filed. Senior management should be given clear direction on when it's appropriate to bring in outside professionals, such as attorneys, if necessary, to handle high-risk situations.

Maintaining effective documentation and reporting protocols enables a firm to track situations as they evolve, thereby mitigating the risk that the firm will be caught off guard if the client's circumstances worsen. Effective training should also involve role-playing exercises to give employees a real-world feel as to how such situations may arise, so they are better prepared to handle such situations competently.

Policies And Procedures

While client and employee training are both critical, they are less effective without appropriate policies and procedures in place to ensure consistency in their application. Furthermore, policies and procedures help provide employees with more clarity when intervening in cases of diminished capacity and/or financial exploitation.

Ideally, policies and procedures should touch on the following:

- How the designation of a trusted contact should be handled and documented during the client onboarding process.

- When and how frequently clients will receive education on diminished capacity or financial exploitation.

- When and how often employees will be trained on identifying, responding to, and documenting situations involving diminished capacity or financial exploitation.

- When firm employees are authorized to reach out to trusted contacts.

- When the firm must report situations involving financial exploitation to the appropriate state authorities.

- When the firm will implement holdbacks on client-requested disbursements.

- How often the policies and procedures will be reviewed and updated.

How Advisors Can Intervene Effectively When Faced With Client Diminished Capacity Or Exploitation

When signs of diminished capacity or financial exploitation surface, financial advisors face one of the profession's most delicate challenges. How an advisor responds in these moments can have lasting consequences for both the client and the firm. The key is to act carefully to protect the client's assets while respecting their autonomy and dignity. Striking this balance requires structure, empathy, and a deep understanding of an advisor's legal obligations.

Intervention is not the time for improvisation. Advisors must rely on clear, written procedures that guide them step-by-step through what to do, who to contact, and how to document every action. A well-prepared firm will have policies that align with Federal and state law and that give employees the confidence to act when something doesn't feel right. A protocol that focuses on observation, documentation, and escalation can provide consistency and appropriate responses as situations arise and develop. Intervention is as much about preparation as it is about action.

Notification Protocols

When financial exploitation or diminished capacity is suspected, advisors often wonder: "What exactly should I report, and to whom?" The answer depends on both Federal and state rules. On the Federal level, the Senior Safe Act provides an important layer of protection. This law provides immunity from liability to firms and their employees who, in good faith, report suspected financial exploitation, so long as they've received appropriate training and the firm documents its actions carefully.

State laws add another dimension. Some states make reporting mandatory when an advisor suspects exploitation, while others allow (but don't require) such reports. The agencies involved can differ, too. In many states, advisors are required to report suspected financial exploitation to Adult Protective Services or the state securities regulator. The timeline for reporting and the threshold for suspicion also vary widely. What qualifies as 'reasonable belief' in one jurisdiction might not meet the same standard elsewhere.

To keep things organized, advisors should maintain a living document – a simple chart or jurisdictional matrix – that lists reporting duties for each state where the firm does business. This document should spell out whether reporting is required or optional, which agencies must be contacted, how quickly the report must be made, and whether the state allows or requires transaction holds. Having this information readily available can save valuable time during a crisis. The compliance team should periodically review and update the information, as state laws change over time.

Just as important as knowing where to report is keeping meticulous records. Advisors should note – ideally in their CRM or a log – who was involved, when discussions took place, what was said, and what decisions were made. Even a short note like "Client requested unusual withdrawal; compliance notified at 3:45 PM" can make a difference. These records protect both the firm and the advisor by demonstrating to regulators that the response was prompt, reasonable, and in good faith.

Disbursement Holdback Procedures

When potential exploitation involves suspicious transfers or withdrawals, advisors must act quickly. As discussed above, many states and custodians now allow firms to delay or temporarily hold disbursements when they suspect that a client is being exploited. These holds are not intended to restrict access – they are designed to prevent immediate harm while allowing time for investigation.

The best way to handle such situations is through a controlled process. Each firm should establish clear disbursement procedures that outline who can make the decision, how the client will be notified, and what comes next. In most firms, the authority to initiate a hold should rest with the Chief Compliance Officer or another senior employee. The procedure should also specify how long a hold can last and what documentation must accompany each step.

When a hold is placed, the client should be notified in a respectful and factual way. Advisors should avoid sounding accusatory. Instead, the communication can reference firm policy, such as: "Under our client-protection policies, we've temporarily delayed this transaction while we verify the details". Maintaining a neutral and professional tone helps maintain trust, even in tense situations.

Coordination with custodians is also critical. Many large custodians (e.g., Schwab, Fidelity, and Pershing) have their own protocols for handling suspected exploitation. Advisors should make sure their internal procedures align with these custodian requirements. This prevents duplication of efforts and ensures consistency.

Another important part of this process is disclosure. Advisors should consider including in their advisory contracts or Form ADV brochures a statement explaining that the firm may temporarily delay disbursements if financial exploitation or diminished capacity is suspected. Setting this expectation early makes intervention smoother and reinforces the advisor's role as a fiduciary safeguard.

Managing Client Resistance With Empathy And Documentation

One of the hardest parts of intervention occurs when the client disagrees with the advisor's actions. Clients who are facing cognitive decline often resist help or deny that anything is wrong. They may interpret an advisor's concern as intrusive or disrespectful. The challenge is in protecting the client's interests without undermining their sense of control.

Empathy and language choice can make all the difference. To avoid causing conflict, advisors can describe what they see, rather than what they think. For example, instead of saying, "I'm concerned you might be losing track of things," the advisor might say, "I've noticed a few transactions that don't match your usual pattern. Let's review them together". Sticking to objective facts can help reduce defensiveness and helps clients stay engaged in the conversation.

If a client continues to resist, advisors should refrain from arguing or attempting to diagnose the situation. Instead, they should follow the firm's escalation protocol. That usually means documenting the concern and referring the case to compliance or management for review. From there, the firm can decide whether to contact the client's trusted person, delay a transaction, or report the case to the proper authorities.

It's equally important to capture everything in writing. As mentioned earlier, advisors should keep detailed notes about all communications – what was said, how the client reacted, and what next steps were taken. These notes not only protect the advisor but also help regulators see that the firm acted with care and transparency.

Maintaining empathy doesn't mean avoiding tough decisions. Advisors can protect clients while still showing compassion by explaining the process in a supportive manner: "We have policies that require us to review certain activity when it looks unusual. Our goal is to make sure everything we do aligns with your long-term interests". This type of messaging reframes intervention as a partnership, not a confrontation.

Integrating Legal Awareness With Fiduciary Obligations

Ultimately, effective intervention requires advisors to see compliance and care as two sides of the same coin. Acting in a client's best interest sometimes means stepping in when the client cannot protect themselves. However, it also means respecting privacy, following the law, and ensuring that decisions are supported by documentation.

Firms should build these expectations directly into their compliance manuals. Policies should describe how the Senior Safe Act works, when reporting is mandatory under state law, and how to coordinate with custodians. Employees should know exactly whom to contact and what language to use when discussing potential exploitation. Templates for reporting, escalation memos, and client communications can reduce confusion and ensure consistency across the firm.

Good systems can transform stressful moments into manageable processes. When everyone knows their role, intervention becomes less about panic and more about professionalism. It becomes an extension of the firm's fiduciary duty rather than a disruption of it.

Effectively Managing Client Relationships After An Initial Intervention

The duty to respond to situations of diminished capacity or financial exploitation doesn't end once the immediate issue has been addressed. Effective management of the situation continues through structured follow-up, multidisciplinary coordination, and continuous oversight. When a firm handles these cases as part of its ongoing risk management and client service, it transforms what could have been a one-time crisis into a durable system of protection.

advisors must recognize that post-intervention work is not just administrative cleanup. It's an essential part of an advisor's fiduciary obligations, ensuring that the advisor's actions are consistent, defensible, and compassionate. Once a potential issue has been identified and addressed, the focus shifts to how the firm records its actions, communicates with stakeholders, evaluates the outcome, and monitors future risks. This requires input from multiple teams, including compliance, operations, client service, and, in some cases, legal counsel.

An effective way to ensure consistency in how post-intervention cases are handled is to establish an internal Elder Client Review Committee. This committee serves as a cross-functional team responsible for evaluating incidents, making decisions about disbursement holds or reports, and reviewing whether firm policies were followed. It creates a structure that moves decision-making away from a single advisor and toward a collective process informed by multiple perspectives.

The committee should include representatives from client service, operations, and compliance or legal departments. Each member brings a different lens: client service professionals can offer insights into behavioral changes or family dynamics, operations can assess account activity and disbursement risks, and compliance ensures all actions align with regulatory expectations. This collaboration not only improves decision quality but also demonstrates to regulators that the firm takes a systematic approach to handling such situations.

Cases reviewed by the committee should be logged in a centralized incident file. This log should capture key facts, including who identified the issue, what red flags were observed, the steps taken, and how the case was resolved. Having this information organized in one place creates a defensible record for regulators and auditors. It also helps the firm identify patterns, including whether certain types of accounts, relationships, or transactions appear repeatedly in elder-client cases – which can inform how the firm handles similar situations in the future.

Once the immediate response has been completed, the firm should focus on embedding the lessons learned into its ongoing compliance infrastructure. Policies addressing diminished capacity and financial exploitation should be written into the firm's compliance manual and operational procedures. Codifying these protocols ensures consistency and provides clear reference points for employees who may face similar situations in the future.

Annual training reinforces these policies and keeps employees aware of both the human and legal dimensions of working with clients who are experiencing diminished capacity. This training should do more than just review definitions or legal requirements. It should incorporate real-world scenarios and interactive discussions that help employees practice responding appropriately to sensitive situations.

To preserve eligibility for immunity under the Senior Safe Act, firms must also maintain proper training records. These records should document who received the training, when it occurred, and what topics were covered. Retaining this information not only satisfies legal requirements but also demonstrates the firm's ongoing commitment to protecting vulnerable clients.

Post-intervention protocols should not end with documentation and training alone. Maintaining ongoing engagement with the client and their trusted contacts is equally important. Once impairment has been confirmed, the advisor's role shifts from detection to long-term support. This stage is about ensuring continuity, respect, and stability in the client relationship while safeguarding their assets.

Communication is central to this process. Advisors should schedule regular check-ins with the client and any authorized trusted contacts or family members involved in the client's financial affairs. These conversations provide an opportunity to review account activity, confirm that safeguards are working, and identify any new behavioral or cognitive changes. The tone should be respectful and client-centered – focused on partnership rather than surveillance.

When necessary, advisors should help clients formalize financial management transitions. This might involve adding a co-trustee or successor fiduciary, working with an attorney to update powers of attorney, or coordinating with a family member or institutional trustee to ensure continuity. The advisor's role is not to replace the client's decision-making authority but to facilitate a smooth and transparent handoff that aligns with the client's long-term financial plan.

Periodic reviews of vulnerable clients should be part of the firm's standard compliance testing program. During these reviews, advisors can assess whether prior concerns have resurfaced, whether communication with trusted contacts remains current, and whether new red flags have emerged. Integrating these reviews into routine compliance testing embeds vigilance into daily operations and reinforces the firm's culture of care.

The benefits of this continuous approach go beyond risk mitigation. It strengthens client trust. Clients and families who see that the advisor is proactive and organized are more likely to stay engaged, even when facing difficult transitions. It also provides a tangible record that the firm's fiduciary responsibility extends to the client's wellbeing, not just portfolio performance.

Case Study On Handling Diminished Capacity And Financial Exploitation

To illustrate how the principles of prevention, intervention, and post-intervention coordination work in practice, consider the experience of Evergreen Advisory Partners, a (fictional) mid-sized registered investment advisor based in Colorado. The firm has a long-standing client base of retirees, business owners, and professionals, many of whom have been with the firm for decades. Evergreen's approach to client protection offers a model of how a firm can combine empathy, structure, and compliance rigor to navigate the complexities of diminished capacity and financial exploitation.

The Client And The Early Warning Signs

One of Evergreen's longest-tenured clients, Mary Thompson, was an 82-year-old retired teacher who had worked with her advisor, David Ross, for nearly twenty years. Mary was financially comfortable, independent, and proud of managing her affairs without family involvement. Over time, David noticed small changes during their quarterly reviews. Mary began to repeat questions, seemed uncertain about the purpose of her portfolio, and occasionally misplaced account statements. Initially, these changes seemed benign, but due to his training, David suspected that diminished capacity might be at play.

Evergreen's policies required all advisors to complete a brief 'client behavioral observation log' after each review with a client over the age of 70. These logs prompted advisors to record whether the client displayed signs of confusion, memory lapses, or changes in demeanor. David documented his observations objectively, noting that Mary appeared more distracted and occasionally forgot prior discussions. His entries didn't diagnose or speculate. Rather, they simply recorded observable facts.

Two months later, Mary called to request a $100,000 wire transfer to an account in Florida. When asked about the purpose, she said she was investing in a 'special opportunity' recommended by a new friend she had met online. David's training immediately kicked in. Evergreen's compliance manual required staff to flag any large, unusual withdrawals to the compliance officer if they appeared inconsistent with a client's past behavior. Rather than approving the request, David used the firm's 'Observe, Document, and Escalate' protocol to alert Evergreen's compliance team.

The firm's compliance team reviewed Mary's history and noted that this was the first wire request of that size in more than five years. They also reviewed the publicly available fraud alerts, which showed similar cases involving romance scams. The Chief Compliance Officer convened an emergency meeting of the firm's Elder Client Review Committee, a standing group composed of compliance, operations, and client service personnel.

Intervention And The Decision To Hold

The committee decided to place a temporary hold on the disbursement while the situation was reviewed. Evergreen's Form ADV already disclosed that it reserved the right to delay disbursements in cases of suspected exploitation, and its client agreements reinforced this authority. This early disclosure reduced the likelihood of confrontation later.

David contacted Mary to explain the delay in neutral, policy-based language. He said, "Under our firm's client-protection policy, we've temporarily delayed this transaction while we verify a few details. Our goal is to make sure this aligns with your long-term objectives". Although Mary was initially frustrated, the respectful tone and reference to firm policy helped defuse tension.

At the same time, the compliance officer reviewed applicable laws. Colorado permitted temporary disbursement holds and encouraged reporting suspected exploitation to Adult Protective Services and the state securities division. Acting in accordance with both state law and the Senior Safe Act, the firm filed a formal report, documenting each step with timestamps, notes, and email confirmations. Every conversation, from Mary's initial request to the compliance team's decision, was recorded in Evergreen's CRM.

The firm also contacted the custodian. Working together, the advisor and custodian were able to confirm that the supposed 'investment' was part of an organized online fraud scheme targeting older investors. Because of the temporary hold, the funds were never released.

Managing Resistance And Preserving The Relationship

After learning that the transaction had been delayed, Mary called David several times, insisting that she wanted to proceed. David relied on his training in empathetic communication. He avoided accusatory statements or personal judgments, instead focusing on observable facts. "Mary," he said, "we noticed that this transaction is unusual for your account and that similar requests have been linked to scams. Before we move forward, let's take a step back and verify everything together". His approach balanced concern and empathy.

The next step was to engage Mary's trusted contact, whom she had named years earlier when she first completed her account documentation. The firm's policies required written documentation before contacting a trusted contact, and once approval was confirmed, the compliance officer reached out to Mary's niece, who lived nearby. The niece had also noticed recent behavioral changes, including unpaid bills, missed appointments, and increased secrecy about finances. Together, the advisor and niece helped Mary realize that she was the target of a scheme designed to exploit her for financial gain.

Transitioning To Long-Term Support

Once the immediate threat was resolved, Evergreen moved into its post-intervention phase. The firm's Elder Client Review Committee met again to assess what had happened and to plan next steps. They documented the full timeline of events, noted how the internal procedures performed with respect to this specific situation, and identified opportunities for improvement.

Evergreen's first action was to strengthen Mary's financial oversight while preserving her independence. At the suggestion of the advisor and her niece, Mary agreed to add her niece as a co-trustee on her living trust account. The firm also worked with Mary's estate attorney to update her power of attorney and establish a backup fiduciary. These actions gave Mary confidence that she still had control but added an additional layer of protection against future exploitation.

The firm also increased the frequency of client check-ins. Instead of annual meetings, David scheduled quarterly calls with Mary and her niece. These conversations focused not just on investment performance but also on wellbeing – an approach consistent with Evergreen's philosophy of holistic financial care. During each call, David documented notes in the firm's CRM, capturing any behavioral observations or new requests that arose.

Evergreen's compliance department used this case as a training opportunity. They anonymized the details and presented it during the firm's annual Senior Safe Act training session. Employees discussed what worked well and what could have been improved. They noted that early documentation in the behavioral observation log had been critical in identifying the problem, and that prompt escalation through the 'Observe, Document, Escalate' model had ensured a swift and coordinated response.

The firm also recognized the value of cross-departmental communication. Because operations, compliance, and client service worked together seamlessly, critical details were thoroughly reviewed by subject matter experts. The review committee recommended periodic case simulations and refresher exercises to keep staff familiar with escalation protocols.

Building A Culture Of Continuous Vigilance

Evergreen's post-intervention review did not end with policy updates. The firm committed to embedding elder-client protection more deeply into its culture. Compliance added a senior-client monitoring review to its annual testing program, focusing on whether behavioral logs, trusted contacts, and transaction documentation were up to date. Operations created automated alerts in the CRM for clients over 75 to ensure advisors reconfirm trusted contact information during annual reviews.

Client education was also reinforced. The firm developed a short video for its client portal explaining common fraud tactics and how clients could protect themselves. Mary's experience, while anonymized, inspired a broader effort to raise awareness among all clients about the risks of financial exploitation.

A few months later, Evergreen received a thank-you letter from Mary's niece. She wrote, "Your firm's professionalism and compassion protected my aunt from losing her savings. She now feels secure again and knows she can trust your team." For the firm's employees, that letter validated all of the time spent refining procedures and training.

Lessons Learned

Mary's case reinforced several key lessons for Evergreen Advisory Partners and serves as a valuable roadmap for other advisors.

First, prevention depends on structure. Without formalized documentation and training, early warning signs could have been overlooked or dismissed as minor forgetfulness. The behavioral observation log gave advisors a simple yet powerful tool to identify changes before they escalated.

Second, intervention must be deliberate and consistent. Having a clear escalation pathway, authority to place holds, and coordination with custodians allowed the firm to act quickly without overstepping boundaries. Documentation created a defensible record that regulators would view as evidence of diligence and good faith.

Third, post-intervention processes are critical for long-term protection. The Elder Client Review Committee, incident logs, and periodic reviews turned a one-time crisis into an opportunity for improvement. Embedding lessons learned into training, policies, and culture ensured that future cases would be managed even more effectively.

Conclusion

As more clients face aging-related challenges, advisors play a critical pivotal in protecting them from poor decisions or financial exploitation. The best approach is to be proactive. Advisors should be aware of their legal responsibilities; adopt a well-conceived plan to prepare for, detect, and handle situations as they arise; and create protocols for effective communication to assure clients they are being cared for. By combining preparation, compassion, and clear procedures, advisors can better safeguard both their clients and their firms.

Leave a Reply